By Arthur Davis

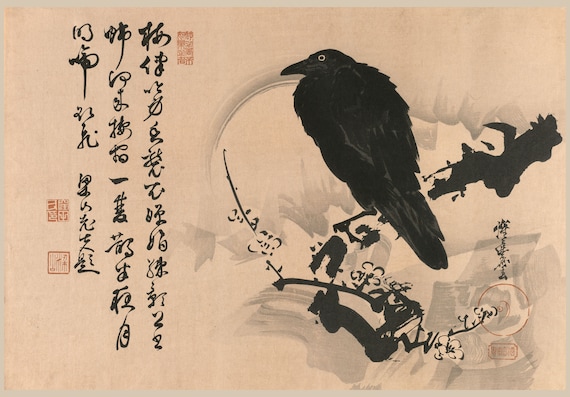

A crow on a withered branch

On a withered branch

A crow is perched

An autumn evening枯朶に 烏のとまりけり 秋の暮

kare eda ni

– Basho

karasu no tomarikeri

aki no kure

Written in the autumn of 1680. Matsuo Bashō was then living in Edo (Tokyo) and teaching poetry to a group of 20 disciples. In this wonderfully simple poem, a crow alights upon a withered branch, and Bashō is moved by the sight to write this haiku.

Kare eda ni

A withered branch, kare eda ni. Much is implied, little is said.

Karasu no tomarikeri

A crow, karasu, alighting on the branch, tomarikeri.

Beyond the obvious phonetic assonance of repeating “Ks” is the symbolism of a solitary crow. Normally we associate these noisy and annoysome birds with flocks. In Japanese mythology the crow symbolizes the will of Heaven.

Gentle reader, I ask: Is Basho the crow, imposing his knowledge and will upon his disciples?

Aki no kure

The final line is aki no kure, autumn evening. This completes the harsh repetition of the K sound, and imitates the cacophonous call of the crow.

Timeline of the poem

Let us visit for a moment with Bashō in Edo. It is still autumn and the leaves are turning red and gold. Winter is about to come.

Perhaps we can imagine Matsuo Bashō sitting on a log in one of the many gardens of Edo surrounded by his student disciples. He is dressed in black, or they are. It is a cool autumn evening and the leaves are gathering at their feet. The students wait in anticipation of what the master is going to say.

Bashō’s poetry was developing its simple and natural style. The point of view in many of Bashō’s haiku is that life (the human condition) is best described as a metaphor. Bashō died at the early age of 50. Perhaps at the age of 36 when this haiku was written he was feeling both the effects of age and the anticipation of death.

Rhyme, rhythm, and assonance

For those who focus more on rhyme, we could translate it as follows: “On a withered bough a crow is sitting now.” It is not a choice I like. Better yet, On a cracked and broken branch sits a crow. Some may think of Edgar Allen Poe’s the raven gently tapping… Others may call to mind Yeats’s line, “An aged man is but a paltry thing, a tattered coat upon a stick…”

kirigirisu, a cricket cries, by Basho

How piteous!

Beneath the warrior’s helmet

A cricket cries.むざんや な甲の下の きりぎりす

-Basho

muzan ya na/ kabuto no shita no/ kirigirisu

Saito Sanemori

An everyday object comes alive when Basho hears a cricket chirp underneath a warrior’s helmet. Winter is approaching.

On the 8th of September, 1689, Matsuo Basho, and his companion Sora, visited Komatsu and the Shrine Tada Jinja 多太神社, the birthplace of the Genji-clan, in Ishikawa prefecture. The shrine was famous as it contained the 12th-century helmet of the Samurai warrior Saito Sanemori 斉藤実盛 who sided with the losing Heike. The old warrior had been brought back from retirement in 1183 to fight in the battle he knew he would die in. To conceal his age, Sanemori dyed his white hair black.

Basho explains:

We visited Tada shirine where Sanemori’s helmet and a piece of his brocade robe are stored. It is said they were given to the Sanemori by Lord Yoshitomo of Minaoto,when Sanemori served with the Genji clan.

-Basho

It was no ordinary helmet. From the peak to the turned-back ear flanges, it was embellished with chrysanthemum arabesques in gold. The crest was a dragon’s head, and the helmet had proud and graceful fla, gilded “horns.”

When Sanemori was killed in battle, Kiso Yoshinaka sent Jiro of Higuchi to offer these relics to the shrine. All this is vividly recorded in the shrine’s chronicles.

The first line of Basho’s haiku comes from a play, Sanemori, by Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443), in which a traveling priest encounters Sanemori’s ghost, who narrates his own story and death at Shinowara. During the clash, Sanemori’s head is struck off, only to be found later by an enemy general, Higuchi Jiro. The severed head is washed in a pond and the white hair is revealed. Recognizing the familiar white hair, Higuchi Jiro cries out “Muzan ya na!” “How piteous!”. Awe-struck with grief, Higuchi Jiro is brought back to reality by the sound of a cricket.

Notes on translation

むざんや, Muzan ya na, clearly more than a simple interjection, muzan conveys the sense of grief and tragedy.

甲, Kabuto, a Japanese Samurai helmet

きりぎりす, Kirigirisu, literally a cricket or a grasshopper and nothing more; unspoken, but implied is the human emotion of crying. A cricket seems less significant to me than a grasshopper, though the two terms were indistinguishable to Basho. Moreover, in Japanese culture, the cricket is an autumn symbol, a sign of approaching winter and death, a kind of melancholy, nostalgic feeling.

Read more of Arthur Davis’ thoughts on Matsuo Basho’s poetry here.

Categories: art, featured, literature, poetry

wonderful. thanks so much!

LikeLike

is it Muzaan ya na or Muzan ya na?

LikeLike