By Lindsay Steel

A brief introduction to the work of one Britain’s finest (and under-appreciated) landscape painters

At the end of February, I caught the train up the west coast of Cumbria to visit the Sheila Fell retrospective at Tullie House (or Tullie as it is now known) in Carlisle. The journey up the coast is stunningly beautiful all the way to Maryport, and it is one of those journeys that is worth taking just to sit and gaze out of the window.

I’m not sure how well known Sheila Fell is outside of Cumbria, but I suspect that the majority of people will be unaware of her work. She has, for reasons unknown, not been mentioned (as far as I am aware) in any of the books about women artists published in the last few years. To me, this feels a little unjust—her paintings sold well, her work was well received by major art critics, and she was one of just a handful of women (at the time) to become a Royal Academician.

Sheila Mary Fell was born in the small Cumberland1 town of Aspatria on the 20th of July 1931. The family lived in a tiny terraced house surrounded by fields of cows, barley and potatoes, and distant views of the fells2 of the Skiddaw range. Aspatria was a coal mining town, and in sharp contrast to the more scenic views, there were chimneys, slag heaps, and headstocks.3 The daily views of Fell’s childhood heavily influenced her art throughout her tragically short life.

“Farm carts, ricketing past the house, full of hay or turnips, and cows threading their way from milking sheds to grazing fields; and then in the soft black evenings…everything silent except for perhaps the moaning of the wind blowing from the sea across to the mountains and the stirring of cattle in the barns.” Sheila Fell

Fell excelled in art and music at school, and her art teacher encouraged her to apply to Carlisle School of Art,4 where she ended up studying for two years. After this, she seemed determined to escape the sleepy, rural life of Aspatria, and went on to secure a place at St Martin’s School of Art in London to study drawing and painting. Pop art was very much in vogue during her time at St Martin’s; however, Fell had little interest in it and was instead drawn to the techniques of Honoré Daumier, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent van Gogh.

Although she loved her new life in the capital, she realised how much she also loved the village that she grew up in (she never referred to Aspatria as a town), and her feelings of homesickness led her to begin painting scenes from her childhood. Once she had started, she never stopped. Although Fell lived in London for the rest of her life, she would return to Aspatria three or four times a year to visit her parents and make sketches (there is a link to a video of her at home in Cumberland below).

