By Bonnie Yochelson

This essay first appeared as the introduction to Berenice Abbott: Changing New York, The Complete WPA Project by Bonnie Yochelson. ©1997 by the Museum of the City of New York. The perfectly gorgeous book contains the complete WPA project, every beautiful plate. We could only include a handful of them here, but the book itself is a treasure trove worth seeking.

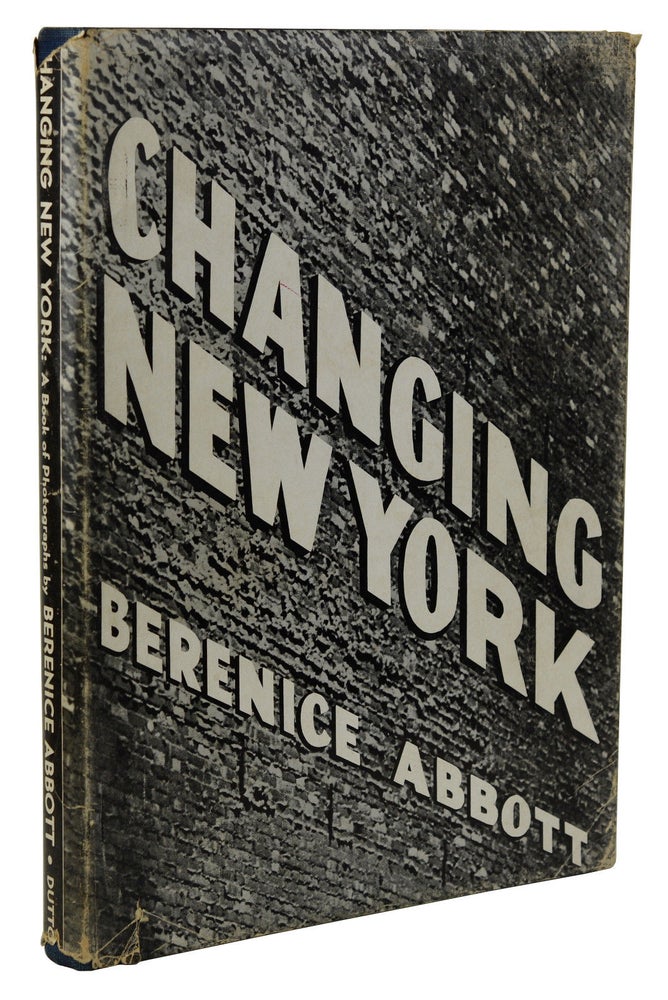

In January 1929, after eight years in Europe, thirty-year-old Berenice Abbott returned to the United States for what was planned as a short visit. When she arrived, she was seized by a “fantastic passion” to photograph New York City, a passion she pursued against great odds for the next decade. The resulting Changing New York project, funded by the Federal Art Project and sponsored by the Museum of the City of New York, contains 305 photographs supported by historical data compiled by her staff of researchers. In April 1939, E.P. Dutton & Co. published Changing New York, a guidebook aimed at visitors to the New York World’s Fair, which included ninety-seven of Abbott’s photographs with captions written by Elizabeth McCausland, an esteemed art critic and Abbott’s companion.

In February 1940, the monthly magazine Popular Photography asked Abbott to name her “favorite picture.” She balked at the question but responded:

Suppose we took a thousand negatives and made a gigantic montage; a myriad-faceted picture combining the elegances, the squalor, the curiosities, the monuments, the sad faces, the triumphant faces, the power, the irony, the strength, the decay, the past, the present, the future of a city — that would be my favorite picture.1

Although not a montage from 1,000 negatives, this book, for the first time, presents all of Changing New York: all 305 photographs and the story of how Abbott’s “fantastic passion” became a New Deal art project.

Abbott belonged to what Gertrude Stein labeled “the lost generation” of Americans who came of age during World War I and rejected parental expectations to pursue a life of art. Burn July 17, 1898, in Springfield, Ohio, “Bernice” spent an unhappy childhood with her divorced mother, separated from her father and her five siblings. In an autobiographical sketch, she told of her “first act of rebellion”:

The day after I graduated from Lincoln High School in Cleveland, Ohio, I had the barber cut off the long, thick braid which hung down my back…and with its departure came a great sense of relief. I felt lighter and freer … Shortly thereafter I arrived at Ohio State University in Columbus … My bobbed hair startled the campus. A handful of students from New York at once mistook me for a “sophisticate,” a wordly New Yorker. All this because of my short hair. We became friends, and a new life began for me.2

Abbott left Ohio State in early 1918 to follow her new friends James Light and Susan Jenkins to New York, which Malcolm Cowley, another new friend, later called “the homeland of the uprooted.”3 Sharing a room on MacDougal Street with Light and Jenkins, who had joined the Provincetown Players, Abbott landed in the heart of Greenwich Village bohemia. As “the youngest thing around,” she played bit parts in Eugene O’Neill plays and was adopted as “the daughter” of Hippolyte Havel,4 a legendary anarchist best remembered for declaring Greenwich Village “a spiritual zone of mind.”5 In the winter of 1919, Abbott almost died of the virulent influenza that took the lives of 12,000 New Yorkers. Upon her recovery, she moved out of the apartment she had shared with Light, Jenkins, and writers Cowley, Kenneth Burke, and Djuna Barnes, later claiming that their crowd was “too bohemian.” Abandoning her desire to be a writer, Abbott took up sculpture and supported herself with odd jobs. By 1920, she had befriended Dadaists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, whom she boasted of having taught to dance.

The economic boom and political repression following the war changed the temper of Greenwich Village life. As a national symbol of rebellion, the Village attracted tourists who came to gawk at its bohemian “characters” and, with the passage of the Volstead Act, to drink in its many illegal speakeasies. Real estate speculators and entrepreneurs followed, alienating aspiring artists like Abbott, who had come to the neighborhood to escape America’s increasing commercialism. The exodus to Paris soon began and, in the spring of 1921, Abbott joined it.

Abbott was inspired by the “memories, accounts, and fantasies” of the Baroness Else von Freitag-Loringhoven, a wildly extravagant Village personality whose poetry Abbot greatly admired. She carried with her the baroness’s florid letter of introduction to Andre Gide, with whom she became friends, and with the help of sculptor John Storrs, rented a picturesque studio on the Left Bank. In Paris, Abbott adopted the French spelling “Berenice” and found what she later called a “hotbed of artistic production and theory” centered as much in cafés as ateliers.6 In 1923, wanderlust led Abbott to Berlin, where hyperinflation allowed expatriate artists to subsist on meager amounts of foreign currency. When a promised twelve-dollar weekly stipend from an American patron did not materialize, she was devastated. Having sublet her Paris apartment to American tourists, she returned there, homeless and penniless.

A chance meeting with Man Ray, who had also moved to Paris in 1921, set the course of Abbott’s future. Man Ray’s portrait studio in Montparnasse was thriving, but he complained bitterly that his darkroom assistant refused to follow instructions. He was seeking a replacement “who knew nothing of photography.” Abbott met that qualification, and the next morning she began the first steady job of her life, at a salary of ten francs (less than two dollars) a day. At first, her desire to succeed was based on her desperate financial need, but she quickly found that she loved the work. Her training in drawing and sculpture lent her prints a sensitivity to volume. Man Ray was impressed, too, and soon raised her salary to twenty-five francs a day. Abbott stayed with him for more than two years: “I slaved for Man Ray, but I was glad to do it. I was very glad to have the experience.”7

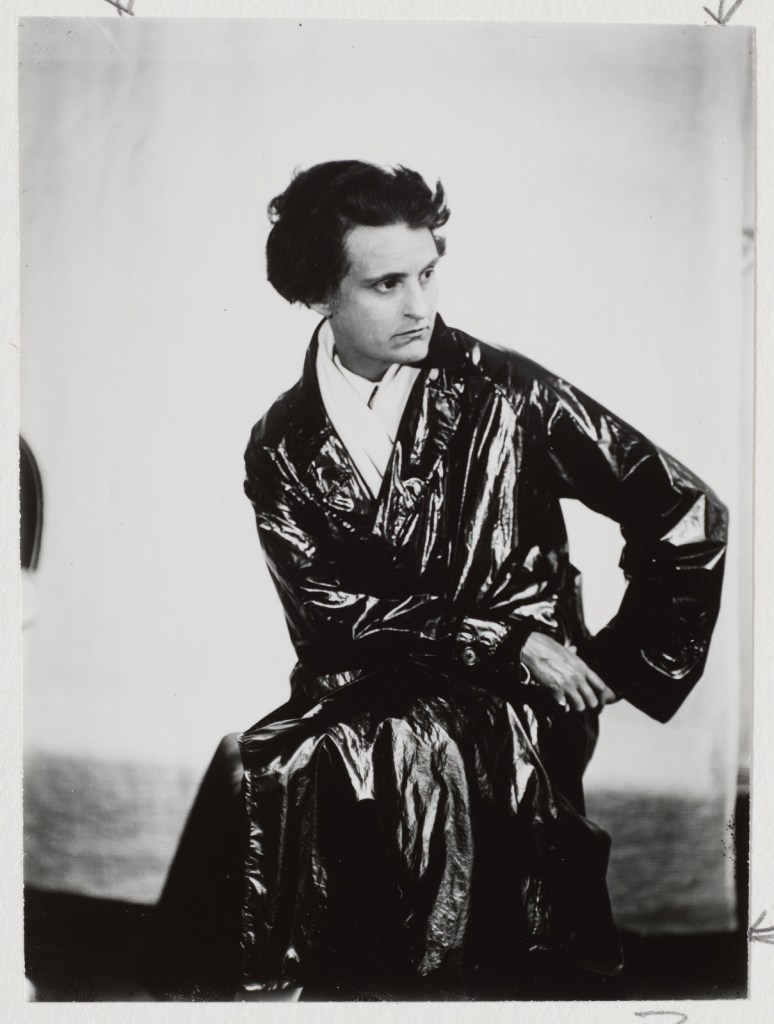

Instead of increasing her salary further, Man Ray offered Abbott his studio to make her own portraits, and soon her reputation rivaled his. Their styles differed — Man Ray excelled at stylization and abstract composition, while Abbott sought naturalness and spontaneity — and many sitters who hired Man Ray wished to pose for Abbott as well. “To be ‘done’ by Man Ray or Berenice Abbott meant that you rated as somebody,” remarked Sylvia Beach, proprietor of the avant-garde bookstore Shakespeare & Co. (fig.1).8 Jean Cocteau, Janet Flanner, Jules Romain, James Joyce, and Peggy Guggenheim were among those “done” by Abbott. In 1926, after a well-received one-person exhibition at a small Parisian art gallery, Abbott opened her own studio, continued to build her clientele, and sold portraits to French Vogue and avant-garde magazines. As many American writers and artists were lured back to New York’s burgeoning publishing and advertising industries, Abbott stayed on, enjoying her first taste of financial security and professional stature.

Abbott’s success as a photographer was due largely to her natural talent and technical finesse. By playing an important role in the lively critical debate on photography and modern art, she forged her own artistic philosophy and enhanced her stature within the international avant-garde community. She joined the modernist attack on pictorialism, the soft-focus style of landscapes and domestic genre scenes, which by the 1920s was artistically exhausted but still favored by photographic organizations worldwide.

The dispute between pictorialists and modernists concerned style and content: Abbott and her colleagues believed that soft-focus compromised the inherent clarity of the photographic image and that pictorial subject matter amounted to escapism, a denial of modern urban life. In May 1928, the Premier Salon Indépendant de la Photographie opened on the staircase of the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées to protest the established Salon de la Photographie. The Salon de l’Escalier, as it was nicknamed, featured a varied group of photographers, including Abbott, Man Ray, photojournalist Germaine Krull, street photographer Anaré Kertész, and Vogue photographers Paul Outerbridge and George Hoyningen-Huene. In the words of organizer Florent Fels, “All took care to be exact, clean, precise.”9

Modernists also recast the old pictorialist debate about the artistic status of photography. The mechanical nature of the medium, long considered a liability, became an asset. Inspired by art patron Leo Stein, who advised her that “essentially ours is a scientific age,” 10 Abbott embraced photography’s new-found prestige, confident that the medium was ideally suited to the twentieth century “with its stepped-up tempo and new demands on awareness. “11

Among modernists, two conflicting approaches to photography emerged. In September 1928, Pierre MacOrlan, a mystery writer and Abbott’s friend, defined the approaches as “plastic” and “documentary.”12 “Plastic” photography referred to mechanical experiments, such as photograms or compositional experiments with abstraction and distortion that were derived from painting. By contrast, documentary photography relied less on technique than on vision, capturing “contemporary life … at the right moment by an author capable of grasping that moment.” For MacOrlan, documentary photography was “the most accomplished art, capable of realizing the fantastic and all that is curiously inhuman in the atmosphere that surrounds us, and even in man’s very personality.” Because photography enabled an artist to reveal the fragmented, disorienting experience of the modern city, it qualified as “the expressionist art of the era.” 13

Advocates of documentary photography searched the medium’s obscure history and found two worthy ancestors: Nadar, whose Second Empire portrait studio still operated under his son’s management, and Eugène Atget, who documented Paris from the 1880s until his death in 1927. Both Nadar and Atget were shown at the Salon de l’Escalier, and thanks to Abbott’s efforts, Atget’s photographs appeared continually between 1928 and 1930 in international avant-garde exhibitions and publications, most notably the 1929 Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart.

