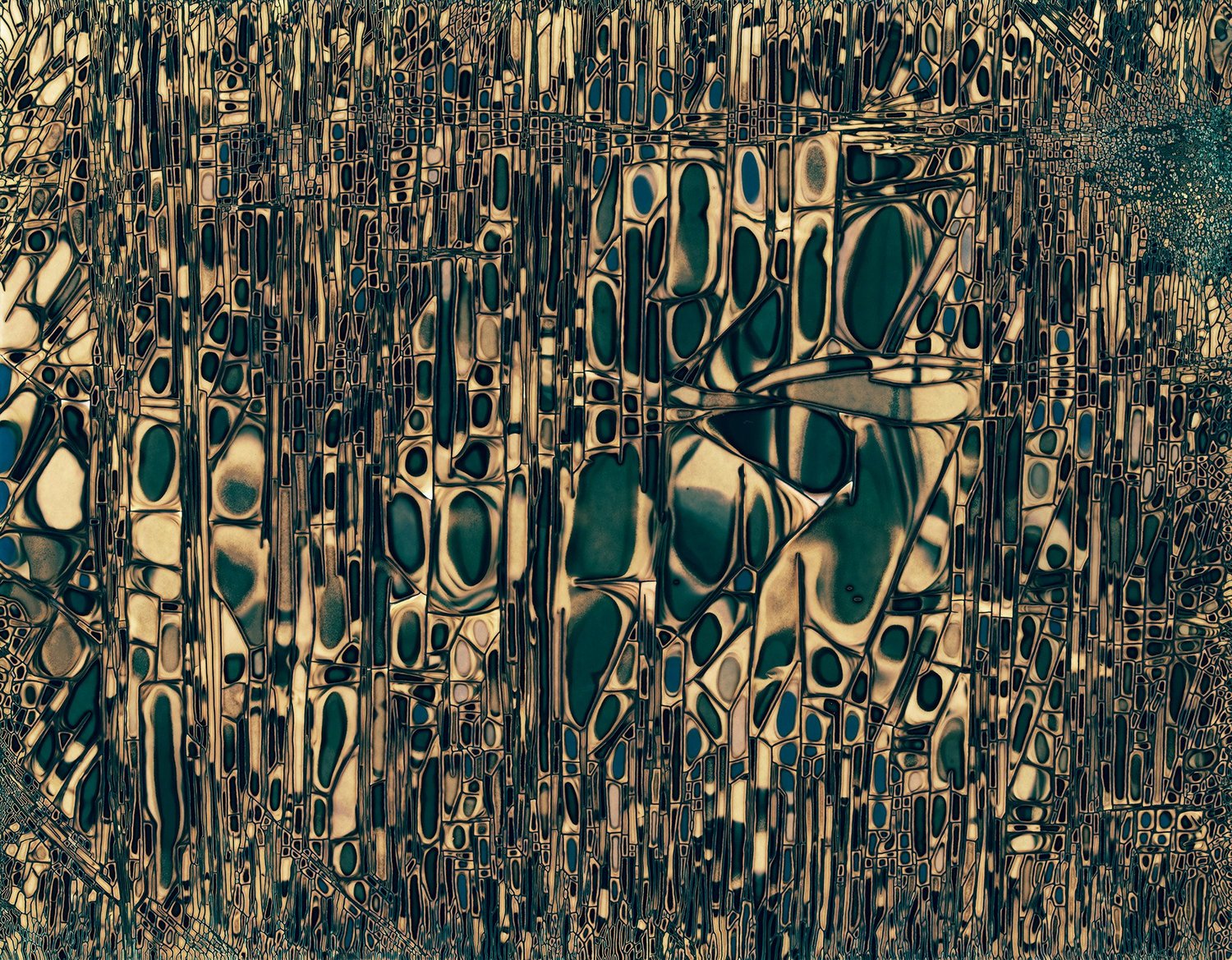

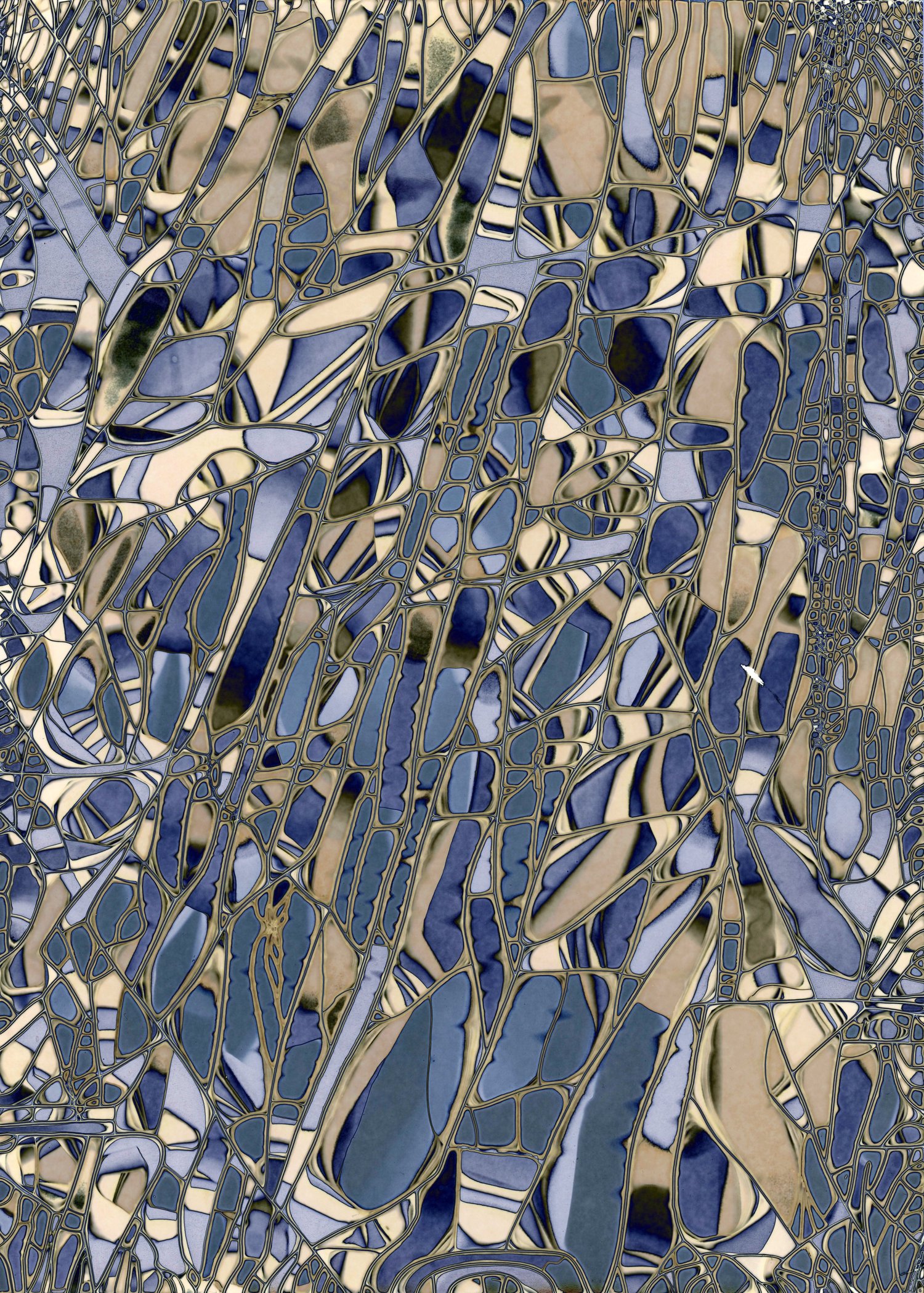

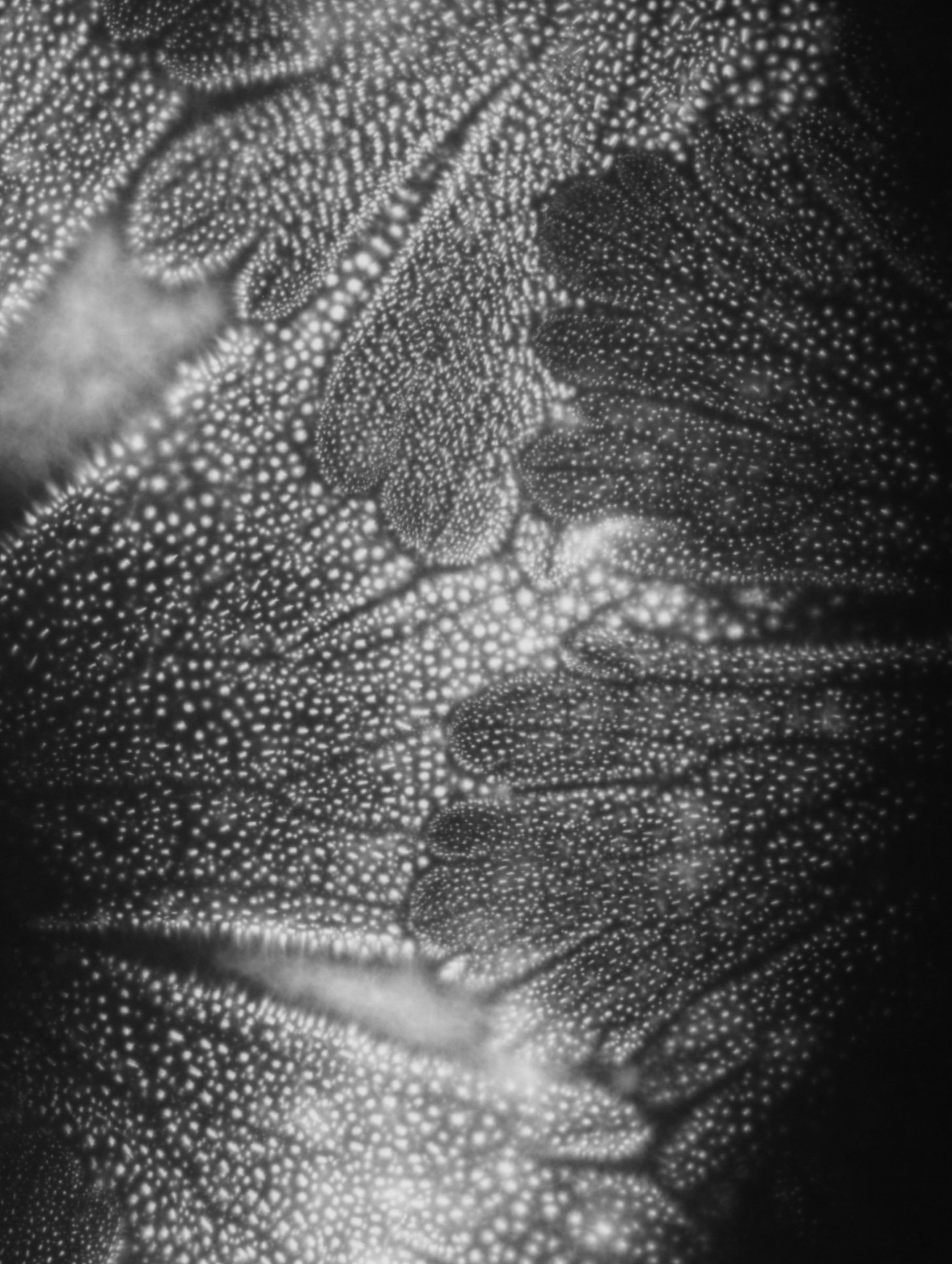

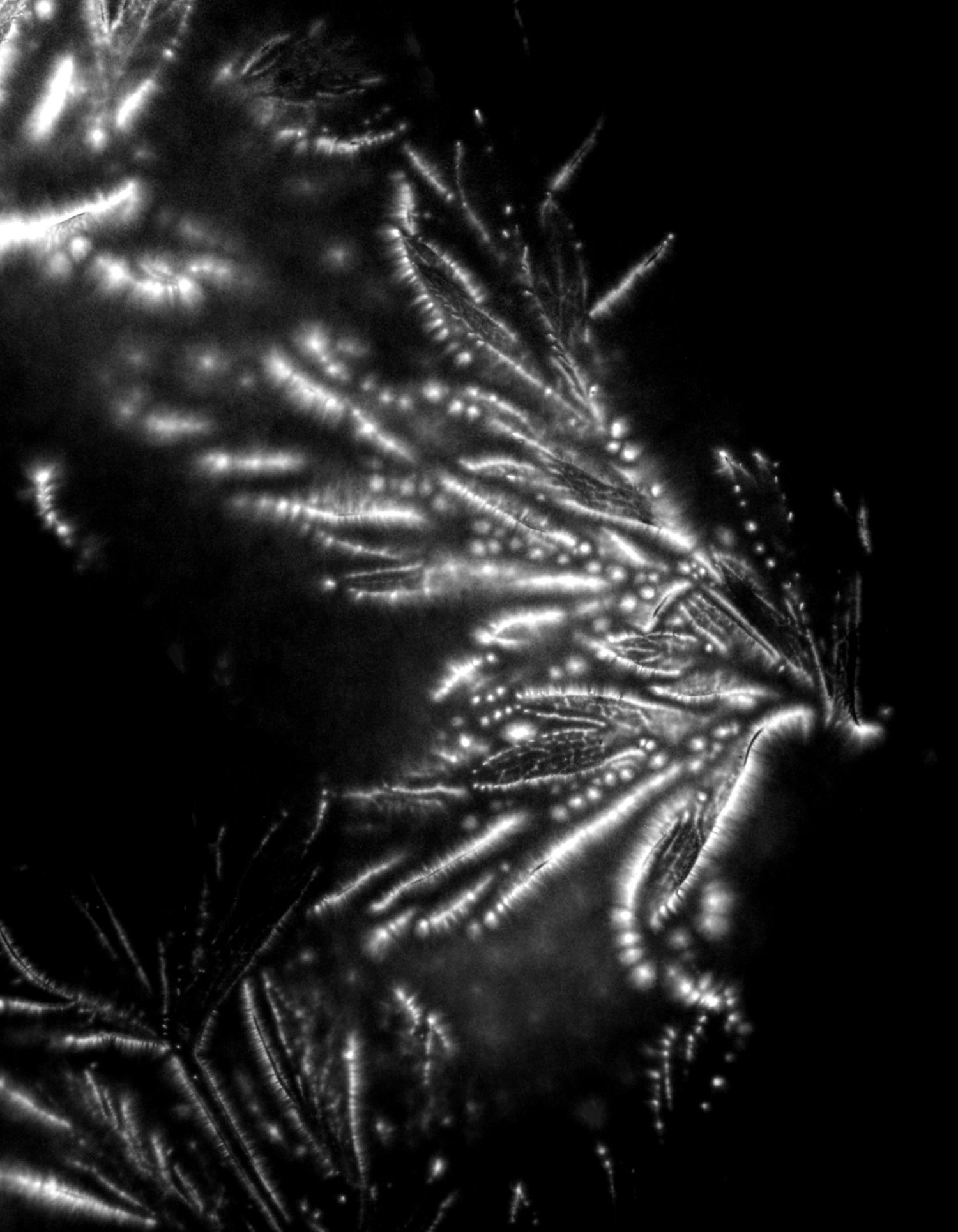

Photographer Paula Pink uses alternative processes to show us an alternative view of the world. She employs photographic techniques — with and without the camera — to reveal a different way for us to understand nature, memory, and the patterns and connections that bind us to each other and to the universe. Her images are moving on many levels, shifting fluidly from now to always, here to everywhere, one thing to everything: From a bright clarity to the murky depths of things beyond our understanding. We can’t understand them, but we can ask questions, and we can appreciate the beauty of not understanding. We were grateful to have a chance to ask Pink a few questions about her work.

Magpies: You say that you listen to music as you work, and that it dictates the rhythm and tempo of the process. I’m curious about the music you listen to and what you find inspiring. Do you choose a certain song or album depending on the work you want to make that day?

PP: I usually begin my work in silence, focusing purely on the intention for the day and what I’m trying to explore or figure out. I need a sense of calm and quiet to gather my thoughts and get organized. But with a process like making a chemigram, which can take many hours — sometimes a whole day — my mind eventually starts to drift, and that’s when I’ll look for music to accompany the work.

Often, I’m not even fully aware of what’s playing; it simply becomes part of the background. The same goes for when I’m in the darkroom, which is already a very quiet and contemplative space. After a while, it’s comforting to have sound around me – it helps me settle into a rhythm and find my flow.

Today, for instance, I was thinking about erosion — both as part of the artistic process and as a metaphor for broader events in the world.

