by Matthew Holtmeier

This is an excerpt, to read the full article, including the examination of Watermelon Man, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song go to Jump Cut, where this article first appeared.

Entertainment-wise, a motherfucker: critical race politics and the transnational movement of Melvin van Peebles

This article argues that the transnational movement of Melvin van Peebles is crucial in ending the dearth in African American feature film production in the United States after Oscar Micheaux’s The Betrayal (1948). By establishing himself as a global auteur, van Peebles uniquely navigates the film industry with his first three films and develops a critical race politics that questions the role of American exceptionalism in Hollywood. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) is a focal point for considering van Peebles’ political aesthetics, but I argue that in addition, this third feature-length film is the culmination of a larger project that focuses on the director’s playing industry aesthetics and practices in a minor key. In doing so, van Peebles responds to the civil rights movement in a manner now eschewed in contemporary remembering, which privileges American exceptionalism. Within this framework, I read his films as a direct challenge to this historical dismantling of radical political projects concerning disenfranchised populations in the United States, projects that include an indictment of U.S. empire. Such a case study is particularly important today with recent films from Hidden Figures (2016) to Moonlight (2016) returning to a similar divergence in the politics of films depicting U.S. race relations.

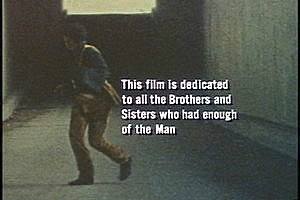

Writing about his inspiration for Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Melvin van Peebles explains that the film had to be “entertainment-wise, a motherfucker” to satisfy market conditions and deliver a political message about race in the United States.

Writing about his inspiration for Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Melvin van Peebles explains that the film had to be “entertainment-wise, a motherfucker” to satisfy market conditions and deliver a political message about race in the United States.[1] Though his goal in making Sweet Sweetback’s was explicitly political, van Peebles understood that in order to navigate the audience/industry desires that drive cinema-going and exhibition, such a politics would have to take hybrid form. He reasons, “The film simply couldn’t be a didactic discourse … The Man has an Achilles pocket and he might go along with you if at least there is some bread in it for him. But he ain’t about to go carrying no messages for you, especially a relevant one, for free.”[2]

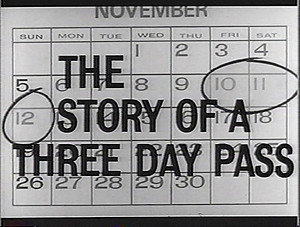

While van Peebles is perhaps best remembered for the audacity of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, he develops his strategies for navigating industry and exhibition currents in his earlier two films, Story of a Three-Day Pass (1968) and Watermelon Man (1970). In these, he strategically deals with both the French film industry and Hollywood, catering to the industrial demands of each project in order to inject them with a critical race politics that make them speak anew.

In other words, “entertainment-wise, a motherfucker” underpins a political philosophy that runs throughout his work. When he argues that Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song needs to be “entertainment-wise, a motherfucker,” van Peebles articulates his political strategy of transnational hybridization that moves between commercial, auteur-driven, and radical political aesthetics in order to address racial conflict in the United States of the 60s and 70s. Rather than always being about entertainment, however, this strategy highlights the way in which van Peebles isolates the Achilles heel of any industry in order to force it to carry his message, whether that be studio-driven films, art cinema, or independent cinema. Van Peebles articulates this strategy quite independently of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s works in which they discuss ‘minor literatures’ or ‘minor cinemas,’ but the resonance is worth bearing in mind for their argument that within each dominant mode of representation, there is a suppression of entire communities, which come to the fore when that articulation is played in a minor key.[3]

Van Peebles’s crucial extension of an argument such as Deleuze and Guattari articulate is not only that his films give voice to the under- or misrepresented, but that his work provides an alternative understanding of history.

In their original articulation in Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature (1975), Deleuze and Guattari compare minor literatures to “what blacks in America today are able to do with the English language,” referencing African American Vernacular English.[4] Van Peebles extends this kind of thinking into the realm of filmmaking. For example, Courtney Bates argues that van Peebles integrates “distinctly African American semiotic codes in order to subvert the mainstream origins of its story structure” in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.[5] I raise this reading of Peebles’ work as a form of minor cinema to draw upon the articulation of the political potential of such works. In particular, Deleuze and Guattari argue that minor literatures/cinemas “express another possible community,” and “forge the means for another consciousness and another sensibility.”[6] For van Peebles, this other sensibility shapes his political aesthetics of consciousness-raising, and he is sensitive to the U.S. colonial legacy in a way that is particularly poignant in the context of his times, especially the events surrounding 1968 and global efforts then towards decolonization. Van Peebles’s crucial extension of an argument such as Deleuze and Guattari articulate is not only that his films give voice to the under- or misrepresented, but that his work provides an alternative understanding of history. And in this case, racial history was being obfuscated in the United States in order to promote American exceptionalism. Van Peebles’ work illustrates this process so remarkably especially because within his first three feature-length films he moves through three distinct industries and excavates those voices/histories in each.

In this trajectory, van Peebles maneuvers a number of cinematic forms: second cinema, first cinema, and third cinema following his trilogy historically. I borrow this global heuristic of cinematic forms from Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino not only because their categorizations map onto van Peebles’s trilogy, but also because he moves transnationally himself. Transnational movement is key to understanding van Peebles’s politics because he positions his own racial critique of the United States in relation to global movements against colonialism and Empire. This becomes his way of providing a critical perspective on the 1960s U.S. civil rights movement. As Cynthia Young argues in Soul Power, such a perspective is needed: “Characterized by racial myopia and North American exceptionalism, [a] New Left-centric historiography has diminished the influence of domestic movements for racial and economy equality and international liberation struggles.”[7]

Furthermore, in the 1960s and now, film industries also contribute to this notion of North American exceptionalism, through films like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). Van Peebles counters this by denying the suggestion of an emancipatory teleology moving towards a freer society by acknowledging the colonial underpinnings of the United States itself and their continued operation through cinematic institutions at the levels of genre, industry, and representation. Van Peebles’s skepticism, contemporaneous with civil rights, finds validation for us today in the continued critical race politics of Black Lives Matter.

