By Chimezie Chika

I

I once came across a tranche of images of African hairstyles made by European colonial photographers—the likes of Northcote Thomas and J.T. Basden—in the late 19th and early 20th century Nigeria. That sultry encounter with the coiffed and dreaded kinks of my ancestors has shaped my perception and appreciation of the originality of African hair. Such was my feelings then when I encountered a photography series titled “Yoruba hair” by Edirin John Duvwiama, better known as John Bliss. Duvwiama had decided to embark on this project after he found himself thumbing through an African women’s hair magazine at a hairdressing saloon in Lagos.

“Yoruba Hair” shows us a series of headshots of Yoruba women with varying Yoruba hairstyles. What is fascinating about these photos is how clearly they capture the accouterments of beauty and cultural values. Essentially, we can contrast these hairstyles against other styles across Africa and reveal where one culture places the most value and the hidden meanings that reside thereof. Each of the shots shows the subjects’ heads from the back, from the sides, and from above, but never from the front. Perhaps, in taking the focus away from the faces of these women, Duvwiama is letting us focus on the hair, to draw out the distinct beauty that comes from their uncommon aesthetics in a time when the discourse of African hair has been overtaken by a large economic enterprise pitching the merits of wigs, synthetic weave-ons, and other artificial hair accessories to women. It appears, even, that social media self-projection of beauty has driven the hair market into the level of a status symbol, a situation in which we now see African women flaunting their ability to purchase expensive “Bone-straight” Brazilian or Indian hair, while natural hair is frowned upon as an undeniable sign of poverty.