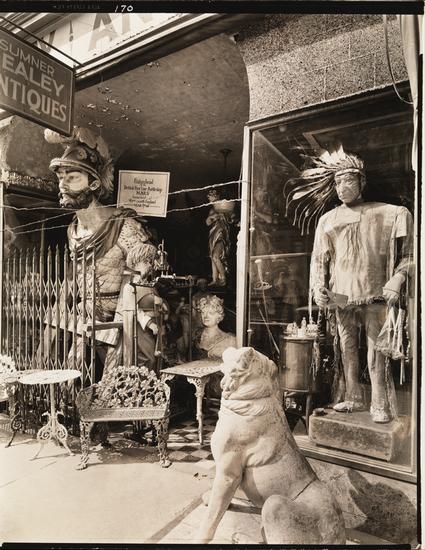

Abbott learned of Atget from Man Ray, who had discovered the elderly photographer’s studio on the same street as his own. Man Ray and his surrealist friends found in Atget’s images of deserted streets, storefronts, and service vehicles a feeling for the mystery lurking just beneath the surface of ordinary experience. Among Atget enthusiasts, Abbott was the most fervent. She visited him, purchased his photographs, and persuaded him to come to her studio to pose for a portrait. In August 1927, when she brought the prints from the sitting to his studio, she discovered that he had died. Fearing that his work would be lost, she sought out Atget’s executor and, with financial help from friends, purchased his 1,400 glass plate negatives and 7,800 prints. In 1930, she arranged for the publication of a book of Atget’s photographs with an introduction by MacOrlan. Until 1968, when she sold the Atget Collection to the Museum of Modern Art, Abbott worked tirelessly to cement Atget’s reputation as a precursor of modern photography.

Why would a young artist of limited means make such a commitment? Abbott later remarked that “Atget’s photographs … somehow spelled photography for me.” Recalling the first time she saw his photographs, she wrote:

Their impact was immediate and tremendous. There was a sudden flash of recognition — the shock of realism unadorned. The subjects were not sensational, but nevertheless shocking in their very familiarity. The real world, seen with wonderment and surprise, was mirrored in each print. Whatever means Atget used to project the image did not intrude between subject and observer. 14

Abbott learned other essential lessons from Atget’s career. Although he earned his living selling prints to whoever found them useful — artists, antiquarians, and craftsmen — Atget had shunned commissions because, as he told Abbott, “people did not know what to photograph.” Instead, he chose “an immense subject,” “creat[ing] a collection of all that which both in Paris and its surroundings was artistic and picturesque.”15 Moreover, Atget worked alone, pursuing his epic task without benefit of a comfortable income, an audience, or a nurturing artistic community. Meeting Atget at the end of his career and the start of her own, Abbott found in him a true mentor.

In January 1929, Abbott sailed to New York to locate an American publisher for her Atget book and found her own “immense subject.”

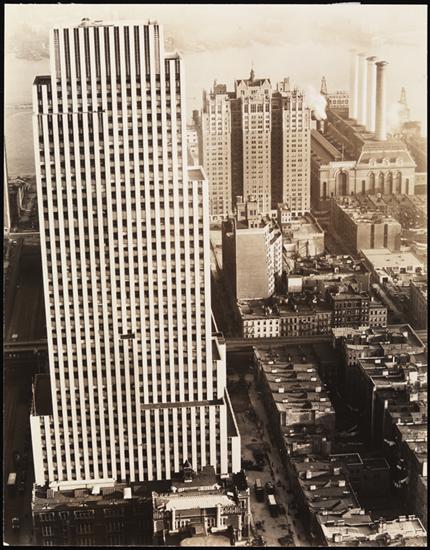

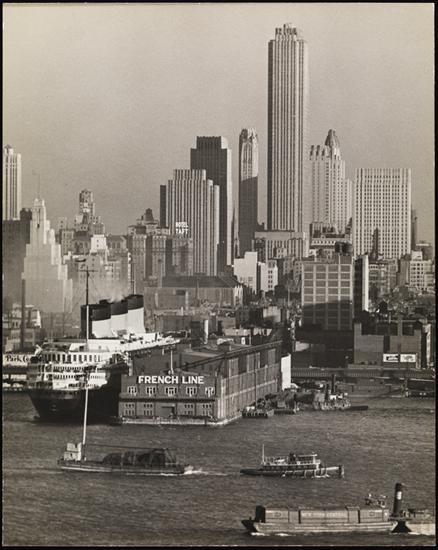

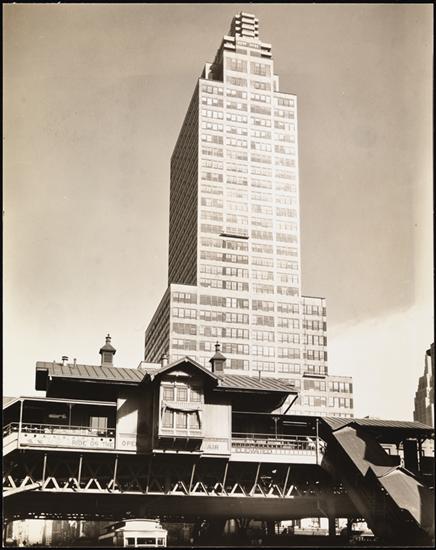

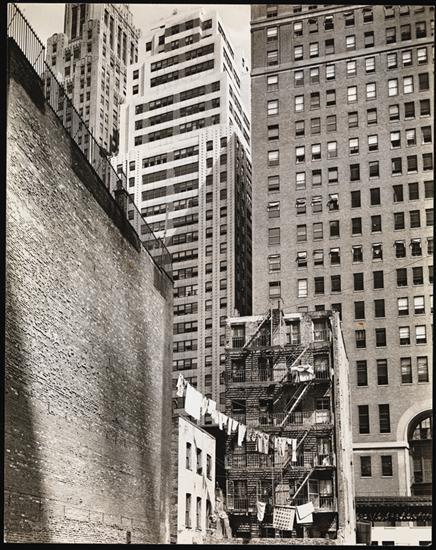

DURING ABBOTT’S ABSENCE, NEW YORK experienced its second great skyscraper building boom. The cathedrals of commerce, which had transformed Manhattan’s skyline into what Henry James in 1904 had disparagingly called “extravagant pins in a cushion,” were dwarfed by new 1,000-foot towers, which crowded the narrow streets of the financial district and fanned out from Grand Central Terminal in midtown. To the usual noise and dirt of the elevated trains and street traffic was added the tumult of construction, as hundreds of nineteenth-century buildings fell, and cranes carried steel girders, brick, and stone aloft by the ton. A new skyscraper form — with a bulky base, setback tower, and a sleek, Art Deco skin — replaced the turn-of-the-century model, a classical column encrusted with a hodge-podge of historical ornament.

Abbott was swept off her feet: “The new things that had cropped up in eight years, the sights of the city, the human gesture here sent me mad with joy and I decided to come back to America for good.” 16 Within weeks she had leased a studio, and after visiting her mother in Cleveland — and looking up Margaret Bourke-White, whose industrial photographs she admired — she returned to Paris, sold her furniture, and packed up the Atget collection, which filled twenty crates.

Although the decision to return permanently was spontaneous, Abbott’s yearning for America had been growing for several years. From afar, she had read avidly about the astounding growth of America into a world power. A 1927 book America Comes of Age by French economist André Siegfried, helped her decide to come home. After traveling six months throughout the states, Siegfried concluded that America’s material advances were great but its sacrifice of individual expression was greater: “Modern America has no national art and does not even feel the need of one.”17 Like many artists of her generation, Abbott had fled America precisely because of its materialism. Having established herself as an artist on foreign soil, she returned home to help create an American art. Three months before her 1929 trip, Abbott told a reporter from Cleveland that she intended to move back to Ohio and “come over to France every couple of years or so for a visit.” Noting that she was “thoroughly American,” she explained her evolving emotions: “When I came over seven years ago I loathed America; I ran away from it. But I guess those who rebel most against it love it the most.”18

Once home, Abbott sensed her advantage as a returned expatriate:

I am an American, who, after eight years’ residence in Europe, come back to view America with new eyes. I have just realized America — its extraordinary potentialities, its size, its youth, its unlimited material for the photographic art, its state of flux particularly as applying to the city of New York … I feel keenly the neglect of American material by American artists … America to be interpreted honestly must be approached with love void of sentimentality, and not solely with criticism and irony.19