In our own time, “entertainment-wise, a motherfucker” becomes the expression of a carefully articulated political strategy that presages a response to Mahnola Dargis and A.O. Scott’s article, “Watching While White: How Movies Tackled Race in 2016.” Scott notes a trend in films such as Fences (2016), Hidden Figures (2016), and Loving (2016) as they return to the 50s and 60s, “amid all the injustices and unresolved contradictions, civic progress, a sense of national purpose, and expansiveness” … “without abandoning Hollywood feel-good conventions.”[8] As racial tension is on the rise in the United States, the response these recent films from 2016 give to that tension resembles the studio response of the 1960s to the civil rights movement with films like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. It’s a film that is not critical of racial tension as much as affirmative of certain liberal fallacies that mitigate real structural critique. This kind of cinematic narrative contributes, as Aziz Rana argues, to a “vision of the country as intrinsically—if incompletely—liberal [that] systematically deemphasizes those forms of economic and political subordination that continue to mark the experience of historically marginalized communities.”[9]

“… the appellation Third World served as a shorthand for leftists of color in the United States, signifying their opposition to a particular economic and racial world order.”

The above films’ affective responses to civil rights issues disentangle contemporary structural inequality from the histories of colonialism and Empire. This contemporary repeat of the 60s has a film aesthetics that emphasizes a liberal teleology and affirmation of U.S. creedal politics,[10] especially in relation to Black Lives Matter, a movement that acknowledges that such a liberal teleology is a fallacy. Such a retrograde nostalgia about struggle in contemporary cinema emphasizes for me the importance of van Peebles’s transnational movements and connection to larger political aesthetics actively engaged with Empire. As Young notes, “the appellation Third World served as a shorthand for leftists of color in the United States, signifying their opposition to a particular economic and racial world order.”[11]

Situating van Peebles’s work in relation to this political framework of U.S. colonial history illustrates the importance of his work both at home and abroad, as well as the massive positive response to a film like Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song among political groups like the Black Panthers. Young’s argument that these politics have been historically deemphasized also helps to explain van Peebles’s relatively quick decline in popularity and why Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song has quickly faded from U.S. consciousness, whereas Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner remains.

In fact, in 2017 Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was inducted into the U.S. Library of Congress film registry, a seeming facile response to Black Lives Matters. This same year, I responded to the Society for Cinema and Media Studies committee’s call for Library of Congress nominations by supporting the induction of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song for its relevance given the contemporary political climate. The committee responded that they would indeed pass on my recommendation, but that this film had been recommended many times before to no avail. Given the history of its failed recommendation, I don’t make this point to isolate the individual choices of the Librarian of Congress, but to illustrate the ways in which structural affirmation of American exceptionalism proceeds. I would not deny the presence of significant political films in the National Film Registry,[12] but wish to illustrate that certain films get privileged by public memory and others do not, and also to identify what political issues cross the line of violating creedal narratives. The reconciliation of race relations in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner seems appropriate, whereas the police brutality and ensuing violence of films such as Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama (1979) get left out. Analyzing this politics of selecting films for a national registry and preservation reveals several specific instances where the state has upheld American creedal narratives and marginalized radical politics. The particular instance here is part of a long, historical process.

To make an argument for understanding van Peebles’s trilogy as a critique of American creedal narratives, I will start by situating this trilogy within its political moment. There was a dearth of films made by African Americans to which van Peebles responds, and a context of Black radical politics that shapes his response. I will then explain the importance of understanding his political approach. In this regard, I have found useful Jean-Luc Comolli and Paul Narboni’s categorization of political cinemas, which identifies filmmaking approaches that alter dominant signifying regimes; such a categorization avoids capitulating to American creedal politics as industry standards. Significantly, in the case of van Peebles, his work is tied to his own global movement, which informs his political response to Empire — a key facet of political positions in the 1960s critical of American creedal politics. Finally, I will illustrate the ways in which each film approaches questions of Empire. Understanding van Peebles original trilogy as critical of Empire excavates its political importance for today, almost a half-century later, where many relatively popular ‘political’ films still observe conservative strategies that obfuscate the United States’ colonial underpinnings.

Lily-white unions and third world folks: the contradictions of American exceptionalism and Empire

In his self-written account of the making of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, van Peebles recounts his desire to go into filmmaking, “The biggest obstacle to the Black revolution in America is our conditioned susceptibility to the white man’s program … and it is with this starting point in mind and the intention to reverse the process that I went into cinema in the first fucking place.”[13]

The more he became acquainted with the film industry, however, the more he realized that correcting racial representation was perhaps secondary to creating opportunities for African Americans to work in the U.S. film industry in fundamental roles. A key site of this challenge was working with unions within the “lily-White fortress,” as he would later describe the film industry of the late ’60s.[14] With the Columbia picture Watermelon Man under his belt, van Peebles decided that with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, “I wanted 50% of my shooting crew to be third world people.”[15] The dialectic he establishes here between the white majority industry and crews including people of color is important for two key reasons. First, rather than focus on racial representation, which the industry already began acknowledging in its own problematic way during this time,[16] he approaches race in terms of structural inequality and exclusion. Such an approach aligns with Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation with its focus on systemic thinking, and Aziz Rana’s conception of a “settler empire.”[17] Second, he explicitly uses the term ‘third world’ to refer to people of color, which implicates the U.S. role in global Empire, and aligns him with the political movements that have a transnational consciousness.[18] In each case, van Peebles worked against notions of American exceptionalism that were actively being articulated in the U.S. mainstream in response to civil rights movements.

The term American exceptionalism has been used to attempt to describe what makes the United States unique as a global power, from its resistance to communism to its seeming integration of diversity within its concept of the nation. For example, in The First New Nation, political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset argues that two key values, equality and achievement, mark this exceptionalism: “The value we have attributed to achievement is a corollary to our belief in equality. For people to be equal, they need a chance to become equal. Success, therefore, should be attainable by all, no matter what the accidents of birth, class, or race.”[19]

Lipset acknowledges that his account of American exceptionalism is an attempt to reconcile the presence of corruption and inequality in the United States with this ideology of achievement, but nonetheless what marks the country out as unique is that, unlike nations in Central and South America that subsequently broke away from colonial rule, the United States developed “a relatively integrated social structure.”[20] The civil rights movement thus illustrates a key moment in articulating this process towards American exceptionalism, with its ideology of equality and achievement. Such exceptionalism, however, relies on a creedal narrative of the United States being defined against other colonial Empires.

