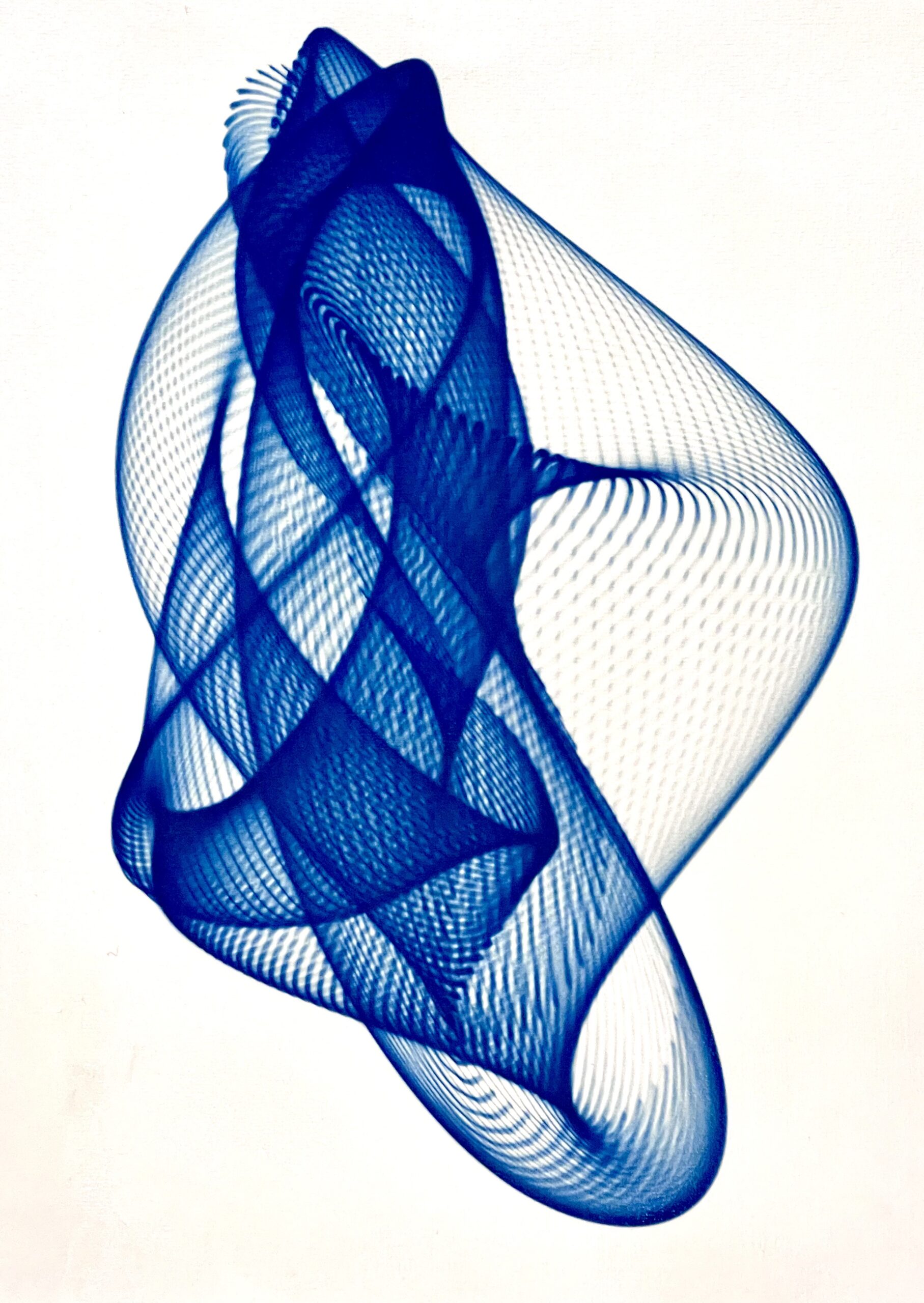

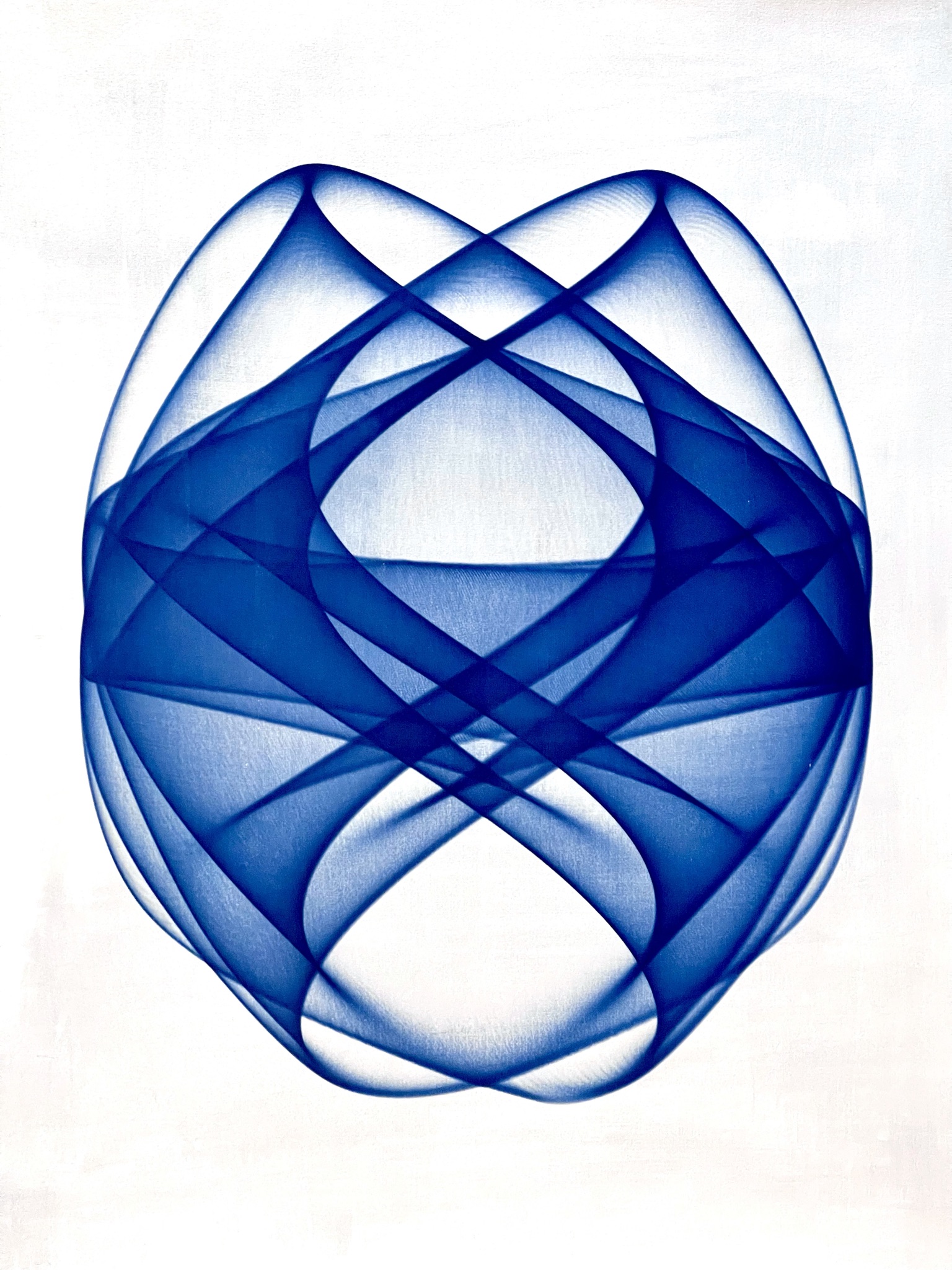

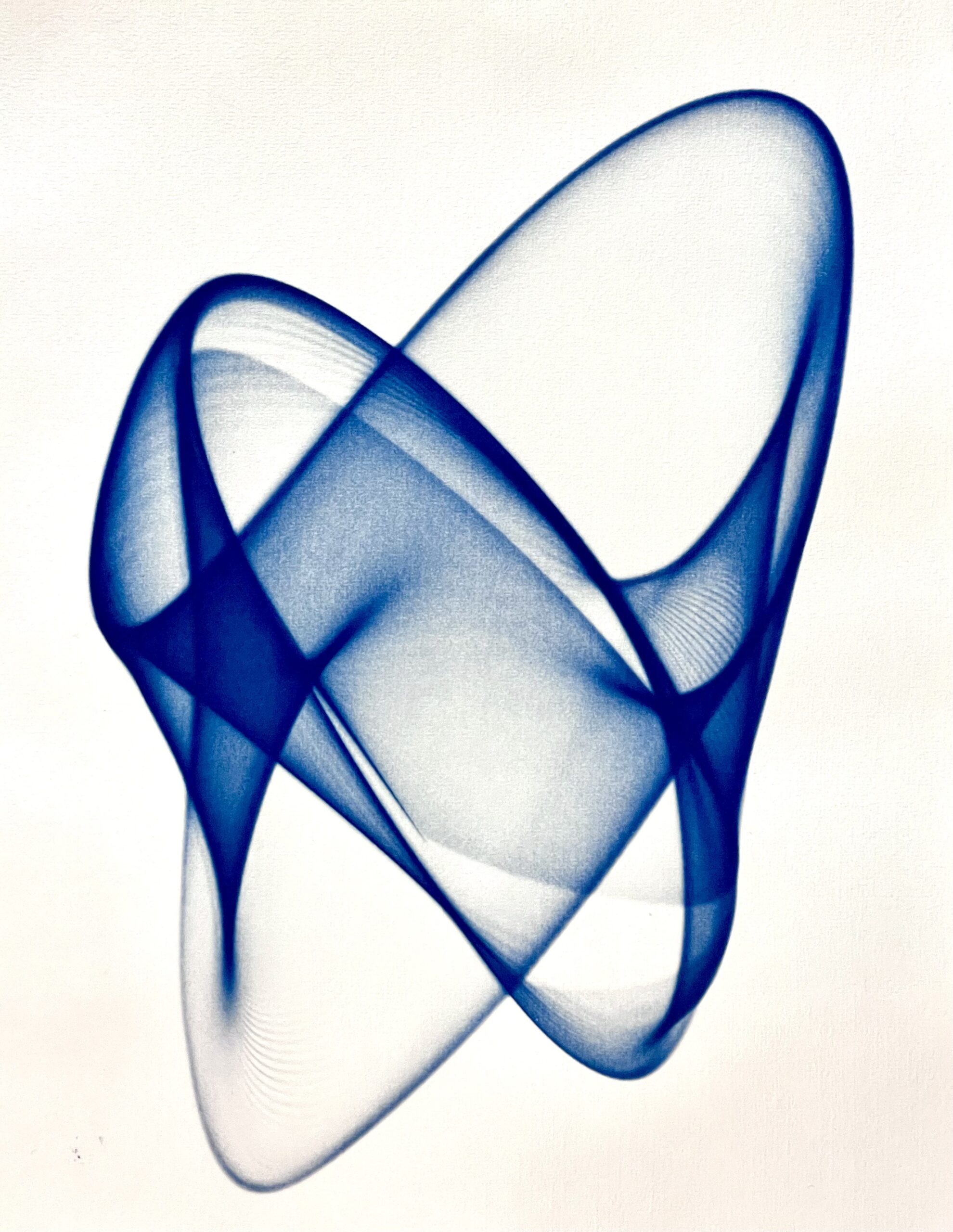

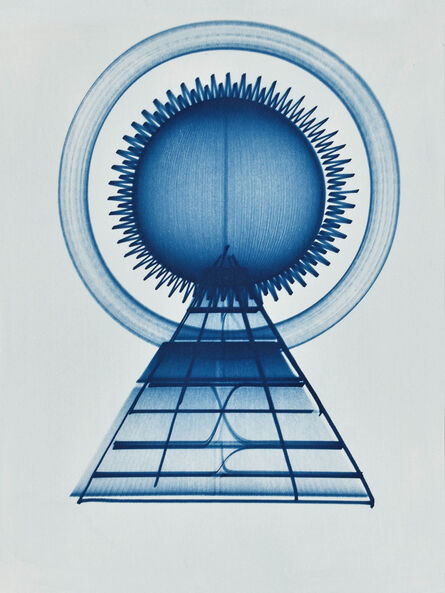

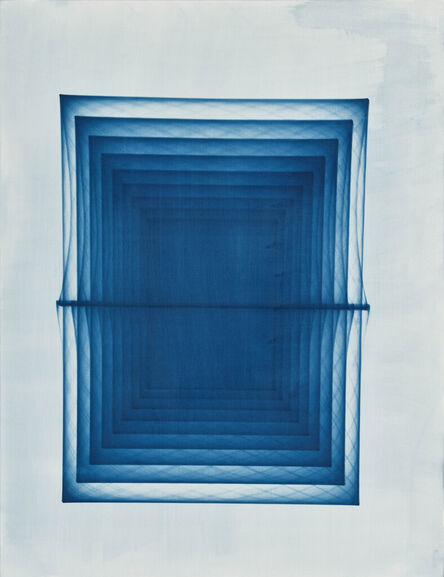

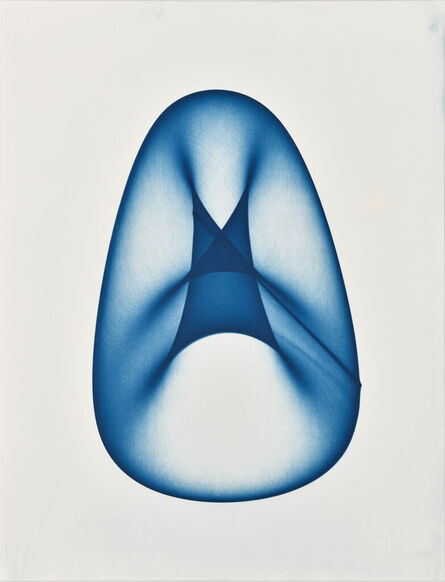

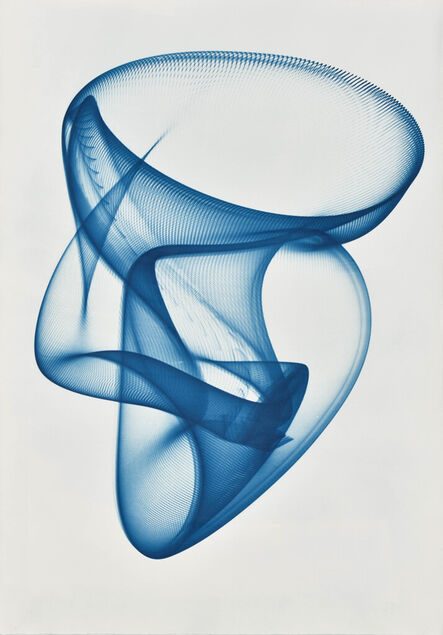

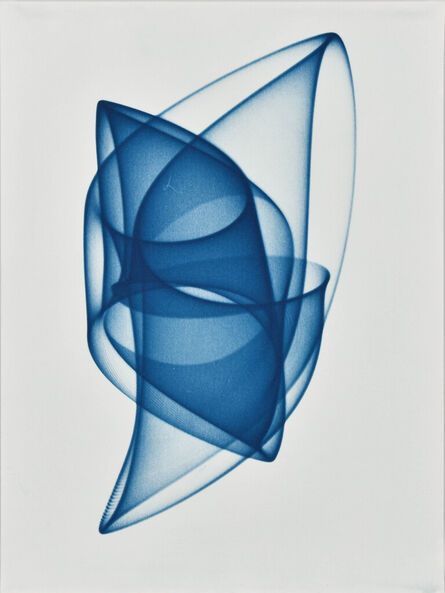

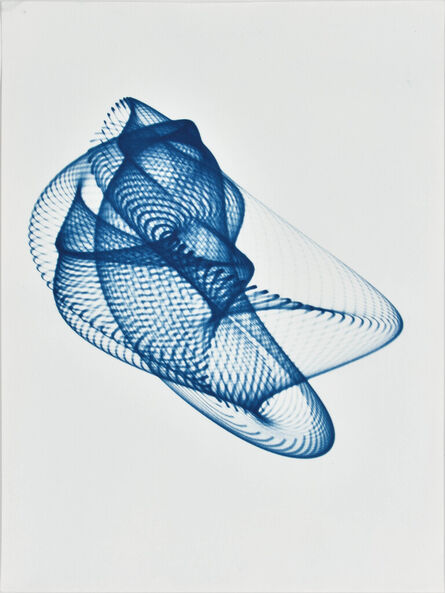

Ralf Jacobs’ Laser Cyanotype Harmonograms and Light Flukes straddle the worlds of art and technology. They’re an intriguing combination of science, photography, drawing, and painting. He ‘writes with light’ in a wonderful spectrum of old and new techniques, from 19th-century cyanotypes to software-guided laser projections. He combines different photographic procedures and images to create new realities that incorporate time as a tangible presence.