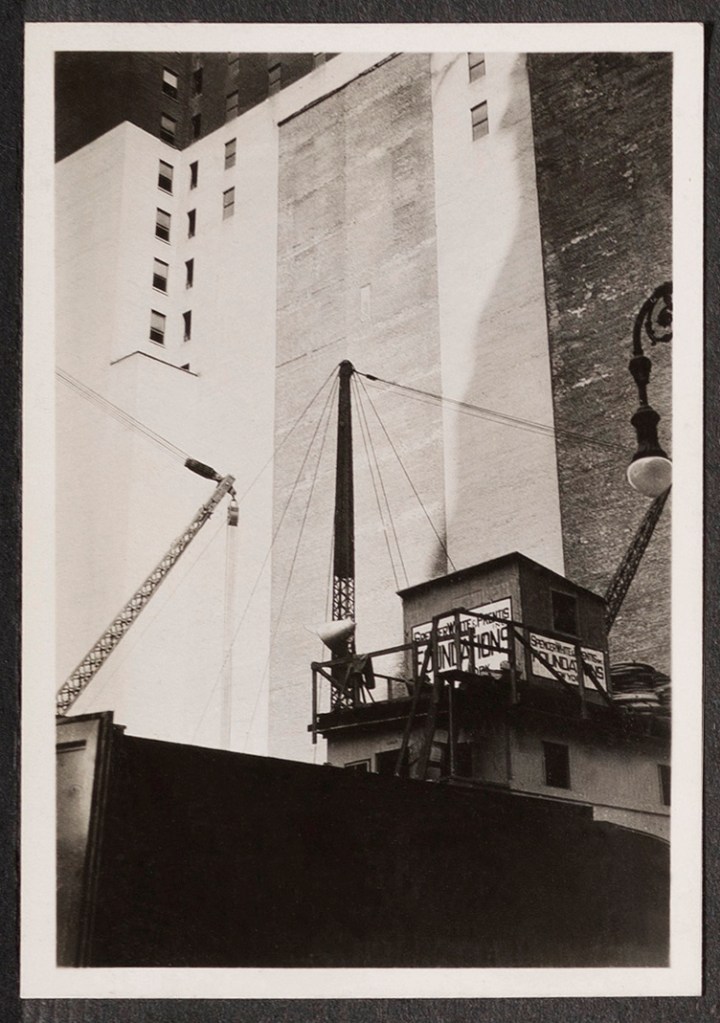

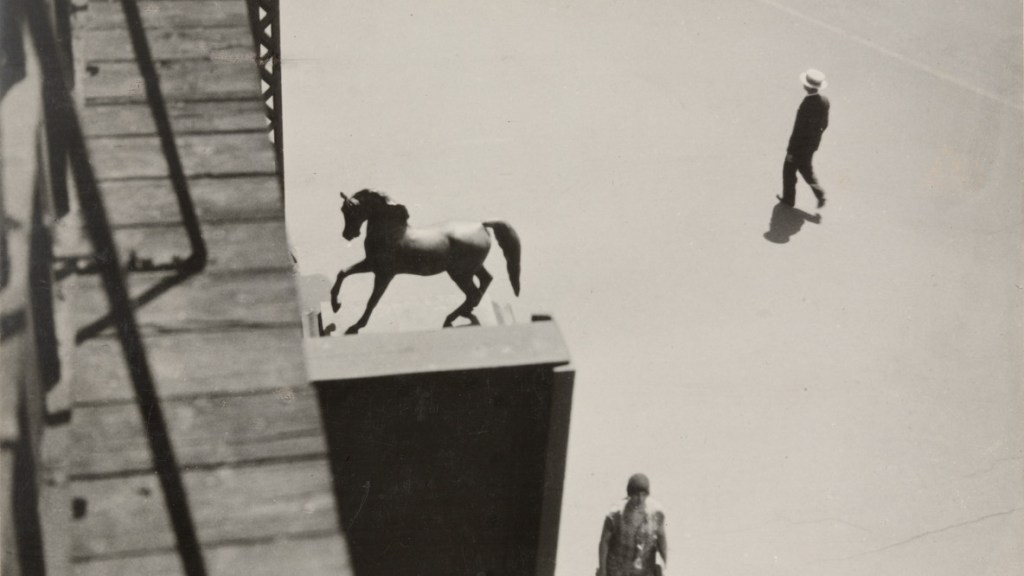

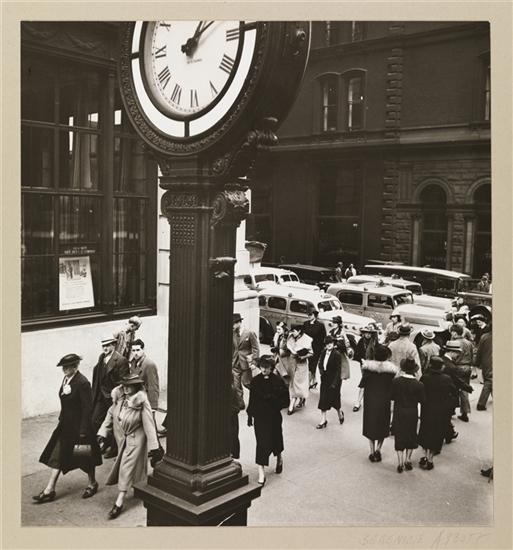

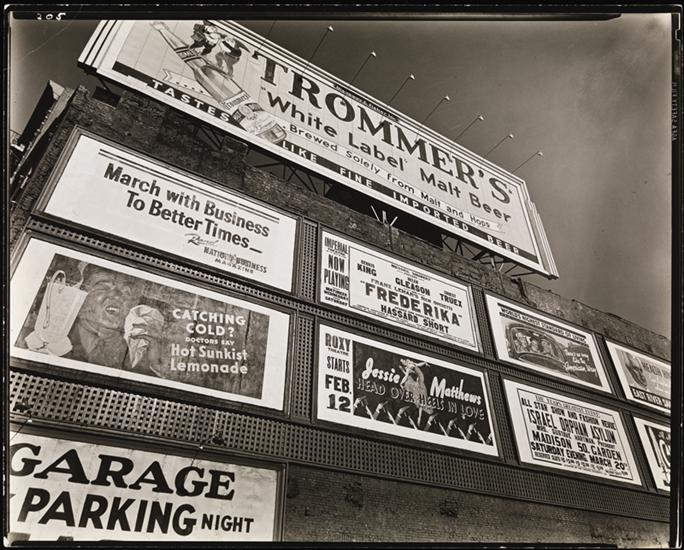

Although she immediately sensed her goal, Abbott’s vision evolved more slowly. During 1929, she made over 200 negatives with a hand-held camera and compiled a scrapbook containing contact prints of most of them.20 She called these photographs “just notes,” the beginnings of ideas for later development, and she revisited some themes, such as skyscrapers, elevated trains, and street peddlers, in later years. Many of these early New York photographs — especially the twenty she enlarged for various exhibitions and publications — were more than quick studies and differ substantially from her later work. The best reveal the influence of European aesthetics. Building New York (fig. 2), for example, applies the lessons of cubist construction to the actual construction of a skyscraper, transforming the tumult of a specific time and place into a celebratory symbol of the machine age. In Lincoln Square (fig. 3), Abbott again eliminated particularities, this time to capture the disorienting sensations of city life that had been described by MacOrlan and the surrealists. Taken from the platform of the Ninth Avenue El, the photograph skillfully suggests that persons and objects are interchangeable, and that movement is constant but without apparent purpose.

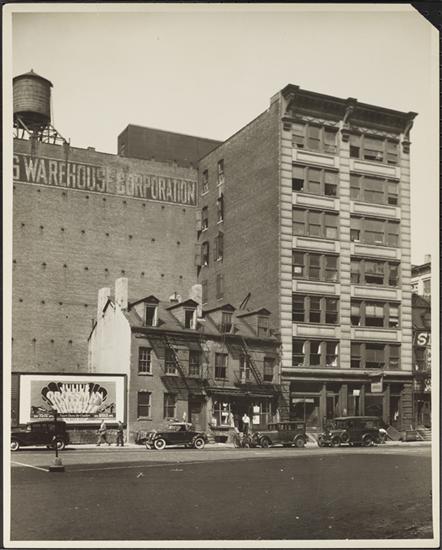

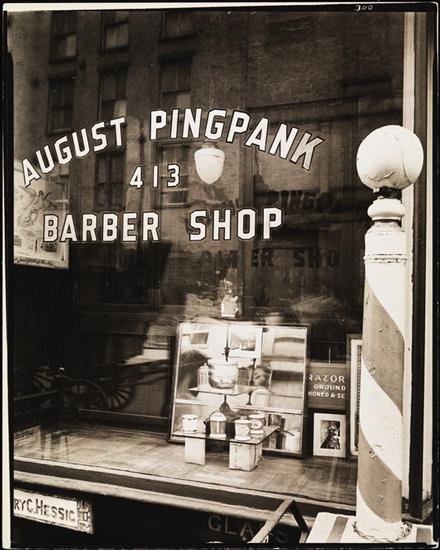

In 1930, Abbott purchased an 8 x 10-inch view camera, which radically changed her style and themes. A comparison of two Lower East Side street scenes — Hester Street (fig. 4), taken with the handheld camera, and Cherry Street (fig. 5), an early attempt with the view-camera — illustrates the change. Hester Street arrests movement, with pedestrians moving left, right, and toward Abbott, as she pointed her camera down the sidewalk. Like surrealist mannequins, the garments, hung out as advertisements, suggest surrogates for the living. Cherry Street, which shows the plain facades of a group of the city’s oldest buildings, is static by comparison. Although the women and children on the central stoop add human interest, they are remote; architecture is the principal subject.

Abbott sacrificed the speed and flexibility of the small camera, which had allowed her to stop action close-up and to work quickly without drawing attention to herself, for the added detail and control of the large camera, which required her to use a tripod and duck her head beneath a focusing cloth. Under the cloth, Abbott saw the exact image full size, albeit upside down. Rather than sacrifice definition through enlargement, she contact-printed the 8 x 10-inch negative, retaining maximum detail. With the new camera came a shift in subject matter: Instead of concentrating solely on subjects that symbolized the speed and brashness of American life — skyscrapers, immigrant neighborhoods, and mass transit-she found subjects that were disappearing in the wake of accelerated change.

Abbott took up the view camera as she was cleaning and printing Atget’s 8 x 10-inch glass negatives, and preparing the book Atget, photographe de Paris for publication. Her decision to use his type of camera and to turn to historical subjects surely reflects the influence of his example. To more than one reporter she mentioned her aim to “do in Manhattan what Atget did in Paris.”

In 1930, for a German publication on early photography, Abbott also began researching the Civil War photographs of Mathew Brady.21 She was inspired by Brady’s determination to create a photographic record of a turning point in American history, and saw in Brady’s primitive technique and “artless” style a means of escape from modernist sophistication.22 With the view camera, Abbott sought to emulate the simplicity of Atget and Brady.

Although “[her] friends thought [she) was crazy” to give up her Paris-based business and reputation, Abbott was confident she could succeed in New York. Intending to support herself through portraiture, she rented an expensive studio in the luxurious Hotel des Artistes off Central Park at West 67th Street. Shortly after settling in, her prospects dimmed. Fashionable Americans, she learned, were unaccustomed to spending $50 for a portrait photograph, and their expendable income was fast dwindling. Through the recommendation of Bourke-White, she was hired by Fortune magazine to photograph corporate executives, but Abbott found her subjects disagreeably vain and insecure. In 1932, she was forced to vacate her expensive studio and moved twice that year.

Despite financial difficulties, Abbott gained recognition as an artist and an art-world celebrity. The stylish young woman from Paris who had photographed Europe’s cultural elite warranted several feature stories in newspapers and magazines. She kept her distance from Alfred Stieglitz, the éminence grise of American photography who held court in his tiny midtown gallery, but found support from a group of young Harvard alumni — especially Lincoln Kirstein and Julien Levy — who avidly patronized modern art. In November 1930, her works appeared in an exhibition at the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, organized by Kirstein and modeled on the 1929 Film und Foto show. In 1932, her photographs were included in two similar exhibitions at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo and the Brooklyn Museum. That same year, she contributed a photomural to an exhibition that Kirstein and Levy organized for the fledgling Museum of Modern Art. Inspired by the Mexican muralists, Kirstein had invited more than fifty artists to design murals on “the post-war world.” Only three weeks before the opening, Levy invited a dozen photographers to demonstrate “what the photograph can present that is not better rendered in paint.” Abbott submitted New York (fig. 6), a photomontage measuring 7 x 12 feet, with fragments of New York scenes inserted between giant girders.

In 1930, the financial strain of publicizing the Atget collection led Abbott to sell a share to Levy, who opened a New York gallery devoted to photography. In May 1932, Levy included Abbott in Photographs of New York by New York Photographers, and in September, he presented her first one-person New York show. It was well-reviewed but achieved no sales. Soon Levy abandoned the unprofitable field of photography for painting and sculpture.

Abbott’s scramble for work left her little time and less money to photograph New York. Traveling throughout the city, she took note of potential photographic subjects but could afford to devote only one day a week for her project. Each Wednesday, she hoped that good weather and the occasional loan of a car would result in a productive outing. Soon realizing she would accomplish little without full-time support, she applied to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which in 1925 had originated the idea of subsidizing young scholars and artists for a year. Her application to “mak[e] a documentary interpretation of New York City in photographs” was denied in 1932, however, and again in 1934.

Abbott also approached the Museum of the City of New York for support. Founded in 1923 and modeled on Paris’s Musée Carnavalet, the Museum was the first American institution devoted to documenting a city’s history. Like John D. Rockefeller’s restoration of historic Williamsburg and Henry Ford’s assemblage of Greenfield Village, it sought to nurture the growing appreciation of early American culture — what critic Van Wyck Brooks had famously described as the search for a “usable past.” Unlike Williamsburg or Greenfield Village, however, the Museum faced the pressing need to salvage the remnants of a past urgently threatened by an unprecedented building boom. From the Museum’s inception, its founders sought to preserve a comprehensive pictorial record of the city’s evolving appearance, and, as early as 1924, they had discussed the idea of photographing every city street.23

When in November 1931, Abbott wrote the Museum’s director, Hardinge Scholle, she wisely emphasized the historical nature of her plan and enlisted the Museum’s aid in “designating interesting landmarks bearing on the development and nature of the city that are about to be destroyed.”24

The same week she met Scholle, Abbott visited I. N. Phelps Stokes, the scion of an old New York family and a distinguished architect, historian, and housing reformer. Stokes’s six-volume Iconography of Manhattan Island (1915-1928) was drawn largely from his own authoritative collection of historical prints. As Scholle’s informal adviser, Stokes enthusiastically endorsed Abbott’s project. Her proposal recalled his own plan, never realized, “of zigzagging through all the streets and avenues of the city, from the Battery to Spuyten Duyvil … making snapshots of the most interesting landmarks.” In his enthusiasm, Stokes revised Abbott’s working method, substituting a two-part collaborative plan for Abbott’s intuitive approach. In the first stage, Abbott would “visit systematically, by motor, every street on Manhattan Island,” making snapshots and notes; in the second stage, she would select “in consultation perhaps with [Scholle] and me, or a Committee appointed by the Museum” 500 to 1,000 sites to rephotograph with a large camera.25

Scholle was impressed with Abbott’s photographs and noted that he “ha[d] always felt work this sort should be undertaken by our Museum as soon as finances permitted.”26 Unfortunately, funds were not available, as the Museum struggled to complete its new building at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street in the worst days of the Depression. Scholle, however, helped Abbott in numerous small ways. Stokes had proposed as a fundraising event that a selection of Atget’s photographs hang with Abbott’s work in the Museum’s inaugural exhibition, which was then in the planning stages. The January 1932 exhibition included four of Abbott’s prints, without the Atgets. In February, Scholle helped Abbott gain access to the Rockefeller Center construction site, where she made some of her most powerful and historically significant photographs. In March, he referred her to the owner of a collection of New York nineteenth-century negatives, who sought an expert printer, and, in September, he sent notices of Abbott’s Levy gallery exhibition to potential supporters. Scholle’s moral support was heartening, but Abbott continued to look elsewhere for funding. In December 1932, she solicited the venerable New York Historical Society, whose board of trustees politely turned her down.27 Anne Morgan, J. P. Morgan’s daughter and a portrait client, offered her $2,500 if she could match it, which she could not.

The relentless flow of negative responses confused Abbott. Her requests varied widely from the minimum amount needed to the ideal. When Abbott first approached Scholle, she asked him for $4,200 to cover one-year’s salary and photographic materials. She asked Stokes for $5,000, but immediately revised the sum to $10,000. And in her letter to the New York Historical Society, she asked for $19,500, including the cost of a car and salaries for two assistants.

