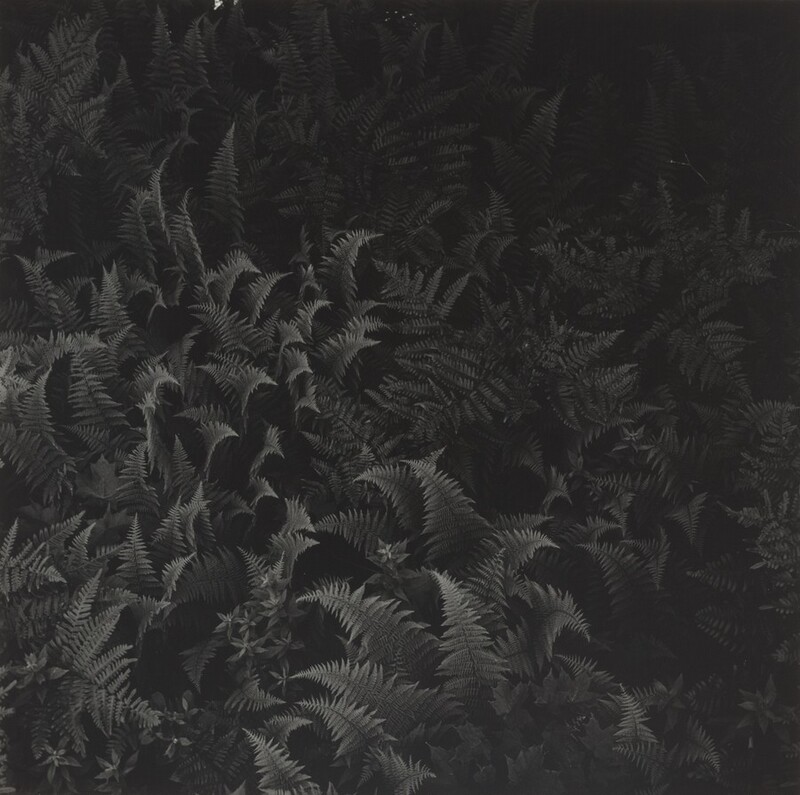

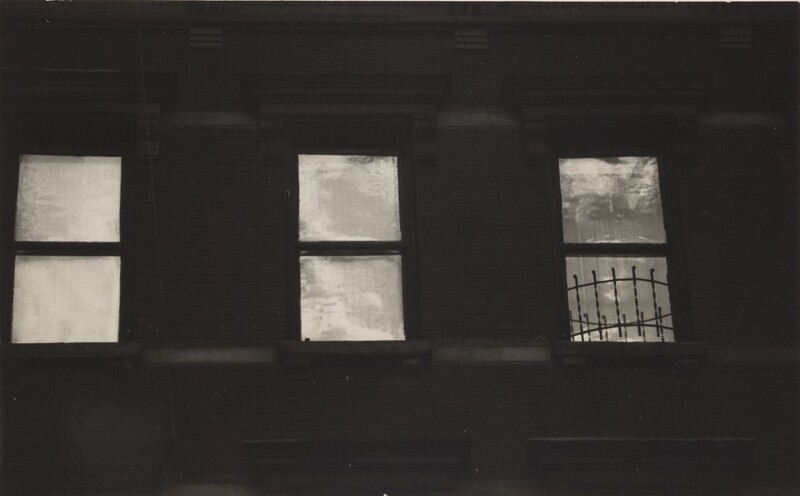

With a few stories spanning a few decades, photographer Neal Rantoul shares his affection and admiration for fellow photographer, teacher, and friend Harry Callahan. Neal Rantoul, a photographer and educator based in New England, is one of the most influential American photographers working today. His work, often landscapes seen from aloft, has a profoundly quiet yet eloquent voice, with a graceful poetry of light and space. Harry Callahan hailed from Detroit and worked in a Chrysler plant. He joined the company’s camera club, taught himself photography, and went on to become one of the most important of American photographers. His work, full of darkness and light, depth and gentle humor, is of walks around his city, of his wife and daughter, and of grass, shoots, ferns, and trees.

