Neal Rantoul’s career as a photographer has spanned decades. He studied with some of the most notable photographers in American history and went on to pass their knowledge to others as a teacher. He has traveled the world, and his subjects span from vast lofty plains seen from afar to more intimate studies of manmade oddities and landscapes. In his work and his writing, he seems to be always asking questions about the art and science of photography, its purpose, its history, its future, and its relation to our lives as humans. We were grateful for a chance to ask him a few questions about his work.

Magpies: I’m fascinated by your aerial photos. They capture human activity from a surprising point of view: the things we plant and build and destroy. But they capture something bigger, too, the sweep of the earth and the sky, cloud and winds and water, that was there before us and will be there after us. I’m curious about the inspiration for your aerial photos and the logistics behind creating them.

Neal Rantoul: Aerial work started with some of the earlier years in shooting Wheat. By 2001 or so I had been to the Palouse to shoot wheat a few times with the 8 x 10 camera in black and white. This one trip in 2001 had me flying from Boston to Seattle, then flying in a smaller plane east, back to Pullman, ground zero for the Palouse, the wheat-growing region of SE Washington. On that short flight across the state, we flew over many of the wheatfields I’d been shooting for 5 years or so on the ground. OMG! This was exceptional and very exciting. So, the next year shooting wheat I hired a small plane and a pilot and up we went, me shooting through a hole in the floor of the plane behind the pilot, lying on my stomach, shooting straight down with the Hasselblad Superwide. I was shooting film in those days. Back at home in my darkroom as I started to make the prints, I realized I had crossed some sort of threshold. My work was about to change. I’ve been making aerials ever since.

Some of the aerial photos are peaceful in a distant, quiet, rhythm-of-the-earth kind of way. But the fire damage photos ask more questions, are a little more disturbing. Forest fires are often the result of human carelessness, whether it’s infrastructure damage, an untended fire, or a larger pattern of climate change. Did any of this inform your photographs or the subjects you chose?

I get where the questions come from but if you’re on the inside of making pictures as a career it isn’t quite like that. You have to follow your gut, and it isn’t until later that you can look back and realize how one project possibly informed another. I knew that the fire damage work was far more dark than other series but was driven by a fascination with what it all looked like and how it had devastated the Paradise community. By that time (2019), I was regularly photographing aerially wherever it was that I travelled to make my photographs. Aerial photography is just now part of my methodology. There was no question that I wouldn’t photograph Paradise from the air. It was the only way I could communicate the vastness of the whole town being burnt to the ground.

For some reason, the fire damage photographs remind me of your photos of taxidermied animals, in the sense that they examine our relation to nature. In this case, our attempts to capture it in ways that often end up seeming glaringly unnatural. Can you talk about your Cabela’s series?

Cabela’s came about really as a matter of chance. A friend and I were coming back from a shoot in Hershey, PA (on my site as: Hershey). We were driving through rural PA and up the hill was a Cabela’s. My friend asked if I’d ever been to a Cabela’s. My answer was “no, what is that?” Once inside, I started fantasizing about being able to photograph inside this huge store with its central taxidermy mountain of stuffed animals in situ. When back at home, I began the process of getting permission and found the marketing guy at company central in Nebraska who said sure, let me know how I can help.

That led to me being allowed to photograph by entering stores at dawn before they were open, when the staff were stocking shelves. One trip, in the winter, I flew to Chicago, rented a van and photographed 17 stores in the Midwest in a few days. This was in 2006 and I was new to digital photography. Also, I was a landscape photographer so had much to learn that trip. I learned on the run as I could see the day’s pictures at night on my laptop, trying to do better at the next store the next day.

Your monsters, mannequins, and medical museum photos seem like such a fascinating and unusual way to examine the human condition. Our fragility, our mortality, our susceptibility to illness and injury. There’s something absurdly endearing in our attempts to ward that off by turning it into something superficially attractive (mannequins) or into something grotesque and frightening (monsters). Can you talk about some of the ideas behind these series, and how they might have changed as you worked on them?

Again, thinking so much about the connections between bodies of work in an analytical and mannered way is not so much a part of my process. Work accrues and assembles in reaction to circumstance and probably relies upon personal growth and experience, and, last, in reaction to what we see and feel. I am reliant upon my own sensibilities to make my art and have to lean on and trust what I have. This can be difficult. There are valleys when there are no ideas, there are hills that feel like personal triumphs. There are times when just coming off a body of work and ideas aren’t flowing. Those can be hard.

I guess on another level, photography is another way to stave off the effects of time. To capture a moment or memory and keep it safe from decay, whether it’s a snapshot, an Instagram post, or a work of art. Do you think about time passing, memory, mortality in your work?

