By Chimezie Chika

Viewing Ololade Koleosho’s photographic work, there is a point when what the viewer has seen translates into a response that could be quite inadvertently emotional. It creeps up on you as you go through stories of miscarriages, slum living, love, and palmistry. And the question that intersects these is, at what point does destiny and unpleasant human outcomes converge? Are our problems uniquely ours—that is, set out for us as part of some divine predetermination—or are they resultant effects of dysfunctional societies and broken systems?

Koleosho seems to particularly want to demystify any stigma surrounding the condition of single motherhood in Nigeria through her photography. She believes that the lives of single mothers dwells somewhere on the “delicate balance between struggle and celebration.” It is an apt way to chracterise the fundamental struggle of single mothers in a country like Nigeria; their urgent need to ensure the survival of their children all alone while simultaneously drawing some inspiration from motherhood.

Her recent black-and-white photography series, “A Single Mum Christmas” (2024), attempts to capture these struggles through visual storytelling. A photo from the series titled “Mommy Oyebola” features an elderly woman and a boy. The boy’s back is turned to the camera, but even then, we see that his faceless anonymity does not hinder his closeness to the woman whose face is turned sideways to him in a gesture of motherly attention. The duo’s festive attire contrasts sharply with their austere surroundings which had a clothesline on the far left and debris around the unplastered walls of the fence. Near those selfsame walls is the blurred figure of a man carrying a backpack. A journeyman? A labourer?

The economic downturn in Nigeria in the last couple of years has been hard on all economic classes, but the situation is even worse for families of formerly middle-class and lower-class individuals who have all descended down to the boundaries of proper poverty. For single mothers, who are singularly involved in this strenuous chain of survival, one can only imagine how hard it has become to keep their families afloat. The idea behind this series then is that joy and celebration—read respite—can be found amidst hardship. Another photo titled “Mommy Comfort” features another elderly woman and her grown-up daughter. While the mother, who sits to the left, faces the camera; her daughter’s striking back is turned to the camera, so that the viewer begins to wonder what her face might look like. The background is the same as in “Mommy Oyebola”. In a second version of the photo, the daughter is leaning on the woman’s shoulder, as if seeking comfort in her motherly frame. The stool upon which they are sitting has a new space where the daughter has vacated after having moved closer to her mother.

The single tone of colour in these photographs are the Christmas red hats and the red-or-green frills that the subjects wear. These photos are marked also by the duality of their human content: in them there is a tacit interaction between the single mothers and their offsprings—each mother and child representing different ages and generations. Both singularly and as a collective. This is how we find that the next photograph, “Mommy Adeniji”, features a younger woman carrying her toddler while standing. In one photo, she’s facing the camera while the toddler in her arms backs the camera; in another, she is looking at the camera from a sideways posture, but the child’s head is still turned away, as if being shielded from dangers lurking beyond.

The only photograph in the series that breaks the mother-and-child binary is “Mommy Akpan”. There are two photographs and they both feature the same middle-aged woman surrounded by six children. They appear to us as not so much her children as a clan she presides over with love and protection. The children are standing three on either side of her, their bodies angled in such a way that they not only seem to be turned away from the camera, they also seem to be performing a ritual of paying respects, as if they are about to begin something new.

The Other Economy

The Christmas series, with its capturing of motherhood and struggle, seems to hark back directly to some of Koleosho’s earlier photographs centered on women and poverty. The one feature of these photographs is the emotional and political undercurrent that runs through them. Are people poor out of choice, destiny, or due to their country’s political mismanagement? These are questions Koleosho’s work seems to ask repeatedly.

The two photographs titled, “The Female Masters of the Sea” (2008), are most likely taken in Makoko, the floating slum community in the Lagos lagoon. The photographs capture an elderly woman identified as Grandma Athoan and her granddaughter. In Grandma Athoan’s photo, we see her paddling a canoe towards a cluster of old wooden structures on stills. We only see her back, for she’s paddling away from us. Her Ankara clothes are as colorful as the plastic containers and gas cylinder on the other side of the brackish water. The photo of her granddaughter captures her idling on a boat in front of another boat. Her posture and expression is uncertain, as if she is about to do something we cannot ascertain. But she seems nonetheless at peace with her surroundings: a section of old wooden stilts propping a section of a house and plastic islands of floating debris on the brackish water.

In her notes, Koleosho reveals that the Athoan family owned four boats, which they operate like a second skin. Thus, it is clear that whatever we, as outsiders, might think of their condition, they appear to be making the most out of it. But if these low levels of economic existence are linked to destiny—destiny in the traditional sense—then the photographer seems to want to sleuth around that. Her photo series on palmistry, “Lines of Destiny” (2021), is a powerful project that incorporates both modern African reality and what may seem to be recondite beliefs that one’s state in life is decided by divine or spiritual ordering, that in the marks of a person’s hands lies the imprinted map of their life’s journey.

