Ezra Jack Keats seems like somebody I’d like to spend some time with. Like Ozu and Tati and Vigo, he seems like somebody who has a lot of answers, who sees things very clearly, but wouldn’t feel compelled to tell you about it. So you’d just have to spend some time with them, to listen and learn.

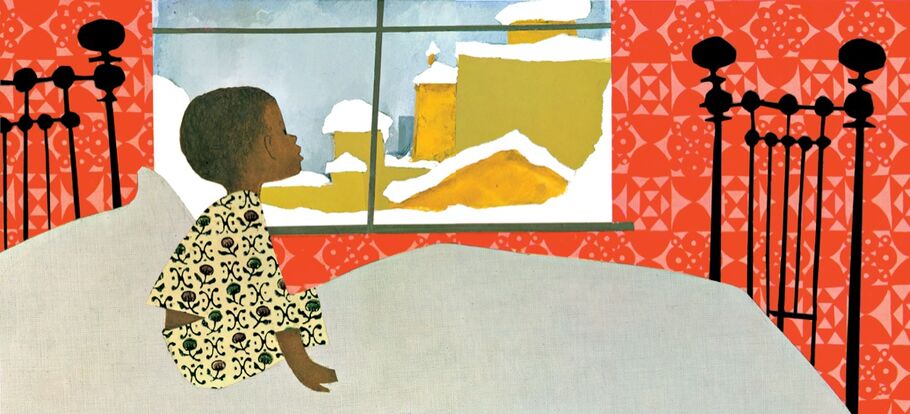

He is, of course, the author and illustrator of The Snowy Day, as well as 21 other books. The Snowy Day tells the story of Peter, a little boy who wakes up to find that it has snowed. And then it describes his day – walking through the snow, making footprints, making tracks with a stick, wanting to join a snowball fight but understanding that he’s too little when he gets knocked down with a snowball, trying to save a snowball and surprised when it disappears in his pocket in the warmth of his house. It’s a perfect book. The language is simple and haiku-like, the illustrations a jumble of color and movement.

The Snowy Day was published in 1962, which also happens to be the year the name of a Crayola crayon was changed from “flesh” to “peach.” Peter is black, but that’s never mentioned in the text, and the book is not about that. In our literary history, black characters had frequently appeared as caricatures or background figures, but Peter is just a little boy, just Peter, so full of personality and charm, so fully conjured with so few words. Keats has said, “My book would have him there simply because he should have been there all along.” The book is about the wonder of walking in a world transformed by snow. “I wanted The Snowy Day to be a chunk of life, the sensory experience in word and picture of what it feels like to hear your own body making sounds in the snow. Crunch … crunch … And the joy of being alive … I wanted to convey the joy of being a little boy alive on a certain kind of day—of being for that moment. The air is cold, you touch the snow, aware of the things to which all children are so open.”

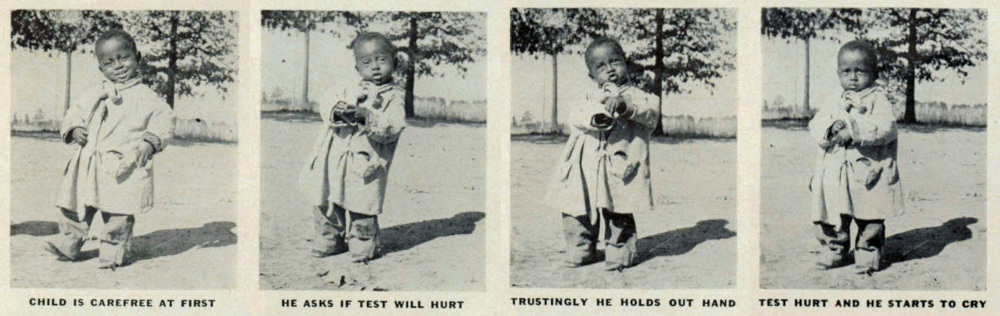

Ezra Jack Keats didn’t have children, but he did have Peter. In interviews, Keats sounds delightfully and perpetually surprised by Peter, the way we are by our own children or children we know. The character was inspired by a clipping from Life Magazine of a small boy whose gestures and expressions were appealing to Keats. He’s surprised, when he first draws Peter, to realize that he’s been carrying the clipping around for two decades. He describes Peter as being so real to him that he almost observed him, rather than writing stories about him or drawing him. After three books about Peter, Keats is surprised to see that he’s grown, he’s bigger, he’s older. Keats wasn’t aware of it, and when he noticed, he was surprised, “He grew without me knowing.” Which is how children grow, how we all grow and change and age.