By acknowledging U.S. colonial underpinnings, black radicals such as Carmichael and Hamilton establish links between the struggles for civil rights in the United States and larger decolonial movements abroad, such as those taking place in Africa and Asia. In this context, van Peebles’ desire to hire ‘third world folks’ is not an offhand reference to race or class, but an articulation in line with those radicals. Rana explains this link between the United States and struggles abroad: “Black radicals recognized […] the struggle of nonwhite groups in the American interior was much like the struggle of nonwhite groups around the world. As Carmichael and Hamilton put it, the ‘institutional racism’ of the domestic United States ought to be known by ‘another name: colonialism’ […] Twentieth-century black radicals thus imagined revolutionary reform in terms of decolonization. Independence movements in the third world were in the midst of fighting to transfer economic and political power from imperial elites to the historically colonized, and the same kind of transfer was necessary in the US.”[21]

To return to van Peebles, this transfer of power might begin to take place through the director’s navigation of film industries, from French, to American, and eventually to independent film production. It’s a symbolic small-scale decolonization he achieves with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. The Black Panther’s endorsement of that film illustrates van Peebles’s success in integrating into this larger conversation, with Huey P. Newton writing in The Black Panther that it would be required viewing for Panthers.[22]

Between The Betrayal in 1948 and Story of a Three Day Pass in 1968, no African Americans were able to make feature films, and this latter film was made outside of the United States entirely.

This dual articulation between an American creedal narrative of equality and the linking of 1960s U.S. politics to global politics of decolonization takes place within the film industry, albeit articulated quite differently in each case. Historically, black filmmaking in the United States had long been a segregated industry, with ‘race films’ made with African American casts playing in African American theaters. This lasted until Micheaux’s The Betrayal in 1948, and was followed by a dearth in African American film production. Between The Betrayal in 1948 and Story of a Three Day Pass in 1968, no African Americans were able to make feature films, and this latter film was made outside of the United States entirely. Melvin Donalson points to two main reasons: “(1) the history of stereotypical screen images of blacks, and (2) the lack of a power base by blacks in the business of filmmaking.”[23]

In the ’60s as the Hollywood industry takes up the political sentiments of civil rights in its drive for greater African American representation, however, its response to these two issues reinforces American exceptionalism, rather than incorporate the more radical approach of Carmichael and Hamilton. Sidney Poitier’s films during this period provide excellent examples of such integrative representation, as in films such as The Defiant Ones (1958), Lilies of the Field (1963), or In the Heat of the Night (1967). But principally it’s a studio film and a white director, the immensely popular Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, distributed by Columbia and directed by Stanley Kramer, that serves as a key case study for its affective positioning of race relations.

Mrs. Drayton first upon first seeing Dr. John Prentice, as her daughter muses upon her future name, “Joanna Prentice I’ll be.”

Later lambasted by van Peebles in Watermelon Man, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner responds directly to Lipset’s ideology of equality and achievement; it does so through dramatically questioning and then affirming liberal values. The film depicts the single day in which the wealthy San Franciscan Joanna Drayton (Katharine Houghton) returns from a trip to Hawaii with the world-renowned Dr. John Prentice (Sidney Poitier) to tell her parents that they are going to get married. The central drama revolves around the Draytons’ acceptance that their daughter might marry a black man (and so suddenly: they met 10 days prior and the film establishes a deadline structure by requiring the Draytons to accept or reject the situation that day). The Draytons are conflicted, because they raised their daughter according to America’s creedal narrative of equality. As Joanna describes her father: “My dad is a lifelong fighting liberal who loathes race prejudice and has spent his whole life fighting against discrimination.”

Nonetheless, when confronted with a situation that asks him to enact these ideals, beyond referring to their black maid Tillie (Isabel Sanford) as “family,” Mr. Drayton’s (Spencer Tracy) indecision spans the entirety of the film. The film ends with an emotional monologue wherein he understands their love by remembering the genesis of his relationship with Mrs. Drayton (Katharine Hepburn), decreeing: “And if it’s half of what we felt … that’s everything.”

The remainder of the monologue is spent decrying the racist responses they will no doubt receive, and arguing that ultimately they must prevail. Such a speech is a clear analogy for the civil rights movement and an appeal to the creedal narrative.

Unceremoniously, the scene ends with Mr. Drayton bantering, “Well, Tillie, when the hell are we going to get some dinner?”

The film cuts between all of the characters during the delivery of this final monologue, as the rapt soon-to-be family looks on, with tears in the eyes of Mrs. Drayton and Mrs. Prentice (Beah Richards) — no doubt the intended response of the audience as well. The thick pathos of the scene depends upon and accentuates an American exceptionalism that is affirmed in these moments: only in the United States could such a progressive stance be taken, and audiences are, presumably, emotionally moved by their own affirmation of core American values in the scene. Unceremoniously, the scene ends with Mr. Drayton bantering, “Well, Tillie, when the hell are we going to get some dinner?”

This line’s incongruity only serves to reinforce the emotional refrain that has just taken place, and they are ushered into the dining room with Jacqueline Fontaine’s rendition of “The Glory of Love.” The emotional end is no surprise in cinema’s melodramatic navigation of domestic conflict standing in for larger societal issues, but its affirmation of Mr. Drayton’s speech serves to obfuscate the critical race politics articulated by more radical civil rights leaders. In addition, the film illustrates the two reasons Donalson gives for a dearth in African American filmmaking: stereotypical representation and lack of a power base. Poitier’s character is undoubtedly a ‘good stereotype,’ but is nonetheless a stereotype. As van Peebles put it, “Sidney was a wonderful actor, and we were proud, but nobody could really relate because the characters he was given to play were surreal, more from heaven than the ‘hood.”[24]

For van Peebles, the integration of Poitier’s characters into the film industry served only as postwar “flag-waving to unite the nation,” which illustrates van Peebles’ acknowledgment of the industry’s posturing in relation to American exceptionalism.[25]

*******

In doing so, they opt for a transnational politics of emancipation, rather than integration without equality.

I turn now to analyze Story of a Three Day Pass, Watermelon Man, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song to provide examples of a different response than the 60s studio films from white directors. Van Peebles’ films operate according to a critical race politics that acknowledge but refute industry operation along the lines of the creedal narrative outlined here. In doing so, they opt for a transnational politics of emancipation, rather than integration without equality. Through navigating the ’60s and early ’70s political economy and exploiting dominant aesthetic and industrial practices, van Peebles deftly maneuvers cinematic models of international art cinema, commercial cinema, and independent cinema respectively. I argue that he does not prefer one of these modes over the other, but that he finds ways in which to exploit each in order to find the ways in which an African American voice can build upon the representational opportunities offered by each. [20] Rather than the heavenly surrealism of Poitier, he presents a diverse set of images that contribute to the larger conversation surrounding and critiquing American Empire.