At 78, I do think about my own mortality, but do not believe that my pictures have stopped or frozen time. More, that they are timeless or that they span time, perhaps. I have a book that deals with this, what I call “Photo Time,” which is a very odd thing, freezing time from moving on at 1/250 of a second or so. This is from the Book page on my site:

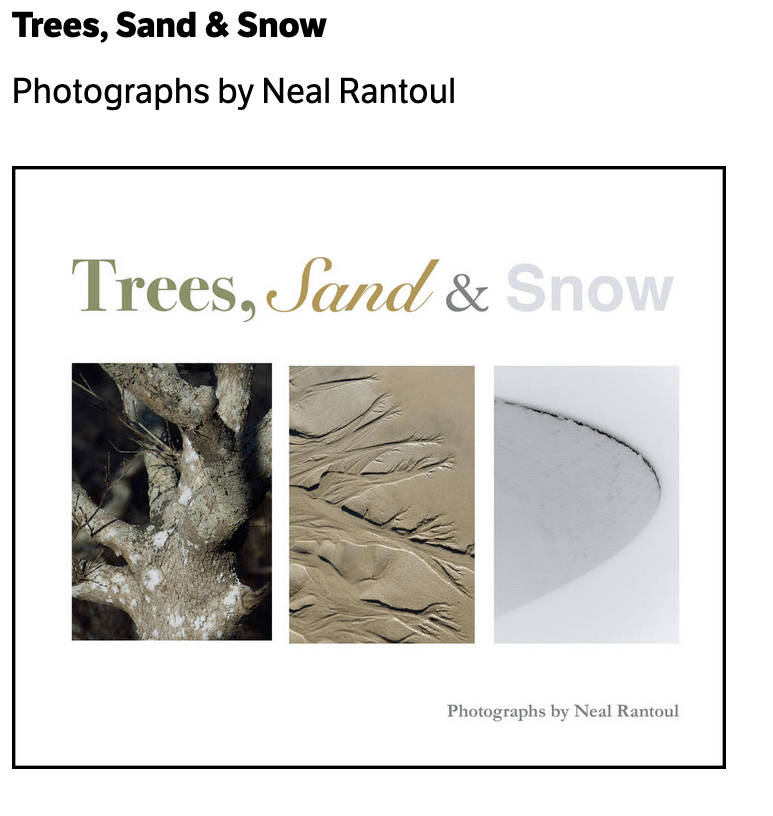

This book, with its chapters “Trees”, “Sand” & “Snow”, constitutes my effort to bring together three locations seen in parallel ways, and therefore to marry different content and conditions into a cohesive reflection on disparate places. If analogies can suffice, then each chapter looks at the commonality of our lives through the filter of our age and our perceptions throughout our time here.

Neal Rantoul, from the introduction to Trees, Sand & Snow

Life is short, as the saying goes, and I believe we are never more conscious of this truth as when we have little of it left. Frankly, at twenty-five, I never would have seen the pictures reproduced here in this book. My concerns were different, faster and not so deep; I was almost never reflective, and certainly never looked over my shoulder. But it is a fact that I have made much more work of substance in my past than I will make in my future. This is comforting because, thinking back to goals and aspirations, I remember, at that same age, it seemed the job at hand was to make good work. This I have done.

As a career artist, it might follow that in my retirement from my teaching career, I might retire from this compulsion to make work as well. Yet I have not. For my passion for making art is as high as it has ever been. I believe that most artists do not retire; they die. Finally, I can see things, I can find significance in things I never could before. Part of the trick to living a life well, I believe, is to know what you are at each age, to adjust, change, and mature to where you are now, with losses, yes, as you grow old, but also gains in perspective, ability to see, and to understand. We know who and what we are better when we age; I know what I am not and what my proclivities and aesthetic are far better than I did fifty years ago when I was starting out.

It’s clear from your writing that you admired your teachers very much, and their ideas and work were a big influence on your ideas and work. I imagine that teaching was important for you in similar ways. The idea of teaching photography is interesting to me because it involves so many disciplines: science, math, technology, composition, light, shadow, art, as well as the history of the medium. Did teaching help you grow as a photographer?

I often said that I was a far better artist, being a teacher. And, I always felt that being an artist was a hugely inward and selfish way of life. On the other hand, students only really are about their needs. So that, as a teacher, their needs are primary at all times. Teaching is a giving profession. That helped to balance me. Part teacher, part artist. It is an age-old equation.

I really admire the way you write and think about your work and the work of others – it feels endlessly questioning and questing, asking questions that might not have answers. You’ve talked in your writing about taking photographs and realizing you couldn’t make sense of what you shot or find logic or cohesion in them, and also about how, at some point in your career, you started to think of your photographs as part of a series. Can you talk a little about how this plays out in the act of taking a photograph? Are you consciously thinking of the photo in relation to others (of yours, or as part of the history of photography)? Or are these connections you make after the fact, looking back on what you shot?

Of course, all the photographs you’ve ever taken are rattling around in your head as you take a new photograph. But isn’t that true of all of us as we grow older? Our past informs and shapes our present. As you grow and learn more, as your knowledge of history enlightens your own work more, you make photographs that reach a little deeper or have more substance.

Photography is immensely difficult to do well, I believe. I have benefited so much from those who have preceded me and learned from a few of the very best.

My heart is in the making of the work, in every frame shot, in every failed and successful image made over now a long career.

My artist statement on the gallery page of my site addresses the facts of my work, what my personal philosophy and aesthetic proclivities are, but doesn’t explain where my heart is. My heart is in the making of the work, in every frame shot, in every failed and successful image made over now a long career. My heart lies in the few successes that I get, the ratio of a few triumphs over so many abject failures that keep me coming back for more.

In wrestling with how to put this into words, Aaron Siskind, one of my teachers, called this “the juice,” and it is the reason we’ve taken on this peculiar and challenging career of making still photographs as art.

See interviews with Neal Rantoul on The Crit House channel here:

Neal Rantoul is a career artist and educator. He retired from 30 years as head of the Photo Program at Northeastern University in Boston in 2012. He taught at Harvard University for thirteen years as well. He now devotes his efforts full time to making new work and bringing earlier work to a national and international audience. See more of his work at nealrantoul.com.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, Photo Essay, photography