“People at work think I’m special cause I do art, people in art think I’m special cause I do technology, I’m right at the intersection. A lot of people in art are afraid of technology or think they can’t understand it. And people in technology wonder why would you do art, they ask why would you do something cause it’s pretty when we have enough pretty things in the world already. I like being the mediator between two worlds, it gives me a purpose.”

His background is in physics and technology in Optics. “I work at a firm that designs and builds high-tech machinery. In these machines things need to be measured: positions and displacement, temperatures, forces, pressures, and products need to be inspected. I design optical equipment (microscopes) and sensors as parts of these machines. I’m around a lot of fancy technological equipment and analysis tools all day, and it inspired me to find a bridge between my day job and what inspires me in art. These drawings I make are very much related to the field of physics and mathematics, but you don’t need to have an understanding of mathematics to say a drawing is attractive or not. The beauty is transcendental.”

Jacobs finds his job fascinating, but it’s frustrating to him that he can’t talk about it, or describe the way the process works. Sadly, he can’t ever tell “… the juicy details (if ever they are juicy) … I work for commercial companies that build machinery and processes to make products they can sell. For example, these machines enable the production of microchips and displays. All my work is done under NDA, in secrecy from the outside world, and eventually patented. I love to tell stories about what we create, but I can’t go into detail. This was a bit of a frustration, as I cannot explain the wonder I experience when working on something technological. My art practice is centered around showing the world that wonder. I can talk about my blue drawings and how they came to be and the techniques behind them for hours.”

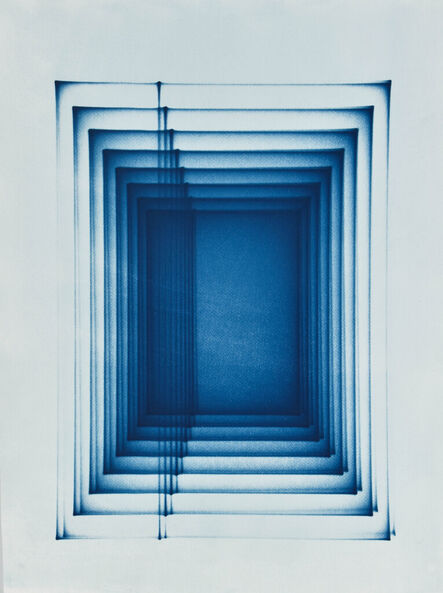

In Jacobs’ art there’s a sort of circle of discovery from the beginning of photography to the present and looking towards the future. The cyanotype process is as old as photography itself, but Jacobs realized he could apply his professional knowledge to the field. The process provides a welcome outlet from the rigors of his job. “I started with art ten years ago because I work in an office most of the time, or a laboratory. The job is fun but it’s still a job. Lots of meetings and emails. I started working with cyanotypes when I had to work at home a lot due to Covid-19, sitting at home instead of in my lab at work was a lot less inspiring, and I was looking for a practice that would enable me to make photographic art at home, and I started making these blue drawings.” He discovered the laser and cyanotype process and just started working with it. Cyanotypes take time, sometimes an hour to irradiate, and this worked out well with his new schedule of working from home during quarantine. “So I can just start one before I go into a meeting and make them while working. It’s not a very fast process; it takes an hour of waiting, usually, and for big images even longer, but that gives quite a nice pace to it. It’s a very relaxed process and that’s what I enjoy very much.”

He did experiment with other photographic processes, but it turned out that cyanotype was best-suited to his art. Cyanotype is one of the most accessible and forgivable photographic processes. You don’t need total darkness and it doesn’t require toxic chemicals. “Yes, I tried a few things. First I tried normal darkroom photography but my laser is very powerful and the photographic stuff is 1000 times more sensitive than cyanotypes, so I needed to illuminate for parts of a second, which was difficult technically. But the cyanotype is much slower, so I can do it in my kitchen, without poisoning myself, without total darkness. In practice, it’s a very nice process that you can do anywhere.” He’s even used the process in public, at festivals; he just brings his laser, which is roughly the size of a watermelon.

“I have photographic cyanotypes as well, but when I talk about harmonographs or harmonograms I talk about drawing, which is drawing with light.”