Second, first, third: aesthetics out of joint and the transnational navigation of cinematic industries

The most significant aspect of van Peebles’ early career is not only that he ended a 20-year gap in African American feature film production, but that he navigated three different modes of production to do so. This includes global sites of film production, France and America, but also industrial and aesthetic frameworks, first, second, and third cinema following Solanas and Getino’s manifesto for a new form of political cinema. I take up the framework from Solanas and Getino’s landmark essay, “Towards a Third Cinema,” because of van Peebles’ explicitly political motivations in entering the film industry, as well as the historical accuracy by which their framework describes the types of filmmaking that van Peebles navigates, and the fact that their thinking is contemporaneous to the moment in which van Peebles operates. His transnational movement and transition from commercial to independent production was necessary for breaking into feature film production in the 1960s, however, because he was black.

These career moves resonate with the issues Donalson raises when describing impediments to African American film production: first, van Peebles turned to filmmaking with his short films produced in 1950s San Francisco in order to correct negative stereotypes of African Americans in the U.S. film industry; second, he navigated the lack of a power base of African Americans by leaving the United States entirely. While moving abroad allowed him to uniquely maneuver the U.S. film industry, it is also significant that he approached each industry he worked in critically rather than simply working in the mode of said industry. By playing each industry in a minor key, an appropriate analogy for van Peebles who was also a musician, he actively engaged with global movements towards decolonization and implicated the United States’ colonial past in the politics of the 1960s and 1970s.

They called for a radically different type of cinema in terms of production, exhibition, and the ways in which politics were delivered cinematically, which they would call third cinema.

Solanas and Getino published their manifesto “Towards a Third Cinema” one year after making their film which would embody its principles, Hour of the Furnaces (1968). The manifesto, with a specific interest in the ways that cinematic practices from the United States influenced Argentinian film production, denounced neocolonialism for overwriting local cinematic styles and bringing with it American ideologies as well. The authors considered cinema in this regard to be no less than part of the larger neocolonial apparatus by which North America exerted control over and exploited the resources of South America. They called for a radically different type of cinema in terms of production, exhibition, and the ways in which politics were delivered cinematically, which they would call third cinema. They argued that this type of cinema “can be found in the revolutionary opening towards a cinema outside and against the System, in a cinema of liberation.”[26] They acknowledged that in Europe, art cinema was being produced in a distinctly different style from the commercial cinema of the United States, and they called this second cinema. For Solanas and Getino, second cinema had political potential but ultimately could not deliver a political message because these filmmakers “have already reached, or are about the reach, the outer limits of what the system permits.”[27] They called Hollywood first cinema, not because of a particular historical trajectory, nor because of Cold War frameworks that might position the United States as part of the ‘first world,’ but because of the position of power Hollywood occupied in a larger neocolonial hierarchy that spanned from commercial cinema that supported majoritarian economic and ideological models, to art cinema/second cinema that was individual and potentially political, and finally to a cinema of decolonization/third cinema that directly critiques structures of power.

In their manifesto, Solanas and Getino argue that the role of third cinema is consciousness-raising, also an important part of the radical black politics of the 1960s, which are reflected in van Peebles’s cinematic politics. Solanas and Getino introduce the concept of the ‘film act,’ an understanding of film-viewing as an event that includes three facets:

- “The participant comrade, the man-actor-accomplice who responded to the summons [of the film/filmmaker];

- The free space where that man expressed his concerns and ideas, became politicised, and started to free himself; and

- The film, important only as a detonator or pretext.”[28]

… rather than privileging a non-commercial space for the transformation of subjectivity, van Peebles sneaks this experience into as many markets qua modes of production as possible.

Rather than provide the commercial experience of film as entertainment, third cinema aspires to create events that cross the lines between film viewing and a political rally. The viewer, in their perspective, should leave the experience critically engaged, quite the opposite of a creedal affirmation insofar as creedal narratives affirm dominant ideologies. Broadly speaking, this suggests a relatively straightforward alignment between van Peeble’s critique of American exceptionalism and third cinema, but I do not want to over-determine this relation because there are at least two key differences: First, rather than privileging a non-commercial space for the transformation of subjectivity, van Peebles sneaks this experience into as many markets qua modes of production as possible. Second, van Peebles delves deeply into the subjectivity of his characters, an approach that Solanas and Getino align with the auteurist second cinema and critique as only “an attempt at decolonization.”[29] As Rachel Gabara argues, “Third Cinema, to the contrary [of art cinema], was interested in the People, in popular history and living conditions, and not at all in individual psychology.”[30]

In Contemporary Political Cinema, I argue that the approach of so-called ‘minor cinemas,’ which I here suggest resonate with van Peebles’s work, aligns with many of the political principles of third cinema, but it departs in its emphasis on individual stories or subjectivities.[31] Likewise, van Peebles’s approach deftly navigates a number of industrial frameworks, but even extends the principles of third cinema as well, by illustrating how the political aims of third cinema might come from within any industry, if the director acts as interlocutor by making decisive breaks with the modes and practices of said industry.

In this way, van Peebles directly responds to the ideological structures that determine practices and aesthetics that emerge from the industries he works within. Comolli and Narboni, in their famous essay “Cinema/ Ideology/ Criticism.”[32], posit a number of approaches political cinema might take in response to the ideological structures of film industries. In this essay, the authors give seven categories of political cinema, A through G, with varying levels of political content. But first, they argue, “Every film is political, inasmuch it is determined by the ideology which produces it,” though there are certain forms that are undoubtedly more political than others.[33] If we think through van Peebles’ first three feature films using Comolli and Narboni’s framework, it reveals how quickly and adeptly he navigates a number of approaches to political cinema, moving towards the more critical end of the spectrum with each film.

Story of a Three Day Pass was made within the context of and is at least similar to the French New Wave, which its jazzy, youthful style reflects, albeit with a narrative that focuses explicitly on race.