In June 1933, Abbott made her last and most ambitious fundraising effort. Supplied by the Museum with the names and addresses of one hundred prominent New Yorkers, Abbott sought seventy-five patrons to contribute $250 each for a total of $15,000. Accompanying Abbott’s proposal were letters of support from Scholle and architect Philip Johnson, a friend of Kirstein’s and Chairman of the Department of Architecture at the Museum of Modern Art. Abbott’s reward for this herculean typing task was a large stack of rejection letters. Some were quite memorable: Wall Street lawyer Samuel Untermyer, for example, declined support, noting that “with a large part of the population of this City almost starving, … projects of th[is] kind can await more auspicious times.”28

Abbott not only failed to raise money, but also succeeded in incurring the wrath of one of the Museum of the City of New York’s most valued patrons, realtor J. Clarence Davies, who had founded the Museum’s Print Department with a gift of 15,000 prints, maps, drawings, and photographs. A month before receiving Abbott’s letter, Davies had donated to the Museum a group of specially commissioned photographs of buildings likely to be soon demolished. For the project, he had hired Charles Von Urban, a competent professional photographer, to document every wood-frame building on Manhattan Island. Unable to distinguish his project from Abbott’s, Davies expressed dismay: “Considering the fact that I have spent a good deal of time and money in contributing to the Museum some six hundred photographs of the kind referred to in these letters, of course I would be unwilling to go further.”29 To appease him, the Museum in December 1933 presented a small exhibition of Davies’ gift, which was called Vanishing New York. The aesthetic difference between Von Urban’s serviceable record photograph of 512-514 Broome Street and Abbott’s carefully structured composition of the same site, made in 1935, was of no consequence to Davies (fig. 7 and Greenwich Village Plate 1).

Having failed to raise money to photograph the city, Abbott accepted other work. In the fall of 1933, she began teaching the first photography course given by the New School for Social Research. Founded in 1919 in Greenwich Village, the New School offered a progressive alternative to traditional college education, employing part-time lecturers, offering non-credit evening courses, and fostering interdisciplinary studies. Its arts faculty, which included composer Aaron Copland, dancer Doris Humphrey, painter Stuart Davis, architectural historian Lewis Mumford, and Abbott’s friend Leo Stein, was particularly strong. At first terrified of teaching, Abbott remained on the New School faculty until 1958.

In the summer of 1934, Abbott spent six weeks with architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock, making photographs for two Hitchcock projects: an exhibition on the Victorian architect H. Н. Richardson for the Museum of Modern Art and an exhibition on pre-Civil War American architecture for Wesleyan University, where Hitchcock taught. Their travels took them to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston. Hitchcock belonged to the Harvard group closely associated with the Museum of Modern Art; in 1932, he and Philip Johnson had organized a groundbreaking exhibition on what they named “the international style” of modern architecture. Hitchcock’s historical studies were colored by his modernist aesthetics. In Richardson, he saw a protomodernist, and in early nineteenth-century architecture he identified a functional style unencumbered by the false pretensions of Victorian academic architects. The simple buildings of America’s oldest cities represented “a truly American urban vernacular”30 and provided a “usable past” for the modern architect.

The Wesleyan exhibition on pre-Civil War architecture proved an especially rewarding collaboration of author and illustrator. Working beside Hitchcock, Abbott sharpened her eye for early American architecture and practiced the stylistic restraint required of a commission. Her style — direct, selfless, and functional — perfectly fit Hitchcock’s subject. That Hitchcock included Cherry Street, taken in 1930, in the exhibition demonstrates that Abbott had been exploring this aesthetic in her independent work. Writing in 1939, Hitchcock acknowledged his debt: The photographer may well be so important a collaborator that, when the work is completed, the original initiator must… recogniz[e] that the quality of the achievement is ultimately wholly due to the photographs.31

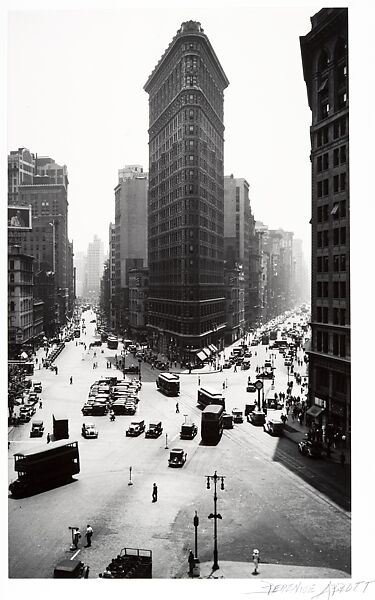

In 1934, Abbott found several outlets for her New York photographs. In March, her close friend Marchel Landgren arranged a solo exhibition at the New School. Later that year, she was well-represented in This Is New York, a stylish, guidebook claiming to be “the first modern photographic book of New York.”32 In his introduction, Gilbert Seldes, an early defender of American popular culture, explained that the book enlisted “the artists of photography” to show its readers “how to see” New York. Abbott’s photographs matched Seldes’s point of view: “The pictures have been selected and arranged to show New York as it is, without, we hope, any false glamour; the true glamour being sufficient.” Featuring one or two photographs by Ralph Steiner, Margaret Bourke-White, Walker Evans, Thurman Rotan, Anton Bruehl, and Wendell MacCrae, it included twelve by Abbott. Although most of her photographs depicted landmarks, such as the Stock Exchange and the Flatiron Building, the book also reproduced her now-famous Midtown Night View, taken from the top of the Empire State Building.33

On October 8, 1934, Abbott’s first one-person museum exhibition, New York Photographs by Berenice Abbott, opened at the Museum of the City of New York. In its third year on Fifth Avenue, the Museum was operating smoothly. Grace Mayer, a young, self-taught, and intuitively gifted curator, was responsible for the small special exhibitions gallery on the main floor, where Abbott’s prints were hung. In 1934, Mayer mounted six shows covering a wide variety of themes, from a pictorial history of Central Park to drawings by the popular illustrator Vernon Howe Bailey. Abbott’s was not the Museum’s first one-person photography exhibition; in March 1934, it had presented New York Night Scenes, twenty-two photographs by Samuel Gottscho, an architectural photographer who had been commissioned to photograph the Museum’s new building. For the Abbott exhibition, Scholle personally guided tours for wealthy New Yorkers, still hoping to find a patron to subsidize Abbott’s larger ambitions. No patron was found, but the show proved extremely popular and was extended from November to February 1935.

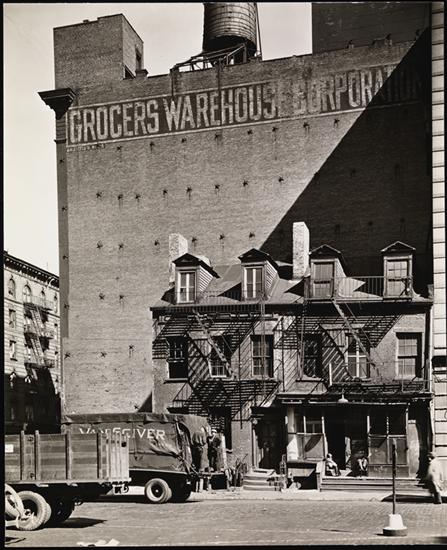

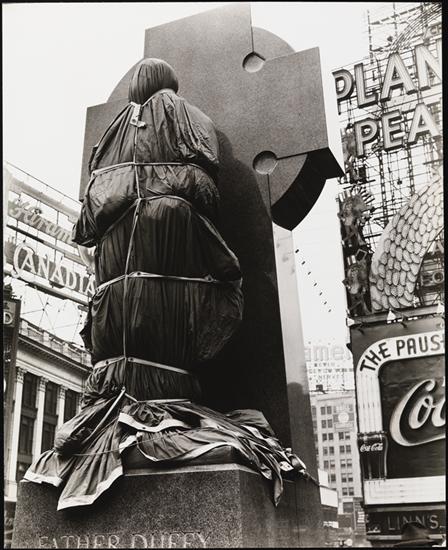

Of the forty-six prints in the Museum’s exhibition, very few depicted landmarks, and only six of Seldes’s selection were included. The show departed from the standard presentation of photographs as individual works of art: twenty were individually mounted; shop fronts were shown two per mount; Lower East Side street scenes were shown three per mount; and six Rockefeller Center construction scenes were mounted together. Learning from her Museum of Modern Art photomural experience, Abbott experimented with scale, displaying a 4-foot by 11-inch enlargement of Exchange Place, which a New York Times reviewer called “rather terrifying.” Original photographs were used to make museum posters; one showed a statue of Puck, the namesake of the celebrated Victorian magazine (fig. 8).

The exhibition received positive notices in the New York Times and the New York Sun, and the Herald Tribune ran a double-page spread with six large reproductions. Writing for The New Yorker, Lewis Mumford, who had reviewed Abbott’s 1932 show at Julien Levy, “wished for miles and miles of such pictures, with even more emphasis on the human side.” Throughout the 1930s, Abbott defended the relative unimportance of people in her street scenes, especially in comparison with popular paintings of the period. One critic, however, found relief in her photographs, preferring them to the crowded canvases of Kenneth Hayes Miller or Reginald Marsh: Here indeed is the American Scene more authentically recorded than it has ever been by that school of painters whose tiresome formula is: Fourteenth Street + Italian Renaissance technique = American Art.34

The most penetrating review of Abbott’s show came not from a New Yorker but from Elizabeth McCausland, art critic for the liberal Massachusetts newspaper, the Springfield Republican. The review marked a turning point in the lives of both artist and critic. Born in 1899 in Wichita, Kansas, McCausland became a reporter for the Republican in 1923, three years after graduating from Smith College. She was an idealist in art and politics, devoted to American poetry, modern art, and social activism. In the 1920s, she had reported sympathetically on Sacco and Vanzetti, the New Bedford textile strike, and child labor reform. When she began writing art criticism in the 1930s, McCausland favorably reviewed Alfred Stieglitz’s artists, explaining the goals of abstraction and straight photography to her New England audience. As the Depression deepened, her artistic and political concerns merged: She espoused social realism and encouraged artists to balance political commentary and personal expression.

In Abbott’s photographs, McCausland saw the fulfillment of this ideal. Praising Abbott for choosing “a big theme and approach[ing] it modestly,” McCausland believed that Abbott’s “realistic and objective approach to the city … succeed[ed] in creating the spirit of the city.” The central paradox of Abbott’s art — that her restraint enhanced her expressiveness — was, for McCausland, the “hope of art in any age, not only of American art in 1934.”35

McCausland sent Abbott the review, and Abbott responded that she considered the article “the first intelligent one on my work that has appeared in this country.” “To put it mildly,” Abbott wrote, “I have and have had a fantastic passion for New York, photographically speaking.”36 McCausland promptly wrote back:

I’m glad you have a fantastic passion for New York … and probably it was some intuition of that passion which made me write as I did of your work. For only from passion and fantastic passion does any sense of reality in art, or in life, come, I think.

McCausland teased Abbott, using the word “passion” eleven times in the letter and noting her own “fantastic passion for AMERICA,” including such provincial oddities as the county courthouse in Bolivar, Missouri, and “some funny facades in Troy, N.Y.”37 The exchange of letters initiated Abbott and McCausland’s thirty-year partnership.