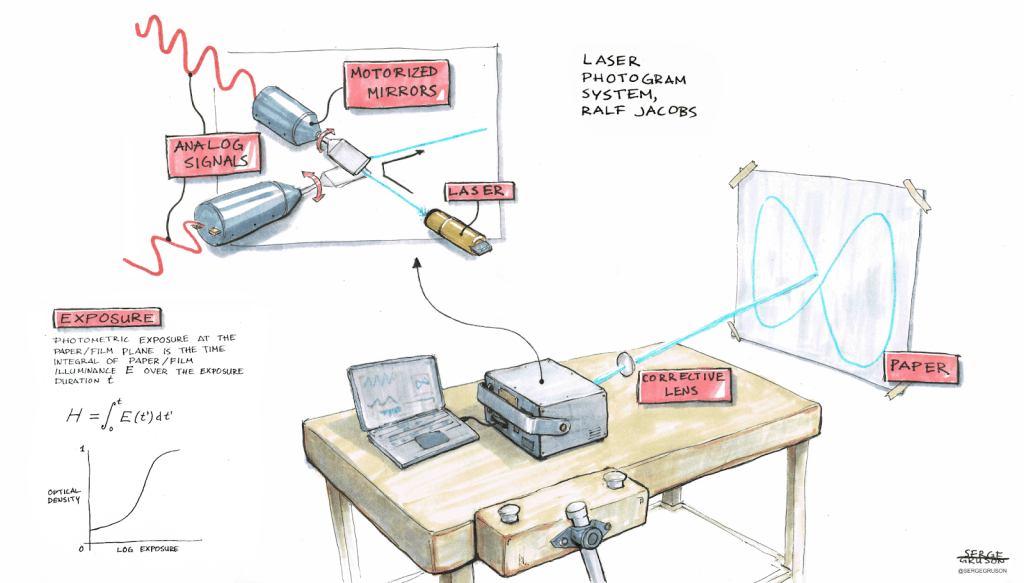

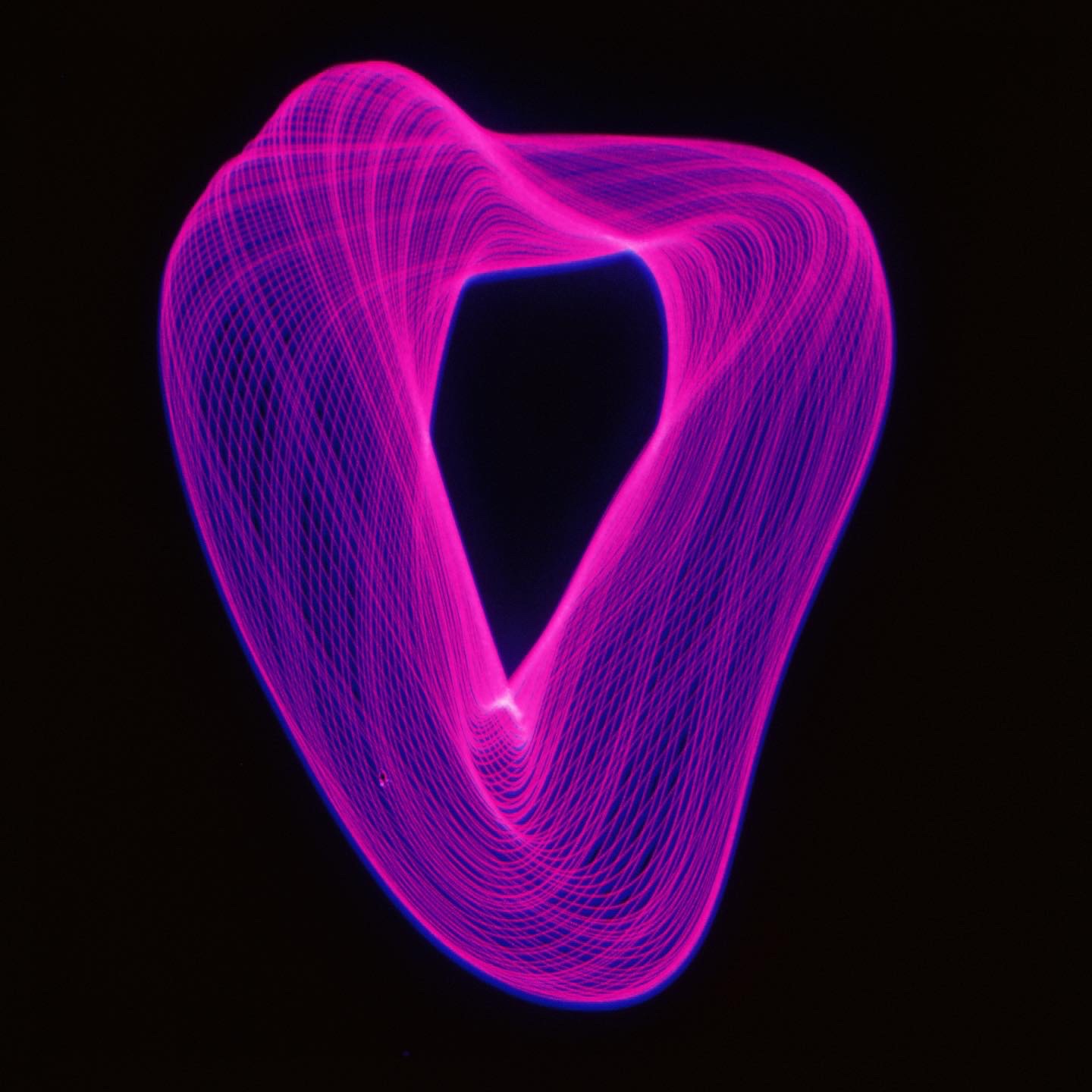

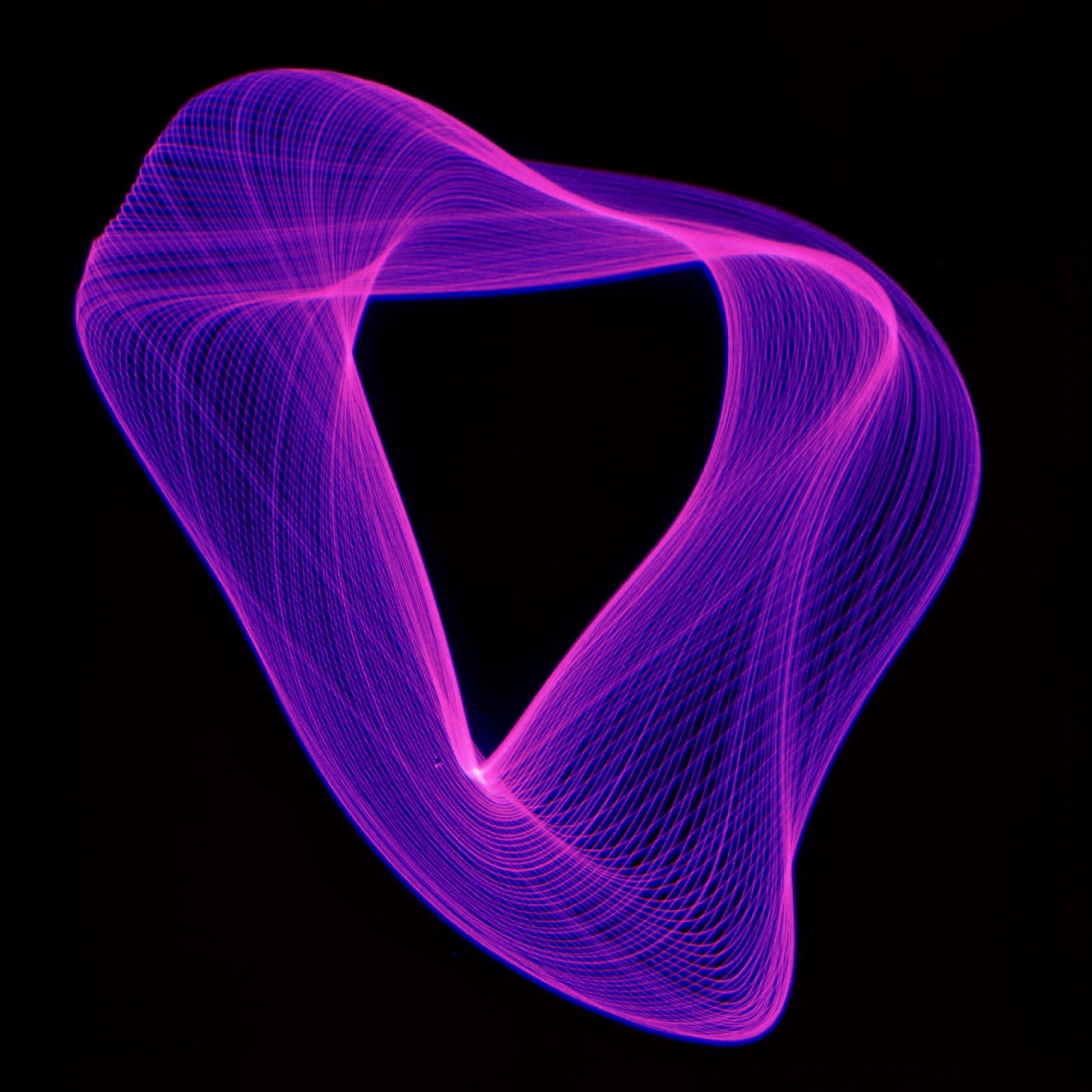

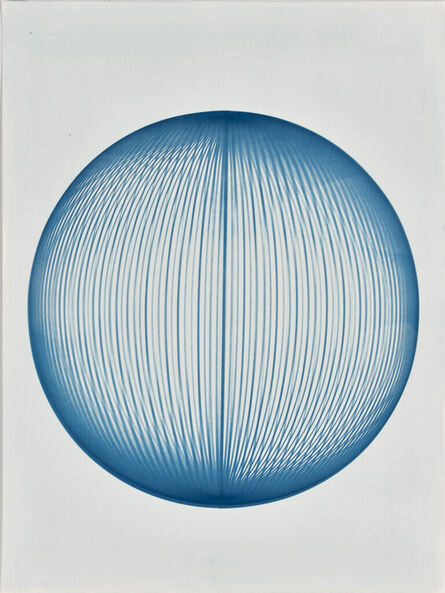

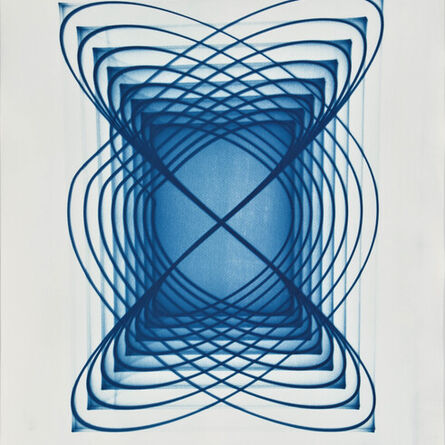

Jacobs calls his artwork drawings rather than photographs, and explains, “It’s a photographic process, but it’s really a line, and when you follow the line that’s how the drawing appears on paper. I have photographic cyanotypes as well, but when I talk about harmonographs or harmonograms I talk about drawing, which is drawing with light.” He explains that “It’s it computer running the program. I program shapes with a lot of parameters, and create interlinks between parameters. It sounds hokey pokey, with lots of knobs to turn and connections to make between knobs. But I don’t type code to set things, I look to the parameters, and the simulator shows about what the drawing will look like. But not exactly.”