His first film, Story of a Three Day Pass, conforms to their category D: films having “explicitly political content … but which do not effectively criticize the ideological system in which they are embedded because they unquestioningly adopt its language and imagery.”[34] Story of a Three Day Pass was made within the context of and is at least similar to the French New Wave, which its jazzy, youthful style reflects, albeit with a narrative that focuses explicitly on race. Watermelon Man operates according to category E: “films which seem at first sight to belong firmly within the ideology and to be completely under its sway, but which turn out to be so only in an ambiguous manner… the films we are talking about throw up obstacles in the way of ideology, causing it to swerve and get off course.”[35]

At first sight, Watermelon Man appears to be a typical studio comedy, although van Peebles consciously throws up obstacles that begin to break down the ideological function Comolli and Narboni associate with studio films. Finally, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song achieves category B. These are “films which attack their ideological assimilation on two fronts. Firstly, by direct political action, on the level of the ‘signified’… linked with a breaking down of the traditional way of depicting reality… Economic/political and formal action have to be indissolubly wedded.”[36]

In this film, political form and content are wedded, thus it is no surprise that here van Peebles produces the most radical political message of his films, a message to which Huey P. Newton and the Panthers responded.

Before providing a political analysis of the form and content of van Peebles’s films, I will quickly situate each in its historical moment in order to provide the context of how he navigates the previously mentioned categories. I provide this historical trajectory separate from individual analysis of the films in order to clearly articulate van Peebles’ political development in relation to global geopolitics. In this respect, I answer Christina Gerhardt and Sara Saljoughi’s call in 1968 and Global Cinema to think outside a “center-periphery model” and instead to “consider the relationships among social movements globally,” and to consider “how the global interplay of the 1960s shifted film language.”[37] In the case of van Peebles, I argue that he moves between different spaces and industries, but rather than keep them distinct in his films, he modifies one with the other in order to critique whichever industry he currently works within.

In the 1960s, van Peebles was invited by Henri Langlois to show his short films at the Cinémathèque Française, and presumably it was there that he learned more about the French film industry — in particular the funds available for first time directors, and the general desire to see young directors get their start on the heels of the French New Wave.

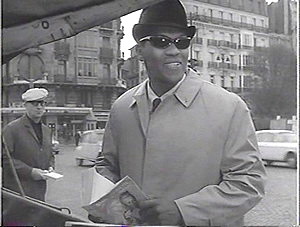

In the 1960s, van Peebles was invited by Henri Langlois to show his short films at the Cinémathèque Française, and presumably it was there that he learned more about the French film industry — in particular the funds available for first time directors, and the general desire to see young directors get their start on the heels of the French New Wave.[38] In order to access these funds, van Peebles became a French writer, writing for newspapers, and eventually writing five novels in French.[39] In 1967, using French funding, he made the fiction feature, Story of a Three Day Pass. This film was made in the style of the French New Wave but with a story about race and U.S. Empire rather than young Parisians on the lam. The film follows a U.S. soldier stationed in Paris who falls in love with a white Parisian woman and in turn, gets disowned by his fellow soldiers who report him to his captain. The captain rescinds his three-day pass and restricts him to the barracks for miscegenation; in this regard, it is worth noting that van Peebles was married to Maria Marx at the time, a white German woman with whom he had several children. Not only did the film receive critical acclaim abroad, it also played at the San Francisco Film Festival, where it received Hollywood attention. The great irony of van Peebles’s success at the festival in the city where he first started making films, however, was that he attended as the French delegate, championed by festival director Albert Johnson, who was both an advocate for African American filmmakers and a critic with interests in both global art cinema and third cinema.[40] As a result, his transnational movement explains how van Peebles addressed Donalson’s second point, “the lack of a power base by blacks in the business of filmmaking,” since the film’s critical acclaim allowed him to enter the Hollywood studio system proper with Columbia’s Watermelon Man.

While he was able to successfully parlay his work on Three Day Pass into making Watermelon Man, working in the studio system proved deeply unsatisfying for van Peebles. As someone who envisioned himself as an auteur, moving from a context that supported his creative vision (France in the 1960s), he now faced the restrictions of the U.S. studio system. The film follows Jeff Gerber, your average white suburban insurance agent, who wakes up one morning black. Eventually, Gerber leaves the insurance agency that has been exploiting black communities and forms his own company that serves these same communities. The screenplay was originally written by Herman Raucher, who considered the screenplay to indicate his participation in the civil rights movement. He penned the story to lampoon his liberal friends who were liberal regarding race only on face value, not unlike the theme of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. In partial conflict with Raucher’s original vision, van Peebles changed key plot points, however, taking the story away from an affirmation of American exceptionalism of the kind seen in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Watermelon Man was another critical, and this time financial, success. Because of his success as a studio director, Columbia offered van Peebles a three-picture deal. As the story goes, instead he made Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.[41] In the following sections, I will examine the way he brought his experiences in France working as an auteur to bear upon the restrictive studio system. However, ultimately it was his desire to work outside of these restrictions that prompted him to move from his “first cinema” film to his “third cinema” film with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

Stationed in France: Story of a Three Day Pass and the emergence of an auteur

With its focus on U.S. race relations, however, it makes use of features commonly associated with the French New Wave in a way that suggests it simultaneously stands apart from that film movement.

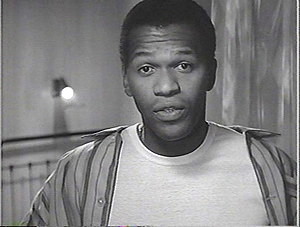

Story of a Three Day Pass details a short period of time in which an African American soldier Turner (Harry Baird) receives a ‘three day pass’ or off-station leave while stationed in France, during which he meets the white Parisian Miriam (Nicole Berger) at a jazz club. They begin a romantic relationship, which is cut short when they are caught vacationing on a beach by Turner’s fellow soldiers. The mere suggestion of miscegenation becomes enough for Turner to have his three-day pass revoked. The film resembles other films in the style of the French New Wave, unsurprising since it was made in France using first-time director state funding, French crews, and French talent. With its focus on U.S. race relations, however, it makes use of features commonly associated with the French New Wave in a way that suggests it simultaneously stands apart from that film movement. Through van Peebles’s editing and sound design, the film makes an anti-colonial argument regarding the use of colonized peoples as troops by revealing a biopolitical apparatus within the United States military that restricts and controls the rights and actions of African American soldiers.