The two women were formally introduced by Marchel Landgren, who asked McCausland to write on Abbott for the arts magazine Trend, which he edited. The Trend article of March 1935 recast Abbott in McCausland’s image. The effects of Abbott’s Parisian experience were described as “probably a somewhat artificial European esthetic imposed on her natural sturdiness and integrity.” And Abbott’s “fantastic passion” was invested with political meaning:

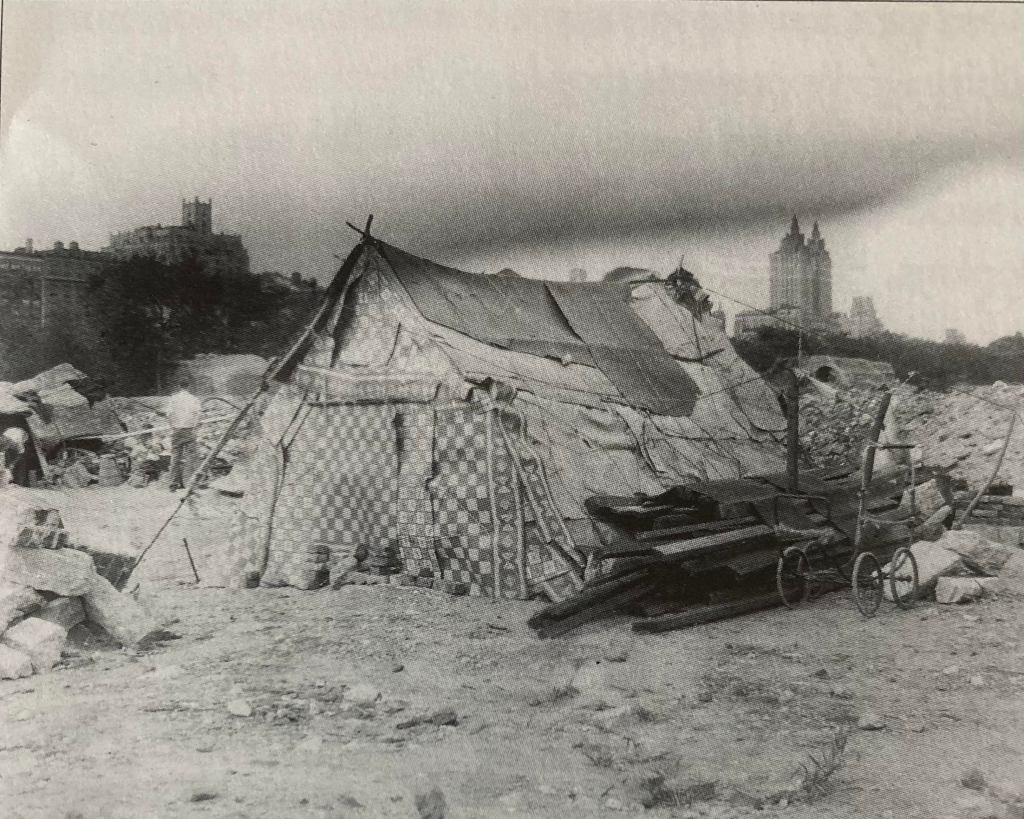

“Fantastic” is Berenice Abbott’s word for the world she sees and seeks to capture in art. Probably it is the right word, too, for it is fantastic that the Chrysler Building, the Daily News Building, Rockefeller Center, the Stock Exchange, and any other of a hundred similar displays of ostentatious and vulgar wealth should exist side by side with those Central Park shanties of the unemployed which she has also photographed.38

Abbott had indeed made a series of photographs of Central Park shanties (fig. 9), but she had neither exhibited nor published them. The overt contrast of rich and poor was McCausland’s, not Abbott’s.

McCausland also noted that “New York is by no means all of America Berenice Abbott loves,” citing their plan to travel together throughout America to explore “a people in the process of forging its soul.”39 That spring, they drove from New York to Memphis, to St. Louis, and back in four weeks. McCausland paid for the trip by writing articles for the Republican, and Abbott took 200 photographs.

They saw stone barns in eastern Pennsylvania, the filthy shacks of West Virginia coal miners, the Norris Dam under construction by the Tennessee Valley Authority, “Negro comfort stations” in southern towns, and Hoovervilles on the banks of the Mississippi River. Exhilarated, they planned a one-year trip to visit all forty-eight states and produce a book which, in McCausland’s words, “could be the great democratic book, the great book for masses of people conditioned by reading newspapers and tabloids.”40 They applied jointly for a Guggenheim fellowship to “make a portrait in words and photographs of the United States of America at the present moment.”41 The plan was inspired but overly ambitious and was rejected. On their return to New York, Abbott and McCausland moved to a loft on Commerce Street in Greenwich Village. Although the smell of cooking fat wafted into the apartment from the building’s first-floor restaurant, the rent was cheap and space plentiful.42 Abbott built her studio on the fourth floor. They lived there until McCausland’s death in 1965, when Abbott moved to Maine.

In February 1935, at Landgren’s suggestion, Abbott had applied to New York City’s Emergency Relief Bureau for funding to photograph New York. In September, that agency was replaced by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration, and Abbott’s application was accepted. As she later recalled, the day she learned she was to become a “project supervisor,” “was the happiest day of my life.”43

THE WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION (WPA) was formed in 1935 to centralize the various public works projects that local, state, and federal governments had established since the 1932 presidential election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Harry Hopkins, head of the WPA, constantly reminded his staff that the agency’s primary objective was “taking 3.5 million [people] off relief and putting them to work … and don’t let me hear any of you apologizing for it because it is nothing to be ashamed of. “44 Despite Hopkins’s rhetoric, the WPA also aimed to convince the American people, especially conservative Congressmen, that government-funded schools, parks, and highways benefitted all Americans. The Federal Art Project (FAP), a relatively small division of the WPA, was a relief agency for artists; its controversial goal was to show that art, as well as schools and highways, contributed to the general welfare. From its inception, the FAP (along with the Federal Writers, Music, and Theater Projects) was particularly vulnerable to criticism by conservatives, who considered artists to be lazy slackers, left-wing rabble-rousers, or both.

The FAP’s top administrators were not professional bureaucrats but art world idealists. The program’s chief planner was Audrey McMahon, president of the College Art Association (CAA), who grew increasingly concerned, as the depression deepened, that a generation of artists, forced into idleness, would be lost. She devised an art program, funded at first by private philanthropy and then with government funds, that produced art for schools, libraries, and other institutions; the CAA program became the model for the FAP. Declining the national directorship, McMahon became Regional Director in charge of the New York City program, which employed 43 percent of the project’s artists. The national post went to Holger Cahill, an American art curator at the Museum of Modern Art.

Abbott knew both McMahon and Cahill. In 1933, McMahon had shown Abbott’s photographs in a CAA traveling exhibition and, as editor of the CAA journal, had published a review of Abbott’s 1934 Museum of the City of New York exhibition. Abbott’s 1935 application went directly to McMahon. Abbott and Cahill’s friendship dated from their Greenwich Village days in the early 1920s. Abbott’s relationship with the two senior FAP administrators explains the ready acceptance of her project, which was unlike any other FAP program.

The FAP was divided into three parts: Creative Projects, in which artists produced work with little institutional interference for display in public settings; Allied Art Projects, in which artists worked on assignment; and Art Teaching, which established art classes and community art centers. Photographers worked in all three parts within the FAP’s Photographic Division. In New York, some photographers, such as Arnold Eagle and Sid Grossman, produced “creative assignments” of their own devising.45 Most photographers, however, worked for what was called the “Hash Project,” taking assignments from cultural institutions or documenting WPA achievements, from subway construction to community art classes. Abbott was the only photographer assigned a staff for her own project, and, as a supervisor, she did not have to prove indigence to qualify for employment. Her role was comparable to a mural painter who directed assistants and controlled artistic content.

Sponsorship by the Museum of the City of New York was also essential to the acceptance of Abbott’s project. As required by FAP regulations, the Museum agreed to purchase at the cost of materials a set of Abbott’s federally funded photographs. Scholle was a member of the FAP New York City advisory committee and helped shape the policy that enabled him to hire seventy-five employees to assist in all phases of Museum activities, from roof repair and security to conservation, research, and exhibit installation. Among the Museum’s FAP workers were photographers who documented collections and the achievements of their fellow government employees.46 Indeed, except for a handful of curators and administrators, the Museum was run entirely by FAP personnel. The relationship between Scholle and the FAP was reciprocal. As a relief organization, the FAP was happy to find a sponsor with Scholle’s energy and creativity.

The FAP gave Abbott what she most desired: a monthly salary of $145 that allowed her to photograph New York City full-time. By giving her a staff, the FAP acknowledged that she could not work “in the spirit of the news photographer who rushes up to a fire, presses a button, and rushes back to the darkroom to develop his film,” that she needed time — and sometimes advance permission — to select her subjects, and that she needed physical help carrying sixty pounds of equipment through the city’s streets.47 Abbott’s other needs were not ideally met. She was assigned less technical assistants and more research assistants than she requested. Administration was not Abbott’s forte, and she resented the extra time and energy that her swollen ranks required. Abbott had also asked for a car, which she deemed an essential; not until November 1936, after fourteen months work, was she allotted a 1930 Ford Sport Roadster, which brought with it a $38.33 per month raise for maintenance. She also sought a recent model miniature camera, “urgently required for certain types of work … if the photograph is to have … spontaneity.” Not until mid-1938 did she obtain two small-format cameras, a Linhof and a Rolleiflex.

Abbott’s bureaucratic problems, however, were relatively mild and were often resolved in her favor. Once when she was struggling to procure supplies, she complained to Cahill at a dinner, not knowing of his appointment as FAP national director. To her embarrassment and the mirth of others, his status was revealed and her difficulties soon disappeared.48 Like all FAP artists, Abbott bemoaned the requirement that she sign in at the FAP’s midtown headquarters — a requirement ill-suited to the work habits of most artists. Opposition to timekeeping engendered a bureaucratic battle that pitted Cahill and McMahon against WPA authorities. Abbott, however, was eventually allowed to transfer the locus of her project to her Commerce Street studio, and thereby to avoid the midtown sign-in.

Once the project began. Abbott devised an “Outline for Photographing New York City.” Although it was not until April 1936 that she named the project Changing New York,49 Abbott always considered the documentation of change her central theme. Introducing the outline, she wrote:

How shall the two-dimensional print in black and white suggest the flux of activity of the metropolis, the interaction of human beings and solid architectural constructions, all impinging upon each other in time?

Abbott rejected the obvious solution of capturing fleeting gestures with a small, hand-held camera. She also dismissed the “architectural rendering of detail [with] the buildings of 1935 overshadowing all else.” Instead, she wished to “show the skyscraper in relation to the less colossal edifices which preceded it … the past jostling the present.”50

Abbott’s thinking about cities reflected the influence of Lewis Mumford’s Sticks and Stones, a widely read book, first published in 1924, after a series of lectures at the New School, and reissued in 1933. Rejecting an aesthetic reading of architecture, Mumford espoused a sociological analysis that sought to explain the relation of “the shell itself to the informing changes that … take place in the life of the community itself.”51 He organized his study of civilizations in three parts: the place, the work, and the people.52 Abbott adopted the identical three-part organization in her outline: “material aspect,” “means of life,” and “people and how they live.”

Abbott’s outline was not just a theoretical construct but a plan of work. Material Aspect was divided into buildings — historical, picturesque, architecturally significant, and deluxe — and city squares. Within each subcategory, such as “picturesque buildings,” Abbott listed topics, such as frame dwellings, and specific sites, such as “old saloon interior, “138 St. and Third Ave.” Occasionally, she editorialized: under “city squares” she noted, “Not postcard views!”

Means of Life was divided into three parts: Transportation (land, water, rapid transit, and airways); Communications (mail, phone, and telegraph); and Service of Supplies (food, water, heat, and light). The third section — People and How They Live —was divided into seven sections: Types; City Scenes (street, night, and civic); Interiors (high and low life); Recreation (theaters and movies, music halls, Coney Island, sports, and parks); Culture and Education; Religion; and “Signs of the Crisis.”

Spread over thirty-one pages with blank space left for additions, the outline was not a blueprint but a point of departure. Only a fraction of the listed sites were photographed, and many topics that were left blank in the outline, such as “transportation, water routes,” were photographed extensively. Abbott welcomed change. After a year’s work, she remarked:

I have had the experience which is a healthy part of every artist’s growth: The more you do, the more you realize how much there is to do, what a vast subject the metropolis is and how the work of photographing it could go on forever.53

Toward the end of the project, Abbott made three lists of potential subjects, one for each camera. 54 The lists included topics as general as “crowded corners” and as specific as “detail of column with capital in center: downtown side of ‘el’ station, 50th St. & 6th Ave.” They reveal the same intuitive working method as the original outline.

Abbott dated her project negatives, and the chronology shows that progress was random, with no systematic approach to a district or a theme. Other than a preference for early spring and late fall when trees were bare and the air was clear, Abbott worked unpredictably, alternating bursts of energy with barren lulls. Outside commitments — teaching, occasional freelance jobs, and exhibitions — contributed to the project’s ebb and flow, but Abbott’s method played a significant part. Before photographing, she accumulated ideas for subjects, sought permission to photograph in restricted areas, and noted optimal times for particular exposures. Once in the field, she courted chance and seized unforeseen opportunities.