Printing the images is a photographic process. “I smear the paper with some cyanotype solution. Two chemicals are combined, which gives a greenish kind of water. I smear this on paper, and the paper turns green. Then I position it in front of the laser. I program a pattern, and let it irradiate the cyanotype paper for about an hour. During this time, the pattern repeats itself every 10 seconds or so, and while irradiating I slowly can see the drawing appear. I have some idea how the drawing will turn out shape-wise, but the intricate details and gradients the laser draws I can only see when I start drawing. After the exposure time I develop the cyanotype in water. The green/yellow hue washes away, and the blue drawing appears where the laser has hit the paper.” There’s no need to use special photographic paper, and Jacobs uses watercolor paper. The chemicals are light-sensitive, and you can apply them to any paper or other surface. Jacobs has done some tests with clothing, textiles, and ceramic tiles. Jacobs observes that because of the adaptability of the cyanotype process, “…a whole community of people is doing cyanotypes. It’s really inspiring to see thousands of people in the world doing different things with this technique. It’s nice to observe how broadly you can utilize it.”

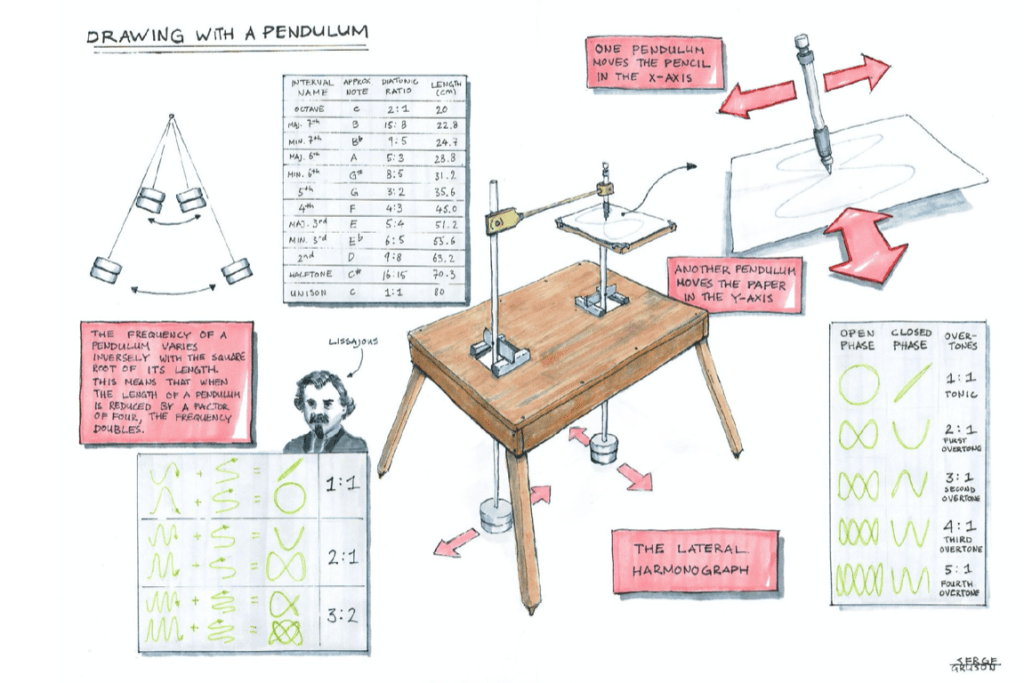

Jacobs’ process draws inspiration from an old-fashioned harmonograph, a machine with rods and weights that mechanically move a pencil across a piece of paper, and he uses software that creates digital versions to form and capture patterns. “The old-fashioned harmonograph with pendula, an invention from around 1850, and my modern laser scanner system with two rotating mirrors use the same principle, rotation, to draw. Therefore they create the same drawings fundamentally. These drawings are called Lissajous, after a French guy first documented them around 1850. They are named after him. But he didn’t invent them, as they are deeply embedded in nature, he just discovered and documented them. And we make them beautiful. He also did research into sound waves, which are repeating oscillations that look a lot like the signal coming from a harmonograph or my laser. This relation to sound waves is something I find wonder in very much. That you can see and hear the same signal, with two separate cognitive inputs into your brain, and can think about their relation.”

The patterns Jacobs has captured in his cyanotypes, aside from being aesthetically pleasing, have something deeply elemental about them. It feels as though he’s solidified light or sound, or the patterns of flying birds. They have the fragile vulnerable strength of skeletons of humans and animals. It feels as though he’s captured something transient—time and space–or taken a picture of a ghost.

But he insists that it’s not a ghost. “I’ve been always quite interested in things that look like they are from another world. My favorite genre of movie is sci-fi. I like Star Trek and Star Wars. It’s about extra-terrestrial life forms, but the whole genre was thought up by humans, and we have never seen an alien. We use our imagination to think what an alien could look like, and then we call it ‘alien.’ What I try to show is that all these things that could look alien are essentially coming from our nature, and therefore not as alien as some people think they are. With some explanation, everyone can understand where they’re coming from … Why do I draw these shapes and not other shapes? That’s a very good question. I try to play the laser like it’s a musical instrument, so I just sit behind it and I play something and when I play it enough and I think it results in something, I let it make an image I let it run for an hour and see what comes out, and then I adjust some things and try again, and that’s how I create these drawings. Why do they look like this? I can have a very analytical explanation for it. It’s not a ghost. It is not a ghost. It’s something from math and physics that I can explain and people can understand. But when you look at it doesn’t matter if you know physics and math, you can think it’s pretty anyway.”

“We use our imagination to think what an alien could look like, and then we call it ‘alien.’ What I try to show is that all these things that could look alien are essentially coming from our nature, and therefore not as alien as some people think they are. With some explanation, everyone can understand where they’re coming from.”

There are patterns all around us that we recognize in Jacobs’ work. Similarly, with music, we respond to sound waves, we can’t see them but they affect our emotions. Looking at Jacobs’ drawings, it feels that he’s captured something no one else has: A new way of looking at something that we always see but don’t always notice. “For a person working in a very analytic world, I really have an affinity with working from intuition. I program my shapes by setting a lot of parameters and creating geometric links between parameters and oscillations. I choose to program my shapes like a musician plays an instrument, intuitively reacting to what I see coming from the projector, tuning and improving.”

And the process is one that Jacobs invented. “There are quite a few people who draw with mathematics, but most do it on a computer and output jpeg images. These can be pretty but they’re not as romantic. I like the analogness of the process: that you have a laser, you have one dot and it can move and make circles and shapes and patterns. I know about one other person drawing cyanotypes with a laser, but he uses a different laser movement system. He uses fractals, so his drawings look different, though they’re the same medium. But how many people draw in the world? A whole lot. And they all get different results. The link from laser to harmonograph to cyanotype, that is my invention. But I use things that have been invented a while ago.”

