The philosophical subject is as follows: A whole society hurling itself at the cunt. A pack of hounds after a bitch, who is not even in heat and makes fun of the hounds following her. The poem of male desire, the great lever which moves the world. There is nothing apart from the cunt and religion.

Émile Zola

Emile Zola’s Nana follows the career of the titular character, Nana, from talentless but intoxicatingly fascinating young actress to oddly addictive courtesan with all of Paris at her feet. We see her go through numerous lovers, some foolish, some abusive, and we follow her to her horrible death of a disfiguring disease. It’s hard to spend too much time in Nana’s world. None of the characters treat her very well, and neither does Zola himself. It’s not just that he’s cruel to her with the plot, although he is. He’s not kind to her with his words, or with the words he has her speak.

I don’t think it’s intentional on his part. In his confused and misguided way, he wanted her to be a sympathetic character, he didn’t want her to be held responsible for all of the destruction that occurs. In his notes about her, which he assembled before he wrote the novel, he describes her as “… good-natured above all else. Follows her nature, but never does harm for harm’s sake, and feels sorry for people.” But just as she becomes “… a ferment of destruction, but without meaning to, simply by means of her sex …” she also becomes a character Zola can’t completely realize or embrace because he knows he doesn’t understand her and he fears her power. He describes Nana as a “poem of male desires,” but it’s female desires that confuse and frighten him, and that he punishes with a disease that makes Nana grotesquely ugly before it kills her. “What lay on the pillow was a charnel house, a heap of pus and blood, a shovelful of putrid flesh. The pustules had invaded the whole face, so that one pock touched the next.”

Zola would probably describe his style of writing as very straightforward and unadorned, almost documentary. He published a work called The Experimental Novel around the same time that Nana came out, in which he said that “… imagination had no place in the modern world, and that the novelist, like the scientist, should simply observe and record, introducing characters with specific hereditary peculiarities into a given environment — just as the chemist places certain substances in a retort — and then noting down the progress and results of his “experiment.”

Zola did much research before he wrote Nana, he interviewed people who moved in the world of actresses and courtesans: All of his sources were men. He wrote copious notes on each character, and his notes on Nana herself are revealing and difficult to read. “At first very slovenly, vulgar; then plays the lady and watches herself closely — with that ends up regarding man as a material to exploit, becoming a force of Nature, a ferment of destruction but without meaning to, simply by means of her sex and her strong female odour, destroying everything she approaches, and turning society sour just as women having a period turn milk sour. The cunt in all its power; the cunt on an altar, with all the men offering up sacrifices to it. The book has to be the poem of the cunt, and the moral will lie in the cunt turning everything sour. As early as Chapter One I show the whole audience captivated and worshipping; study the women and the men in front of that supreme apparition of the cunt. … Don’t make her witty, which would be a mistake. She is nothing but flesh, but flesh in all of its beauty. And, I repeat, a good-natured girl.”

Don’t make her witty, which would be a mistake. She is nothing but flesh, but flesh in all of its beauty. And, I repeat, a good-natured girl.

So Nana reacts to the world around her, and vice versa, because of “hereditary peculiarities” and because she’s a woman. But of course, a novel isn’t scientific, and relations between anybody, either real or fictional, are never predictable. A novel is art, and there is no art without imagination. And a novel tries to represent life, and there should be no life without imagination, either. Even in reality, we create the people in our life. We take notes on their character, we make decisions about them and expectations about how they’ll act. And sometimes we’re not kind about it, particularly if we don’t understand them or fear them because they’re different from us.

Less than a century after the publication of the novel, the real life of artist Niki de Saint Phalle had strange similarities to the fictional life of Nana. They were both born in or near Paris to abusive parents, though Saint Phalle’s family was aristocratic and Nana lived in poverty and squalor. Both were sought after for their beauty — Saint Phalle worked as a model in New York City in her late teens, and even when she became an artist her appearance was often more discussed than her work. They both had many lovers, though both seemed ultimately alone. They both left their children to pursue their career. But Saint Phalle was the author of her own life, not an experiment of somebody else. She had her difficulties and her depressions. When she was hospitalized for what they called at the time a nervous breakdown, she was introduced to painting and she saved herself with art.