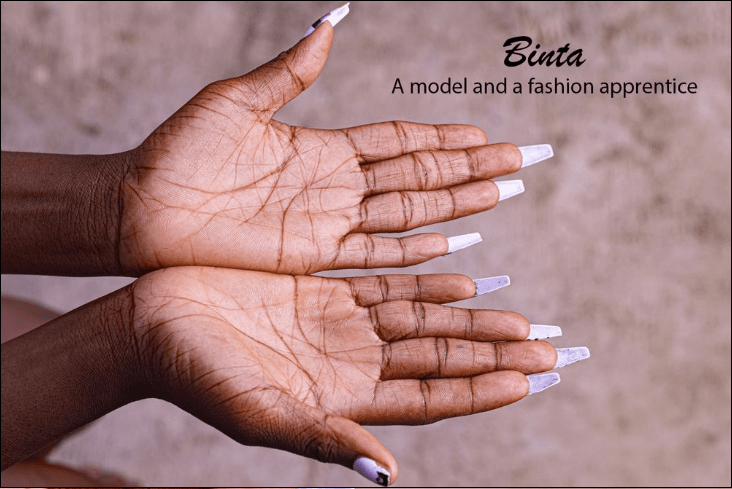

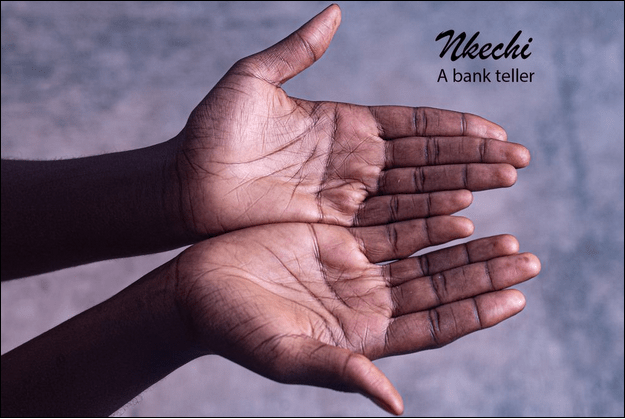

In this fascinating series, Koleosho juxtaposes pictures of the subject’s palms with their occupation. It is then left to us to try to read the connections between the two, if we are able to. But there are instances when it seems to us viewers that we can see when a subject has a clear-enough path, as in the case of Mr Godwin, a business owner who owns three businesses, or Nkechi, the bank teller: the lines of their palms seem to be clearer, deeper, and fewer. This is in contrast to Binta, a model and fashion apprentice, whose palms have several lines, large and small ones, thick and thin ones, crisscrossing and diverging all across her palms. Could this mean anything? Same could be said of Sheriff, a tricycle rider. Where do palms and destiny converge, if they do? The photographer herself seems to believe they do, as her statement reveals, but I do not have that certainty.

Love and Miscarriage

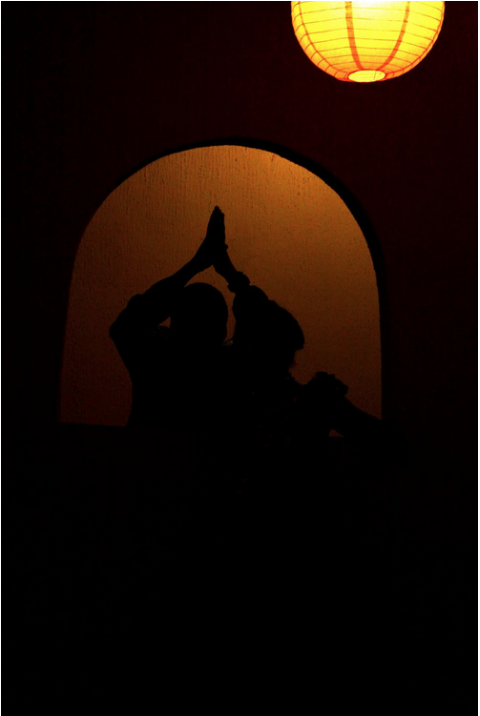

“Hand Crafted with Love”, another symbolically clairvoyant series that uses human hands to tell stories, is clearly connected to the palmistry series, but here our focus is directed to love with a series of photos of silhouetted hands against mostly sunset backgrounds. One photograph here, “When Two Has Become One 1” (2015), shows hands making the sign of love. “When Two Has Become One 2” and “When Two Has Become One 3” show other hands in almost the same shape. “2” makes the heart sign by cupping a setting sun in the horizon; “3” makes a sign that is closer to Kama Sutra than the traditional heart sign. In “When Two Has Become One 4”, we see the silhouette of two lovers in a yellow-lit doorway, with their hands linked above their heads, while the rest of the background remains dark.

