By Chimezie Chika

Samuel Oladele, a young photographer from Nigeria, now based in Manchester, United Kingdom, seems to have found, in his photography, a place where his images can intriguingly straddle two or more meanings. Oladele portraits seem to give us one thing on one end of their frames, and other things at other ends of their frames. When we view the pictures, we are drawn into a region of borders, boundaries, and limits. When asked about this idea behind his photography, Oladele calls it the unique African way of looking.

But what do we see in the artist’s oeuvre, curated as they are? In the Instagram page dedicated to his art photography alone (he does a lot of work in commercial photography but considers it distinct from his other photography), we find photos of pensive faces, photos with spiritual overtones, photos capturing figures in normative poses, or photos that manipulate light and those in which the photographer makes bold—even less than satisfactory—moves with editing.

When he looked at the cars, what he saw first was not a status symbol, as cars are seen in Nigeria, he saw the chassis conditions of the cars and the stories, told and untold, that they held.

For Oladele, photography has been a life-long preoccupation, a mark of his interest in the little events that define daily living. There’s a sense in which his photography draws unrelenting inspiration from his own life. This quality is not unique to him alone, however; it is something that is ever more evidenced among artists: personality and interest as the impetus for artistic creation. While he was involved in real estate and the marketing of used cars back in Nigeria, Oladele not only saw it as a means for financial gain, it was clear to him that he was interested in the “miles’ of cars as something that has been pre-owned by some other people somewhere else in the world, or the lands as something owned and full of stories. When he looked at the cars, what he saw first was not a status symbol, as cars are seen in Nigeria, he saw the chassis conditions of the cars and the stories, told and untold, that they held. But he says that while business taught him valuable skills, “it did not ignite his soul”.

Upon discovering photography in 2020, during the Covid-19 lockdown, it seemed to him that he had found a potent form of self-expression. What began as a hobby, became a serious enterprise when he apprenticed himself to a photographer in his native Ilorin in 2022. In that time, he became drawn to what calls “life’s beauty and complexity.” If beauty and complexity are Oladele’s crucial compass for navigating his art, then we can point to a few things with certainty in some of the works he has exhibited in galleries in Europe, Asia and North America. A few of those works would suffice here.