She is considered an outsider artist because she had no formal training, and she worked to the motto “technique is nothing, dreams are everything.” She created art with incredible energy and passion because she needed to. As her granddaughter explained, art was her lover and her work. Art was her life. In the early sixties, she rose to fame with a series called “Tirs,” in which she shot guns at paintings, and created events at which others could shoot at paintings. She designed a way to make the artwork bleed paint when it was hit with bullets. Even in the face of her anger and her passion, it was often her attractiveness that was written about and commented upon. “Performance art did not yet exist, but this was a performance. Here I was, an attractive girl (if I had been ugly they would have said I had a complex and not paid any attention), screaming against men in my interviews and shooting.” But for her, the process was important, not sensational. She was killing her demons, and she describes it as a trance-like experience. “I was shooting at myself, at society with its injustices, I was shooting my own violence and the violence of the times.”

She made dark, wild, chaotic art that questioned the roles of women in society and in her own life. She made lifesized brides, emaciated and tragic, with pale staring faces. She made terrifying, strong, monstrous, beautiful sculptures of women giving birth. And she made Nanas.

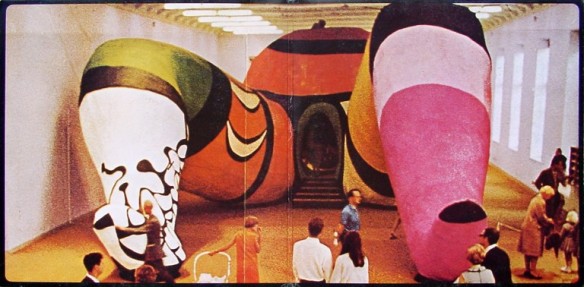

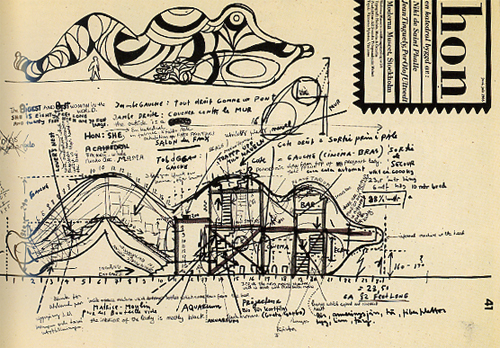

Her career took a shift in the mid-sixties, and she devoted the rest of her life to making larger-than-life sculptures of women that she called Nanas, after Zola’s character and after the slightly rude slang term for women that the novel inspired. She used papier-mâché and cloth at first, but the materials became more and more solid and lasting as the Nanas grew larger, and she worked in weather-proof polyester resin and fiberglass. The Nanas are brightly-painted voluptuous women. They are substantial, fundamental, and, above all joyful — she describes them as powerful because of their joy. They dance and flip and fly, defying gravity and expectations. At one point she made a 90-foot Nana named Hon, which she called the world’s largest whore. People could enter her through her genitals, and she contained a playground slide, a sandwich-vending machine, an aquarium, a movie theater, a museum of unreal art, as well as a milk bar in one breast and a planetarium in the other.