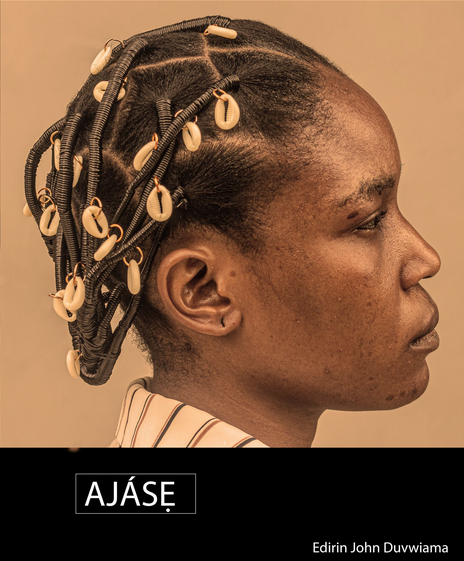

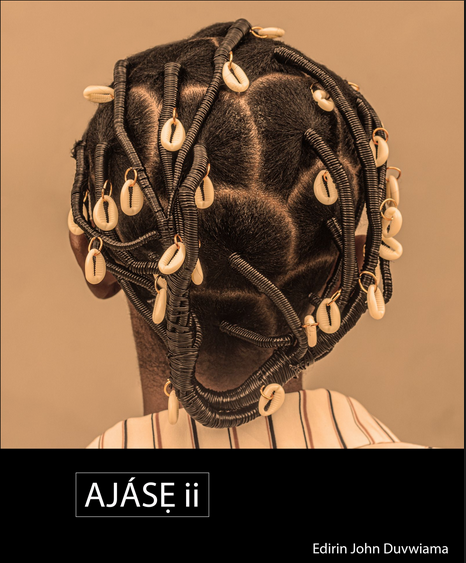

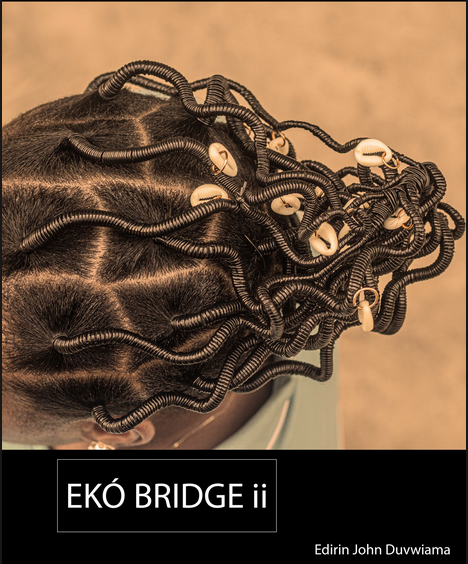

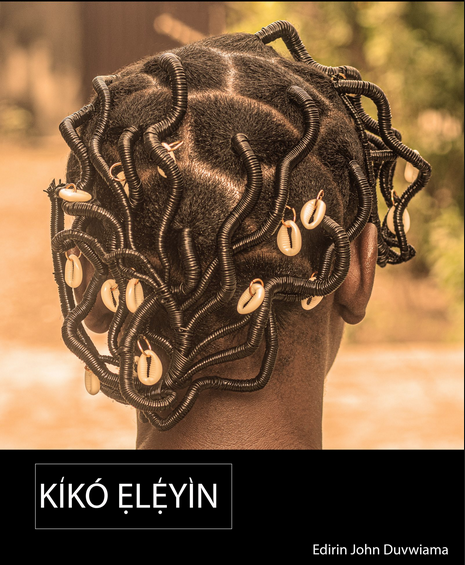

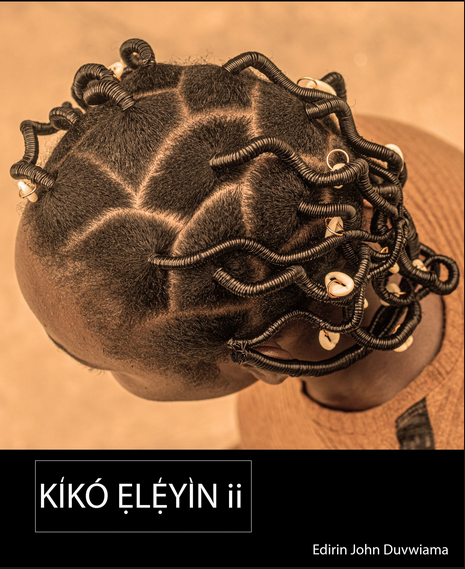

In these photos, Duvwiama brings back for us the pristine beauty of natural hair and the dexterous manner of its traditional braiding and coiffing. In the photo, “Ajase”, we are given two views of a woman’s hair braided with rubber trade and decorated with artificial cowries. This hairstyle was popular before the social media-saturated world that came to be the norm from the 2010s onward. The main feature of the hair is the deft pathways created in the hair, while it’s being parked together, bunched together in dense thickets. This type of hair could range from the simple to the complicated. A more complicated version of the hair is what we find in “Eko Bridge”, which features a woman’s hair in three photographs showing the profile view of her hair, the back view, and the top of her head. While it is the same hair as “Ajase”, we find that the different rubber-treaded braids are denser and packed in a stiff, upstanding way, which gives its beauty a severe look. In the same manner, “Kiko Eleyin”, shows the head of another girl with same hair type. But this time, the thicket of braids is packed in a kind of double pony.