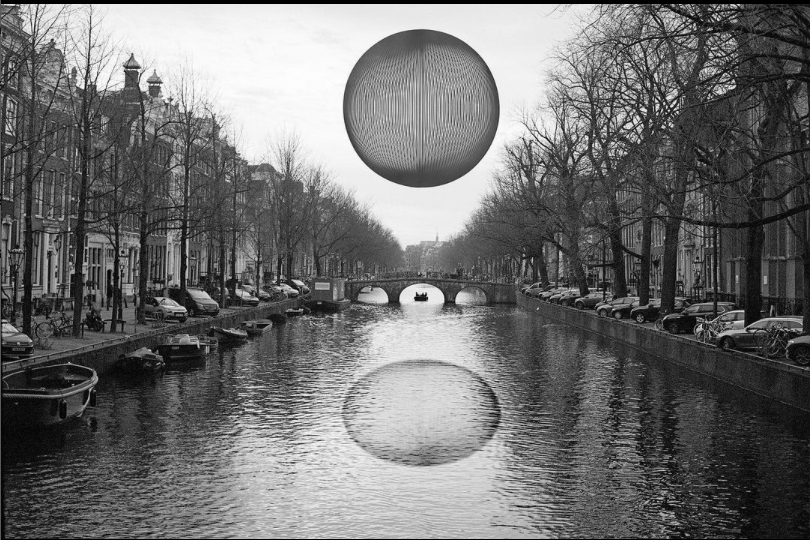

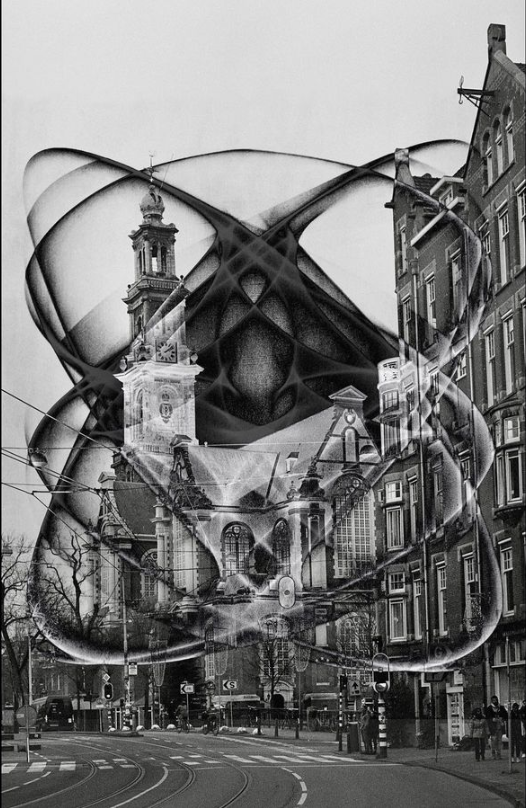

Jacobs describes the patterns as “alienating elements” and “reminders of all that goes on beyond our everyday perception of reality.” In addition to his drawings, Jacobs has a series of photographic cyanotypes of Amsterdam, and he’s added his patterns to the images. He takes pictures of places in Amsterdam that almost every tourist photographs, and incorporates some of the cyanotype patterns. This alters the photographic cyanotype in really beautiful, haunting ways, adding mystery and meaning. “It looks very alien, but I’m not alien, the process isn’t alien, some parts of it have been with us for hundreds of years. It’s not that scary, it’s not from a different world, it’s from our world, and we shouldn’t be afraid of it.” He’s made postcards and Christmas cards incorporating the otherworldly orbs.

“People ask me to play a song on it, but if I play a song, the drawing that comes out is like a big cloud. Because music, a long signal of music, is too chaotic to make a detailed drawing. It will just be a big cloud.”

Though Jacobs identifies a link to music in his drawings, he explains why it’s difficult to capture musical sounds precisely. “It’s interesting philosophically, harmonographs and harmonograms have certain rules, they work well in ratios. You’ve got two signals and the ratio between them is important. The funny thing is that in music the harmonic is the same; you can hear if the tone is the same as another tone. And you can see it if you draw with a harmonograph. People ask me to play a song on it, but if I play a song, the drawing that comes out is like a big cloud. Because music, a long signal of music, is too chaotic to make a detailed drawing. It will just be a big cloud. But when I limit the length and I go to individual tones and chords, I can create drawings that are a direct translation of sound to image. I can use the same sound to play on a speaker and you can hear it, and when I play the same signal in my laser and it will make a drawing. It’s kind of magical, but it’s very difficult to make a correlation between what you see and what you can hear. You can do it separately, but when you see something to know what it sounds like is almost impossible. But it’s interesting to dive into it.”