“Cumberland is very dark, but being dark it is also brilliant.” Sheila Fell

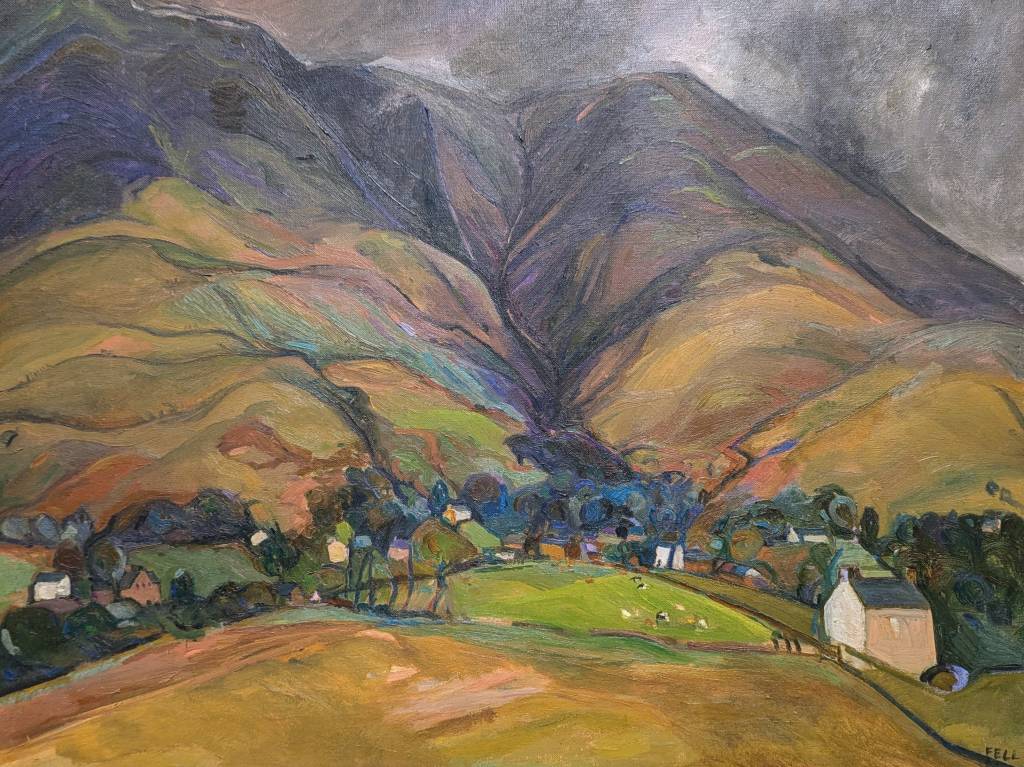

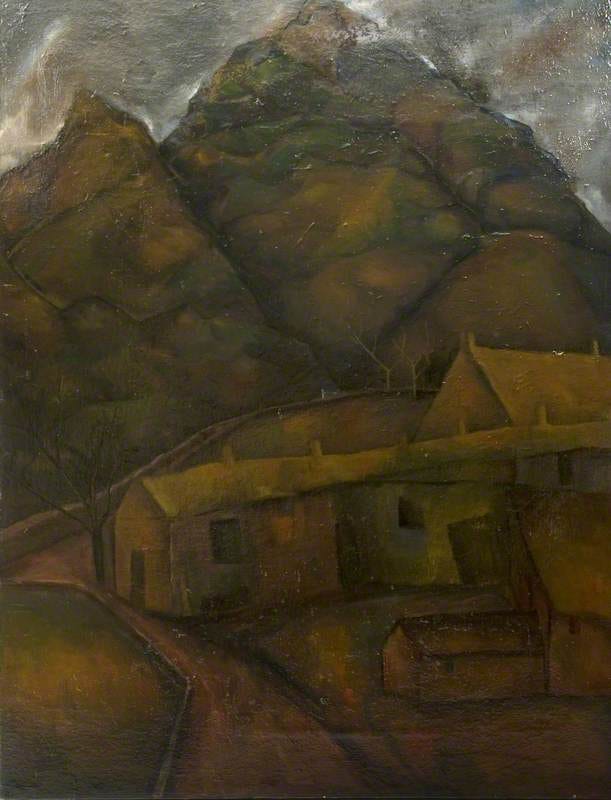

Many of Fell’s earliest paintings were of the high Cumbrian fells. However, like many of her post-war contemporaries, Fell did not paint the Neo-Romantic landscapes of her predecessors. Instead, she painted a more realistic, dark, and austere view of her world, far removed from the chocolate box views of the Lake District favoured by so many artists. Fell liked to use a vertical composition and tended to use a palette of dark earthy tones. The failing light of dusk and shards of bright light on the skyline were regular elements within her work. She also painted buildings in a simple, geometric style, which revealed her love of Paul Cézanne.

A major turning point in her career came when her friend David Sylvester, an eminent art critic, introduced her to Helen Lessore, gallerist of the renowned Beaux Arts Gallery in Mayfair. Lessore had a reputation for only giving shows to the best young figurative artists, and her judgment was impressive. Many of the artists to whom she gave solo exhibitions went on to have illustrious careers—Francis Bacon, Elizabeth Frink, and Frank Auerbach, to name but a few. Lessore agreed to give Fell an exhibition and also advanced her the money to buy paint and canvases. The exhibition opened in December 1955, when she was just 24 years old (making her the youngest artist to hold a solo exhibition at the gallery), and every single piece of her work sold. The success of this exhibition cemented Fell’s career and made her one of just a handful of successful working British female artists at the time.