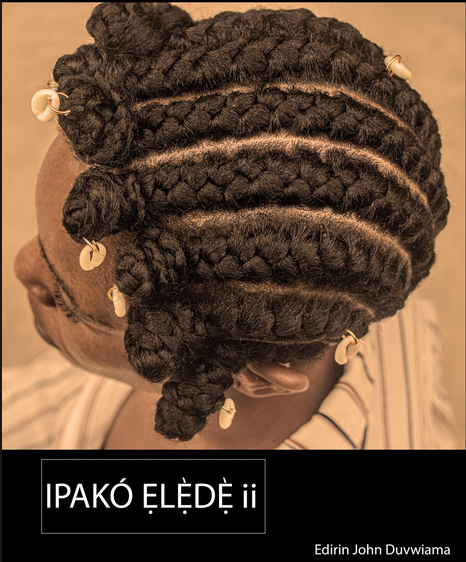

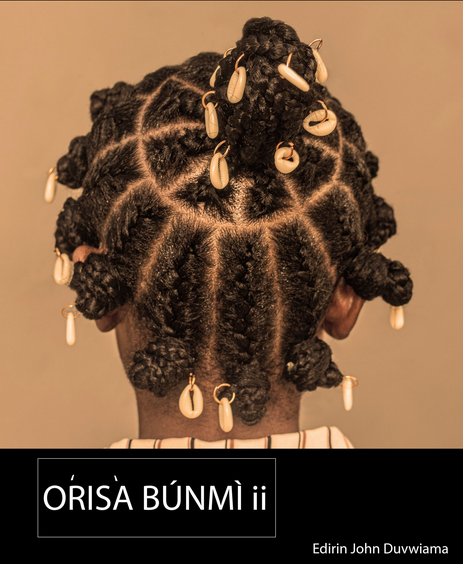

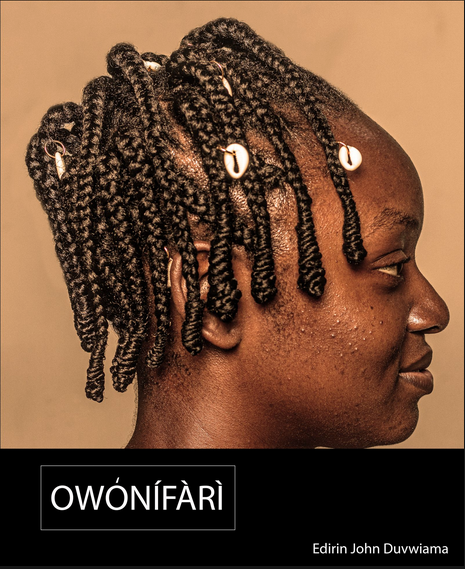

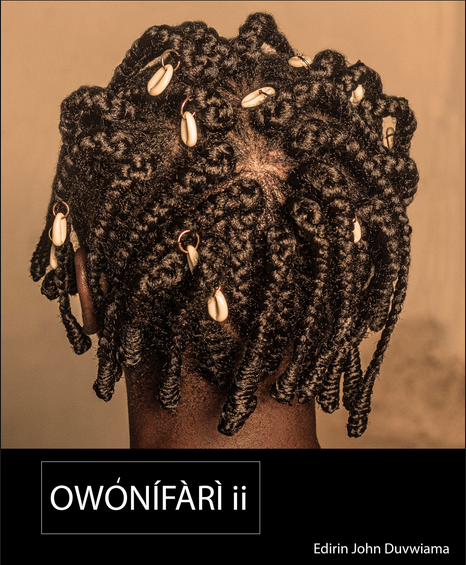

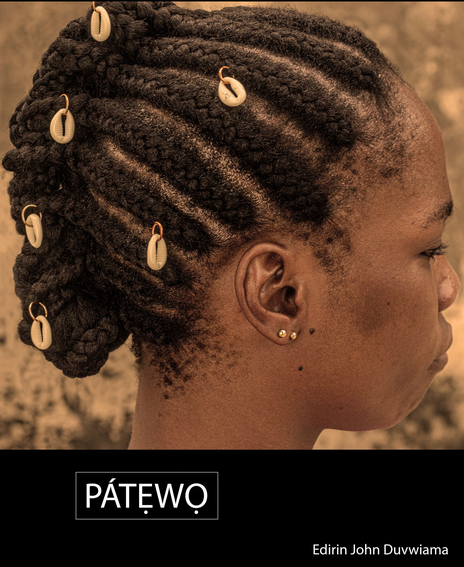

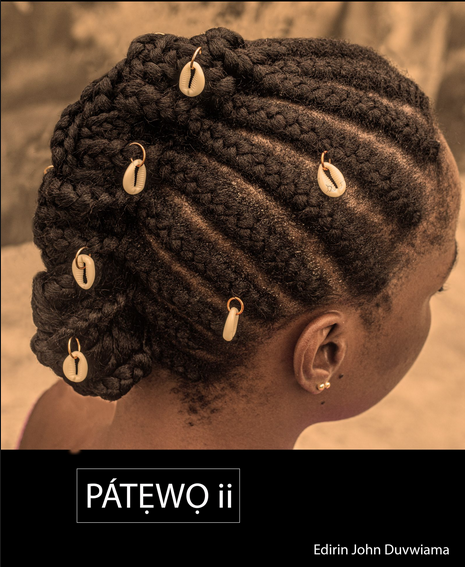

Other styles featured in the series is the skull weave. In one, such as “Ipako Elede”, the weaves are large, each ending with knots that collectively form a semi-circle on the girl’s forehead; another like “Kolese” reverses the style, placing the knot below, at the nape of the neck. “Koroba”, “Koste”, and “Owonifari” show a flamboyant traditional style that resembles Marlian dreads. The uniqueness of the stunning hairstyle in “Patewo” is that it merges the best qualities of hairs like those captured in “Kolese” and in “Koroba”. The lovely downward-styled hair on a little girl in “Orisa Bunmi” also has this quality. Going through this leaves us in no doubt as to the beauty and creativity involved in making African hairstyles—and the complex skillset involved. Duvwiama’ lense particularly gives us details of these hairstyles in lucid, untouched colour.

II

What he seems to bring when his lenses land upon the environments he encounters is empathy. He often turns his gaze to the ordinary and the silent.

Duvwiama has stated that his photography explores the intersections of human experiences, architecture and the environment, inviting viewers to contemplate the stories and emotions embedded within. The capturing of the environment and architecture is a subject in Duvwiama’ work. What he seems to bring when his lenses land upon the environments he encounters is empathy. He often turns his gaze to the ordinary and the silent. And in this, we also feel his connection to these places. His photos of architecture and environment are clearly demarcated into photos of Lagos, Nigeria, where he hails from and Derby, England, where he attended university.