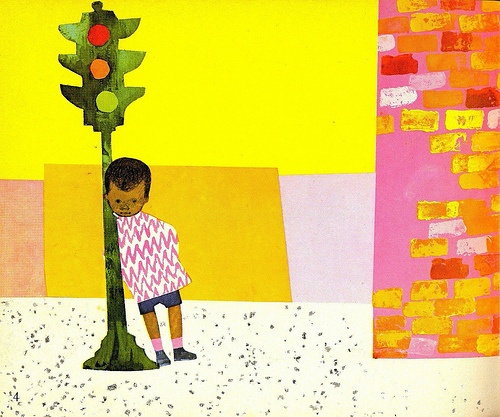

The problems facing Peter in A Snowy Day and other books are small (to an adult) and real – not as dramatic as being chased by death eaters, maybe, but all the more compelling for being universal and recognizable and honest. The predicaments and hopes and adventures may seem unimportant to us, but as everyone who has ever been a child should remember, to a child they are all-consuming. Can’t you remember the swell of emotion of wanting something very badly, (how to whistle, to own a hat) can’t you remember the fear of losing something or the anxiety of being chased by bullies? Of course you can, those feelings stay with you through life, and return to you in small and unexpected glancing moments.

All good books and films about children are not about having children or about an adult’s ideas of how children should behave – not cynically appealing to what some focus group has suggested would sell to a certain age group. They’re about being children, about always being a child in certain situations, like when the snow falls. or when you feel inadequate or disappointed, or left out of a crowd.

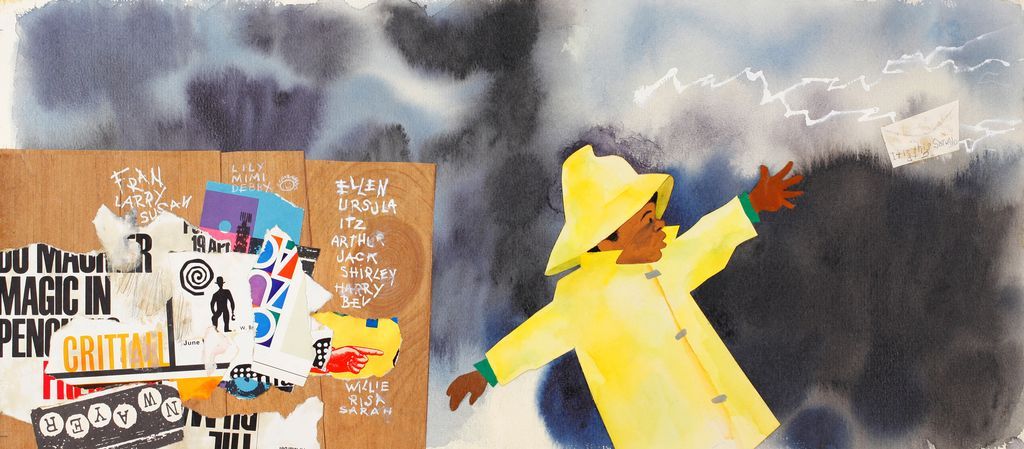

Keats has said that discovering collage made him feel like “…a child playing…I was in a world with no rules.” And this feels exactly how children live and create … pulling a bit of something from here, a scrap of something from there, and piecing it all together in their teeming, colorful little brains. It’s a good way to experience the world and connect everything you see, hear, and feel … aware of the things children are so open to.

Categories: art, featured, literature