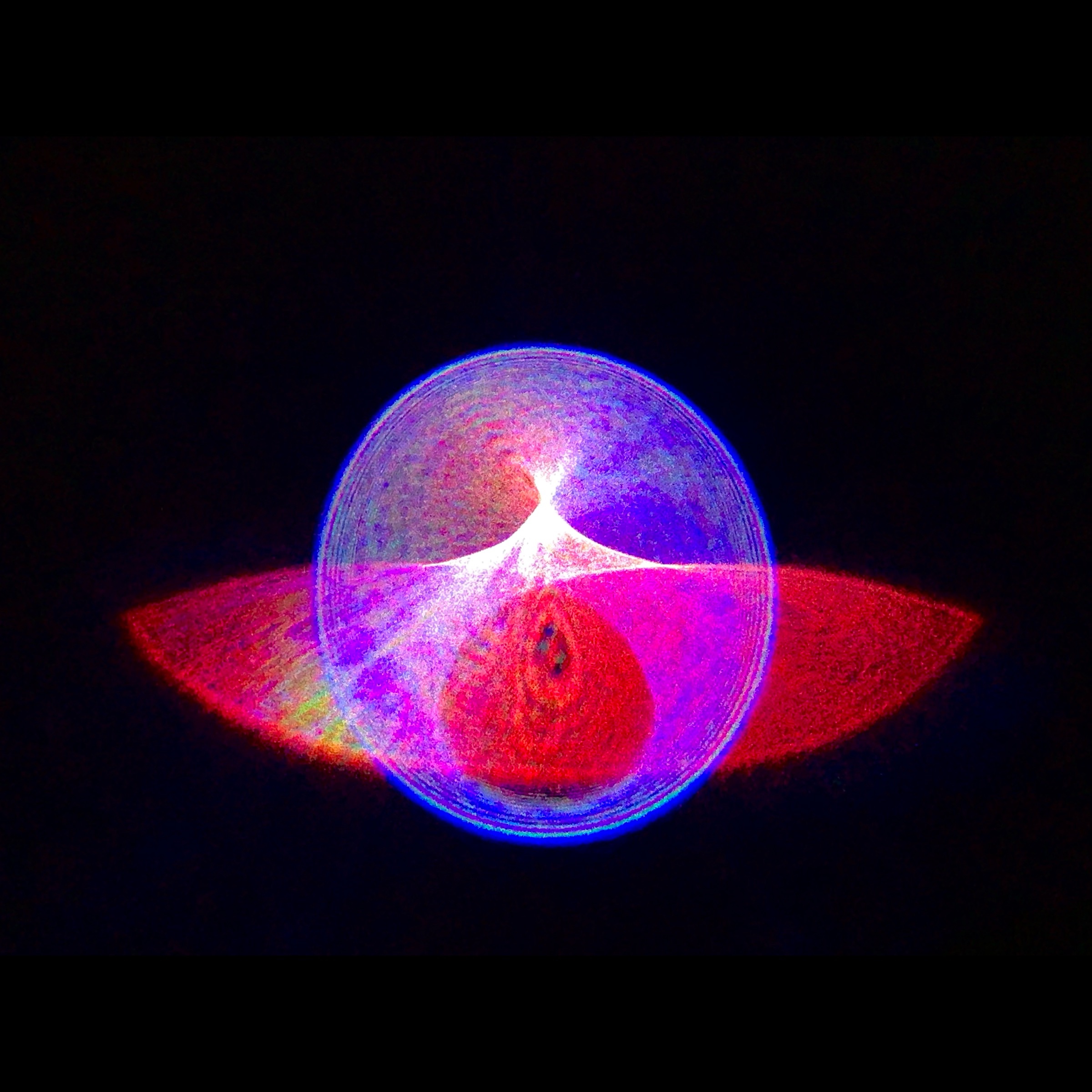

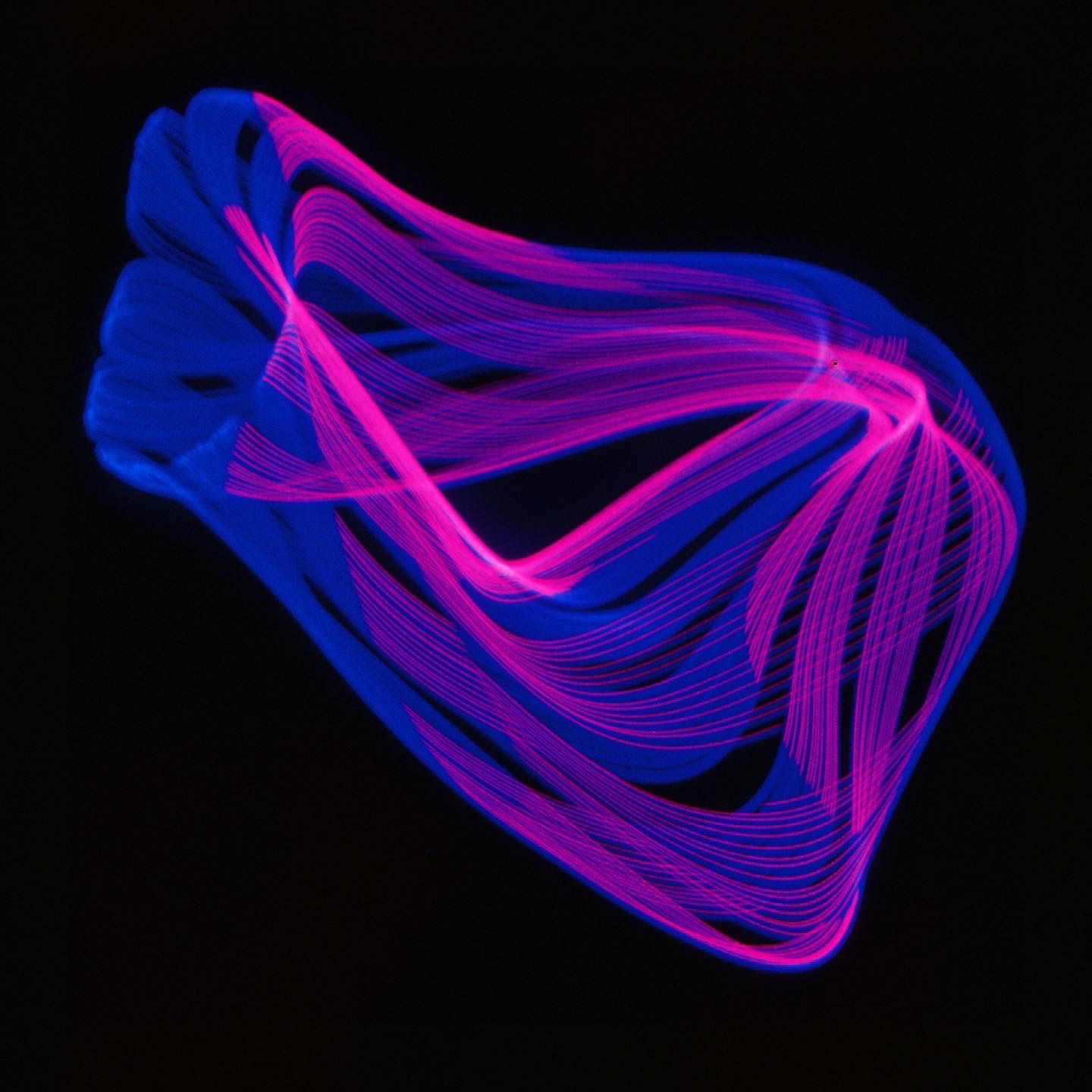

Jacobs’ curiosity extends to Lorenz attractors and chaos theory. “I talked about harmonograms and sound waves earlier, there is a topic I dip my feet into related to that, called Chaos theory. In electronics there exist some special components and circuits that create chaos, a wild signal. If you would listen to this signal, you would hear noise. If I try to draw these signals, I don’t draw figures, but rather a cloud. But if I zoom in to the signal, and use short pieces of it, the fundamental shape of the chaotic oscillator shows itself. These shapes are called ‘strange attractors.’ In science they have been discovering these strange attractors mostly in the 20th century. I say discovering, again, as they are fundamental to nature, and can’t be invented, as they always existed. This beauty is very hidden from the general audience as they are quite hardcore science, but it doesn’t have to be! They are not as scary as they look; they can be quite pretty and are deeply embedded in our nature. It’s not a ghost, I can make it visible and you can look at it.”

