By Simon Morley

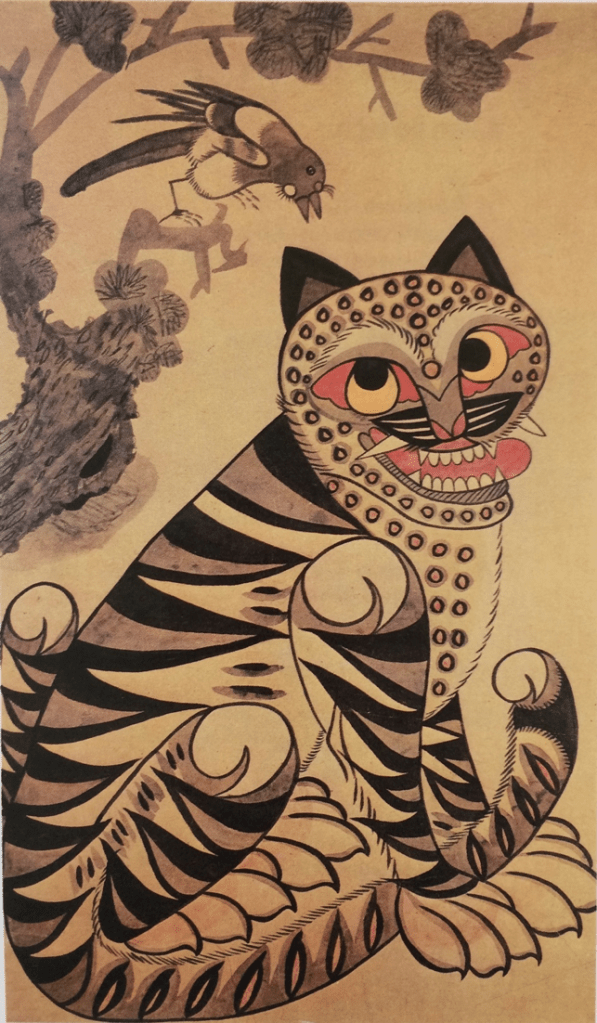

The strange animal, clearly outlined in black ink and bright colours against a blank background without any horizon line, sits in front of a pine tree. Its jaws are open, revealing a set of fang-like teeth and a pink tongue. Oddly, the pupils of the eyes are yellow rather than white, and it also seems to be cross-eyed, as one eye is looking straight up, the other to the side, giving it a decidedly demented, even ‘stoned,’ expression. After a moment, we realize that the creature is looking at the magpie perched on a branch of the tree. Maybe they are having a conversation. One wouldn’t say this creature is very frightening. In fact, the impression is rather endearing. From the evidence of the zig-zag striped coat, it looks like a very stylized depiction of a tiger, but then we notice that the chest is covered in leopard spots. So while this creature is certainly inspired by the real tigers that used to roam old Korea, it is actually a strange mythical beast. Why was it painted? And why it is coupled with a magpie?

This Magpie-Tiger painting is from 19th century Korea, and is an especially famous example of a specific genre within Minhwa (literally, ‘people’s art’), the most accessible kind of traditional Korean art, and therefore an excellent way to introduce Korean traditional culture to the wider world. The anonymous painter who made this delightful painting was not concerned with making a realistic imitation of a tiger or magpie. His goal was to create a visually striking image based on a fixed repertoire of themes with specific meanings and practical purposes.

Minhwa is characteristically optimistic. It aims to convey a world without sorrow and pain.

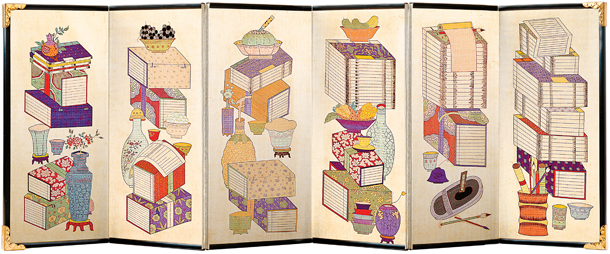

Minhwa is characteristically optimistic. It aims to convey a world without sorrow and pain. It is to be distinguished from the art of the nobility of the Korean Joseon dynasty, although it was also an intrinsic part of the lives of the royal court, and as such, Minhwa should not be confused with ‘folk art,’ in the sense of a kind of painting exclusively of the uneducated lower classes. Nevertheless, high culture in Joseon was dominated by Chinese cultural norms, and put a premium on intellectual and philosophical properties in art, and as a result, while Minhwa was part of the lives of the upper classes, it was denigrated as stylistically crude, and as excessively bound to primitive superstition. But it is argued that Minhwa actually displays more intrinsically Korean characteristics, which ultimately derive from folkloric influences that blend animistic shamanism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. As such, no other country has produced works comparable to Minhwa.

