By Arthur Davis

Spring, 1681-2

Cherry Blossoms in Edo

Basho, age 37-38

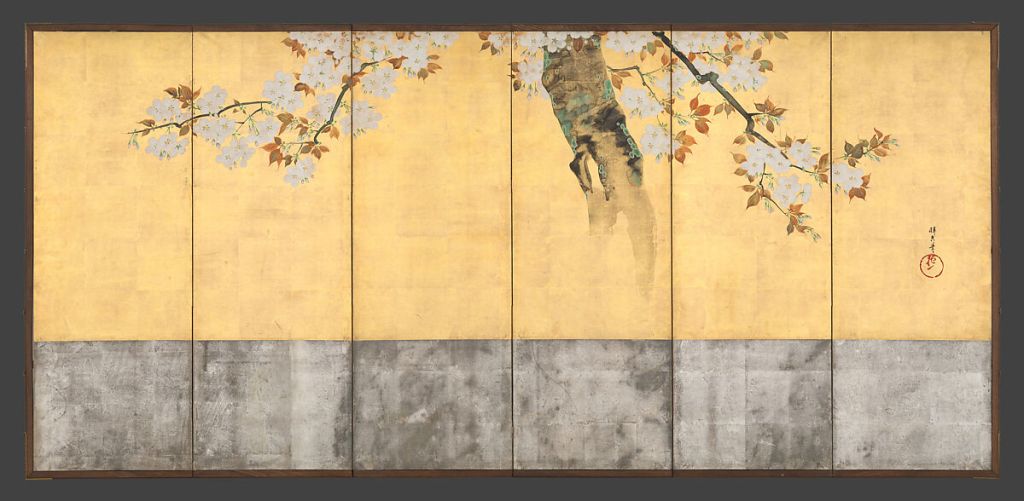

Drunk on blossoms

a woman in a haori,

pointing with a sword花に酔えり 羽織着て刀 さす女

Hana ni yoeri haori kite katana sasu onna

Hana ni ee ri haori kite katana sasu onnaMatsuo Basho, Edo, 1681-2

Translation. Hana (flower, here meaning a cherry blossom) ni (particle to indicate cause) yoeri (to become drunk) haori (a short jacket, women wear over a kimono) kite(wearing) katana (sword) sasu (pointing, stabbing) onna (woman)

Cross-Dressing

Japan was unified under the Tokugawa clan. War was over. Peace was at hand. In Spring, the population turned its attention to viewing cherry blossoms and getting sloshed on sake. What one wore was a sign of a person’s status and family background. The haori, a lightweight jacket, became casual wear for samurai warriors and popular attire for up-and-coming townspeople. Women adopted the style along with the men as it could be worn over a kimono.

But a woman carrying a sword would be quite the sight.

Onna-Bugeisha, literally, “female who practices the Art of War.” The 3rd century Empress Jingū, was one of the earliest female warriors. It is likely that Matsuo Basho was familiar with the Tale of Heike which recounts the story of Tomoe Gozen, a female samurai who fought for the Minamoto clan. Basho wrote a haiku about the Genpei War between the Minamoto and the Taira clans.

Gabi Greve and the Japanese site Yamanashi date this haiku to when he was 38 to 40, first to third year of Tenwa, 1681 – 1683. A year before, Matsuo had moved from central Edo to the rural Fukagawa District to take up residence in a simple cottage. A house warming gift of a banana plant (basho) was planted by the front door, and Matsuo had the idea of a new name.

June 29, 1689

After dreamy Matsushima, Matsuo Basho and Sora are off to Hiyoriyama, home to the lost glory of the Fujiwara clan.

But before that it is Ishinomaki. By some accounts, station 22 on the Oku no Hosomichi, Matsuo Basho’s best-known travelogue, in English, The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

Journalists and historians write what they remember, poets dream.