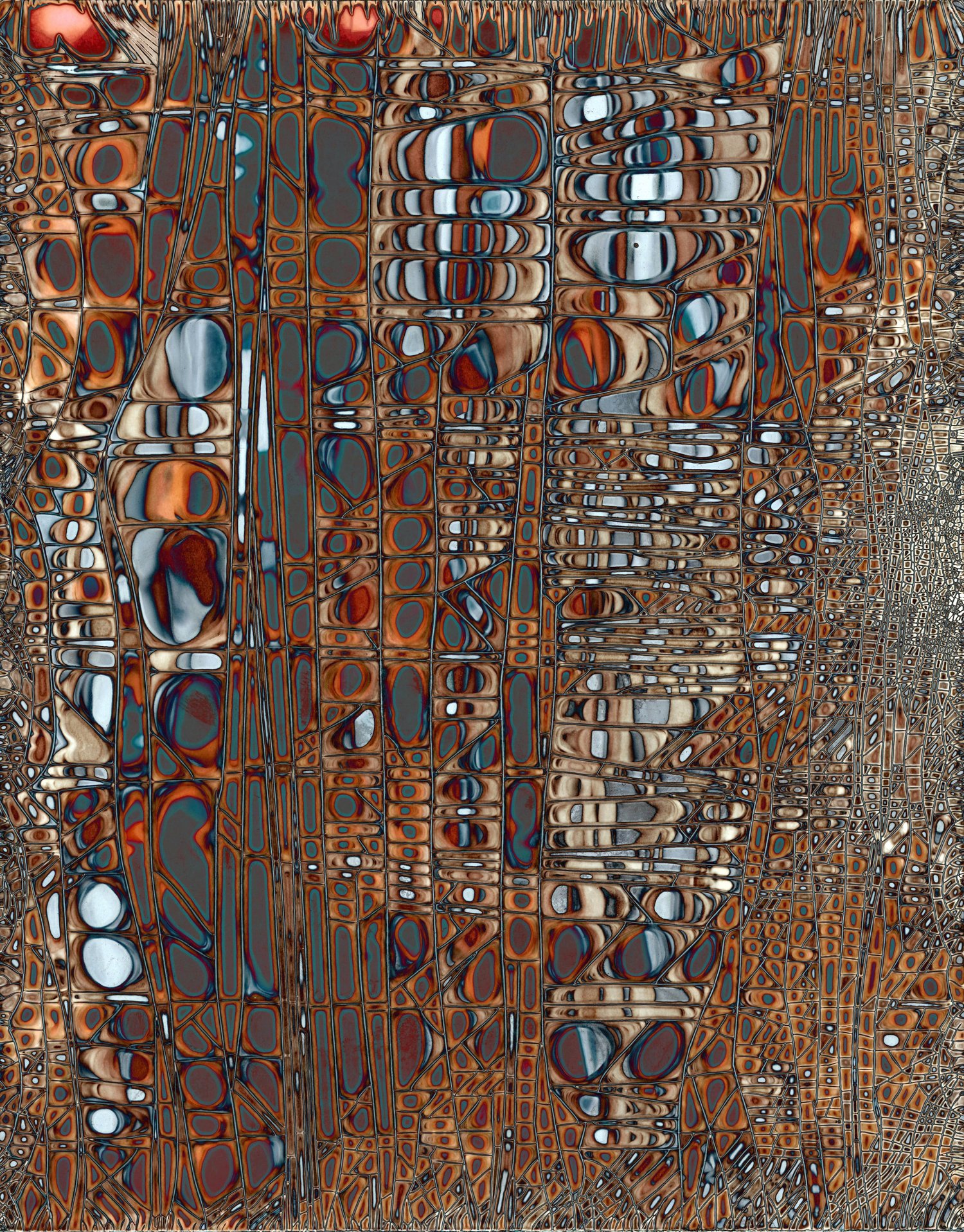

Today, for instance, I was thinking about erosion — both as part of the artistic process and as a metaphor for broader events in the world. As the image took shape, I began looking for music that reflected this kind of mood. I came across Philip Glass’s Glassworks, which seemed appropriate — the repetitive structures and slow shifts feel very connected to the gradual, transformative nature of erosion. There’s a meditative quality to his music that mirrors how time and pressure shape both materials and meaning in the work.

Related question: I’m wondering about the process of making the watergrams and chemigrams. It feels like there’s so much you’re controlling and so much that’s beyond your control. When you describe the rhythm and tempo, are you speaking of the movement of the fluid, the light, the chemicals, the papers, and the processes? Is there some balance between an idea of what you want to create and a sense of letting go and seeing what appears? I feel like with photography, there’s always a push and pull between capturing an image and creating it, and I’m curious how that plays out in your work.