By Neal Rantoul

Those of you that know me know I studied at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design) with Harry Callahan. I also spent my two graduate years studying with Aaron Siskind as well. I transferred into RISD as a junior, finished with a BFA in Photography in 1971 and then continued on in graduate work graduating in Photography in 1973 with an MFA. My longest-running friendship from those days has been with Henry Horenstein, who also came to RISD as a junior and stayed through graduate studies. Henry teaches at RISD and is a fantastic photographer and author of many many books.

Harry Callahan was a complex and wonderful person, difficult to fathom for someone as young as I was but a strong influence for a student so excited by making pictures and a powerful example and mentor. There are many stories and remembrances about Harry, both during the time I was a student and after as well.

The first story about Harry is when I was about six years out of school. He and his wife Eleanor still lived in Providence in 1979 and occasionally I would go down from Cambridge, MA where I lived to see them. In the summer of 1979 I had traveled to Europe, not for the first time, but for the first time to make pictures. I started in Germany, drove through Paris to southern France, flew to London, drove up through England to the highlands of Scotland north and west of Edinburgh. I was working in black and white, shooting with a single lens Rollei SL66 with Kodak’s Plus- X film and in infrared using a 35mm Leica M3. I had a wonderful time, no big surprise. I shot a lot and came back to begin processing the film. That fall I was teaching both at New England School of Photography in Boston and Harvard University so was pretty busy but when I had time I would go into the darkroom in my apartment, develop some film and begin making 11 x 14 work prints of some of the things I’d shot in the summer.

I remember I couldn’t make much sense out of what I’d shot. There didn’t seem to be any logic or cohesion to what I’d done that I could see. But I carried on and by Christmas break I had now amassed several boxes of prints all with the same problem: no substance. Now I was concerned. What did I do? I called Harry and asked him if he’d mind me coming to Providence to see him and could I show him some work? He said, sure, come on down.

When I met with him at his house along Benefit Street we covered some pleasantries and did a little catching up and then I told him what my problem was. He looked through the box of prints that I had brought. I told him I couldn’t make any sense of what I had. He seemed to understand this right away and then told me he’d had the same thing happen to him. In 1957 Harry had traveled to France for several months with Eleanor to photograph. When returning he had the same problem. Too overwhelmed by the new, too out of sorts compared to where he’d come from, the place too foreign to assimilate, not there long enough to get in it and understand what he could do with it. I certainly didn’t have a clue I was making such a scattered group of pictures in Europe in 1979. I thought I was just continuing to photograph as I knew how to. Wrong. I went home that day severely humbled as I knew Harry was right. I hadn’t made anything worthwhile except to succeed at making pictures of things I hadn’t seen before through first impression. Substance? No. Was I saying anything in the pictures, telling a story? No. Thank goodness I learned this lesson early in my career. I never did anything with all that work, never final printed them, never made portfolios, or took them around to museums and galleries to get them shown. Hard pill to swallow but a very good lesson. I see this very often today in other’s work when I review portfolios: making pictures from trips is very dangerous.

So thank you, Harry. He had a way of setting you straight in a very understated and non-condemning way.

Are all the series that I’ve made since from travels wonderful? No. It has been a career-long struggle to make pictures that count from new places I visit. To make pictures that raise the bar on the genré, that contain some continuity, cohesion, thought and emotion, that say something. The point is, as my friend Patrick Philips says (he publishes the magazine “Martha’s Vineyard Arts and Ideas”: MV Arts & Ideas) to make pictures that “tell a story”.

Harry said: “Photography is an adventure just as life is an adventure. If man wishes to express himself photographically, he must understand, surely to a certain extent, his relationship to life.”

