By Mike Ladd

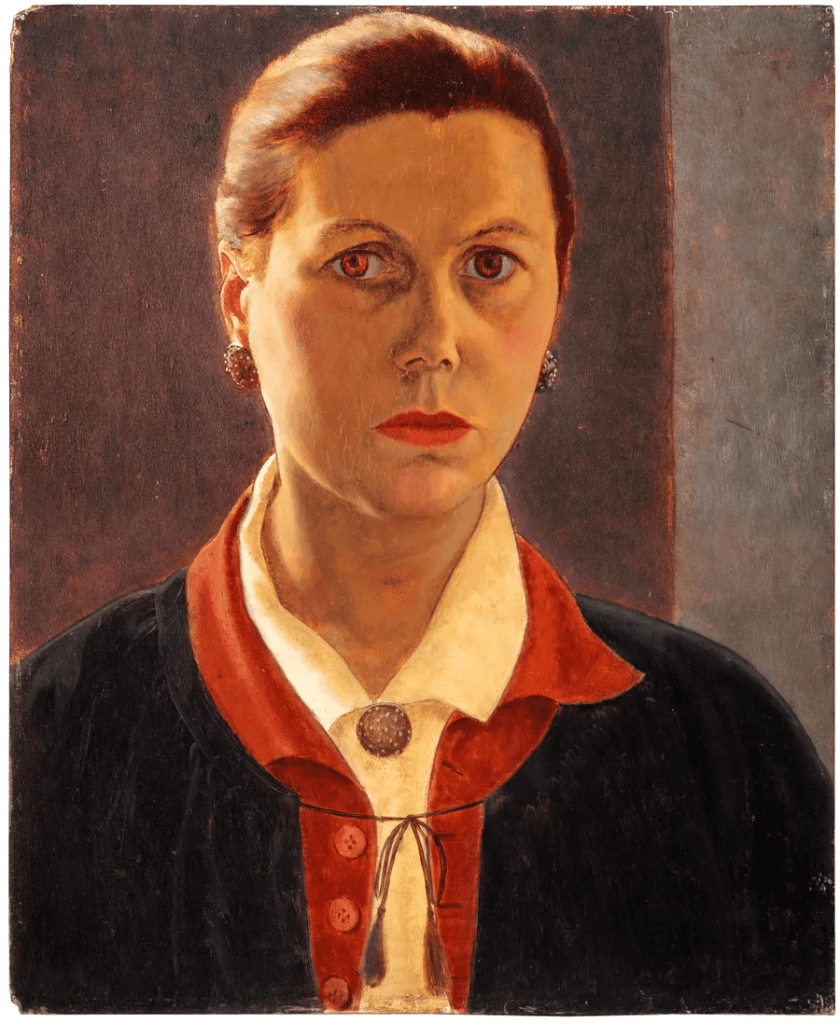

Stella Bowen’s self-portrait in the Art Gallery of South Australia has long haunted me. Something in the intensity of Bowen’s stare always makes me seek the portrait out and stand for a while in front of it, pinned to the spot.

Stella Bowen was raised in upper middle-class comfort in North Adelaide before the First World War. She sailed for England in 1914 and never came back. Studying painting and meeting the novelist Ford Madox Ford, she lived with him in poverty in England and France in freezing farm houses with no running water. She and Madox Ford had a daughter named Julia and settled in Paris where Bowen found herself in the epicentre of modernism; circling round Ford’s newly created magazine The Transatlantic Review, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, and T.S. Eliot all ate at her table.

Bowen painted this self-portrait in about 1928. She had already separated from Ford because of his affairs with other women, including the novelist Jean Rhys. At that time, Bowen was barely supporting herself and her daughter through commissioned portraits and her small allowance from home, the Great Depression was on the way, and she was about to lose her apartment in Paris.

This ekphrastic poem is my response to Bowen’s courageous self-portrait. I imagine her staring both at us as viewers and at herself, looking back on her life and into her own future. Stella Bowen died in England on October 30, 1947. She had wanted to return to Australia, but was denied a pension, or assistance with the passage home. The quoted lines in the poem are from Bowen’s 1941 memoir, Drawn from Life.

Stella Bowen Self-portrait

That enormous right eye

centres the painting.

Lit-up amber, it’s a caution,

a statement about seeing.

Warm light falls on the right side of her face,

a fineness of chestnut hair –

I could almost place my hand

into the picture

stroke that hair just above her temple

knowing exactly how it would feel.

Her stare unsentimental,

she remembered her hometown:

‘a queer little backwater of intellectual timidity,

prettyish, banal and filled to the brim with an anguish of boredom.’

Mills Terrace, North Adelaide.

Tennis and roses, church and servants, and heat.

*

Now I imagine she’s not looking in a mirror

but at me, her viewer.

She’s just caught me fudging the truth

or stuck in some small-mindedness.

I am judged

and found wanting.

But I turn the gaze back to its real subject,

the gazer herself.

Anger tightens her jaw.

Is she thinking of lost time,

how she demoted herself

to housekeeper for Ford Madox Ford,

her painting pushed back behind his novels

while she cooked and dealt with the bills?

Is she thinking of his new, younger woman

taking her place as she once took another’s?

Now she stares into the face of the Great Depression,

thirty-six years old, a daughter to support

her life in Paris disappearing

with the exchange rate.

She sees the rise of the dictators,

her old friend Ezra spruiking Mussolini.

She sees how she must hawk herself

doing family portraits of the rich who are still rich –

but this one

is just for her.

She looks hard into the future:

a Second World War, survival in England,

perhaps all the way to her own death,

not enough money in the bank to come home –

finally wanting again the ‘sky almost empty of blue’

‘the yellow ochre of the dried grass.’

Mike Ladd is a South Australian poet, essayist and nature lover. He has published ten collections of poetry and prose, including the natural history Karrawirra Parri, Walking the Torrens from Source to Sea, from Wakefield Press. His most recent book is Dream Tetras (2022) an experimental collaboration with visual artist Cathy Brooks. Mike was the editor of ABC Radio National’s Poetica program, which ran for eighteen years and brought Australian and international poetry to a wide audience. His new book Now-Then, New and Selected Poems has just been published by Wakefield Press.

Categories: art, featured, featured poet, poetry, why I love