Her first Beaux Arts Gallery exhibition also marked the beginning of her long-term friendship with LS Lowry, who bought two of Fell’s paintings and a drawing. Lowry regularly visited Fell and her parents in Cumberland and often took her on sketching trips. As well as being a close friend, Lowry was a mentor, and it was he who encouraged her to accept the offer of becoming an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1969 (associate status was abolished in 1991). She became a fully fledged Royal Academecian in 1974, a massive achievement for a woman then. The pair remained firm friends until Lowry died in 1976, just eight days after her father.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Fell turned her attention away from the summits of the Lake District, choosing instead to paint scenes from closer to her childhood home in Aspatria.5 This area of what was then Cumberland was relatively untouched by tourism, and it was a working landscape—a place where people worked hard in unglamorous jobs to feed their families. She painted snowy landscapes, farmsteads, harvesting and planting, and the Solway Coast. All themes that she remained transfixed by for the rest of her life.

I especially loved the snow scenes in the exhibition, with my favourite being Heavy Snow, Cumbria II. Fell was transfixed by the ability of snow to transform a landscape, and she painted many snowscapes throughout her career. As with her other landscapes, they tend towards bleakness. There are no yellows and pinks to represent sunlit snow, such as those that appear in snowscapes by Claude Monet. Fellss snowscapes veer more towards those of Pieter Bruegel and Edvard Munch, they are monochromatic with hints of sepia and tend to depict the harsh realities of midwinter in northern climes.

Heavy Snow, Cumbria II is one of her most reproduced images. At the exhibition, there was no indication of the location of this painting, but I think that it may be Yew Tree Farm in Coniston (I pass this beautiful farm regularly, and to me, it was instantly recognisable from the painting). You can see that the composition of the fells looks incorrect, but it is entirely possible that the fell in the background was covered in mist and so invisible in the snowy sky. However, the composition of the buildings and the stone walls in the painting is identical to that of Yew Tree Farm in the picture below, and whilst the tree in the front field is no longer there, it was present in older photographs of the farm. Maybe she visited the South Lakes on one of her trips with Lowry?

Sheila Fell died unexpectedly on the 15th of December 1979, she was just 48 years old. Tragically, in an interview for the Sunday Times, which took place the day before her death, Fell told the writer and broadcaster Hunter Davies that she fully intended to live until she was 104, as that would give her the time she needed to paint all of the paintings in her head.

About the author: “I’m inspired by nature. I enjoy creating images of places that I would like to live—lots of remote northern landscapes, with sheep dotted around.

I work with cyanotype printing and collage. I also produce digital paintings of my work. I mainly enjoy putting all of the above together and creating mixed-media work. I have also been experimenting with linocut for the last 9 months, and a selection of my linocut work will be available shortly.

I am heavily influenced by folk art, the seasons, the sky, and illustration. Most of my work centres around isolated places (basically, landscapes that I would love to live in). These landscapes are typically inspired by where I live (Cumbria), northern England and Scotland. Over the last few years, I have become increasingly inspired by Scandinavian art and the Nordic landscape, especially that of Sweden.”- Lindsay Steel

Sheila Fell: Cumberland on Canvas ran at Tullie until the 16th March 2025. It then moved to Sunderland Museum and Winter Garden where it ran from the 10th April until the 28th June 2025.

See more of Lindsay’s work on her substack, her website lindsaysteelart.com and on Instagram.

1. The historic county of Cumberland is now part of the county of Cumbria. However, a reorganisation of local government in Cumbria in 2023 led to the recreation of Cumberland as a unitary authority, which includes most of the historic county. The area includes the city of Carlisle, the northern flanks of the Lake District (including England’s highest mountain, Scafell), parts of the North Pennines, and the Solway Coast.

2. In Cumbria, the word fell describes a hill or mountain with steep slopes, rocky terrain, and barren summits. It comes from the Old Norse word fjallr, which describes a large and flat mountain. The Norse are thought to have arrived in what is modern-day Cumbria around 925 AD.

3. Headstocks are the workings of a coal mine that you can see from the surface— the tall, often steel, framework structure above a mine shaft, which is used for hoisting machinery, people, and materials up and down the mineshaft.

4. When Sheila Fell was studying at Carlisle School of Art, it was situated in Tullie House.

5. One exception to this was Skiddaw, the mountain that could be glimpsed from her childhood home.

Categories: art, featured, featured artist

Great work, interesting artist. thanks!

LikeLike

LikeLike