I define Story of a Three Day Pass as being ‘in the style of’ the French New Wave because van Peebles is an outsider and latecomer to the wave’s boom in the late 1950s and early 1960s, while I also want to acknowledge how the film’s aesthetics are informed and made possible by the French New Wave as a predecessor. I am also careful to disentangle van Peebles’s own aesthetic interventions here from the French New Wave, such as his use of music that carries across all of his films. At the same time, van Peebles’s development as an auteur was made possible by his emerging from an auteur-friendly industry and he incorporates a set of qualities that might be thought of as a nod to young French directors that came before him. In the film, after the soldier receives his three-day pass, Turner wanders the streets of Paris like one of François Truffaut or Jean-Luc Godard’s aimless characters, visiting book vendors on the Seine, chasing girls, drinking Byrrh at a café, visiting burlesque theaters and dance halls. These sequences are shot in a fragmentary way, on location in the streets, with sudden cuts and close-ups amidst crowds on sidewalks or in clubs. The sense such filming and editing gives is that Turner himself has stepped into the same culture that the French New Wave depicted earlier. In this way, Turner’s physical exploration of the city is accentuated by the film’s aesthetic reflection on an earlier film tradition that similarly explored the city. Of course, the crew is also mainly French, and lead actress Nicole Berger is a French New Wave veteran, having previously acted in films by Eric Rohmer, Godard, and Truffaut. What characterizes this production process as different from a French New Wave film is that van Peebles consciously injects Turner’s racialized psyche into the film through his interaction with French characters, as well as through editing and sound design.

Linking U.S. race politics to the French New Wave constitutes van Peebles’s first transnational move … but even more significantly he addresses the global politics of the U.S. Empire through the film’s critical consideration of the military use of African American soldiers.

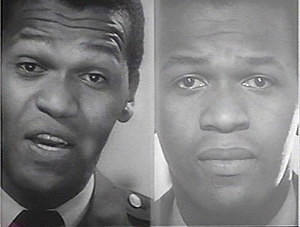

Linking U.S. race politics to the French New Wave constitutes van Peebles’s first transnational move, from which my article takes its title, but even more significantly he addresses the global politics of the U.S. Empire through the film’s critical consideration of the military use of African American soldiers. Just a year prior to van Peebles making Story of a Three Day Pass, the Black Panther Party called for “all black men to be exempt from military service,” for the reason that they should refuse to “fight and kill other people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized.”[47] Such an argument situates African Americans as colonial troops. In this light, a politics of global, anti-colonial solidarity would call for withdrawal from the operations of the U.S. Empire’s military interventions. A year later, Story of a Three Day Pass makes a similar argument in this respect. The film begins with Turner having a conversation with himself in the mirror about a potential promotion he might receive, but the film formally fragments Turner, first via sound design, and then by visually fragmenting his self through two, simultaneous frames. Turner’s psyche takes on a slightly different voice, accentuated by a hollowness that seems to mark it out as not physically present — although curiously enough, the ‘disembodied’ voice is the one on the left in the image I include here, which is not underexposed like the ‘real Turner’ on the right. The disembodied voice tells Turner, “Yeah, you’ll get [the promotion]. Yeah you’re pretty sure to get it … Uncle Tom.”

This moment is the first in a series of conversations Turner has with his self and demarcates the central concern of the film: his role in the United States military as an African American, including what is expected of him in terms of his future opportunities and also in terms of the way he is allowed to interact with the local population in France.

These scenes where Turner’s psyche splits and he speaks to himself in this manner are literal manifestations of van Peebles’s argument that “the white man has colonized [African American] minds.”

The script’s focus on Turner’s integration into white French society alongside his psychic acknowledgment that such integration is impossible continues throughout the film. As he explores the city, he runs into other black communities, but while he waves to black people in mutual acknowledgment, he does not join them in conversation. The emphasis on these moments reminds the viewer that this is not a simple question of confidence for Turner, but a racially enforced relation between a white society with a history of colonization and a visitor from a country that understands its relation to race quite differently. When Turner returns to his hotel after asking Miriam to go to the beach with him, his split psyche emerges again. He tells himself in the mirror, “I’m sure she’ll come,” to which his other self replies, “Don’t count your chickens before they’ve hatched, baby. She ain’t coming.” Earnestly he tells his other self to the mirror, “I hope she comes.” These scenes where Turner’s psyche splits and he speaks to himself in this manner are literal manifestations of van Peebles’s argument that “the white man has colonized [African American] minds.”[48]

Frantz Fanon made an argument about such a fragmenting of subjectivity earlier in Black Skin, White Masks (1952), based on his experience travelling from Martinique, a French colony, to France to study medicine. Turner’s move from the United States to France, however, is almost the opposite of Fanon’s transition from Martinique to France. While both find a metaphysical split as they interact with white populations, in Story of a Three Day Pass, Turner does not find this split in France, but brings it from the United States with him — and at times he seemingly finds this fissure mitigated in his interaction with French locals. Fanon describes this psychic split: “the Negro has been given two frames of reference within which he has had to place himself. His metaphysics, or, less pretentiously, his customs and the sources on which they were based, were wiped out because they were in conflict with a civilization that he did not know and that imposed itself on him.”[49]

In Turner’s case, the civilization he finds himself in conflict with is white American civilization at large, and more specifically United States military command. While his psyche often comes across as antagonistic, intervening when Turner behaves too optimistically, a later conversation with Miriam illustrates that he acknowledges his racialized role as, following black radical politics, a colonial soldier in the U.S. Empire. When Miriam says, “I like your captain. He must be nice to give you a three-day pass and a promotion,” Turner replies, “No no no, he thinks I’m a good negro.” “Good negro, what is it?” she asks. He explains: “To my captain? That’s a negro you can trust. Trust to be cheerful, obedient, and frightened.” This kind of reflection, then, is also brought to the fore on the soundtrack through the audio collaboration between Mickey Baker and van Peebles.[50]

While most of the soundtrack is made up of Mickey Baker’s jazz guitar, van Peebles intervenes with discordant, jarring notes that often punctuate what would otherwise be a relatively standard non-diegetic soundtrack. While, in visual terms, quick cuts and sudden close-ups were used previously in the sequence in which Turner explores Paris, these jarring cuts are even more pronounced halfway through his trip with Miriam to the beach. During this sequence, sudden cuts become freeze-frames while guitar riffs override the soundtrack. The film freezes on close-ups of Miriam’s thighs or calves as she stretches out in the car, marking the sexual tension of the scene. During the sequence, the narrative cuts back and forth between the sexualized images of Miriam’s body and her smiling face, or as she explains something to Turner, with shots of the landscape they pass through as well.

