By Chimezie Chika

The stereotypical image of a coconut palm in the background of an orange-yellow sunset greets any viewer that sees “Sunset Island”, a piece by the Nigerian digital artist, Afolabi Oluwunmi Fakunmoju, featured at a month-long exhibition in Berlin’s Nicoleta Gallery. The paradisiacal proportions of the piece, in its digital precision of sharp colour separations (blue, yellow, black, silver-white, orange, black, blue), is clear: coconut palms, a sunset, a slice of sea, a sliver of beach land, two birds in blissful flight. What is created here, with the help of conventional imagination, is an affirmation of thousands, if not millions, of idyllic images geared toward a specific audience in the world tourism industry, of which Africa plays no small part.

These kinds of images need to be seen from the right perspective, especially for the stories they amplify and entrench. Essays such as Deborah Bright’s “Marlboro Man” do a great job of discoursing at length the insidious reaches of archetypal signifiers in images we often take for granted. The results of these archetypal works is that they are centralized as the true representation of people, places, and periods, which they are not.

Fakunmoju’s “Sunset Island” reveals something notable in the trend of commercial digital art in the twenty-first century: imagination, in those incestuous spheres, are an act of collective reproduction of the similar images in perpetuity. The art archives of stock photo sites are littered with thousands of photos of this nature. It is a bona fide archetype of a type of idealistic vision of Africa, the same as the even more popular images of camels (sometimes nomads) in a red sunset. These images of Africa come from the age of colonisation and exploration, the envisioning of the continent as a large landmass full of deserts, scant nomadic tribes, and expansive, green wildlife plains. Barely any humans feature in these images, which explains its very motives—to make out of it a sort of primordial curio of the world’s original state. (This is how so and so tribes live; these people don’t know what a phone looks, these are the original bushmen, I just met the shortest people in the world—the whole enterprise of touristic sensationalism propels a whole niche of travel videos on YouTube and other social media). They seem to say: come and see the world at its most ancient and untouched in Africa; there is a sort of self-gratifying, I-am-more-civilized hypocrisy to it all. If humans do feature at all in these images and videos, then the statements are mere clickbaits implied to arouse immediate curiosity: come and see humans at their most savage and pristinely uncivilized.

They seem to say: come and see the world at its most ancient and untouched in Africa; there is a sort of self-gratifying, I-am-more-civilized hypocrisy to it all

It’s all geared towards anthropological tourism in Africa—an undertaking that began more than three centuries ago. It is instructive that none of those early European fascination with a stock vision of Africa has changed. Many in the West still stubbornly insist on seeing the continent from only this perspective. This phenomenon has been reported in the inherent prejudice in the cover images of novels about Africa. More than that, modern commercial African tourism PRs, mostly run by international organizations, still insist on perpetuating images that vastly depart from the reality of the continent in the 21st century. In the eyes of these media promotionals, Africa is always a yellow beach filled with coconut palms or a paradise of wildlife (or, in a drastic twist of another extreme, a vast, suppurating slum). In other words, here is a continent good for only nice getaways or extremely well-publicised charities, which may or may not have other motives. What can be done about this bastardization of the imaginative regions of originality and creativity?