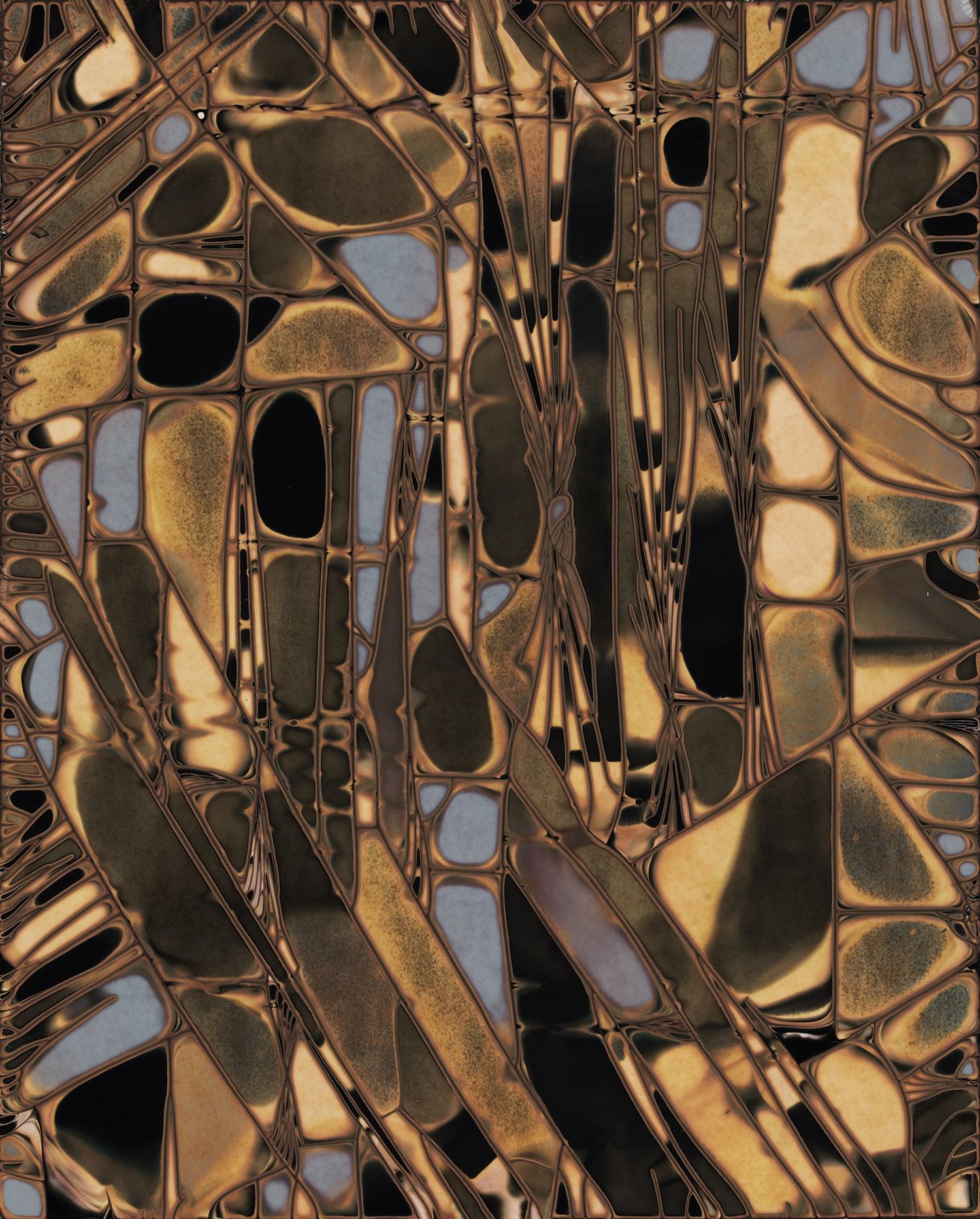

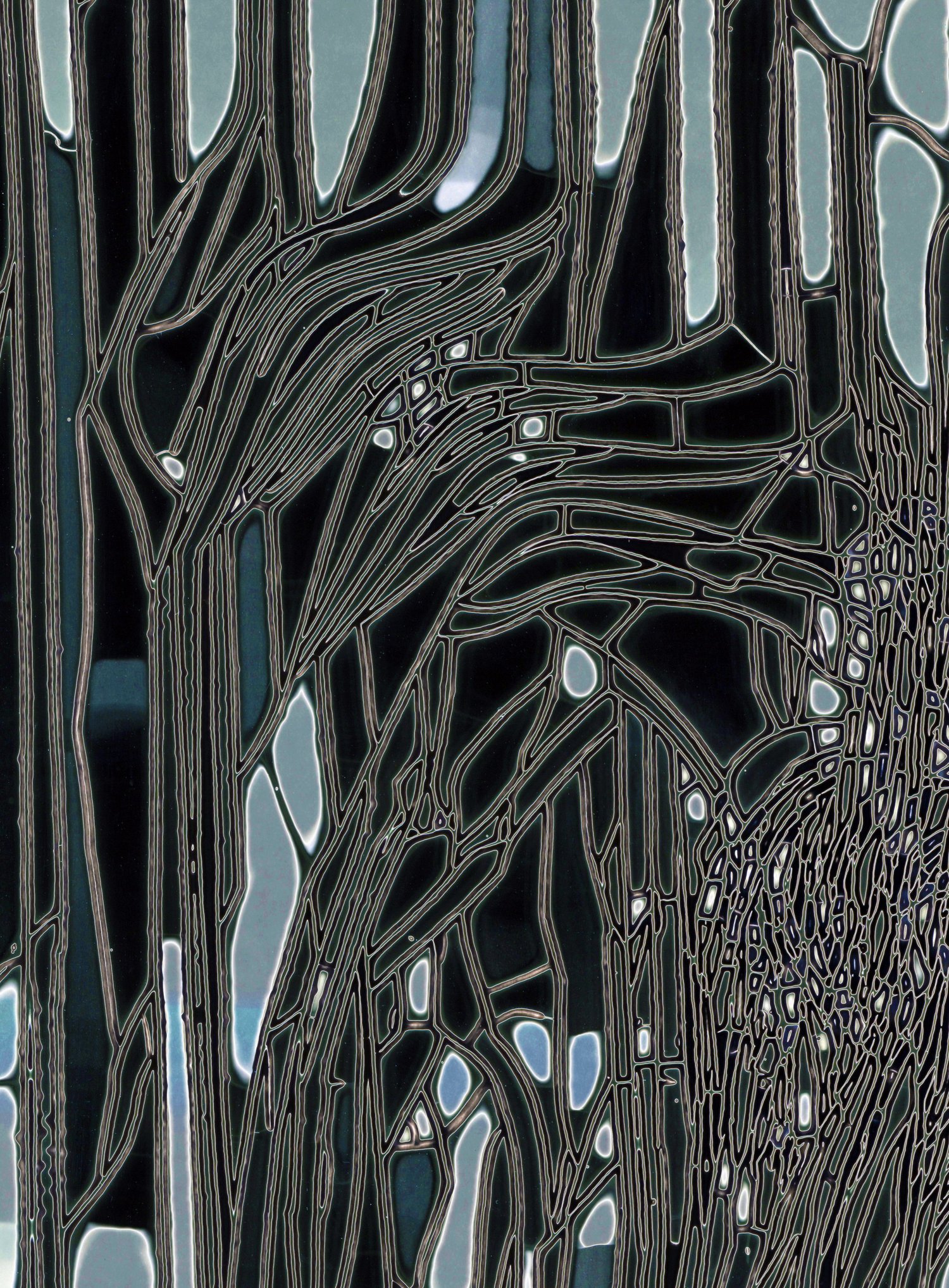

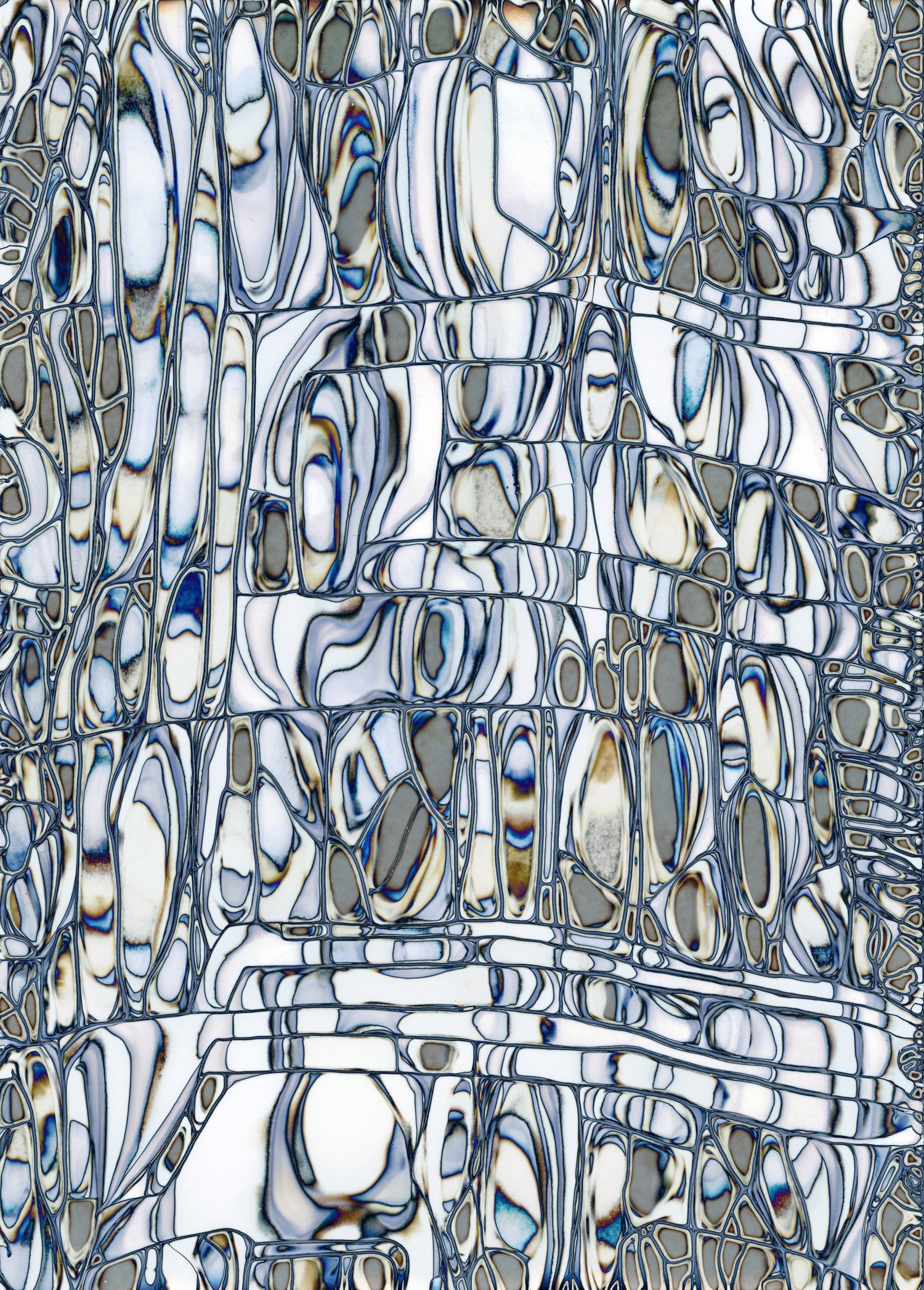

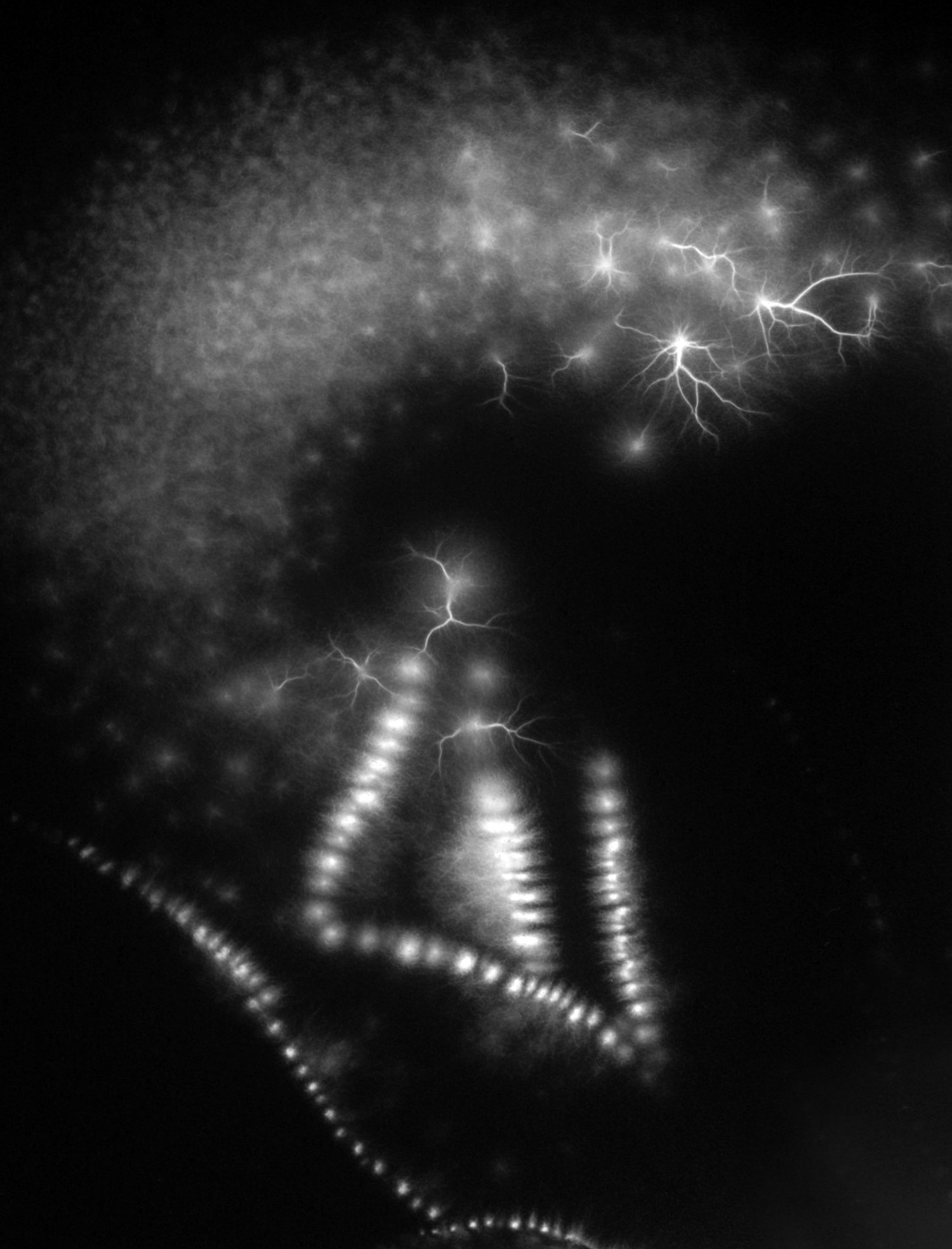

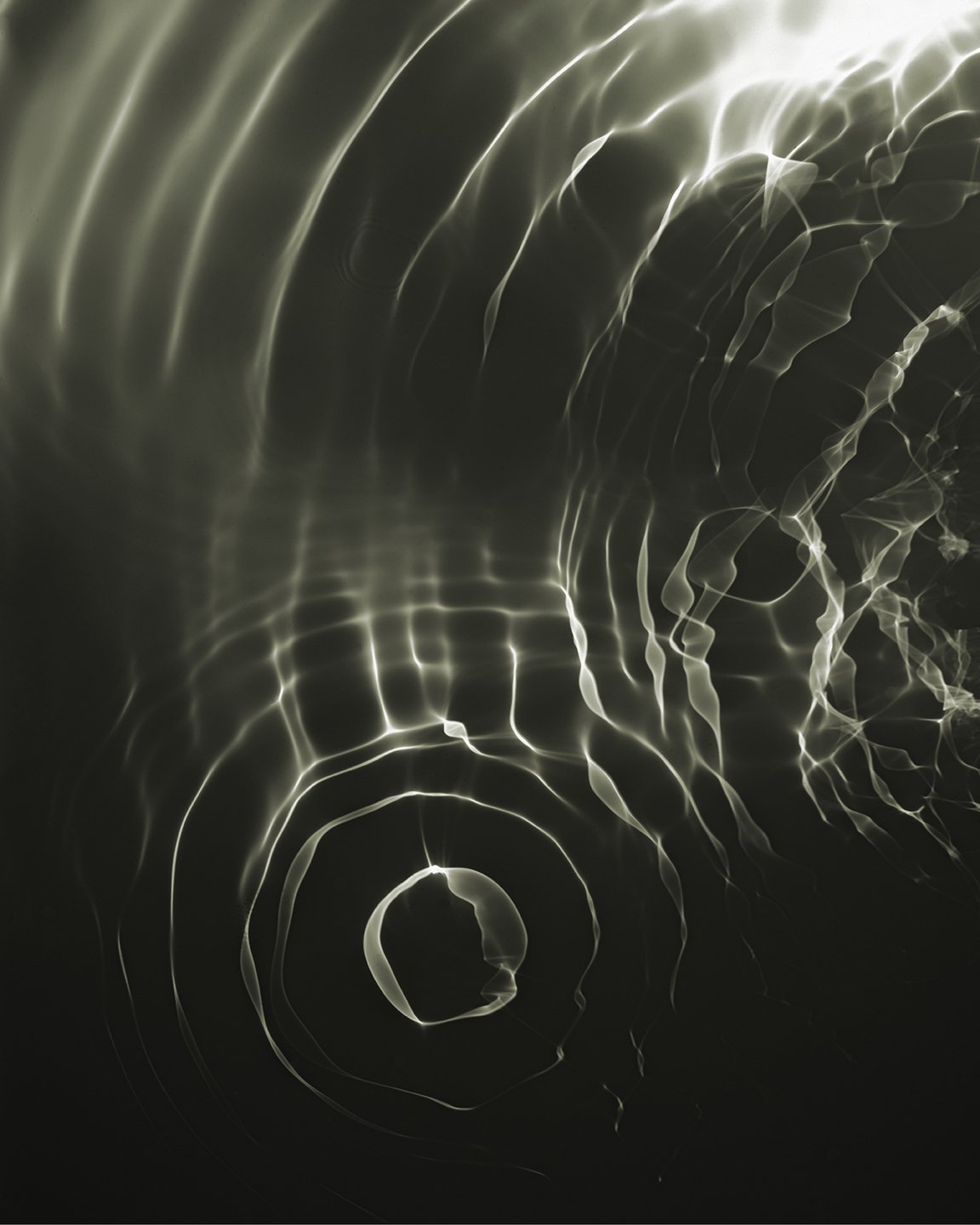

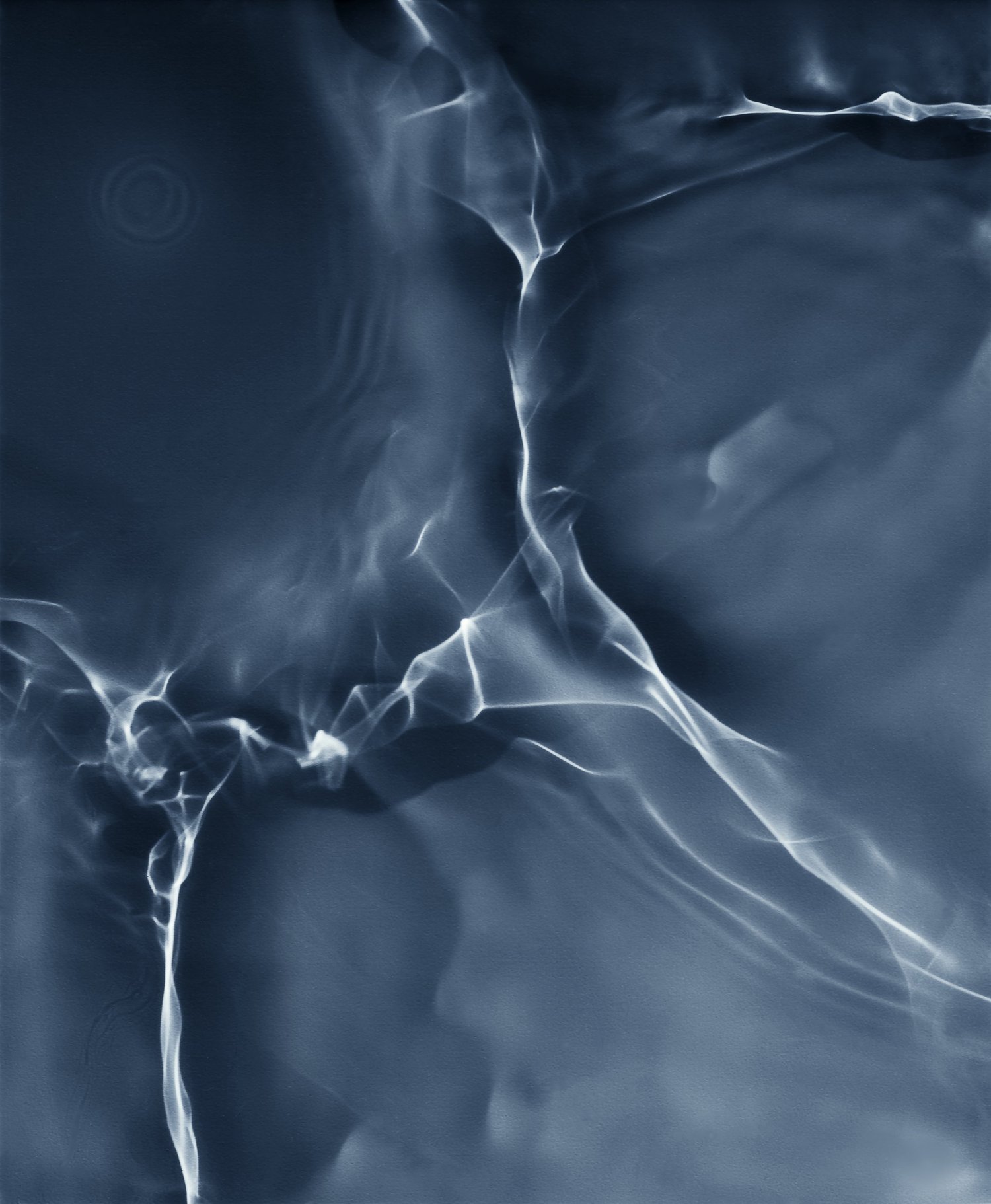

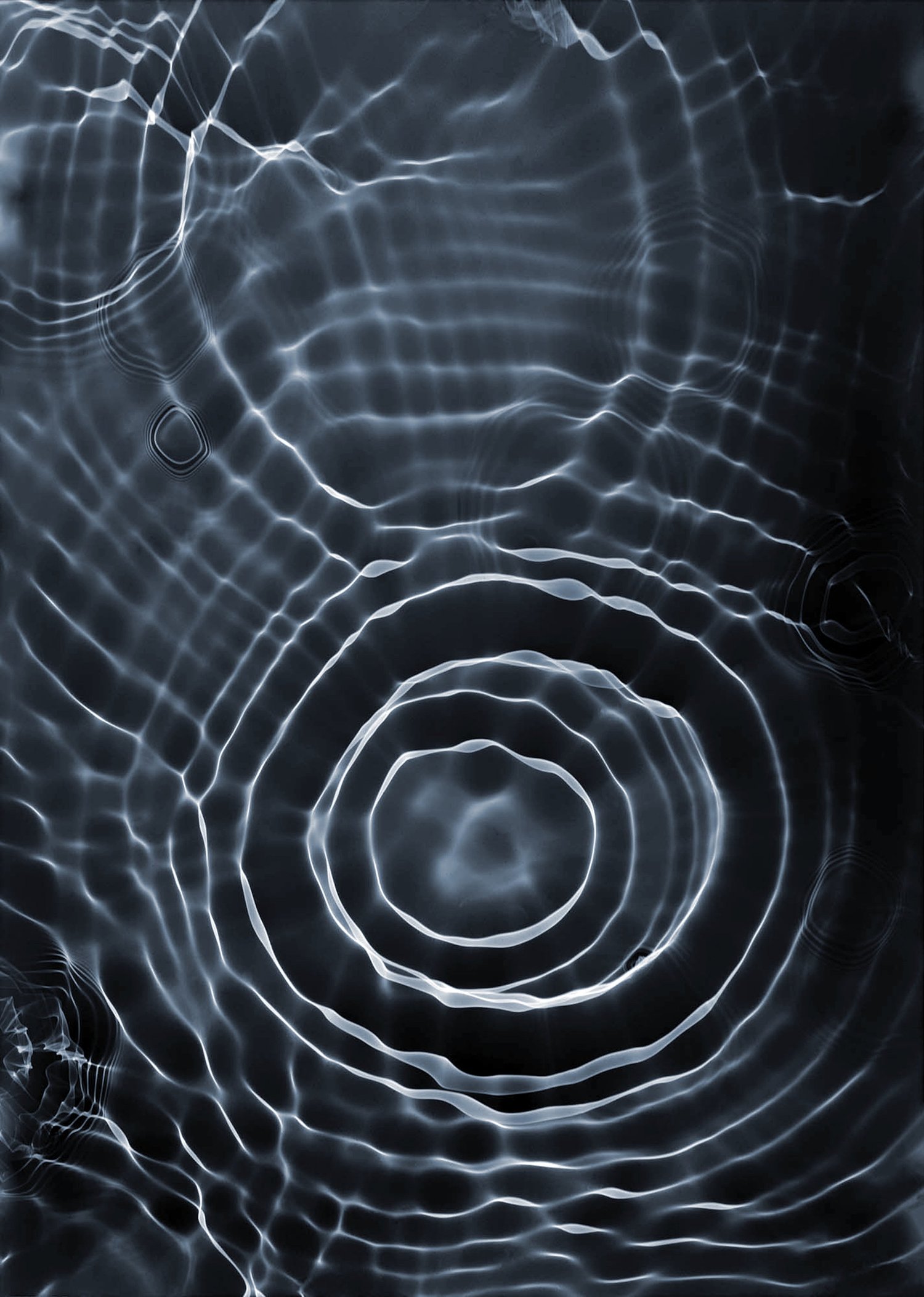

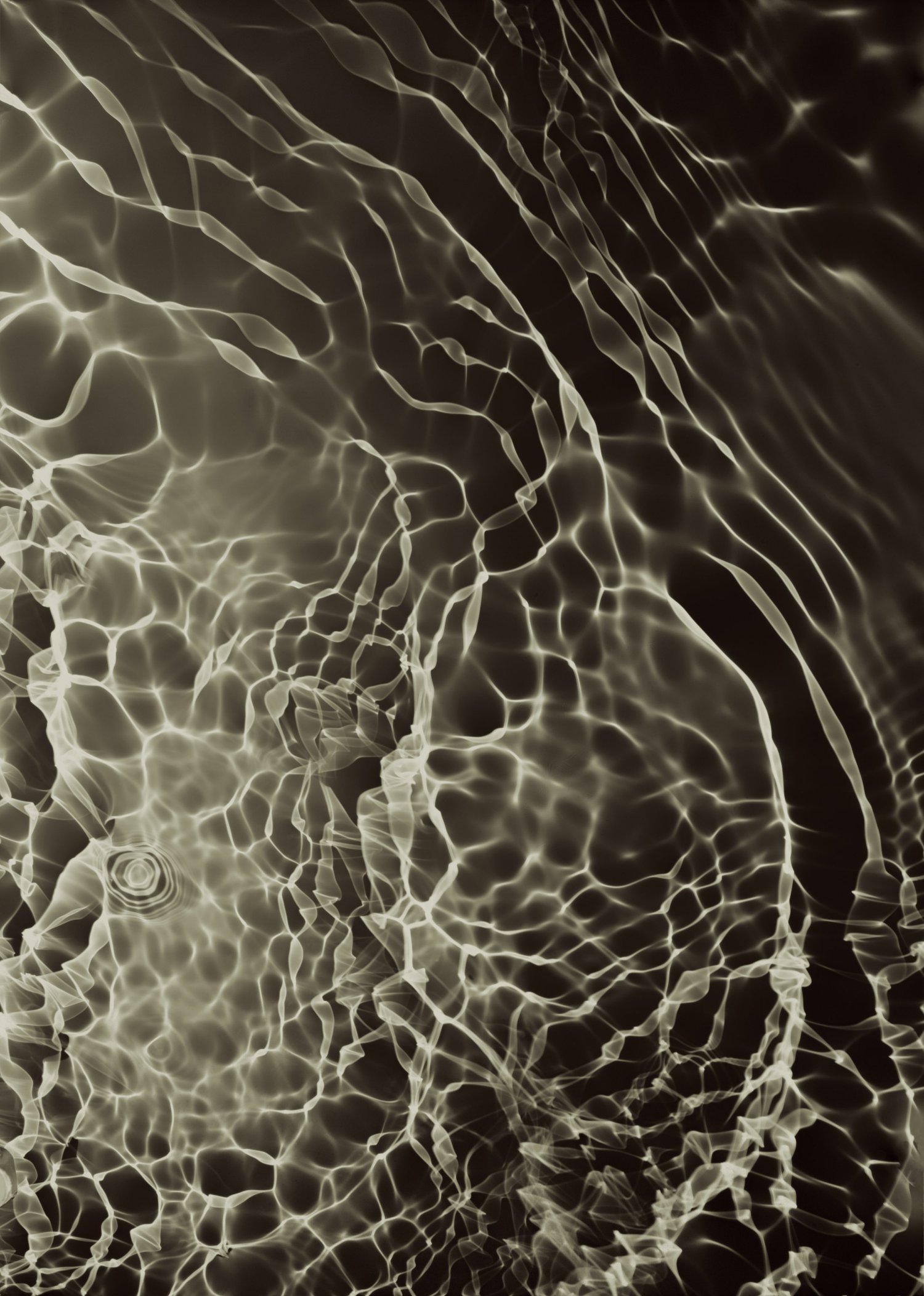

There is a difference between the process of making watergrams and chemigrams, but both involve elements of chance and control. There are things I can guide, like choice of paper, chemicals, lighting, how and where I introduce water or resist, and timing etc. But there’s also a great deal that’s unpredictable — how the chemicals react in that moment, how the paper performs (particularly if it is expired paper), how light and fluid move on the surface.

When I talk about rhythm and tempo, I think I am referring to all of those moving parts: the flow of liquid across paper, reaction times of chemicals, whether I’m working quickly or slowly, methodically or intuitively. There’s a kind of pacing and responsiveness that feels physical and instinctive, like choreographing with physics and chemistry perhaps.

I’m not just capturing light, but also the very chemistry of transformation.

There’s definitely a balance between intention and spontaneity. I often begin with a loose vision or feeling for I want to explore, although there is no fixed outcome and I try to remain open to the process, to what the materials want to do. Some of the most interesting results come from letting go of strict control and allowing the piece to evolve organically, to capture fleeting moments of reaction while also creating something unexpected and new. So yes, like in more conventional photography, there’s a push and pull — between documenting a moment and generating one. But with watergrams and chemigrams, that tension becomes more physical and temporal. I’m not just capturing light, but also the very chemistry of transformation.

I’m fascinated by your use of expired photo paper. I love the idea of taking advantage of a seeming flaw, and this also seems like one way to tip the balance towards chance rather than control – are there other methods or materials that you employ to add that bit of unexpectedness to your work?