Enacting African Spirituality

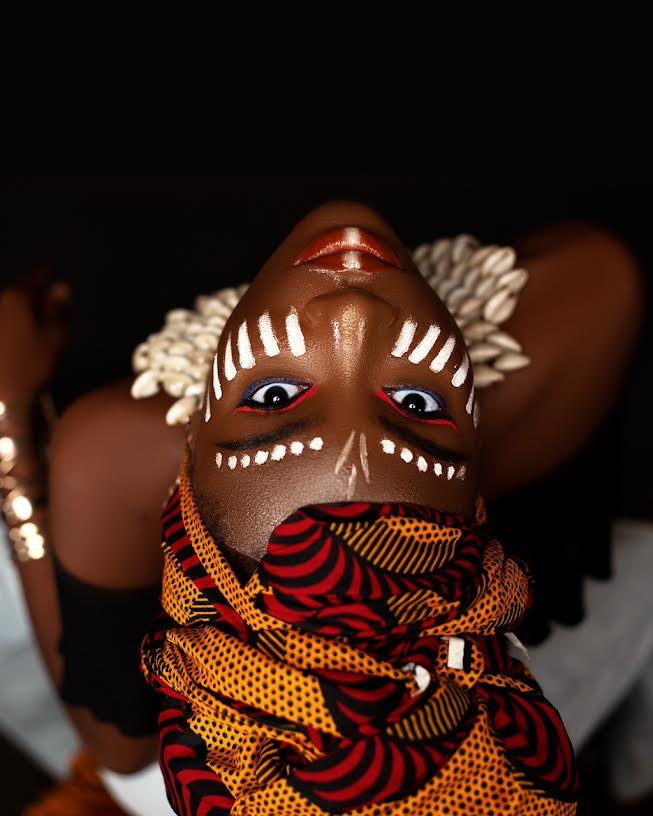

A kind of deliberate blurring of certainty seems to define what Oladele does in his photography. The composition of his pictures seems to start from one point and end in several others. This way of looking at things defines the tenuously liminal world of African spirituality around which some of his images are themed. In the dual photo titled, “The Chad Wodaabe’s Culture”, a young woman looks boldly into the camera. Her face is contoured in what is more or less the white face markings of a female sangoma or priestess in Southern Africa. What draws us in irretrievably is endless pools of depth in her straight-gazing eyes. Another image, quite ordinarily titled “Youth and Freedom”, orchestrates a more daring image of African spirituality. Here, the subject has been so altered by face makeup it is now positively hard to call her a human; her face is dark with dashes of aquamarine blue and gold on her forehead, cheeks, and jaw. Her sidelong gaze is also dominated by unearthly blue pupils. Could the photographer’s intent be venerating the pantheon of African goddesses? Other poses seem to confirm this. In one, the posture of her hands seems to denote that of a conjurer; in another her hanging tongue can only mean the invocation and sacrifice.

In “Golden Empress”, a young woman’s further blackened face and gold-ladened eye shadows and lips continues to stretch Oladele’s narrative of African spirituality. The idea behind this tripartite photo celebrating enigma, beauty and the supernatural seems to come directly from the practices of the photographer’s own tribe, the Yoruba, especially the rich culture around Isese Festival in Ilorin and the rest of Yorubaland.

There are photos in which Oladele seems to incorporate other spiritual traditions from around the world. The idea behind “Inferno’s Dance” emerges from East European and far Eastern traditions of fire-mongering. Here, a white woman in underwear plays dexterously with fire in a darkened room; there is little else to see except her face, the sensual contours of her body, and the blazing fire she wields like a second skin. In one photo she holds the fire directly in her hands while gazing into the camera; in another, she puts some of the fire in her mouth with her head tilted upwards; in the last photo, her figure has been completely swallowed by the darkness of the room and we can only vaguely identify her two hands holding sticks of the fire in an aggressive pose, and the fire which now seems to blaze freely in the near darkness, appears to have acquired the aura of something beyond the substance of the material world.

Ideated Figures

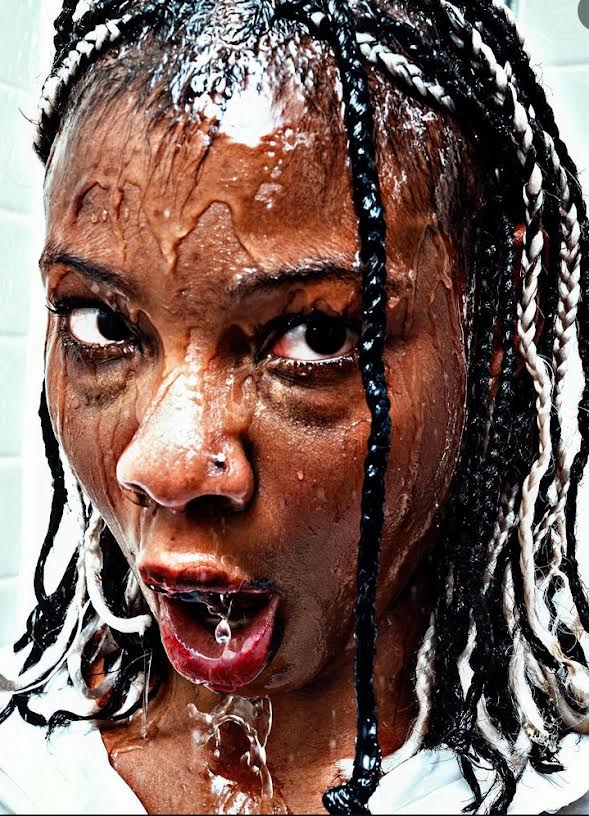

One of the photographs, “Reflections”, is the image of the blurred figure of a young woman in a singlet, biting down on a finger of her right hand in a pose that seems to showcase swagger. There is nothing more to see except her background, which seems to be a restroom. And here, we know that restrooms can be therapeutic and relieving in times of great stress; one can play one’s emotions in privacy. One thing that jumps out here is the photographer’s grunge aesthetics. Same thing can be found in “The Water’s Edge” which does not show the edge of water at all. What we see here is the portrait of a young woman on the other side of what appears to be a screen of glass which has become dappled with droplets of rain water. The image has been hyper-edited and fails to convey authenticity. But, here again, the figure denotes deep thought and introspection.