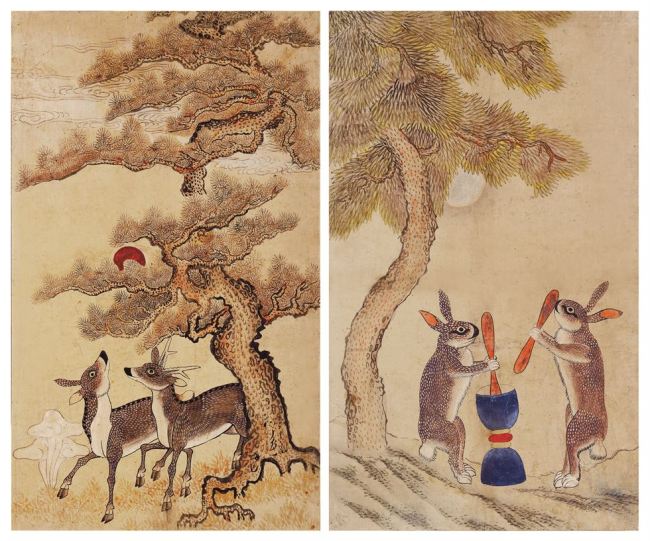

Both present-day Koreans and non-Koreans are likely to find Minhwa more than simply historically interesting. In fact, Minhwa can seem strangely familiar, even to an Englishman like me. This is because the dreams and hopes of the people of Joseon were not so very different from those of the English today, or from anyone else. They touch on the perennial desire for happiness and longevity. The style in which these universal aspirations are visualized is also highly accessible to non-Koreans on a purely aesthetic level. The simple outlines, flat patterning, bold colours, stylization to the point of caricature, and subject matter drawn from nature and everyday life, make Minhwa an art that connects to a quasi-universal language of visual and stylistic preferences. Consequently, while the specific cultural context with which Minhwa was produced has completely disappeared, and although today people in the developed world are no longer consciously attached to an animistic worldview, the pictorial values of Minhwa allow us to perceive not only unsurmountable cultural differences but also a common share of cultural similarities.

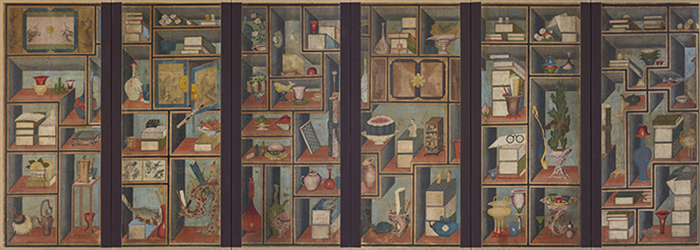

Minhwa has been categorized as ‘decorative art’, that is, as purely aesthetic in the narrow sense of being visually pleasing and functional. But to describe Minhwa as ‘decorative art,’ is misleading, because for those who owned such works, they were not only beautiful but also useful because they were understood to be imbued with magical power.

Minhwa has also been likened to the expressionistic paintings of modern artists like Picasso. Both comparisons are misleading. Minhwa cannot be described as ‘decorative’ in the Western sense because it is also symbolic, and functioned as part of the culture’s ritual processes. But nor can it be described as ‘expressionistic’ in the sense that modern Western painting is ‘expressionistic.’ Modern Western artists were often directly inspired by ‘primitive’ art, although Korean Minhwa was largely unknown in the West in the early twentieth century, and certainly did not have the impact of Japanese prints and African tribal art. However, the qualities that attracted Western artists to non-Western art are clearly evident in Minhwa. What Western artists were seeking in non-Western models was alternative traditions to the one that dominated their culture, which derived from the Renaissance, and put a premium on the rational analysis of form, and the representational illusion of three dimensions as on a two-dimensional surface using perspective. Examples of non-Western art were appropriated as primarily aesthetically atypical phenomena with the capacity to subvert the norm, and their utility and symbolic function were ignored. For the avant-garde, ‘self-expression,’ ‘authenticity,’ ‘aesthetic autonomy,’ and ‘expressiveness’ were the most important artistic qualities, and were linked to the capacity to innovate according to inner necessity. As a result, emphasis was placed on the individualism of the style of the artist. Minhwa, by contrast, is made by anonymous artists who followed specific pre-determined rules mandated by the requirements of their clientele, and they were committed to the expression of a clearly defined consensual worldview.

The power of Minhwa lies ultimately in the fact that it participates in a universal code — a common denominator for all living human beings, a core of desires and beliefs that is tied to basic human activities like eating, defecating, procreating, sleeping, and aging.

The power of Minhwa lies ultimately in the fact that it participates in a universal code — a common denominator for all living human beings, a core of desires and beliefs that is tied to basic human activities like eating, defecating, procreating, sleeping, and aging. Furthermore, despite the ‘disenchantment’ that has come with modernity, magical ways of thinking persist, and they connect us to a power that cannot be fully accounted for according to strictly rational criteria.

What makes Minhwa immediately accessible and appealing to both the modern Korean and the non-Korean eye is not its role within a code that must primarily be read like a text, and depends on study. Rather, we can respond directly to these painting’s extraordinary decorative and expressive force, which corresponds to experience as it occurs at the common human core more directly than words. Minhwa impacts at a pre-verbal level that is also trans-cultural.

About Simon Morley

I am British artist, writer, and former university lecturer. I live near the DMZ, the heavily fortified border between North and South Korea. This blog contains some of my reflections about and because I live in such a place.

I am the author of Modern Painting. A Concise History (published September 2023 by Thames & Hudson), By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose (Oneworld, 2021), The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art (Reaktion Books, 2020), and Writing on the Wall. Word and Image in Modern Art (Thames & Hudson, 2001). I am also editor of The Sublime. Documents in Modern Art (Whitechapel Art Gallery/MIT Press, 2010).

My artworks, mostly paintings, have been exhibited internationally.

See more of Morley’s work at Notes From The Edge, where this article first appeared.