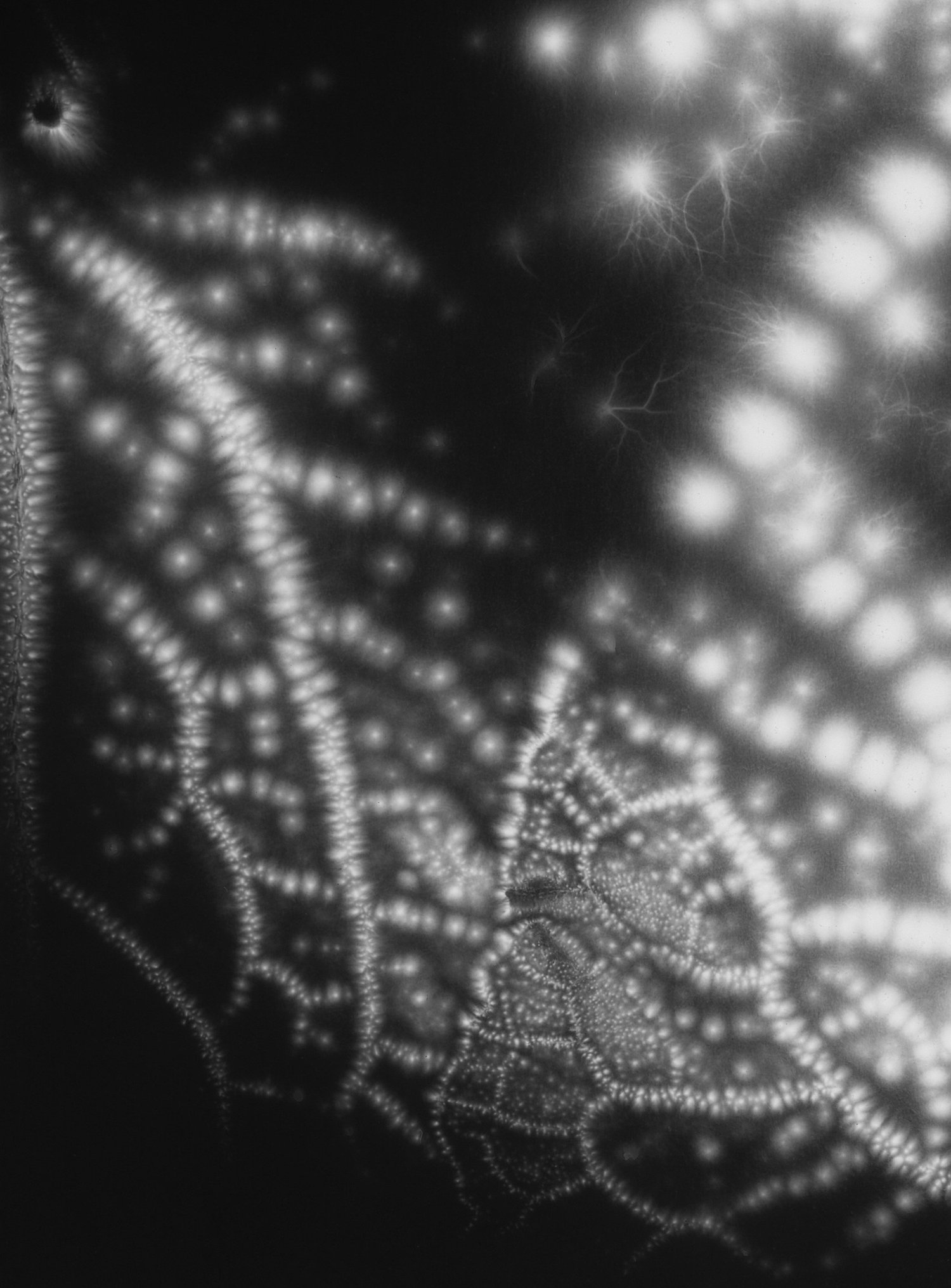

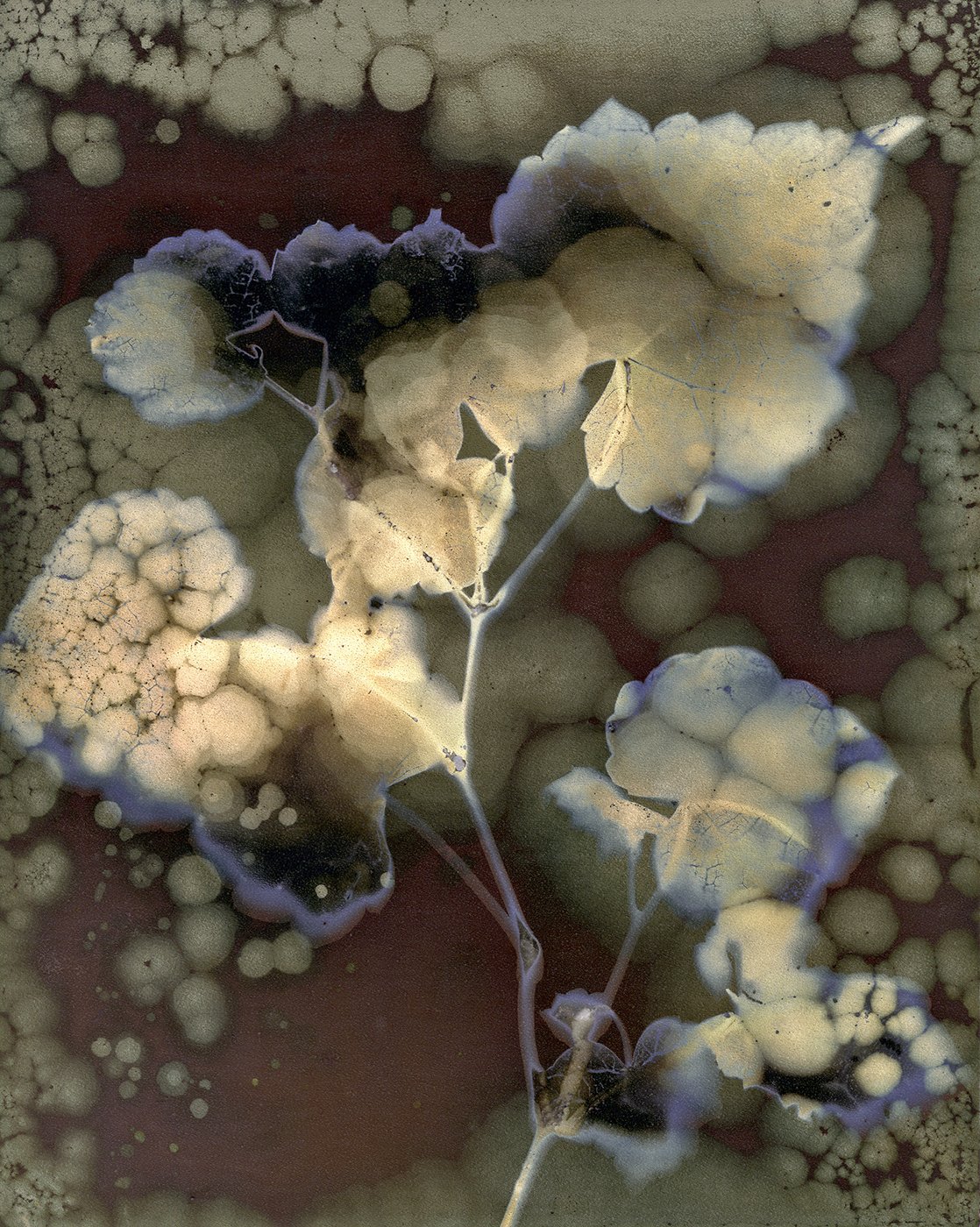

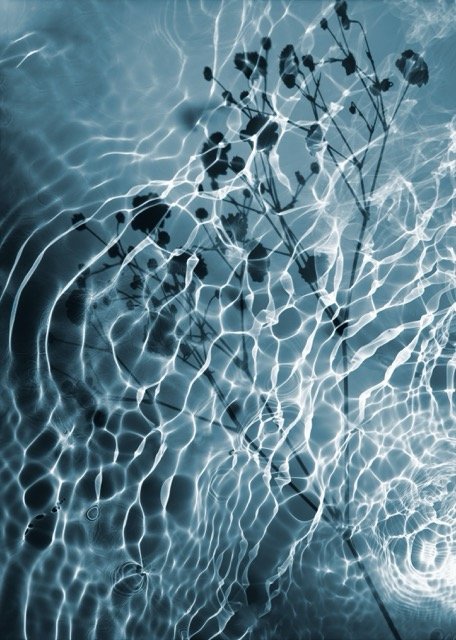

I first began learning about alternative photographic processes by making lumen prints using expired photo paper I bought inexpensively on eBay. Many of these older vintage papers have a higher silver halide content, which makes them more sensitive to light — and that sensitivity often creates unexpected and intense color shifts when exposed to the sun. That unpredictability is part of what makes the images all the more fascinating and elusive. The same kind of thing happens with chemigrams or chemi-lumens: using expired paper and experimenting with different resists (varnish, oil, household sprays) adds more layers of chance and unpredictability. I love how the materials seem to take on a life of their own — it feels like they’re active collaborators in the process. For me, it’s not just about how the final image looks, but about exploring the materials themselves and how they behave. It’s a way of shifting the focus from a purely visual aesthetic to something more material and process-driven, allowing the inherent characteristics of each element to guide the visual outcome. I will add that these papers are becoming increasingly rare, and so I feel less frivolous, (and hopefully more intentional), about experimenting with them than I did at the beginning!

I’m a longtime believer in the idea that everything is connected on some level that humans will never understand, though we like to think of ourselves as being so savvy about everything around us. So much about your work seems to be exploring deep, recognizable, but very rarely visible connections between the inner and outer patterns of all life and the universe. The cells in a leaf or in our body, the sparks of energy flowing through our bodies and through the universe. I wonder how much you’re creating the images, and how much you’re revealing and recording a visual representation of a universal truth. Illuminating it, literally, since you’re painting it with light.

That’s a lovely question, and one that resonates strongly. I think photography — and art in general — has the ability to connect us on a deeper level than we experience in our everyday lives. I believe we have been conditioned to think more with our brains (mind) and have increasingly forgotten how to feel with our instincts and our gut — genuine feelings that reflect real inner experience — so working with the photographic materials I have been experimenting with recently (and connecting to nature) leads me right to those ideas about connections. I strongly believe that the process itself — if I am truly engaged with it — will always uncover an element of life’s mysteries or reveal some hidden truth that has gone unnoticed / unrecognized for me up until that moment.

I imagine the process of uncovering and recognizing these patterns must be thrilling. Are you generally alone in the dark as they emerge? I imagine it’s a very profound experience, raising and answering a million questions that can’t really be answered. Does photography help you to feel a part of this web of connections?

The process of making a chemigram is shaped by the same forces that sculpt mountains and curve valleys, and those same physical rules that guide the formation of an image can, under different conditions and timescales, govern the evolution of entire landscapes.

I am usually alone when I work, though not always in the dark. However, whether I’m working with chemigrams, or lumen prints, or in the darkroom, I’m immersed in a dialogue with the materials and matter around me. I see the process as a collaboration with light, chemistry, and time. Often, a microcosm of the earth’s surface and structure will emerge, with shapes and forms resembling vast geological formations, branching patterns, jagged edges, that look strikingly similar to mountain ranges, river systems, striations on a shell or weathered stone. Science tells us this resemblance is not merely coincidental — it reflects shared principles of growth, erosion and pattern formation found throughout nature. The process of making a chemigram is shaped by the same forces that sculpt mountains and curve valleys, and those same physical rules that guide the formation of an image can, under different conditions and timescales, govern the evolution of entire landscapes. I find that fascinating!

I believe, as humans, we can never really understand the workings of nature, which we’re a part of, though we like to think of ourselves as separate and better. And we sometimes (especially lately) seem to be doing our best to tear away and destroy the natural world. Your work is fundamentally about nature on so many levels, in all of its mystery and beauty. To what extent do you think about sharing a kind of message or warning about the precarious state of things, even just by making them visible and recognizable?

I think it is important to find any angle that creates space for open dialogue and to encourage new ways of seeing and understanding the world around us. There is so much about our contemporary world that we are unaware of, and I think it is important for us all to share our ideas so that we have a better understanding about what connects us and divides us. I also think it is really important for young people to have hope, and so I try to emphasize a certain beauty and wonder in my work and make a connection to nature in that way. It won’t appeal to everyone, but hopefully it will resonate with some. I think there are many angles for us all to encourage a deeper connection to one another and the world around us.