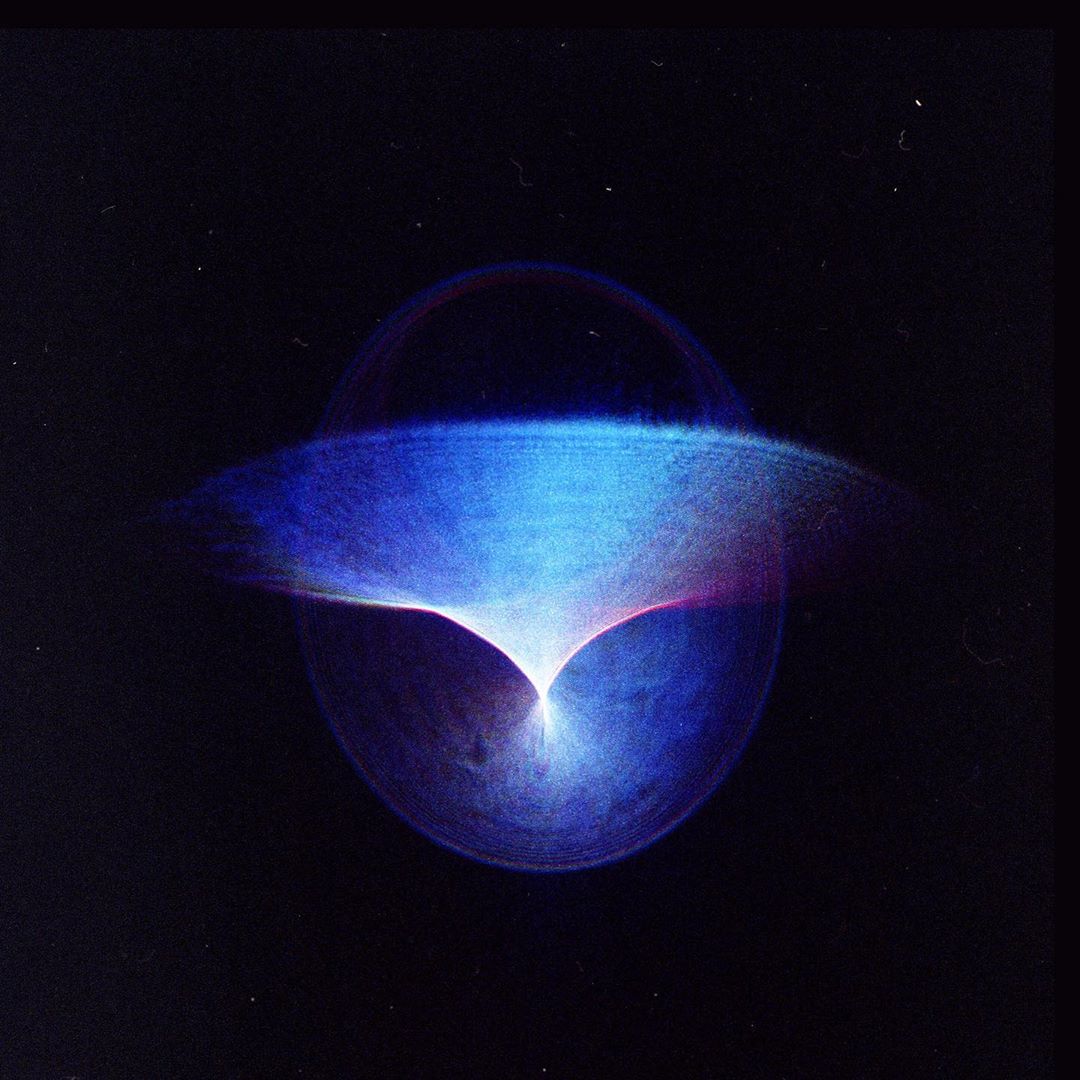

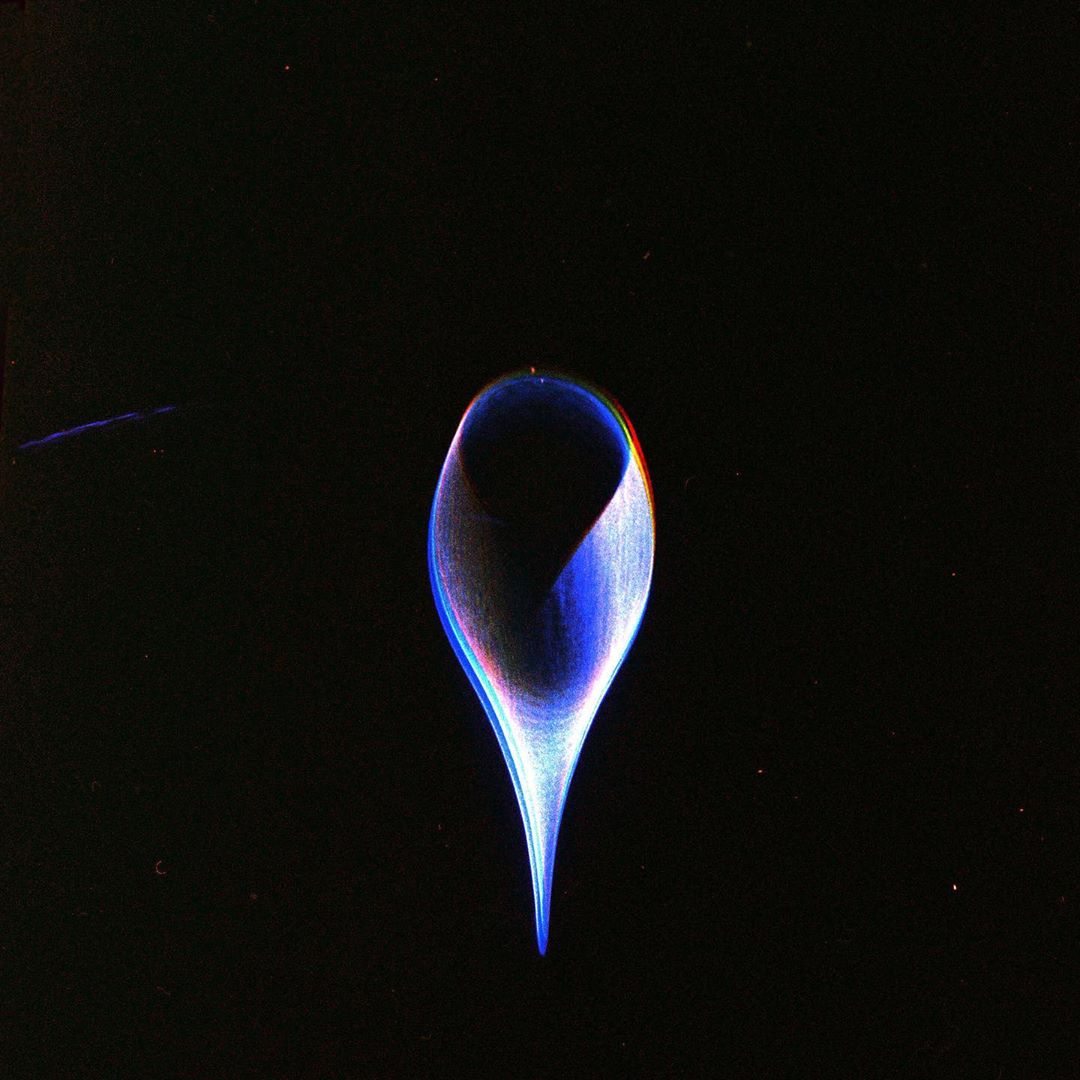

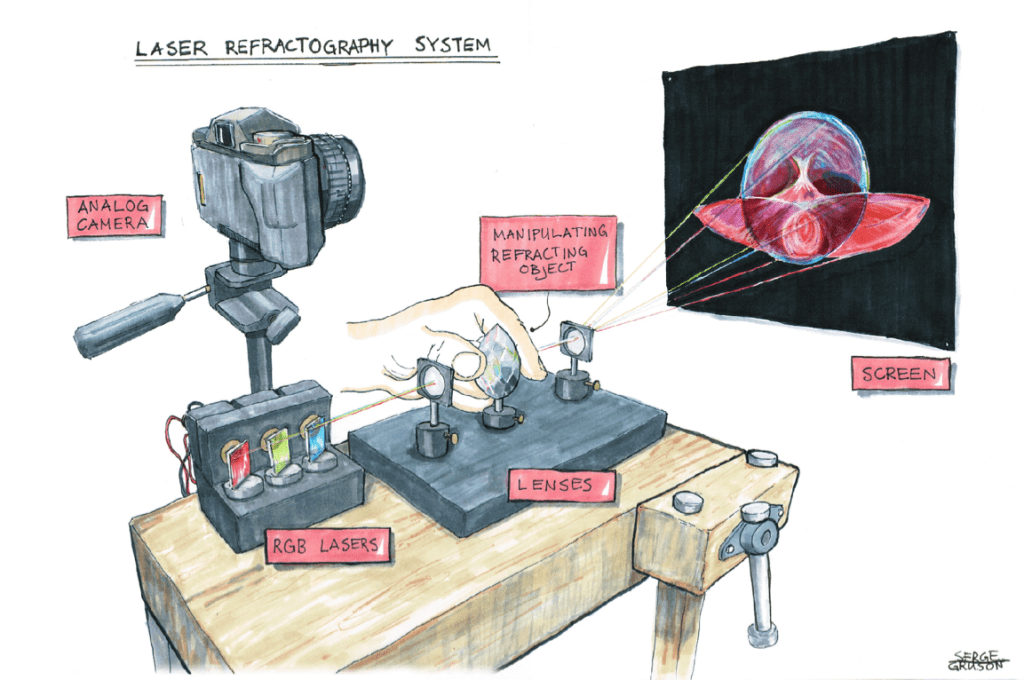

Along with cyanotypes, Jacobs also makes something he calls “light flukes.” These are red, green, and blue light passed through refractory objects like glass or lenses.

“I started a few years ago working with optical modeling software. To design a microscope you need to build an optical model of it. The smallest spot you can project with this optical system are tiny blobs, tiny 3-D shapes. I was looking at these and I thought they deserved more attention. So I made a system that channels 3 lasers into one beam, which I pass through pieces of glass. This creates shapes, which I project onto a background and photograph with an analog camera, which I prefer because they are free of any digital artifacts. These projections, manipulated by hand, only exist for the short time that I can keep my hand in that position, so they are more difficult to ‘catch.’ I use pieces of glass, blown glass, facetted glass, crystals, and lens elements in the beam, and they create a wide variety of shapes. Technical optics make boring shapes; the most beautiful shapes come from antique wine carafes or whisky bottles, which create intricate shapes and constellations, beautiful ghosts.”

Jacobs calls these “cosmic” and once again we get the feeling that he’s captured something elemental, something vital, that’s in all of us, in every living thing, and in the universe itself, on some scale we can’t quite fathom. The images he captures seem to be simultaneously on a smaller scale than we can understand and a bigger scale than we can understand.

“The first art I ever appreciated were the images from the Hubble telescope; NASA photographing nebulas or constellations or galaxies. Something far far away. In my light flukes, the black backgrounds suggest floating in space and remind me of this cosmic dimension. “A theme I have been wondering about for most of my life was what it means to be alien. Humanity has created a lot of implementations of what they think alien life forms would look like, what tools and machines they use, how their motoric and cognitive interfaces work. Yet we have never encountered an alien life form from somewhere else than our earth. So what is truly alien?”

Jacobs finds freedom in art. “When I work for a commercial company I make machines that have to earn money. If I have an idea I have to argue that it’s a good idea, I have to come up with a business plan, I have to prove that it’s financially interesting to research. I can’t say it’s just pretty. In art, I can say I’m going to do this, spend time and money on it, because it’s beautiful, that’s very liberating. My art practice is centered around showing the world that wonder.”

There’s something freeing about doing something just for aesthetics. But Jacobs’ work is beyond aesthetics, because his photographs evoke a sense of wonder, for himself and to share with others. “There are so many things we can’t name, so many ghosts still to be observed and documented. The history of science is biographies of famous scientists, and can be very boring, but in my imagination it’s some kind of a Marvel movie about some kind of scientist superheroes who do experiments and make discoveries and create or define the world around them. It’s a romantic view of the technological world, but at work, I’m very motivated to look for things in technology. It’s part of my daily job to do so, the best is if I can go after something that I discover and not have a business plan about it. That’s the liberating part.”

Photography involves a lot of technology and skill. At some stage in the process, for Jacobs, science turns to art. “My creations are multi-staged. First I create a platform, a stack of technologic capabilities, and the knowledge of the controls. The same way as they first had to create a piano, to play the tunes on that they were until then just imagining. When the instrument is done, the art begins. Of course, there are some iterations. But I like to switch between this analytic and artistic approach. Intuition is such a powerful force in me, in the human brain a lot of stuff happens unconsciously, and I can’t let that go to waste.”

Photography has always involved technology and chemicals, it’s always been a scientific process, and there’s always been a balance between beauty and technology, but we’ve gotten away from exploring that balance. Ralf Jacobs’ work brings the conversation back to that sense of discovery and wonder. “We’re not ready with photography, we’ve only been doing it for 200 years. There is so much to be done. The laser is an invention from the 1960s. It’s new technology, it’s quite alien and otherworldly technology if you learn how a laser works, but you don’t have to be afraid of it. It’s just a thing that emits light. You can explode and vaporize things with it or you can draw with it on paper.”

Ralf Jacobs lives and works in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. See more of his work at ralfjacobs.net and on Instagram at raaaaaaaaaalf.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, photography