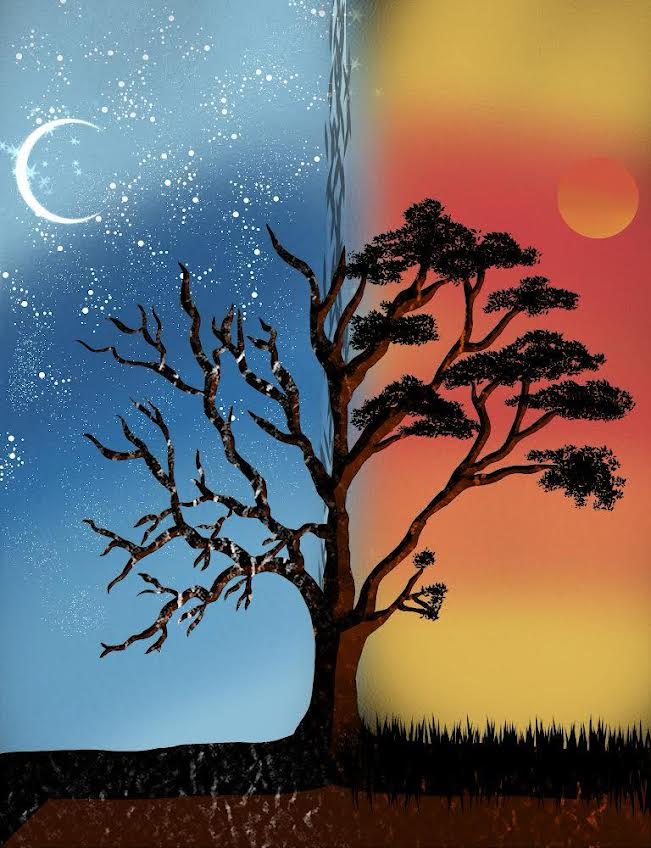

Fakunmoju’s second piece, “A Tree of Seasons”, fares better as far as digital art goes. It is given some artistic force through its clean symbolism. Here, Fakunmoju bestows simple interpretative imagery on the painting. The ironic result is a large, multi-branched, acacia-like tree with a dual appearance clearly outlined by the different features in its left and right sides. On the right-hand side, the tree’s branches are blossoming and full, with dense leaf clusters and a sturdy-looking trunk. The atmosphere appears to be hot and sunny, judging from the yellow and orange dashes of the sky. The ground at the foot of the tree is grassy and soft brown. The left-hand side prefigures the exact opposite: the tree is frozen and leafless in a bluish winter environment, with a crescent moon and stars indicating nighttime. White traces of snow on the tree’s naked branches are testaments to its lack of nourishment. The ground below the tree is bare and devoid of any traces of plant life; instead, the traces of white in the black and brown of the earth shows it is frozen.

The imagery is a primarily simple one that does not imply or hint at anything truly sublime beyond the plainness of the lines; the artist has merely painted his interpretation of the archetypal image of the tree of life. The message is therefore rather simple for this precise reason: summer and the sun nourish and blossom life, bring happiness, fulfillment, etc, while winter kills and maims life, brings unhappiness, darkness, and squashes dreams, etc. One need not begin to counsel the artist on the need to expand the reaches of his art, certainly not this writer, for if his efforts were geared towards such established archetypes, it makes great sense to also acknowledge that the ordinary public finds merits in such art, which is why one is wont to find them, for instance, in the houses of Africa’s newly gentrified, whose new-fangled prosperity expends time making desperate overtures to appear sophisticated.

“Instinct and Nature”, the best of Fakunmoju’s three paintings under review here, notwithstanding its rather bland title, converts simplicity into something really decent and unpretentious. In a good way, it appears to glean some of its gentle brushstrokes from the likes of Han dynasty nature paintings, though what we see here is much more impressionistic than those blurry oriental classics. The melding of colours—sky blue, violet, and yellow—in the sky here transcends digital obviousness and becomes almost as artisanal as an oil painting. The picture created is that of a footbridge across a creek or a small section of a river. The surroundings reveal the kind of nature that appears in freshwater bodies: reeds, lilies, and the shadow of the setting sun on the water. What could the artist be implying with such a title? Is there nature here?—yes, indeed. Instinct? I am not so sure, especially as the question that comes to mind in lieu of an answer would be: in what sense? In what sense is instinct visible here? What is visible for all to see, however, in Fakunmoju’s work, is that the artist seems not just attracted to idyllic landscapes but, for the most part, approaches the depiction of them from archetypal perspectives.

Chimezie Chika is an essayist, critic, and writer of fiction. His work has been featured in journals ranging from The Republic to Channel Magazine and Afrocritik. Find him on X @chimeziechika1

supreme! Live Updates: The Latest on [Developing Situation in a Specific Region] 2025 impressive

LikeLike