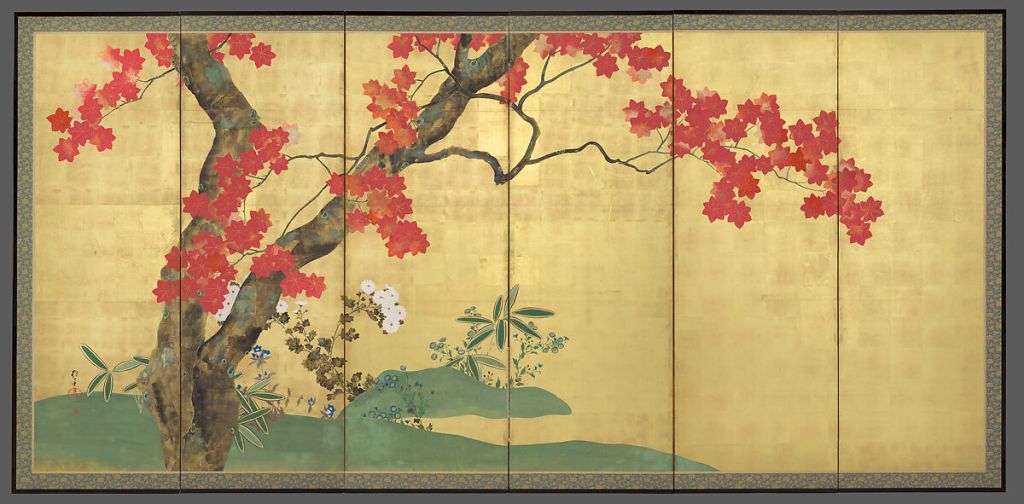

Basho recalls that he and Sora had taken a path used only by woodcutters and hunters and had gotten lost on their way to Hiraizumi. The path was difficult and somehow they got lost. Then on a hilltop at Hiyoriyama, in the midst of colorfully blooming azaleas, they were able to see a bird’s eye view of the port city of Ishinomaki.

Sora says in his journal that they were never lost.

Basho says it was the 12th day (十二日) of the fifth lunar month, June 29 by today’s reckoning.

From Oku No Hosomichi:

石の巻

十二日、平和泉と心ざし、あねはの松緒だえの橋など聞傳て、人跡稀に雉兎蒭ぜうの往かふ道、そこともわかず、終に路ふみたがえて石の巻といふ湊に出。こがね花咲とよみて奉たる金花山海上に見わたし、数百の廻船入江につどひ、人家地をあらそひて、竃の煙立つゞけたり。思ひがけず斯る所にも来れる哉と、宿からんとすれど、更に宿かす人なし。漸まどしき小家に一夜をあかして、明れば又しらぬ道まよひ行。袖のわたり尾ぶちの牧まのゝ萱はらなどよそめにみて、遥なる堤を行。心細き長沼にそふて、戸伊摩と云所に一宿して、平泉に到る。其間廿余里ほどゝおぼゆ。

Ishinomaki

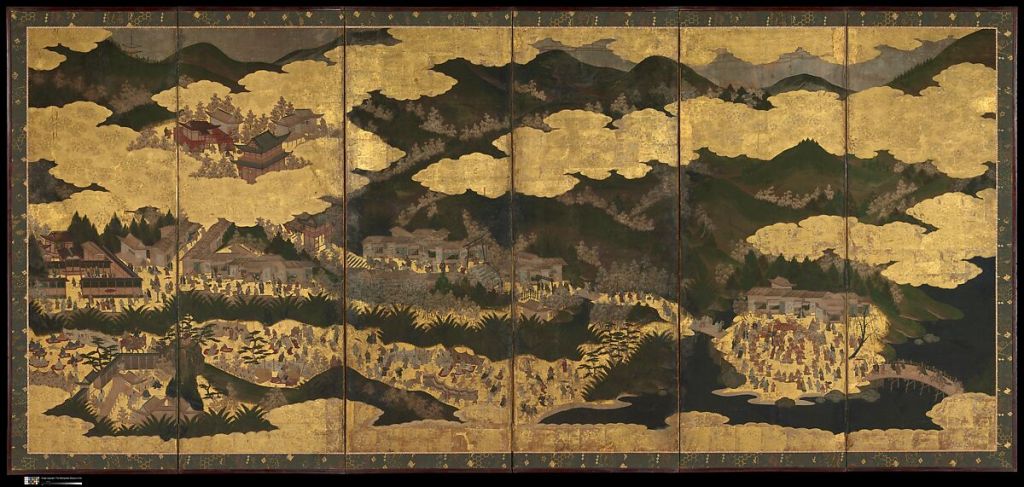

From the hilltop at Hiyoriyama, Basho saw “hundreds of ships, large and small, entering the harbor, and the smoke rising from countless homes that thronged the shore.”

Chance brought him to this village. Tired from his arduous trip, longing for a comfortable place to stay, but no one offered him any hospitality. A search produced a miserable house and an uneasy night.

Hoping never to see Ishinomaki again, Basho and Sora set off the next morning on a difficult two day journey to their destination, the small village of Hiraizumi.

