By Sophie Dufays

dir. Román Chalbaud; prod. Abigail Rojas, Mauricio Walerstein; screenplay Román Chalbaud, José Ignacio Cabrujas; photography César Bolívar. 35mm, color, 120 mins. Gente de Cine, distrib. Video Games de Venezuela.

Frequently claimed by critics as the best Venezuelan film ever made, El pez que fuma, Ramón Chalbaud’s fifth feature-length film, was produced in the midst of the Oil Boom era and has since become a potent metaphor for the decadence at the height of Venezuela’s economic splendor. The film takes its title from the name of its main setting, a bordello-cabaret in the outskirts of Caracas, run by La Garza (played by Hilda Vera). Along with the centrality of the cabaret and its characters, both the didactic aspect of the narrative schema and the signifying use of sentimental popular songs (bolero and tango songs, most diegetically performed at The Smoking Fish) are highly recognizable ingredients of Mexican Golden Age melodramas, especially the cabaret melodrama as typified by Emilio “Indio” Fernández’s Salón México (1948) and Víctimas del pecado (1950).

Chalbaud’s personal admiration for Mexican Golden Age cinema can be traced from the very beginning of his training as a filmmaker, both in his assisting Mexican director Víctor Urruchúa’s two Venezuelan features in the early 50s and in his own first feature-length film, Caín adolescente (1959), based on his play of the same title. The social content of this first film focused on poverty and urban migration, molded through typically melodramatic characters, climaxes, gestures, and settings, including the cabaret (see Paranaguá 165; Alvaray 43). More generally, “the connection between Mexican melodrama and its Venezuelan counterpart” has largely influenced the emergence of Venezuelan cinema since the 1940s (Alvaray 35). More than mere imitations of the Mexican model, Chalbaud’s films demonstrate an ability to appropriate classical melodrama, reinventing it based on certain Venezuelan cultural conventions—from a reflexive and ironic, yet also nostalgic perspective.

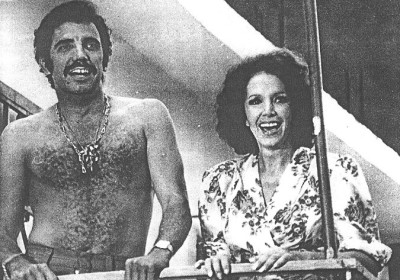

Such appropriation is manifest from the opening sequence of the film, in which La Garza and her lover, Dimas (played by Miguel Ángel Landa), together with the other inhabitants of the brothel, celebrate the arrival of new mattresses while, in a street down the hill, the old ones are burnt in a bonfire encircled by dancing children from the neighborhood.

Such appropriation is manifest from the opening sequence of the film, in which La Garza and her lover, Dimas (played by Miguel Ángel Landa), together with the other inhabitants of the brothel, celebrate the arrival of new mattresses while, in a street down the hill, the old ones are burnt in a bonfire encircled by dancing children from the neighborhood. This sequence sets out a series of didactic contrasts, dramatic ideas, eccentric characters, and excessive emotions that the film will subsequently develop in allegorical and melodramatic ways. Among the contrasts, we find the opposition between new and old, between material comfort and misery, and between the bordello set upon a hill and the surrounding urban area. The image of the bordello’s cashier peering through his telescope brings out the notion of controlled space. The “cripple” guarding the cabaret’s entrance is a clue to the eccentricity of many characters, while excessive gestures and feelings are introduced through the disproportionately hysterical exaltation expressed for the new mattresses. Combining all these narrative, formal, and emotional features, El pez que fuma merges the tradition of 1940s and 50s Mexican cabaret melodrama with another trend of Latin American cinema: namely, the use of allegory, especially as systematized in 1960s Brazilian Cinema Nôvo (Rodríguez).

But even before this first sequence, the credit song—a bolero track, “El preso” (“the prisoner”)—synthesizes the melodramatic and allegorical operations of the film. The recurrence of the song in the last sequence and its lyrics confirm the notion of fate as well as the principles of symmetry and repetition, that structure the plot, the spiral line of which is simple. It begins with the arrival of young Jairo (played by Orlando Urdaneta) at the bordello—who has been sent by Tobías, La Garza’s former lover, now in jail. First hired as a handyman, Jairo gains La Garza’s trust and ends up struggling with Dimas for her sexual favors and the right to administrate the brothel, which amount to the same thing. The two procurers’ ascents are symmetrical, and Dimas follows Tobías’ fate. The song “El preso” therefore not only predicts the similar destiny of La Garza’s lovers and suggests an association between the spaces of the jail and brothel, but furthermore crystallizes the complex role of songs in the film, linked to their cultural and intertextual meanings as well as their affective functions. This 1951 song, recorded by emblematic Puerto Rican singer Daniel Santos, operates as an underlying reference to melodrama as a cultural mold in Latin America (Martín-Barbero)—a reference posteriorly popularized by Luis Rafael Sánchez’s 1988 novel, La importancia de llamarse Daniel Santos.