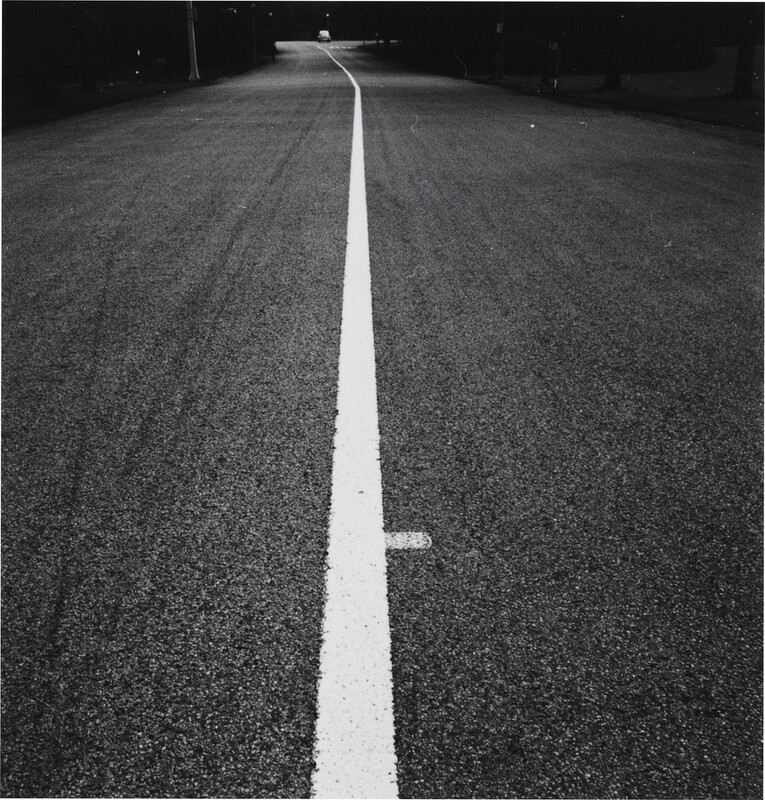

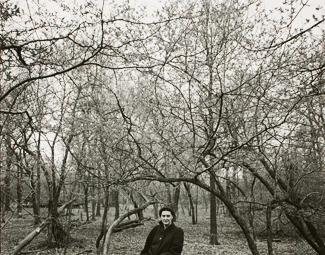

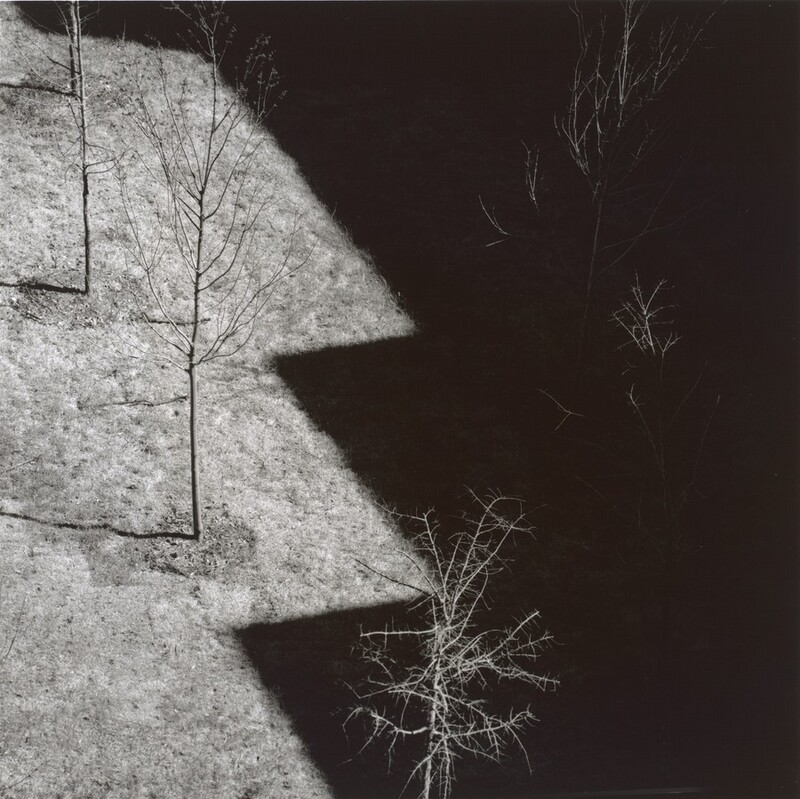

The work of Harry Callahan:

I am struck these days, as I age, how little history people know or care about.

