By Chimezie Chika

The idea of a self-portrait—with all its associated fixation with the artist’s own inner world—has fascinated artists for a very long time. Many an artist of yore and the present time has gone into that inward world of self-examination rather than look externally into their surroundings. However, the idea of going inward can also be a response to the exterior world. Many artists employ the self-portrait as a barometer to measure their responses of certain events over a period of time, or even as a reflection of the passage of time itself. The reasons can be biographical too, or harken to more oblique intentions. Which would explain why artists as disparate as Rembrandt and Salvador Dali have employed the artistic resource of the self-portrait.

Whatever the motivation might be, the one clear point of contact is that the self-portrait is the artist’s emotional reaction to interior or external phenomena. One of the most famous self-portrait artists was the Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, whose fierce self-portraits are intense documents of her turbulent emotional life and the troubled physical health that plagued her throughout her life. The same can be said of Vincent Van Gogh, whose austere visages of his own were studies of his own suffering.

For Nigerian photographer, Ifeoluwapo Rachael Okunade, the idea of the “self” is not necessarily hers, but an attempt to excavate the different personalities that inhabit the individual. She employs the technique in her photography to examine and reevaluate the evolving meaning of identity. There seems to be a logical trail to this, given how photography relatively developed not too long ago. The self-portraiture in photography is often a tool of self-discovery and emotional expression.

Ifeoluwapo inverts the very idea of the self-portrait as a means to explore identity and emotional well-being. Here, the focal point is not her, but her subject, whose identity she atomises in pixels. Ifeoluwapo applies this method because her work goes to the heart of what it means to be a woman in a world in which a woman has to conform to different roles within and outside the confines of what she calls home. The multiplicities that come from the taking of several photos of a subject in the same way creates islands of such self-reflective duplicities. We see this in the first of Ifeoluwapo’s “selves” photos.

The first photo before us, simply titled “Portraits of Many Selves”, is a slightly pixelated photo shrouded in tones of blue, maroon, and brown. The central image is the female figure covered with a layer of blur (due to the not-fully washed pixels); she’s in a sort of blue gown, along with a blue hijab that covers most of her head except her face. Beneath the hijab, yet visible from the front, is a queen’s crown. Her eyes are gazing directly upwards towards a place beyond the frame, and her entire profile is beatific, as if she is enacting a ceremony among angels and spirits.

Now the interesting thing here is the editing of the photo. Asides the deliberate blur, the figure is replicated beside the main figure and put in greater shadow. The effect appears like an exact replica spirit version of the subject hovering over her physical self. Ifeoluwapo is consciously creating a visual dialogue between an inner and outer self. Her idea here is that the inner self has a strong influence in how the outer self is seen.

In psychology, the duality of a person’s identity is recognised as a response to the necessity of varied social interactions. In one paper by Jimenez and Tsakiris, they note that the interior and exterior perceptions of the self are simply reactions to one’s own view of one’s self. They conclude that “[s]elf-perception is characterized by a strong affective element, experienced as the feeling of being or seeing ‘me’ ”. The selves—these vague versions of the same person. Ifeoluwapo fashions out of her subject an opposition to the main dominant image without conflicting it.

The second version of the “Portrait of Many Selves” photo is also similar to the first in the nature of its composition. The same hues and colour prevail, and the subject is captured in more or less the same posture. But here—and this is quite telling—the selves have been triplicated. The triple visages of the subject are captured in different angles. The first seems to be looking directly at the camera; the second enacts the pose in the previous photo (and of course it’s the same subject, make no mistake); the third is looking almost the same as the second, but the gaze is tilted slightly to the right. The potpourri of colours indicating the clothes have been blurred, through editing, into a tableau more akin to impressionistic brushes of some blue shades and some brown. The visual effect is more like feathers than clothes.

The similarity of the facial expressions here belies the slight differences: the first face is smug, the second is supplicant, and the third (which we, again, cannot fully see, for it’s slightly turned to the side) is filled with something akin to gratitude. Much of this difference is evident in the eyes and the mouth. This is all a testament to the fact that human beings are able to harbour paradoxical emotions within the same mind; many of such opposing emotions can even be expressed simultaneously. Which is why sometimes we may observe that simultaneity of a person’s emotional responses may show through ambiguous facial expressions, because different emotions are trying to work themselves out at once. At that time, the different selves that exhibit different emotions are in conflict.