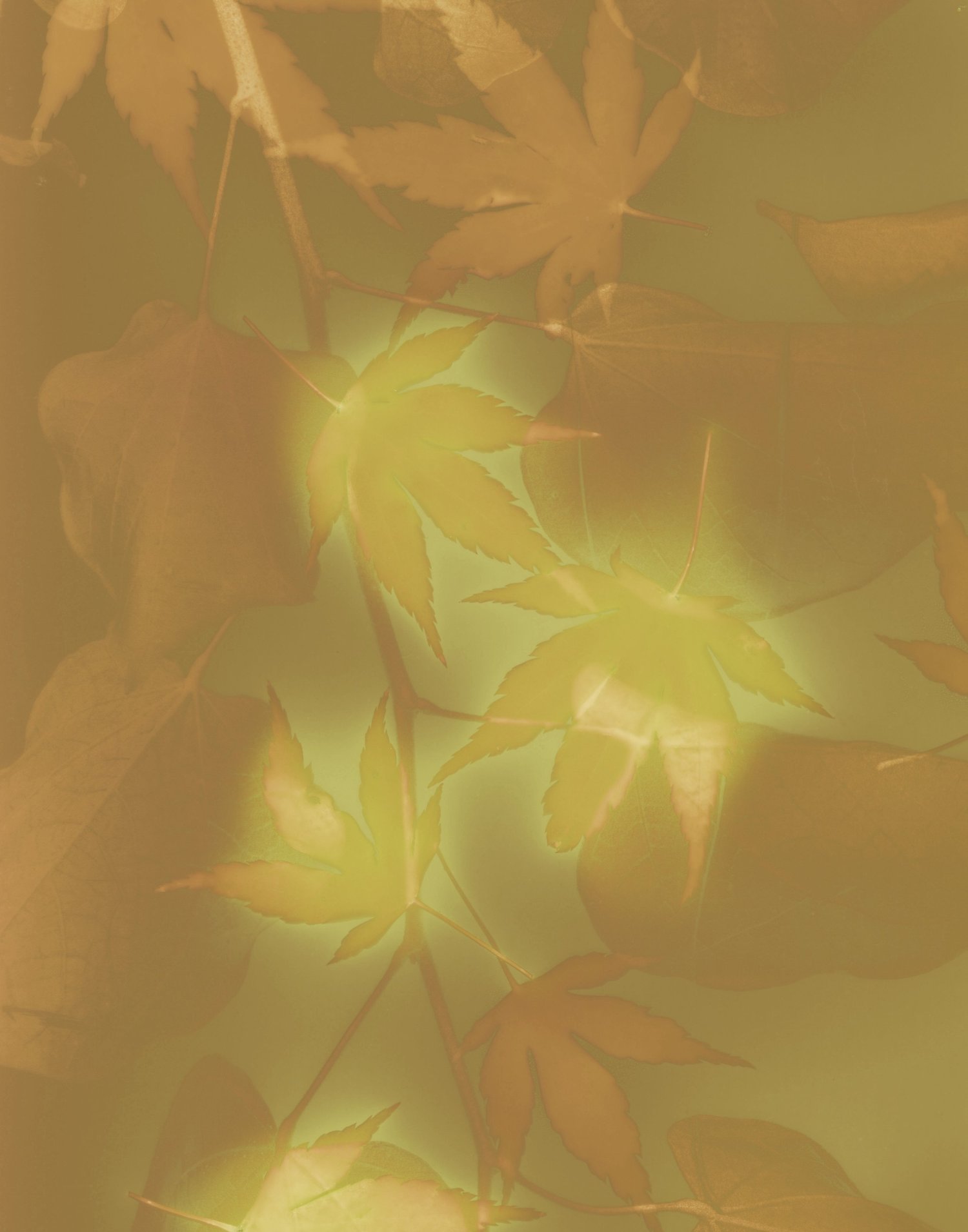

I love your lumens series – it reminds me of the early cyanotypes of Anna Atkins, which are such an almost ghostly representation of leaves and flowers. Since it seems like a lot of your creative work is done in the darkroom, I was thinking about the the part of the process that involves gathering natural materials to work with, and wondering about parts of your creative process that occur outside of the darkroom – I imagine it varies according to each type of work that you create.

Thank you! Lumen printing, as I mentioned, was my first foray into experimental photography, and I love that it is done in the “light’ for the most part. It can be a welcome change. I love that the chemistry, the heat, the humidity, the strength of the UV rays all play a part in creating these “ethereal” images alongside natural (more solid) materials. It is important for me to connect with nature daily, usually on a morning walk where invariably I’ll find something that piques my interest — the pattern on a leaf if I’m in the woods, or a branch from a tree overgrown with moss, or the time-worn lines tracing the surface of shells or coral fragments if I am at the beach. Sometimes I go with a clear intention of what I am looking for depending on the process I am working with, but mostly I get lost in thoughts, ideas, new themes, and all my planned intentions go out the window! I will admit I am not particularly organized, and I usually have a million ideas and unanswered questions floating around in my mind.

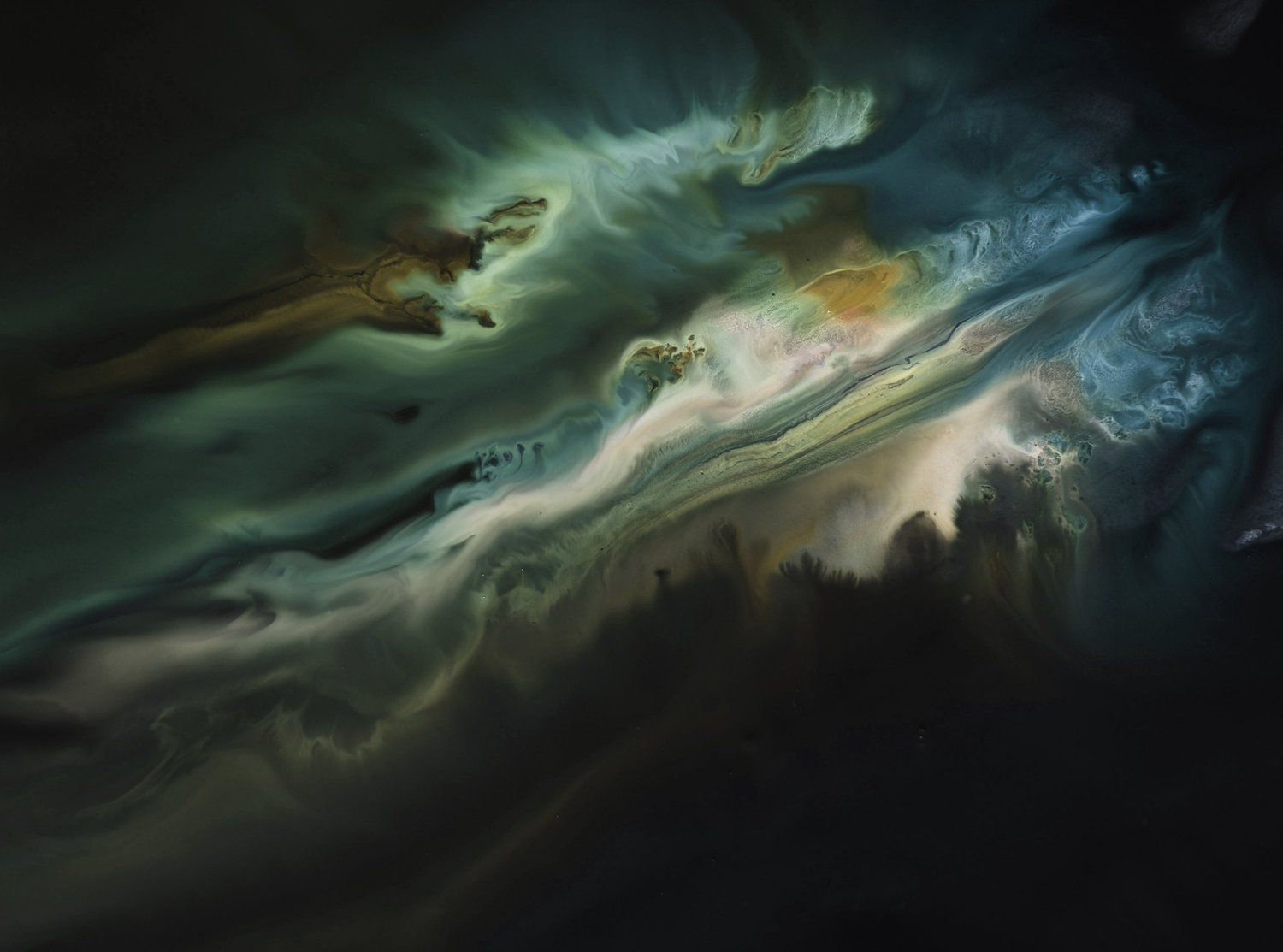

For many, taking a photograph is a way of capturing a moment or preserving a memory. In your work, particularly the watergrams, I’m very moved by the sense that you’re capturing not a specific memory but something more universal. Fundamental memory rather than nostalgia. For me and I imagine for many others, my memories are often reflected in water – creeks, rivers, ocean waves, rainy days. This got me thinking about just how watery memory is, clear one moment, cloudy the next, still or troubled. How do concepts of memory play out in your work?

I am not trying to fix a memory in place like a traditional photograph might. Instead, I’m chasing the feeling of remembering — the way memory behaves more like water than stone: slipping away, returning, changing shape depending on the light or tides.

I think memory, like water, can never be static. It shifts, flows, evaporates, returns. To me, there is something poetic about that thought that hopefully resonates with my images. I am not trying to fix a memory in place like a traditional photograph might. Instead, I’m chasing the feeling of remembering — the way memory behaves more like water than stone: slipping away, returning, changing shape depending on the light or tides. My watergrams are not literal images, they are sensory impressions, like, as you suggest, the way a childhood creek might shimmer at the edge of consciousness.

When we lose our connection to nature — when we no longer have those tactile, sensory experiences of being in water, under trees, in weather — it’s not just the present moment we lose, it’s a language for memory itself. For many of us, the natural world is where foundational memories are formed — quiet moments by a river, the rhythm of waves, the smell of wet earth. Those are not just background settings; they are emotional landscapes we return to, even unconsciously. When we’re distracted from nature, those touchstones fade, and with them, a part of how we understand ourselves and our past. The watergrams, in some way, attempt to hold space for that — not as literal documentation, but as sensory echoes of something that might be lost or fading, but deeply felt.

Paula Pink is a photographic artist living and working in Charlotte, North Carolina. Originally from Edinburgh, Scotland, she trained and worked as a graphic designer in London and holds a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from The New School, NYC. Her work has appeared in national and international exhibitions and is held in private collections worldwide.

Inspired by patterns in nature, organic forms, and the interconnectivity between living things, Pink’s creativity is diverse, exploring alternative and experimental photographic processes with and without a camera. With light and chemistry as integral co-creators, her work pushes conventional boundaries of the photographic medium collaborating with unseen forces that shape the world around us. Her work invites viewers to contemplate the wonders of nature and its fragile yet essential place in our lives. See more of her work at Paula Pink Photography and on Instagram at paulapinkphotography.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, photography