In my own field of photography as an art this is often born out by how important someone’s work was while they were alive and how insignificant it seems now that they are gone.

Isn’t history how we learn from past mistakes? Isn’t history to see what precedents there have been?

This is another story about Harry.

Harry was invited to Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1995 by Carl Mastandrea of the Boston Photo Collaborative to give a presentation on his work. I was on the island for part of that summer and had a show of island landscapes at the MV Museum up at the same time. The day for his talk arrived and as the afternoon faded into evening the sky was darkening, a storm approaching. It was hot and humid, the air lifeless. As the crowd arrived at the Chilmark Community Center where Harry was to talk, the sky had turned very black and we could hear thunder in the distance.

The windows were open, the wind blowing things around, the audience was getting concerned and edgy while Harry continued. All of sudden lightning stuck the building, the power went out — Bam! — and Harry was standing there in the dark hall, the lightning having arced up the microphone cable and right to where Harry was standing.

Harry began his talk, standing up front at a lectern, speaking into a microphone. The house was packed with the overflow standing in back, kids cross-legged on the floor in front, Harry talking about his work in the darkened room, slides thrown up on a big screen. Crack! Came the thunder, the wind picking up as the storm approached. Harry continued, now his voice was competing with branches thrashing outside. The windows were open, the wind blowing things around, the audience was getting concerned and edgy while Harry continued. All of sudden lightning stuck the building, the power went out — Bam! — and Harry was standing there in the dark hall, the lightning having arced up the microphone cable and right to where Harry was standing. For an instant the crowd was in shock, immobile in surprise. Was Harry hit by lightining? Was he all right? For several minutes the power was out, the battery-powered emergency lights were on and people were fussing over Harry to see if he was okay, the room bathed in a dim glow. Harry was standing there seemingly all right but very quiet, appearing to be wrestling with what just happened. A few minutes later the power went back on but, as the microphone was toast, people were asked to come forward to be able to hear Harry speak. The whole dynamic of the presentation changed then, Harry loosened up and the crowd was now experiencing something warmer and more intimate, as though in a conversation between friends rather than in a formal lecture.

Harry and Eleanor flew to New York the following day to visit with Eleanor’s sister. Harry had a massive stroke a few days later in NY that knocked him back and that he never fully recovered from.

Harry was in his eighties that summer and we never did know if he’d been struck by lightning or not. I always felt there was a connection between the lightning storm that night in Martha’s Vineyard and Harry’s stroke, but I never knew for sure.

Harry was a very big deal in 1995, his work shown and collected universally all over the world. He had been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom earlier and was the US representative to the Venice Biennali as well. He had major shows at the National Gallery in DC, MOMA in New York and on and on.

Time holds still for no one and Harry’s work is now seen in the light of present times. Few seem to go back to look, to learn from him. It’s a shame.

In my first story about the photographer Harry Callahan I referenced something that happened earlier in my career. This story happened much later, close to the end of his life.

Eleanor and Harry moved to Atlanta after his time at RISD to be closer to their daughter Barbara and their grandchildren. During the nineties, I took trips to Atlanta three times. Once for an SPE (Society for Photographic Education) conference, again on my own and a third time to attend a conference of university deans and presidents.

He told me that he would walk across the street to photograph in the park and that he was photographing the trees there. We went down the hallway to where he had a darkroom. He pulled out some 8 x 10 black white prints he’d made of the bare branches of the trees across the way. The branches were very black with white sky behind them and it was clear he was pointing his camera up.