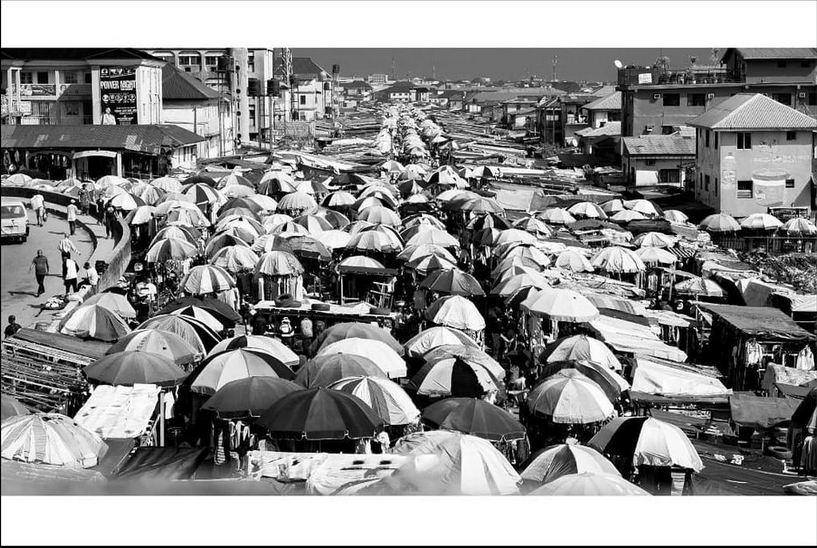

In the former, the photographs feel more authentic, artistically aware, and relatable. One photograph is a close aerial view of a market in Lagos. The viewer is drawn first to the dozens of umbrellas that cover the middle of the frame, like foraging chickens. The margins of the frame are dominated by storey houses and a section of road—a bridge, possibly, judging by how the edge of the concrete kerb seems to be a little below it—where people are passing. The photo is the quintessence of the hive of activity for which Lagos is known for.

Another of the Lagos photos shows another inexorable identity of city of Lagos—that of water and the activity around water. (As a city surrounded by lagoons, Lagos has a large fishing community.) In close-up, the photo captures a magnificent art installation on a roundabout on the road to Ikeja. The installation consists of canoes placed side by side in an upright position on a concrete base to form a circle. On the outer reaches of the frame, a blurred green road sign announced that the road led to Ikeja. And we may not have known what time of the day it is, but for the headlights of the cars passing on the left edge of the frame and the amber of the sky.

The photos taken in England (mostly of Derby University)—apart from the metaphors of silence, loneliness, and desertion—are decidedly bland in comparison. They seem to have neither life nor artistry in them. They are like show-off pictures taken by tourists. In one, we see the frontage of a tower, but it is not composed in such a way as to draw our attention to something extraordinary about it—a missed opportunity. The photo would be better in monochrome, to begin with. In another, an ochre and brown classical building fills the frame, with a large portico and pediment.

IIl

One of the most striking photos in Duvwiama’ collection is a black-and-white photo showing a silhouette of two figures. Apart from them, we also see the outline of trees. But the majority of the frame is dominated by the sky where a flight of egrets are caught in the circular shadow of the sun, a sign of evening. But we ask ourselves: what are those two figures (one is a child, on closer look) doing in that landscape at that time?

While there are no immediate answers we can deduce, from his work, that Duvwiama has an ever-so-slight fascination with the figure of the child. In short, two photos on his website riffs on the idea of “child protection”. This is not some social law in place to protect children. Duvwiama shows us two photos of pregnant women with pins attached to their clothes, where the bulge of the pregnant belly is. The idea, he notes, comes from a common myth in Nigeria which holds that putting a pin in the cloth of a pregnant woman protects the child from evil spirits or evil eyes. This is the norm in societies where congenital disabilities such as autism, down syndrome, and others are ascribed to evil spirits. From his language, Duvwiama clearly disagrees with this. His mere aim, it appears, is to capture that aspect of Nigerian culture. Interestingly, that stance also appears to be in opposition to the photo series he calls “The Ghost Series”. According to him, the photos symbolize for him the ephemeral and nebulous nature of life. But the photos we see are negatives that seem to have been altered somewhat by editing. Of these, the triple photos he calls “Ghost Baby” are most interesting (although I found “Ghost Mother” to have a certain aura of mystery and spirituality, which comes from the Gothic woman in white symbol). The baby’s nondescript figure is captured at different points of remove from the lenses. We can only identify its silhouette in a shower of aquamarine, so that the baby appears more like a doll than anything else. Duvwiama notes that, for him, the ghost baby represents lives that never came to be. For me, I think it is enough to let photos be without ascribing interpretations to them. Photography is enough in itself for existing, and so are the many advocacies of Duvwiama’ photography.

Chimezie Chika is an essayist, critic, and writer of fiction. His works have appeared in or forthcoming from The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, Channel Magazine, and Afrocritik. He currently lives in Nigeria.

Categories: featured, Photo Essay, photography