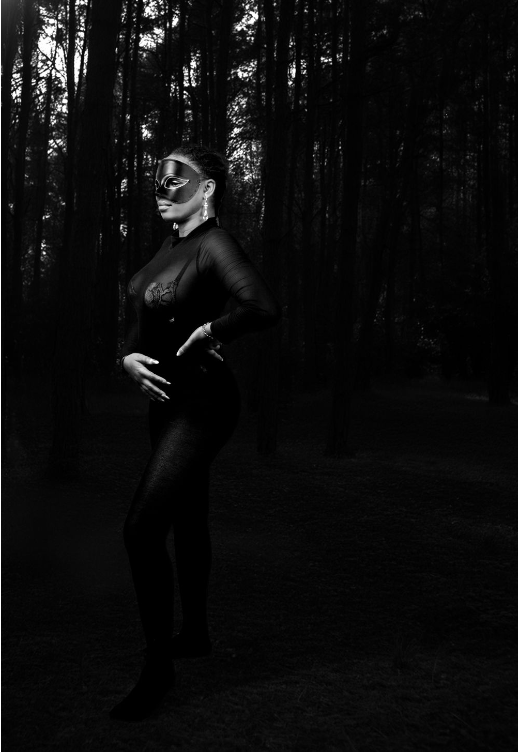

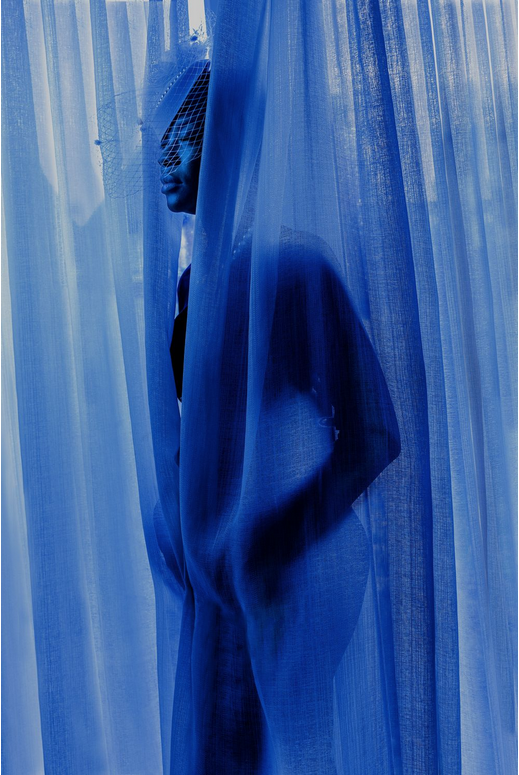

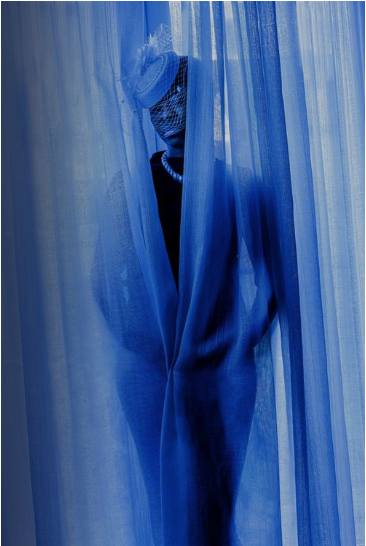

Another of Koleosho’s series, “Miscarriage” (2021), focuses on the more painful part of love’s aftermath for women. We will discover that each of Koleosho’s carefully curated pieces tells an aspect of women’s stories, from their confrontation with the hardships of single-motherhood to poverty, love, and miscarriage. Miscarriage is a deeper and more provocative topic, for in it, we may excavate health issues, insecurities, cultural stigma, among other things that plague women in Nigeria and Africa today. The subjects here, Sariyu and Lady Abeke, are all women grappling with the despair of miscarrying. The photographs of Lady Abeke, captured in a muted hue of blue shows, more or less, her permanent blue state of mind—her mood here seems to be a recurring echo of sadness and longing. Her story is equally as interesting as it is heartbreaking. Now 38, Abeke had married at 23 but had remained childless after 8 miscarriages and 2 stillbirths. Koleosho’s photography captures her mixed, dolorous emotions for always being seen with a pregnant belly in one instance and an empty one in the next. But the overarching questions that troubles us finally, based on the background of Koleosho’s photography are these: Is Lady Abeke’s condition her fault? Is it a congenital medical issue? Or is it part of her unknown destiny?

Chimezie Chika is an essayist, critic, and writer of fiction. His works have appeared in or forthcoming from The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, Channel Magazine, and Afrocritik. He currently lives in Nigeria.

Categories: featured, photography