At the last one I called the Callahans to see if I could visit. I took a cab over on a day in late February that was as cold as anything I can remember in Boston. Harry had had a stroke the year before and was slowed down considerably. When I arrived I found the same Harry, but different too as his speaking was clearly faltering and he moved very slowly. They both were pleased to have a visitor. After catching up Harry said that he had some new work he wanted to show me. This came as a surprise as I hadn’t thought he’d been able to work. He told me that he would walk across the street to photograph in the park and that he was photographing the trees there. We went down the hallway to where he had a darkroom. He pulled out some 8 x 10 black white prints he’d made of the bare branches of the trees across the way. The branches were very black with white sky behind them and it was clear he was pointing his camera up.

Harry Callahan turned to me and said, “I like trees, Neal”.

Now you wouldn’t think this would be a momentous thing to say to someone but put in the right context you can see why it practically knocked me off my feet. Here was Harry Callahan, one of the masters of the twentieth century in photography, telling me that he liked trees at the very end of a career that had practically started with photographing trees. Reference pretty much anything in Harry’s work over his whole career and trees will loom large.

That was my last visit with Harry as he died about a year later. He was a powerful force to us as students and I still miss him to this day, as I know many many others do as well.

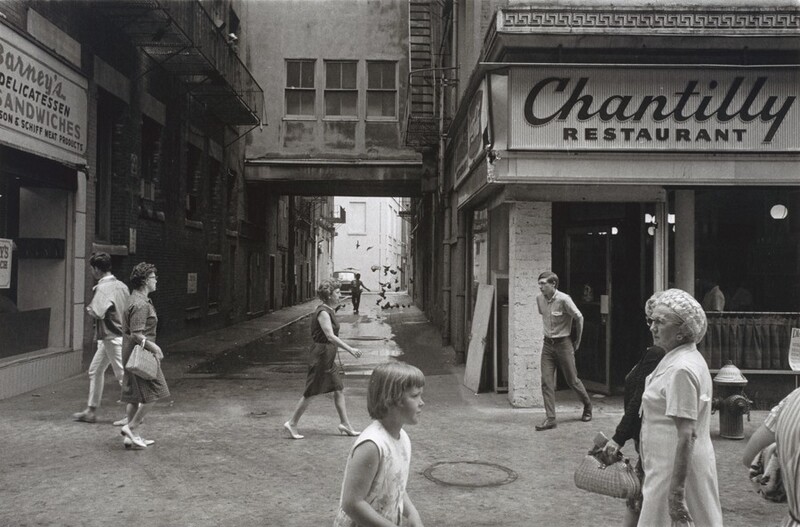

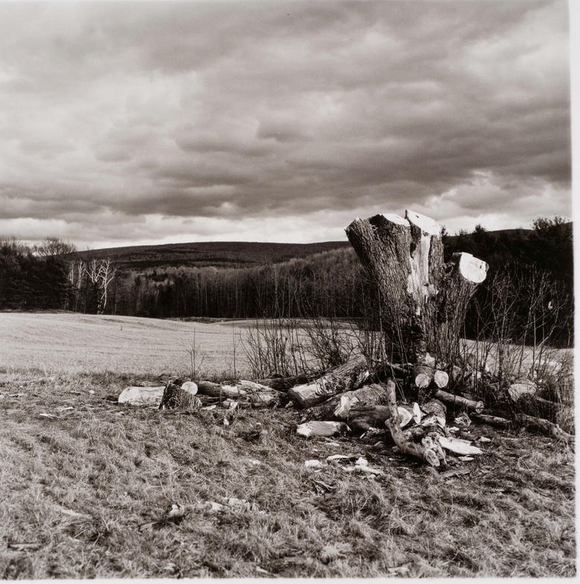

The work of Neal Rantoul

Neal Rantoul is a career artist and educator. He retired from 30 years as head of the Photo Program at Northeastern University in Boston in 2012. He taught at Harvard University for thirteen years as well. He now devotes his efforts full time to making new work and bringing earlier work to a national and international audience. See more of his work at nealrantoul.com.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, memoir, Photo Essay, photography