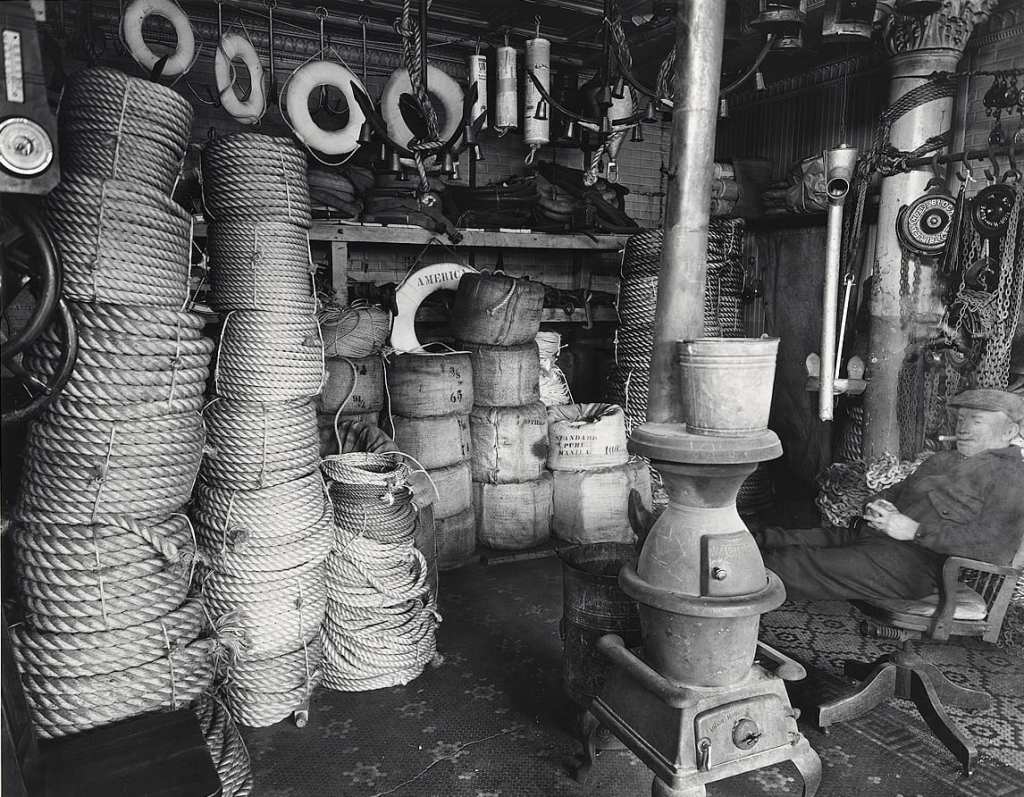

A glimpse of Abbott’s routine was recorded by a reporter who joined her on May 3, 1938, her first day with the Linhof camera.55 Although the light was unsuitably “flat,” Abbott took four photographs, all of which she retained for the project. She first photographed “seven vagrants drunk in front of the queerest looking shack you ever saw” on the East River waterfront (Wall Street Plate 8). Then she drove down South Street and stopped near the Brooklyn Bridge at a rope store, which she had photographed two years before. Trying to capture the reflection of the bridge’s cables in the store’s window, Abbott was pessimistic: “I’m not going to like the result when l’m through. But l’ve got to try it.” An assistant set up the view camera, loaded the film, and chased away passersby who entered Abbott’s field of vision. Abbott asked the storekeeper to bring out more rope and a big winch “which shone like silver in the dull light” (Lower East Side Plate 4). After lunch the group headed for Hester Street on the Lower East Side, a neighborhood Abbott knew well and where crowded streets presented opportunities for the Linhof. Abbott chose two subjects she had already photographed with the view camera. Her assistant convinced a housewife to allow them into her apartment so that Abbott could photograph push carts from above (Lower East Side Plate 12). A few steps down the block at the corner of Hester and Orchard Streets, Abbott photographed a roast corn vendor (Lower East Side Plate 13). Work ended that afternoon when it rained. The four photographs were among nineteen that Abbott took for the project that May, a number equal to the previous five months’ output.

Abbott exposed the last negatives for Changing New York in November 1938, but never finished her plan of work. Particularly incomplete was her work with hand-held cameras. In a December 1938 interview, she vented her frustration:

There are lots of things I could have taken in the last five years, if I only had had better cameras….. You want to get a crowd of people really protesting something. If you try to get the expression on their faces, you are stuck… You want to take a bunch of colored people in a dark corner…. You want to take a subway rush at 5 o’clock… suppose you want to catch a seething mass of people from a bus top.”56

Abbott accomplished only the last of these subjects, Tempo of the City I (Middle East Side Plate 24). Without a miniature camera, she was also unable to explore the final section of her original outline, “people and the way they live.” Crowd scenes, night scenes, and interiors were never investigated, and some of her most colorful ideas — “police in action, mounted, at theater hours,” Broadway shooting parlor, and Italian marionettes on Mulberry Street — and her most overly political ideas — election night, picket line, and Union Square street speeches — were never realized.

Rather than work through her outline, Abbott returned many times to favorite locations. She omitted the Empire State Building but photographed the corner of South Street and James Slip four times (Lower East Side Plates 1-4). She devoted half of Changing New York to lower Manhattan, a preference justified as much by the area’s historical importance as by artistic concerns and sheer whim. The financial district and the waterfront, which formed the crux of New York’s economy, offered Abbott the technical challenge of photographing skyscrapers and bridges. The immigrant neighborhoods of the Lower East Side, set against the backdrop of Wall Street, presented endless contrasts of old and new, rich and poor. Greenwich Village contained many of the city’s oldest structures and was Abbott’s home. Manhattan north of much less appealing. Perhaps her most glaring omission was the city’s middle-class housing — from Victorian brownstones to apartment buildings — which occupied most of the island north of 59th Street; this significant component of the city’s “material aspect” did not even appear in her outline.

As the project progressed, Abbott developed a more daring, experimental style, and her return to a site often signaled a new compositional idea. In re-photographing the Flatiron Building, for example, she replaced a “post card” view, taken from an office building across the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a radically cropped, foreshortened view, taken in traffic (fig. 10 and Middle East Side Plate 11). She rephotographed other sites — Bowling Green, St. Paul’s Chapel, St. Mark’s Church, the Starrett-Lehigh Building, and the New York Telephone Building — in similar fashion. Abbott seems to have discovered this approach in the financial district, where she was forced to point her camera up at skyscrapers from the narrow streets below and used the camera’s adjustments to exaggerate rather than correct distortion. She applied this same expressive technique to other subjects where more conventional alternatives were available.

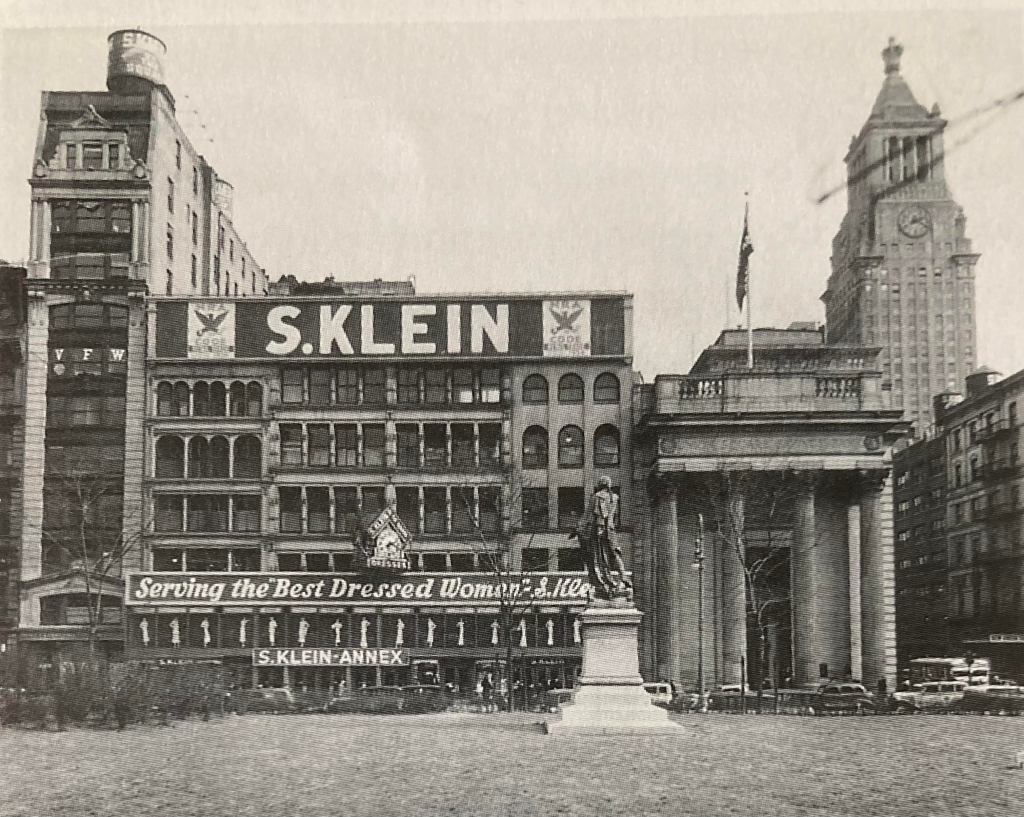

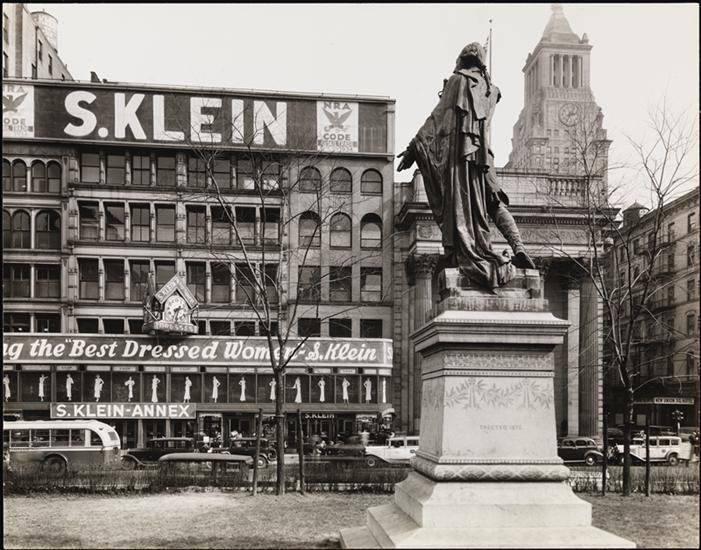

Although she owned few lenses, Abbott often exposed two negatives for an image, experimenting with a short, wide-angle lens and a long lens that compressed distance. In Union Square, she photographed an 1876 bronze statue of General Lafayette against the popular discount department store S. Kleir Yay (fig. 11 and Middle East Side Plate 1). She selected the long-lens negative, in which Lafayette seems to point to the crudely designed storefront, as if he were surrendering nineteenth-century civic ideals to twentieth-century commercial culture.

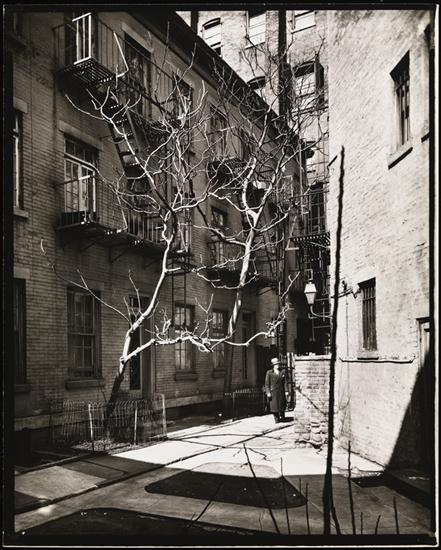

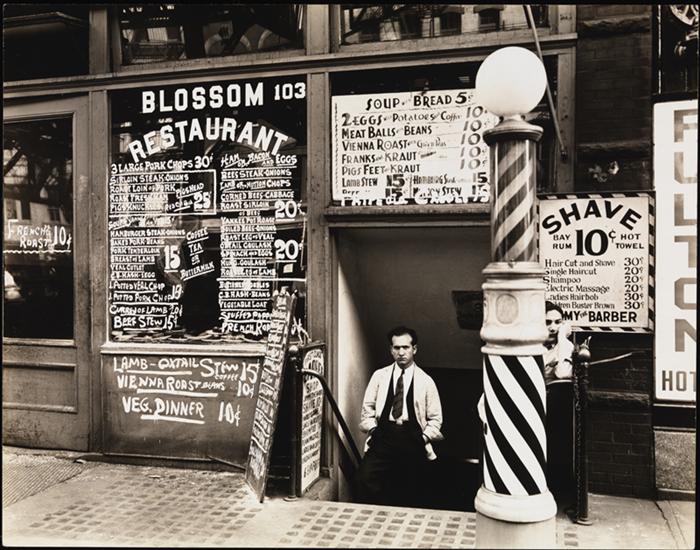

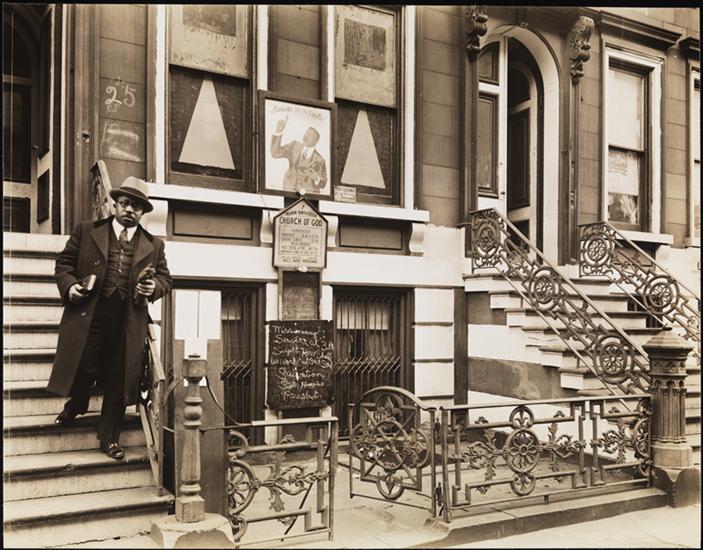

Another of Abbott’s stylistic preoccupations was the placement of figures. Because the imposing presence and long exposure time of the view camera made it difficult to capture movement, her early photographs, like Cherry Street (fig. 5), included only small, distant figures. Later in the project, she had people pose, and sometimes, as in Milligan Place, she exposed more than one negative, asking a person to walk repeatedly into the frame (Greenwich Village Plate 33). On other occasions, she set up the camera and exposed several negatives as different people walked unaware into her composition. Blossom Restaurant (Lower East Side Plate 33) and Church of God are successful examples of this technique (North of 59th Plate 15).