Indeed, more than an illustration of the characters’ feelings or thoughts, and beyond their didactic function as commentary on action in a Brechtian way, the songs in El pez que fuma “work as a source of dramatic energy. The use of music is a constant stroke of inspiration, an appeal to the complicity of a public well acquainted with the familiar repertoire” (Paranaguá 169). First intermittent, the songs become more and more frequent until they reveal themselves as the motor of the plot in the last part of the drama, when Jairo betrays Dimas, and La Garza is killed by an accidentally fired bullet. During these last twenty minutes, songs follow each other almost without pause, replacing dialogue and highlighting music’s dominant role in the narrative dynamics, portrayal of characters, and discursive functions of the film, as well as its communicative strategy based on shared cultural clues and affective power (Piedras and Dufays 2019).

She is a complex character who synthesizes and subsumes the polarized archetypes of classical Mexican melodrama: overcoming the stark distinction between the mother and the prostitute and claiming a power equal to that traditionally reserved to the macho.

The construction of La Garza’s character—strongly connected to old boleros and tangos—also showcases Chalbaud’s singular appropriation of the Mexican tradition of melodrama. An independent, self-made woman—famously stating “I haven’t had men, I’ve had meters of men, kilometers of men, motorways of men”—she is a new version of the “devouring woman” and, as such, a descendant of Mexican star María Felix. But she is also capable of compassion and motherly feelings. In sum, La Garza appears as a matriarch, a new kind of mother, the mother-owner of the sex workers and, allegorically, of the country (Rodríguez). She is a complex character who synthesizes and subsumes the polarized archetypes of classical Mexican melodrama: overcoming the stark distinction between the mother and the prostitute and claiming a power equal to that traditionally reserved to the macho. Alvaray estimates that she “embodies a new kind of empowered female subjectivity that, nonetheless, is nullified in the end when she is accidentally shot.” (46)

…the songs in El pez que fuma are melodramatic and allegorical tools, participating in Chalbaud’s project to denounce the corruption of a Venezuelan society defined by power struggles in which sex serves solely as exchange value. Yet the songs also transport a nostalgia for an era in which it was possible to dream of true love and to believe in moral values…

Her death and the subsequent vigil are underlined by an emblematic song—the classic 1935 tango “Sus ojos se cerraron”(“she closed her eyes”), composed by Carlos Gardel and Alfredo Le Pera—interpreted by a singer-prostitute called “La Argentina.” The aesthetic and dramatic excesses of the sequence—with repeated slow-motion shots of her body falling—are at once emphasized and given reflexive value through this tango track, which works as an intertextual reference to the more classical tradition of melodrama. The song’s melodramatic theme of deceptive appearances crystallizes the symbolic meaning of action in the film, both at large and specifically in the hyperbolic final scene when the vigil gives way to the habitual festive ambience and La Garza is replaced by a younger prostitute. Contrary to traditional melodrama, here the plot does not offer any moral resolution: La Garza’s death is not interpreted as a result of her lack of moral convention. However, the songs do indeed provide the means for a moral critique of the society represented by the cabaret community. Along with “El preso” and “Sus ojos se cerraron,” the songs in El pez que fuma are melodramatic and allegorical tools, participating in Chalbaud’s project to denounce the corruption of a Venezuelan society defined by power struggles in which sex serves solely as exchange value. Yet the songs also transport a nostalgia for an era in which it was possible to dream of true love and to believe in moral values—those values embodied by traditional melodrama. Summing up, in its nostalgic and reflexive appropriation of old tangos and boleros, El pez que fuma represents one kind of inflection of classical, especially cabaret, melodrama in 1970s Latin American cinema.

References

Alvaray, Luisela. 2009. »Melodrama and the Emergence of Venezuelan Cinema.« In Latin American Melodrama: Passion, Pathos, and Entertainment, edited by Darlene J. Sadlier, 33-49. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Martín-Barbero, Jesús. 1987. »Melodrama: el gran espectáculo popular.« In De los medios a las mediaciones, 124-32. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

Paranaguá, Paulo Antonio. 1997. »Román Chalbaud: The National Melodrama on the Air of Bolero.« In Framing Latin American Cinema: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, edited by Ann Marie Stock, 162-73. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Piedras, Pablo, and Sophie Dufays. 2019. »Canción popular, melodrama y cabaret en Bellas de noche y El pez que fuma.« Chasqui: Revista de literatura latinoamericana 48 (2): 53-69.

Rodríguez, Omar. 2007. El Cine de Román Chalbaud. Retrospective Theses and Dissertations, 1919-2007. University of British Columbia. doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.14288/1.0100501.

This article first appeared here.

Sophie Dufays holds a PhD in Languages and Literature. She worked for around fifteen years (2006–2021) as a researcher and lecturer in the field of Hispanic American culture (more particularly cinema), notably at the universities of Louvain-la-Neuve and Leuven.

In 2022, she shifted her career toward an administrative position focused on coordinating interuniversity exchanges in the Wallonia-Brussels Federation (she is working for the non-profit organization CRef.