Hiraizumi, 平和泉, its very name means the village of Peace and Harmony, a place of gardens and Buddhist temples centered on the idea of Peace in a Perfect World. That it was not easy to find, would call to mind the following story.

Peach Blossom Spring

Peach Blossom Spring, Tao Yuanming (陶淵明), written in 421.

It is the story of a chance discovery of an imaginary place where, for centuries, villagers have lived in harmony, unaware of the outside world. In Tao Yuanming’s story, a fisherman sails on a stream in a forest of blossoming peach trees, where even the ground is covered by peach petals. At the source of the stream is a grotto. Though narrow, he can squeeze through and this passage leads to an undiscovered village.

The villagers are surprised to see an outsider, but they are friendly and kind. They set out wine and chicken for a feast and explain that their ancestors came here to escape the war and unrest during the troubles in the age of Ch’in (2nd c. BC), living in peace ever since. The fisherman stays for a week.

Leaving, he marks his route, but can never discover the village again.

The 21st Century Wanderer

Who has not dreamed of a place somewhere over the rainbow where blue birds sing, of a Brigadoon or Shangri-la, a lost Atlantis? Reality, sadly, often shows us life can be, a frightening Brave New World. And if not frightening, then mundane, until we are once again surprised.

Utopias are the dreams of novelists, philosophers and poets. And it is okay to dream.

Prospero:

Our revels now are ended.

These our actors, As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air: And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d tow’rs, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.

We are such stuff As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.William Shakespeare, The Tempest Act 4, scene 1, 148–158

Quoting Matsuo Basho in his Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi, 奥の細道).

Station 2 – Departure

Early on the morning of March the twenty-seventh I took to the road. Darkness lingered in the sky. The moon was still visible, though gradually thinning away. Mount Fuji’s faint shadow and the cherry blossoms of Ueno and Yanaka bid me a last farewell. My friends had gathered the night before, coming with me on the boat to keep me company for the first few miles. When we got off the boat at Senju, however, the thought of a journey of three thousand miles suddenly seized my heart, and neither the houses of the town nor the faces of my friends could be seen except as a tearful vision in my eyes.

Spring is passing!

Birds are singing, fish weeping

With tearful eyes.With this verse to commemorate my departure, I began my journey, but lingering thoughts made my steps heavy. Watching friends standing side by side, waving good-bye as long as they could see my back.

Yuku haruya

Spring is passing! Yuku haruya!

The wonderful thing about poetry in verse is that one can read and reread the same poem or the same verse. It is, in a sense a new beginning. It is a chance to start over, although it is on a familiar path, and even so, change directions. Maybe it is a journey into a better lifestyle, with daily exercise and healthier eating.

That new beginning always starts today.

Spring, in verse, in poem,

Perpetually Passing

And yet, it begins anew

Bashō no yōna

Senju

Basho began his journey in the late spring of 1689. His wanderlust lasting over five months — 156 days and nights, to be precise.

The first leg of the journey was by boat from the Fukagawa District where Basho was then living, along the Sumida River, to Senju, today’s Adachi fish market, in the northern part of Edo (Tokyo). From there it was a short walk to the Arakawa River and the bridge that lead north.

Surrounded by the fish mongers and the birds dancing around looking for scraps to eat, Basho began his journey with tearful eyes. He was not quite alone, for Kawai Sora, his neighbor in Fukagawa, would be his companion.

Original Japanese

行く春や

鳥啼き魚の

目は泪

Yuku haruya

tori naki uo no me

wa namida

Matsuo Basho reveals to his disciple Kyori that he and his neighbor Kawai Sora are planning a trip. The trip that would make Basho famous.

How wonderful!

This year, this Spring

As I journey under the sky (Sora)

I おもしろや ことしの春も 旅のそら

omoshiro ya / kotoshi no Itam mo / tabi no soraMatsuo Basho, Spring 1689

According to a disciple of Basho, Mukai Kyori (向井 去来, 1651–1704), this haiku was written as a way of saying he was going on a trip with his neighbor Sora, whose name means “sky.” After Basho’s death in 1694, Kyori published stories about his master.

The trip was to become Oku no Hosomichi, a nine-month journey into Japan’s Northern Interior. The notes and haiku Basho wrote along the way would not be published until eight years after Basho’ death in 1694. It would in time make his name immortal.

Read more of Arthur Davis’ thoughts on Matsuo Basho’s poetry here.

Categories: featured, literature, poetry

This is a treasure trove of information and beautiful poetry! I loved reading through this and the many connections that are made through time!

LikeLike