|  |

| A close up of Miriam’s thighs as discordant guitar chords suddenly cut through the previously upbeat jazz underscoring. | The film begins to cut back and forth between suggestive shots of Miriam, and her talking, engaged in conversation with Turner. |

|  |

| Each time the film cuts to her thighs or ankles, the discordant guitar once again cuts through the soundtrack. | Interspersed throughout are shots of countryside, until they reach the ocean. |

When landscape or Miriam’s face appears, the soundtrack provides jazzy, upbeat underscoring, accentuating their excitement at their impromptu beachside trip. While the jarring cuts and chords have a relatively straightforward narrative purpose, suggesting that this is a romantic affair and not merely a trip with a new friend, van Peebles pushes this further when they consummate their budding relationship. Beyond Story of a Three Day Pass, this style also marks out an aesthetic strategy that van Peebles will apply across all three films discussed in this article. While each iteration suits the individual film, it illustrates the director’s early interest in manipulating the commercial practices of continuity editing in order to introduce a critical race politics.

The pattern of radical interjection develops in the direction of a critical race politics in Story of a Three Day Pass during the first romantic encounter between the couple. While they are having sex in their hotel room, the film suddenly begins to cut between their embrace and far-removed scenes, first the seeming fantasies of each, and then actual events in the world accompanied again by the discordant guitar. As the couple lay down together on the bed, the camera first zooms into Turner’s head and the film cuts to a fantasy sequence where Turner is a member of the French aristocracy, complete with fancy dress and a countryside manor, which leads into a romantic encounter with Miriam. Next, the camera zooms into Miriam’s head, and the following fantasy sequence depicts her being captured by an African tribe, which leads to Turner showing up to initiate a romantic encounter.

|  |

| Miriam being captured in her sexual fantasy. | Turner appears in Miriam’s fantasy. |

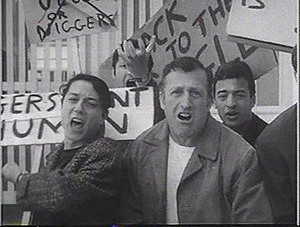

Turner’s fantasy is accompanied by classical strings, whereas Miriam’s is accompanied by a tribal drumbeat, but as the film returns to their real lovemaking, the film’s previous underscoring resumes. This time, however, sudden cuts interject less fantastical images, as the jarring guitar returns from the previous scene. Whereas the fantasy worlds were coherent, the interjection of images from the historical world are introduced as a disruption. These images include found footage from World War II, meat being chopped, police brutality, dead bodies being carried on a plank, military maneuvers with helicopters and troops, and a reenacted race protest.

|  |

| Meat being chopped, immediately after Turner and Miriam begin their lovemaking, which foreshadows the brutality against actual human bodies that follows. | A man wearing a military uniform kicking a civilian onto the ground, intercut with Turner and Miriam’s lovemaking. |

|  |

| A civilian being beaten with a baton, intercut with Turner and Miriam’s lovemaking. | A corpse being carried on a stretcher, intercut with Turner and Miriam’s lovemaking. |

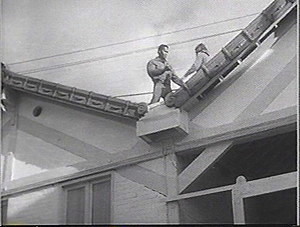

In the last sequence, with the reenacted race protest, Turner whistles from a rooftop and the camera tilts and pans to show him beckoning to Miriam, as she comes forward to kiss him, suggesting both acknowledge that their tryst will upset certain populations (and that, perhaps, they don’t really care). While their diegetic sex is uninterrupted and seemingly pleasurable for both, the disjunctive editing riddles their lovemaking with the history of colonialism and its aftereffects. This editing suggests, like Turner’s ‘other’ self, that his present relationship is too good to be true.

… the film’s conclusion returns to the critical race politics informed by van Peebles’s formal interventions — through the splitting of the self through the use of two frames, the discordant guitar riffs, and his intercutting history into their passionate romance.

While together, Miriam and Turner’s relationship seems as if it might end along the happy lines of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, with a relationship freed from, or at least relatively unencumbered by, social norms, but the film’s conclusion returns to the critical race politics informed by van Peebles’s formal interventions — through the splitting of the self through the use of two frames, the discordant guitar riffs, and his intercutting history into their passionate romance. After Turner’s fellow soldiers see Miriam and Turner together at the beach, Turner bemoans, “I guess I just lost my promotion.” Miriam, seeming not to understand the seriousness of racial politics in the United States, remains upbeat, suggesting that the other soldiers won’t report anything to his captain. Miriam seems completely smitten with Turner, and in a passionate monologue tells him that she’s decided she’s “not going to be ‘sick’ anymore,” unless with him — sickness being her excuse for leaving work in order to go to the beach. Eventually, she wins him over and he agrees, “You’re right, they probably won’t say anything.” This upbeat note is cut short by Turner’s psyche, who glibly decries, “I’m not so sure!” The film instantly cuts to Turner’s captain demoting him and restricting him to base.

|  |

| Turner’s fellow soldiers, upon seeing him with Miriam – the sequence ends with one of the soldiers saying ominously, “But we’ll tell everyone we saw you.” | Turner’s expression after meeting his fellow soldiers, and saying, “I guess I just lost my promotion.” |

This conclusion cements the African American soldier’s role in U.S. Empire in line with the Black Panthers’ decree: African Americans are situated as colonial troops, part of the U.S. military arm but biopolitically separate from its sovereign citizens. At the same time, van Peebles takes his conclusion one step further. Through a stroke of luck, a contingent of African American women show up to tour the military base and lodge a plea with the captain, so Turner gets his leave reinstated. As soon as one of the women hands him his papers, he immediately makes a dash for the base telephone and calls Miriam’s workplace, which informs him that Miriam is “not here … she’s sick.” With this devastating ending, the film suggests that the viewer should have known all along, already clued in by all of van Peebles’s hints in the form of disjunctive sound design and editing. Turner’s psyche steps in one last time to say, “Hey baby, I could’ve told you.” He replies, “Fuck you,” and tosses himself on his bunk. With this conclusion, van Peebles maintains a radical politics rather than return to American exceptionalism through a liberal belief that everything would work out in the end. Here, the “Glory of Love,” to cite Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner’s ending theme, is not enough to end racial prejudice.