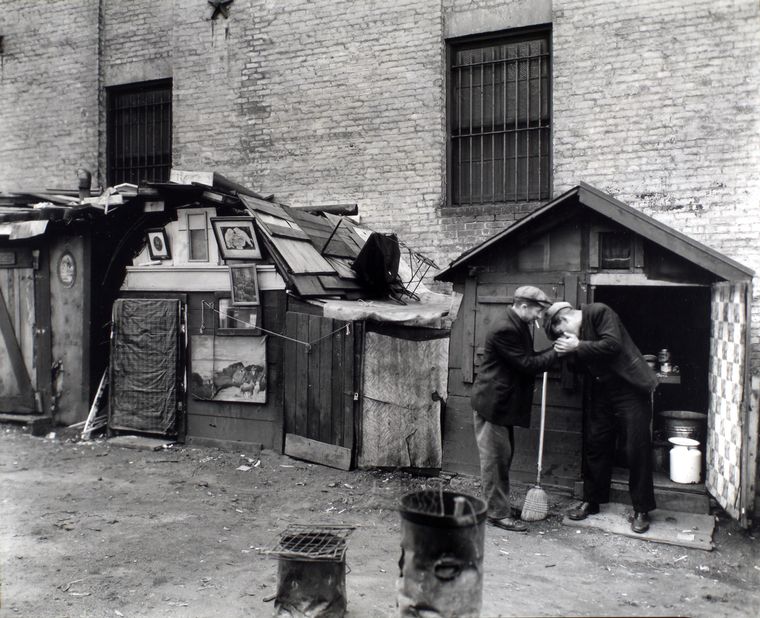

From 1935 to 1938, Abbott took many more images than the 305 she printed for the definitive set of Changing New York. Just as her list of prospective subjects evolved, so did the final selection. When she deemed a negative worthy, she gave a proof print to the research staff, who assigned it a number, title, date, and folder. A researcher then assembled information about the subject — filling in a mimeographed worksheet, writing an essay, drawing a map, or collecting newspaper clippings — and placed the material in the folder. Abbott was constantly editing the files, discarding images as she went, sometimes before a folder was begun, sometimes after one was completed. Many “discards” were kept, and the files were marked “D.” Among the best are Pennsylvania Station, Park Avenue, and a “Hooverville” (fig. 12), all subjects on Abbott’s outline and flawlessly executed.

Abbott’s constant editing was only one of the mysteries encountered by her research staff. The strength of Changing New York lay in the images themselves, each of which met Abbott’s rigorous standard of artistic strength and historical resonance. The project’s weakness was the cataloguing and research process, which Abbott was neither qualified nor eager to supervise. Prior to 1935, Abbott had not acquired the habit of identifying her negatives, and in her original application, research was an after-thought; she asked for “one clerical assistant, possibly two,” to act as secretary and “do collateral research.” She was assigned a secretary and five part-time researchers, each working fifteen hours a week. She had no space for them in her studio and gave them no clear plan of work. As a result, in March 1936, the group was directed to continue working for Abbott but to report to the Index of American Design — a bureaucratic decision that did little to solve the problem.

The Index was an FAP project to document American crafts and folk art from colonial times to 1900. A favorite of Cahill, it aimed to employ commercial artists to produce an encyclopedic resource for the growing ranks of those interested in American material culture. As an Allied Arts rather than Creative Project, the Index was fundamentally different from Changing New York. Its carefully instructed research staff selected objects — from bonnets to weathervanes — which its artists then rendered in watercolor according to strict specifications. The artists’ input was minimal, the objects were not contemporary, and architecture was excluded. Photography played only a minor role as an occasional substitute for drawing and a means of recording the drawings.

Abbott’s researchers worked out of FAP headquarters, without desks or typewriters, under the supervision of Phyllis C. Scott, director of Index research and author of its research manual. Scott gave the researchers data report sheets, which she had designed to systematize information gathering and provide supervisory control. Matters went from bad to worse: without regular contact with Abbott, the researchers never acquired an understanding of her goals, and as she edited the files, their records and hers diverged.

In November 1936, the researchers drafted a ten-page memo of questions and suggestions.57 Using the Index as a model, they recommended that Abbott’s photographs clearly illustrate a predetermined research plan. In her response, Abbott rejected all but a few minor recommendations and provided an eloquent statement of her purpose. She distinguished her “documentary” photographs from the “record” photographs the group was requesting:

[My] photographs are to be documentary, as well as artistic, the original plan. This means that they will have elements of formal organization and style; they will use the devices of abstract art if these devices best fit the given subject; they will aim at realism, but not at the cost of sacrificing all esthetic factors. They will tell facts… [b]ut these facts will be set forth as organic parts of the whole picture, as living and functioning details of the entire complex social scene.58

At the same time, Abbott wrote to Scott’s superior, urging that the researchers return to her and meet with her weekly.59

In the end, Abbott did not change her work habits, nor did she wrest control of the researchers. She did supply them with more information: titles and research instructions for each image, and copies of her original outline.60 Scott standardized the contents of the research folders, and the two sets of records were reconciled. Researchers chose specialties — history, sociology, and engineering — and one devised a street map showing the exact location of each site. The head researcher, Gabriel Haver, acted as liaison with Abbott’s secretary and submitted weekly written reports to Scott. By the end of November, a truce was declared; Haver’s report to Scott stated that “Miss B. Abbott [is] decidedly pleased with work of our unit.”61

Despite these improvements, the researchers’ work left much to be desired. Their output was painfully slow, and the backlog of “untouched photographs” continued to grow. In May 1937, Haver left the project, and in August, Everett Gratama, the map-making researcher, followed; neither was replaced. The filing system for the negatives was riddled with inconsistencies, and the research folders were arranged in a manner that frustrated research — alphabetically by title, with Commerce Street, Cheese Store, and Construction Old and New all filed under “C.”62

In July 1937, Scott reported to McMahon that, “since my supervision of this group has been the cause of continual confusion to all except the persons most concerned, would it not be simpler if the group were returned to Miss Abbott for supervision?”63 The request was not honored, however, and the researchers remained with the Index. When Scott left in late 1937, their weekly reports ended.

Despite her bureaucratic difficulties, Abbott became a standard-bearer for a beleaguered FAP. In 1936, the FAP employed 5,000 artists, many of whom, including Abbott, joined the radical Artists’ Union and the American Artists’ Congress, which demanded a greater government commitment to the arts. Although the unions won some concessions, their protests — most memorably the takeover of McMahon’s offices — made headlines that only strengthened the public’s impression that artists were ungrateful subversives.

Cahill tried to counter the FAP’s bad press by trumpeting its accomplishments. In March 1936, he inaugurated the Federal Art Gallery with an exhibition featuring work by every FAP program. In September, as protesters picketed FAP offices, a second show, New Horizons in American Art opened at the Museum of Modern Art. Cahill wrote the introduction to the catalogue of this vast exhibition of 435 objects, which marked the FAP’s first birthday. He also began planning Art for the Millions, a book of artists statements lauding the FAP for its support. In the proposed book and the exhibitions, which included several Changing New York photographs, Abbott was the sole representative of the Photographic Division.64

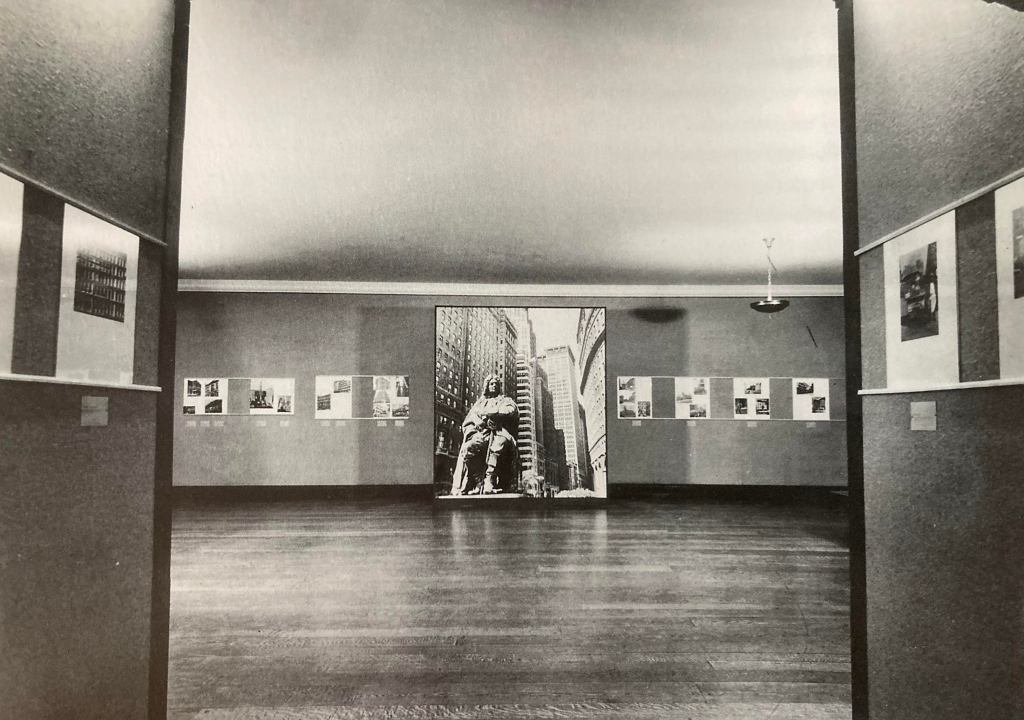

McMahon also showcased Abbott’s work. She solicited Abbott to contribute to a 1936-37 College Art Association traveling exhibition, Photography — A Fine Art, and asked Scholle if the Museum of the City of New York would give Abbott a second one-person exhibition featuring her FAP photographs. That exhibition, Changing New York, opened October 20, 1937, and presented 111 photographs, half the number then in the files. More than twice the size of Abbott’s 1934 show, the 1937 exhibition was installed in the Museum’s large temporary exhibition gallery on the ground floor. The prints were displayed in the same manner as in the earlier show, with varied print sizes and one to four prints per mount. A mural-sized enlargement of DePeyster Statue, Bowling Green held center stage (fig. 13). As in 1934, the exhibition was extended six weeks because of popular demand. Indeed, the only disappointment was Abbott’s research unit. Curator Grace Mayer had hoped the researchers would provide descriptive captions for the photographs and had planned to highlight their work in a special showcase. The researchers, however, failed to meet the Museum’s deadline and missed the opportunity for public acknowledgment.