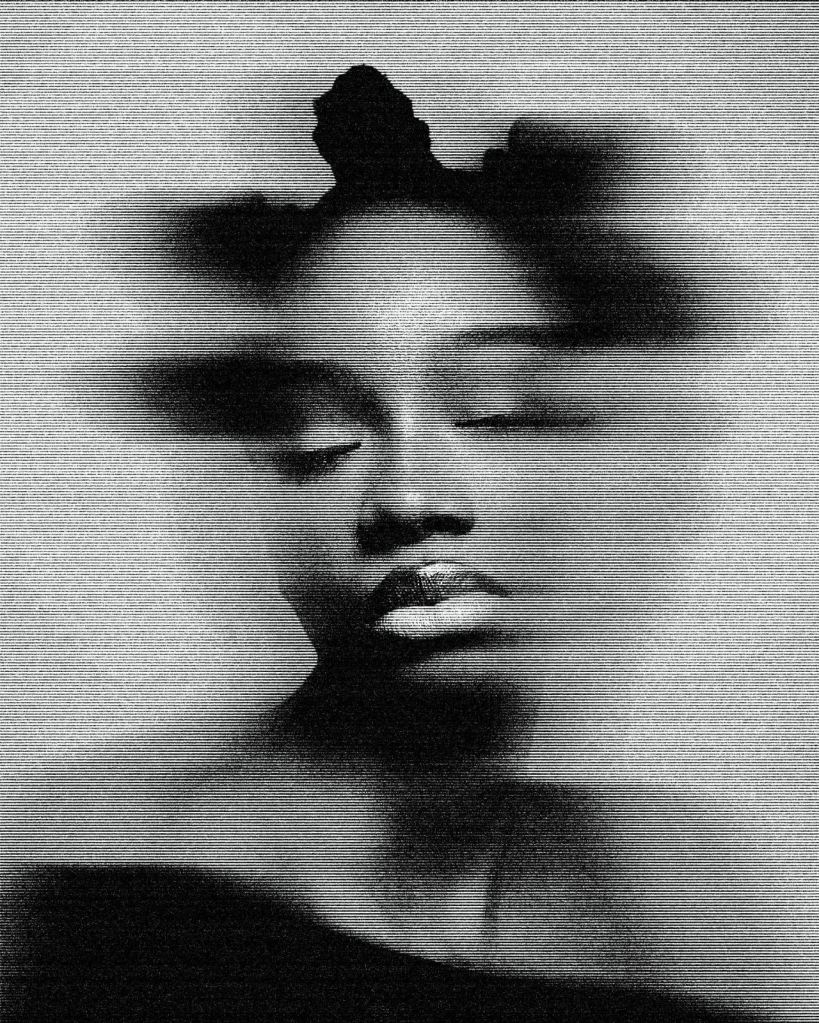

Ifeoluwapo’s third photo titled, “Whispers in Motion: The Blur of Memory and Self”, similarly employs the same blurring technique as the earlier ones as a way to show what the human self expresses in movement. Movement and art have fascinating kinship. It is even more so in photography, where the moving picture has assumed a whole genre of its own.

The photo here captures the face and upper torso of a woman. Asides the prominence of her nose and lips, we immediately see that her eyes are closed as if she’s determined to get to the depth of a feeling (the way people close their eyes to feel more deeply). It seems so given how her head is positioned, leaning to one side. This tilt seems to be enhanced majorly by the blur (which we will come to shortly). Another significant feature on the subject’s face is that her hair is in Bantu knots, a contemporary African urban hairstyle for women, which may indicate decent social conditions for the woman.

The photo’s major attribute is the blur; its narrative is inherent in the blur technique. While we noticed almost all the woman’s facial features, we can also see that her face is nearly in a state of erasure; her left cheek is almost nonexistent. The same can be said of her hair, which appears to be dissipating into thin air. Yet, despite all these, the blur here certainly does not indicate movement or motion; we do not see how the tilt of her head can be from any sudden movement; instead the blur gives a sense of erasure, of disappearing.

We get the impression here that Ifeoluwapo’s imbuing of blur is more about creating a sense that the self is a product of perception, and therefore, what you see depends on the mood of the viewer; that is, the interpretation of the photograph is about what is felt rather than necessarily what is seen. This perceptive emotional realism seems to dominate Ifeoluwapo’s approach to photography.

This emotional world can only be achieved through the peculiar consciousness of her editing practices. The peculiarity of the visual language is its ability to enhance what Roland Barthes called “the referent”. In Ifeoluwapo’s photos, there are multiple referents; these referents are the orifices through which we can penetrate the emotional depths of her photography. In Ifeoluwapo’s photography, we are able to excavate the dualities of facades and selves that define her exploration of femininity. Even when the visual language of Ifeoluwapo’s photography sometimes falls imaginatively into the surrealistic, it is our own standard individualised response that makes us notice where it fits in her emotional canvas.

Chimezie Chika is an essayist, critic, and writer of fiction. His works have appeared in or forthcoming from The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, Channel Magazine, and Afrocritik. He currently lives in Nigeria. Find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, photography