To read the full article, including the examination of Watermelon Man, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song go to Jump Cut, where this article first appeared.

About Matthew Holtmeier:

I write and edit video essays about film, the environment, and weird fiction.

I earned my PhD in Film Studies at the University of St Andrews and currently teach at East Tennessee State University as Associate Professor and Co-Director of the Film and Media Studies Minor. I am also on the editorial board of the journal Film-Philosophy and conference manager for our annual conference.

Read more at MatthewHoltmeier.com

Notes

1. Van Peebles, Melvin Van, The Making of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (New York: Lancer Books, 1971 [1972]), 14. [return to page 1]

2. Van Peebles, The Making, 14-15.

3. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, [1975] 1986); Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, [1980] 1998); Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, [1985] 1989); Deleuze, Gilles, “One Less Manifesto,” in Mimesis, Masochism, and Mime: The Politics of Theatricality in Contemporary French Thought, ed. Timothy Murray (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

4. Deleuze, Towards a Minor, 17.

5. Bates, Courtney E.J., “Sweetback’s ‘Signifyin(g)’ Song: Mythmaking in Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 24 (2007), 172. The mainstream in this citation refers to “white action and Western film narratives.”

6. Deleuze, Towards a Minor, 17.

7. Young, Cynthia, Soul Power: Culture, Radicalism, and the Making of a U.S. Third World Left (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 6.

8. Dargis, Manohla and A.O. Scott, “Watching While White: How Movies Tackled Race in 2016,” The New York Times, January 5, 2017.

9. Rana, Aziz, “Colonialism and Constitutional Memory,” U.C. Irvine Law Review, Vol. 5, Iss. 2 (2015), 268.

10. Creedal politics here refers to an insistence on the framing of the United States as free and equal from its founding, in line with its constitution, which obfuscates contemporary structural inequalities.

11. Young, Soul Power, 3.

12. For example: Killer of Sheep (1977), Daughters of the Dust (1991), Paris is Burning (1990). All significant films representing marginal communities in the United States, though perhaps not with such an aggressive politics as Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

13. Van Peebles, The Making, 12.

14. Van Peebles, Melvin, “Lights, Camera, and the Black Role in Movies,” Ebony, November (2005), 96.

15. Van Peebles, The Making, 15.

16. Through Sidney Poitier’s oeuvre, for example.

17. Aziz, Rana, The Two Face of American Freedom (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 13.

18. This framing was part of the larger discourse surrounding black power. Rana, “Colonialism and Constitutional Memory,” 282.

19. Lipset, Seymour Martin, The First New Nation (New York: Basic Books, Inc. 1963), 2.

20. Lipset, The First New, 15.

21. Rana, Aziz, “Race and the American Creed: Recovering Black Radicalism,” N+1 Magazine, issue 24 (2016): https://nplusonemag.com/issue-24/politics/race-and-the-american-creed/

22. Newton provided his own revolutionary analysis of the film: “He Won’t Bleed Me: A Revolutionary Analysis of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” in To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton (New York: Random House 1972), 112-147.

23. Donalson, Melvin, Black Directors in Hollywood (Austin: University of Texas Press 2003), 3. [return to page 2]

24. Van Peebles, “Lights, Camera,” 94.

25. Van Peebles, “Lights, Camera,” 92.

26. Getino, Fernando and Octavio Getino, “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World,” in New Latin American Cinema, ed. Michael T. Martin(Detroit: Wayne State University Press 1997), 42-43.

27. Getino, “Towards a Third,” 42.

28. Getino, “Towards a Third,” 54.

29. Getino, “Towards a Third,” 42 – thought perhaps least so in Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, with its taciturn protagonist, but this is also the film most closely aligned with third cinema. Nonetheless, the film provides Sweetback’s history as a way of explaining his subject-position, and details the process of his becoming-political.

30. Gabara, Rachel, “Abderrahmane Sissako: Second and Third Cinema in the First Person,” in Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, eds. Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2010), 321.

31. Holtmeier, Matthew, Contemporary Political Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2019), 80.

32. Comolli, Jean-Luc and Paul Narboni, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” in Cahiers du Cinéma: Volume 3, 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation, ed. Nick Browne (London: Routledge 1996 [1990]), 58-67.

33. Comolli, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” 60.

34. Comolli, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” 62.

35. Comolli, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” 62-63.

36. Comolli, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” 62.

37. Gerhardt, Christina and Sara Saljoughi, 1968 and Global Cinema (Detroit: Wayne State University Press 2018), 2, 7.

38. Graham, Peter, “New Directions in French Cinema,” in The Oxford History of World Cinema, ed. Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 576. [return to page 3]

39. Un Ours pour le F.B.I. (1964), Un Américain en enfer (1965), Le Chinois du XIV (1966), La Fête à Harlem (1967), and La Permission (1967).

40. Johnson brought an international component to the San Francisco Film Festival, would later go on to help establish the Oakland Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame (which inducted van Peebles), and later would teach African American and Third World film at Berkeley, a locus of many of the issues discussed in this article. For a brief list of his many accolades, see: “Remembering Albert Johnson: Black Scholar, Critic, and Academician” by John Williams in The Black Scholar, Spring 2003, 33.

41. My colloquialism here refers to the establishment of van Peebles legend through his own autobiographical account in The Making of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, as well as his son Mario van Peebles’ later retelling in the film Baadasssss! (2003). He recounts other aspects of this story in many interviews, which add to the legend as well.

42. Van Peebles, The Making, 68.

43. Wayne, Mike, Political Film: The Dialectics of Third Cinema, (London: Pluto Press, 2001), 23.

44. Van Peebles, The Making, 14.

45. Van Peebles, The Making, 12.

46. “Towards a Third Cinema” by Solanas and Getino, “For an Imperfect Cinema” by Espinosa, and “An Aesthetic of Hunger” by Rocha.

47. Rana, “Colonialism and Constitutional Memory,” 284. Further citation in Heath, Louis G., Off the Pigs! The History and Literature of the Black Panther Party (Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1976), 249.

48. Van Peebles, The Making, 12.

49. Fanon, Frantz, Black Skin, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 2008 [1958]), 257-258.

50. Van Peebles is referred to as “Head Nitwit in Charge” in part of the musical credits.