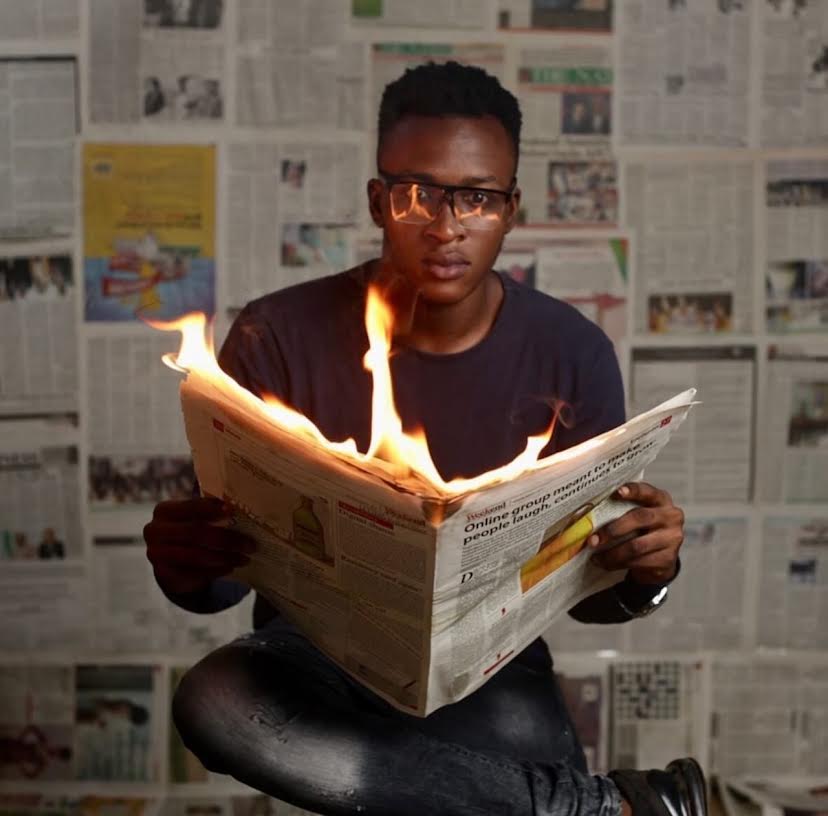

More or less, these are signs of images based on ideas and projection. There is deliberation in the method of their composition. We find, especially, that photography uses props to achieve the desired effect based on the ideas he wants to create. In “Flame in the Trees”, for example, a young man is captured reading a burning newspaper though his gaze is facing the camera directly. The photo seems to be both a commentary on the cracking down on press freedom in various countries in Africa presently as well as voicing concerns about ecological sustainability of the paper-making industry which depends on the depletion of forest around the world.

But Oladele is quite capable of taking introspection to even more suggestive levels, where light and darkness is applied to show mood meaning. “It’s One Sided”, the best photo in this series, has that attribute in which the images seem to exist in the middle of their own references. Here, the borders where the photos exist are their material consequence.

Chimezie Chika is a writer of fiction and nonfiction. His works have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Shallow Tales Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Lolwe, Iskanchi Mag, Isele Magazine, Efiko Magazine, and Afrocritik. He was a 2021 Fellow of the Ebedi International Writers’ Residency in Iseyin, Nigeria. He is the Fiction Editor of Ngiga Review and currently resides in Nigeria. Find him on Twitter @chimeziechika1.

Categories: featured, Photo Essay, photography