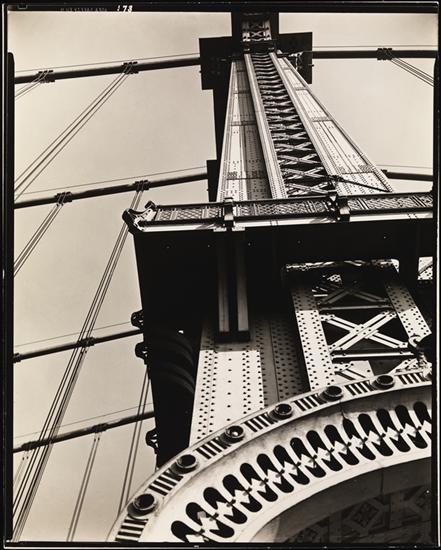

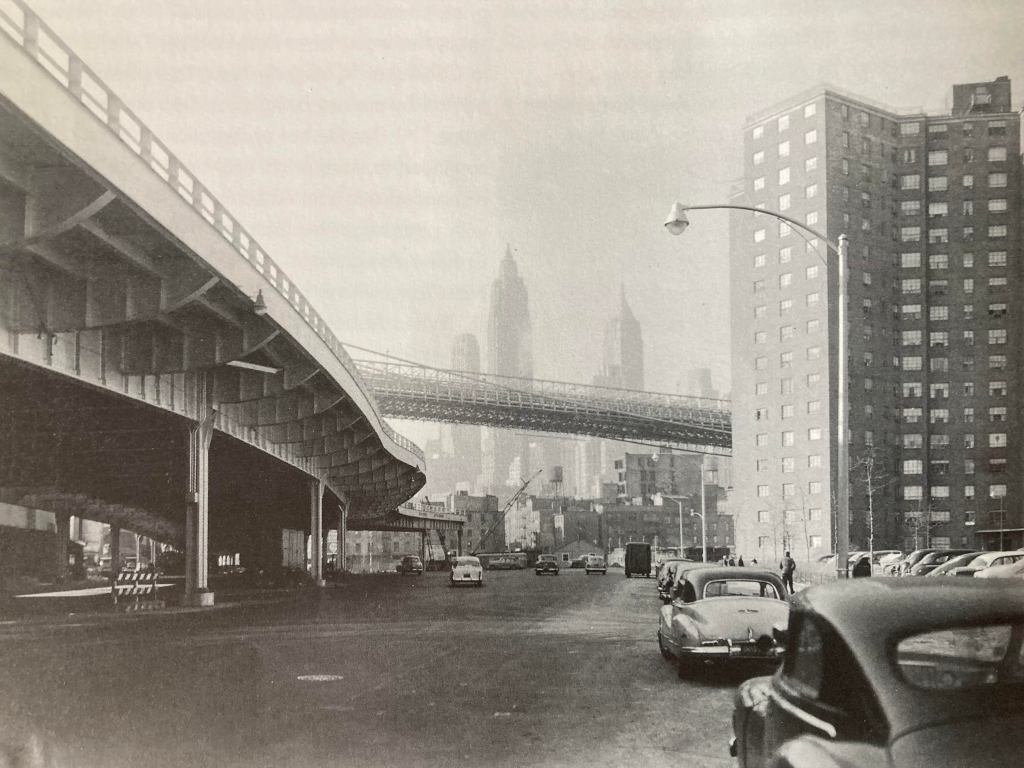

In professional circles, the 1937 exhibition received warm reviews. Beaumont Newhall, who in March had organized the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition, Photography 1839-1937, wrote a congratulatory note offering special praise for Abbott’s “juxtapositions and mounting.”65 Carl van Vechten, who photographed New York’s cultural avant-garde as Abbott had done in Paris, applauded the show and asked Abbott whether he might make her portrait.66 A large reproduction of Manhattan Bridge, Looking Up (Lower East Side Plate 21) appeared in Parnassus, the journal of the College Art Association, and McCausland wrote a laudatory review for the Springfield Republican. The only negative comment came from Robert M. Coates of The New Yorker, who glibly remarked that Abbott “of course” followed in the footsteps of Eugène Atget and “suffer[ed] a trifle by comparison.”67

Abbott’s photographs were not polemical, but in the heated political environment of the late 193os, her sympathies and associations veered left. Her exhibition received broad coverage in the radical press. Under the pseudonym “Elizabeth Noble,” McCausland wrote a review for New Masses; the New York social work review Better Times ran First Model Tenements (North of 59th Plate 3) on its cover; and Abbott was interviewed in the Daily Worker. Writing in Art Front, Abbott’s student Genevieve Naylor compared the show favorably with the more commercial U.S. Camera annual exhibition, noting that the “government project … gives the photographer a chance to express her own ideas free from the standards of most business concerns.”68

Abbott’s political leanings were not so pronounced as to alienate the popular press, and she hired a publicist to supplement the Museum’s public relations efforts.69 In the opening week, seven newspapers ran feature articles reproducing numerous photographs (eight in the New York Post), in and many included a portrait of Abbott sporting a rakish beret and adjusting her unwieldy camera. In November, she was interviewed on radio, and in the exhibition’s final week, Life Magazine ran a story with four full-page photographs.70 After years of telling her tale, Abbott had distilled it to its essentials: her success in Paris, her “fantastic passion” for New York, the period of struggle, and the fulfillment of her dream with the FAP’s support. It was her story as much as her photographs that captured the public’s imagination and made her an art-world celebrity.

Interest in Abbott intensified with the growing vogue in America for documentary photography, which seemed to define every new development in the field. At the Museum of Modern Art, Beaumont Newhall’s historical exhibition and Lincoln Kirstein’s exhibition of Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938) established documentary photography as art. At Rockefeller Center, Henry Luce launched the sensationally successful Life Magazine, which proved the story-telling power of photographs. At Union Square, the Photo League trained young political idealists to employ photography for social change. And in Washington, Roy Stryker’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographic unit stunned the nation with its provocative photographs of the rural poor. Sharing the objectives of social realist and American scene painting, documentary photography outstripped more traditional media in its capacity to reach the masses.

Abbott had declared herself a documentary photographer a decade earlier and now stood at the center of these developments. Newhall featured her work in exhibitions and sang her praise in numerous articles.”71 Despite the sorry state of the 1938 art market, Abbott carried sufficient clout to warrant a one-person show at a midtown gallery.72 At the huge 1938 International Exposition of Photography at New York’s Grand Central Palace, Abbott’s FAP photographs, along with the FSA exhibit How American People Live, were touted as “the most exciting and important photographs” in the show.73 Abbott also contributed twelve prints to Roofs for 40 Million, an exhibition intended to focus attention on the nation’s housing crisis and to advocate for urban planning.74 At the same time, she served on the Photo League’s advisory board and gave lectures and critiques. With McCausland and Newhall, she heralded the social reform photography of Lewis Hine, ranking him the equal of Atget and Brady as a precursor of modern documentary photography.

As Abbott’s reputation grew, however, the FAP crumbled, and she began to fear for her livelihood. Her experience was all too typical; just when the arts projects were hitting their stride, a hostile Congress began its lethal assault. In the spring of 1937, massive funding cuts initiated a two-year political battle which left the FAP an empty shell. By the end of 1939, Congress had stripped the national FAP leadership of its authority and placed the program in the hands of local WPA administrators, who were generally hostile to the arts. Priority was given to the Allied Arts Project, which stressed social service over free expression. Supervisors like Abbott, who received higher pay, were a target of the FAP’s foes, and demotion was often the only alternative to losing their jobs.

In August 1937, Abbott petitioned McMahon to extend the scope of her work to include all of New York State.75 Seeking a respite from wielding her camera in New York City traffic and hoping to examine the neglected remnants of Victorian culture, she may also have feared that the Changing New York exhibition would be perceived as the conclusion of her project. Circumstances worsened in late 1938 when she was demoted to assistant project supervisor, taking a pay cut from $183.33 to $166.66 per week. She applied to the Guggenheim Foundation for support and was rejected a third time. In August 1939, Abbott again sought an extension from McMahon, this time requesting to photograph the New York World’s Fair, which had opened in April. Instead, she was demoted once more and directed to accept regular assignments from the Photographic Division;76 the following month, she received her pink slip.77

In the midst of these machinations, Abbott’s public acclaim and the FAP’s desperate need for favorable publicity created the opportunity for publication of a Changing New York book. Another contributing factor was the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the city’s most ambitious public works project, built on the site of a garbage dump in Flushing, Queens. Anticipating hordes of tourists, New York’s publishers increased the flow of New York City guides, journalistic accounts, and view books to a torrent. New editions of old standbys, such as King’s Views of New York City and the New York Walk Book, were joined by specialty books, such as New York-Fair or No Fair, A Guide to New York for Women, and A Trip to the New York World’s Fair with Bobby and Betty by Fair President Grover Whalen. Several 1920s collections of etchings in the delicate style of Joseph Pennell were reprinted, and photographic books, such as Gilbert Seldes’s This Is New York, appeared for a more contemporary audience. The Federal Writers’ Project produced New York Panorama, a 1938 series of essays with photographic illustrations, and the WPA Guide to New York was published in time for the Fair. The success of Abbott’s 1937 exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York convinced E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., to enter the market, and it contracted with the Federal Writers’ Project to publish Changing New York.78

Abbott had already drawn up a preliminary plan for a book of New York photographs that would combine her earlier work with her FAP photographs.79 For the Dutton book, she was obliged to limit herself to the FAP photographs, a small sacrifice compared to the benefit of collaborating with McCausland, who was hired to prepare the text. For McCausland, the assignment fulfilled her ambition born on the 1935 summer trip to write a book with Abbott. McCausland was a passionate proponent of government support of the arts, not only because it relieved the misery and salvaged the skills of artists, but because it made them “aware of [their] place in society” and their “duties and obligations” as citizens.80 As a critic, McCausland encouraged artists to fulfill their civic obligations and exhorted the government to give artists greater security and freedom. With the Abbott book, she left the sidelines and learned for herself the difficulty of being an artist-citizen.

Hired as a writer, McCausland brought to the assignment her experience as an amateur printer and her thoughts on the layout of photographically illustrated books.81 She designed a mock-up for the first twenty-three pages of the book that juxtaposed questions, assorted facts, and photographs to create a cinematic effect.82 The layout varied; some pages carried only text, some only photographs, and others combined text and image; photographs were centered with margins, placed off-center, and bled to the margins. The last page contained seven small photographs of New York’s bridges, arranged along the left edge of the page like a strip of thirty-five-millimeter film.

By the late 1930s, text-and-picture books were fairly common, and McCausland’s plan was comparable to books such as Metropolis, An American City in Photographs (1934) by popular historian Frederick Lewis Allen. Dutton, however, rejected McCausland’s flexible design for a more conservative layout in which 100 full-page photographs would carry traditional captions. Like a conventional guidebook, the approved design presented the photographs in geographical order, from the southern tip of Manhattan to the north, and east to the outer boroughs. Abbott protested the design in vain, sending Dutton a list of New York guides from the New York Public Library catalogue and “reiterat[ing] that [shel never had in mind a book of this type.”83

The battle lost, McCausland began working with the research unit to prepare the captions for the book. She reported to Lincoln Rothschild, who in 1937 was named director of the New York office of the Index of American Design. The three remaining researchers from the original five — Charles White, Sally Sands, and James Broughton — became the core of an enlarged group of eleven staffers appointed by Rothschild to accelerate the research process and guard against another missed deadline.

If the original research group suffered from Abbott’s neglect, the new group suffered from McCausland’s attention. Her sophisticated opinions and zealous demands intimidated and bewildered the researchers,84 She placed a large “X” through a description written by a hapless new recruit and scribbled sarcastically in the margin, “What the handbooks on composition call ‘fine writing’ — facts are needed.” To the researcher who called a cast iron loft on lower Broadway “an ordinary building,” she remarked, “Who said so!” And she attached these ruminations to the presumably complete file on a coal elevator: “Are they strictly functional? And does their beauty of form derive from the fact that their structure precisely fulfills their function?” Oblivious to the burden she was imposing, she asked the researcher to determine exactly how a coal elevator operates, and added: “Incidentally, how is the city of New York serviced as regards coal? What reserve supplies are available? In event of a nationwide coal strike would the city be seriously crippled for fuel?” McCausland’s prodding continued until shortly before publication, when Rothschild found it necessary to admonish her that “[o]ften a harmless looking question … requires half a day or more,” and to remind her that “[t]he whole purpose of the additional personnel is to make a deadline and … all our efforts should be conditioned by this necessity.”85

In July 1938, McCausland sent a draft of her captions to Dutton, which summarily rejected them.86 McCausland’s passionate, didactic text, sometimes prolix and sometimes eloquent, lacked the quality of detachment that she most admired in Abbott’s photographs. The captions, which Abbott had approved, offered opinions on architecture, politics, art, and photography designed to help the reader to understand the artist’s intentions.

Guided by the teachings of Hitchcock and Mumford, McCausland discerned three architectural eras — pre-Civil War, Victorian, and modern — and believed that the simple, practical forms of early American buildings were exemplars for modern functionalism. Her modernist reading of the pre-Civil War era was most pronounced in her caption for a photograph of St. Luke’s Chapel (1820), in which she detected “that abstractly classical beauty for which Mondrian and Arp strive…” (Greenwich Village Plate 13). Her praise for modern engineering was near ecstatic. About Manhattan Bridge: Looking Up, she wrote: “Every rivet, bolt, nut, screw, beam girder of Manhattan Bridge, as one looks up at it, comes to life as the portrait of integrated technics by which civilization survives” (Lower East Side Plate 21). By contrast, McCausland’s view of Victorian architecture ranged from horror to gentle condescension. About the Children’s Aid Society Summer Home (circa 1890 Outer Boroughs Plate 17), she exclaimed, “What nightmare of architectural ingenuity produced this cross between [H. H.] Richardson and the House of Seven Gables?” She looked on an El Station interior “with a tender and humorous tolerance,” imagining that its designer was “an American artist misguided in his youth [and] forced to turn to foreign precedents for authority” (North of 59th Plate 6).