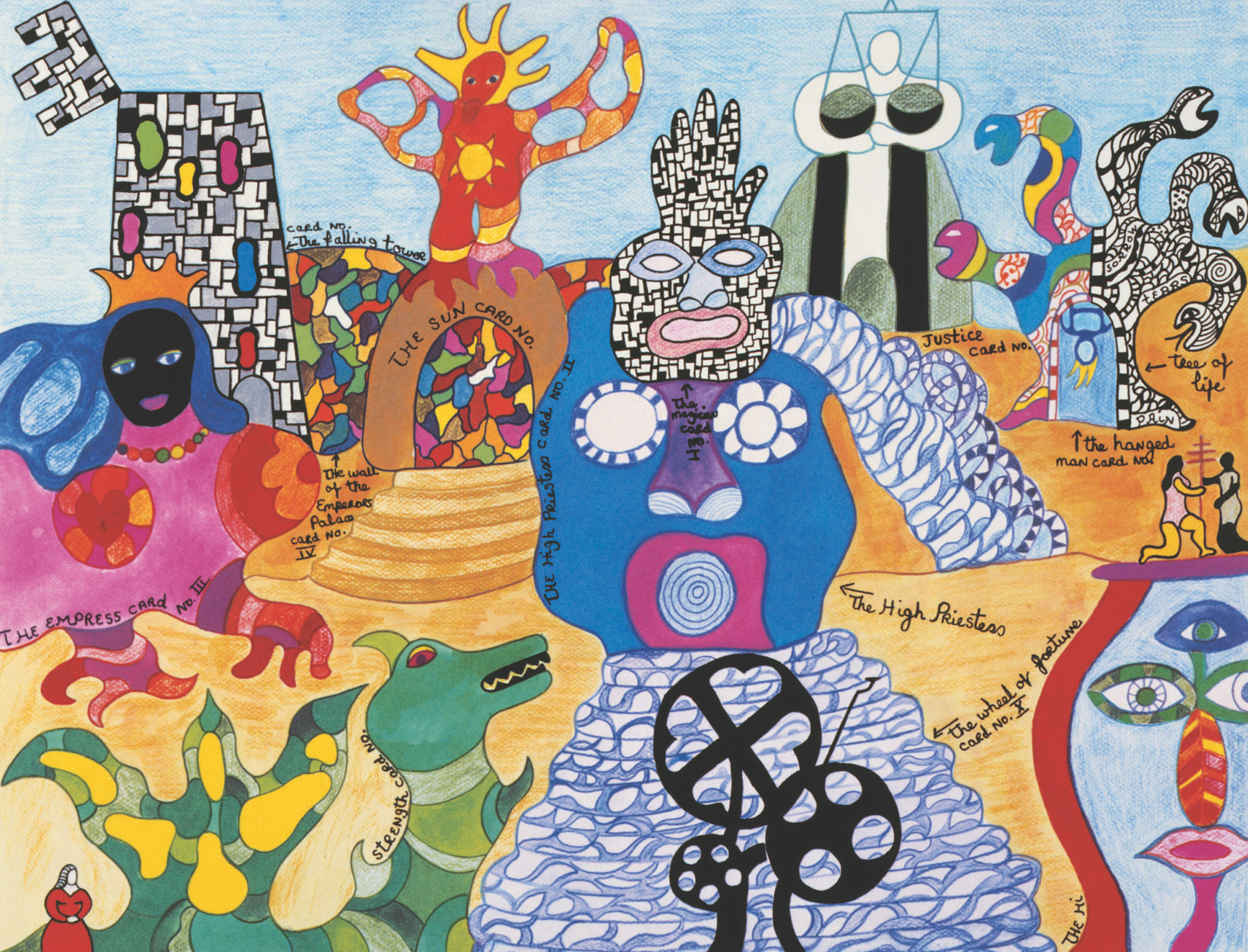

She spent much of the last decades of her life making an outdoor sculpture garden in Tuscany called The Tarot Garden. It was inspired by Gaudi’s Parc Güell in Barcelona, which had made a profound and enduring impression on her. “I met both my master and my destiny. I trembled all over. I knew that I was meant one day to build my own garden of joy. A little corner of Paradise. A meeting of man and nature.” Her garden would eventually be full of giant creatures, some frightening and monstrous, reminders of her early work. But mostly it was full of these Nanas, these giant female figures. One giant figure, “The Empress,” shaped like a sphynx, became her home and her studio for a period while she was working on the park. When asked if these Nanas were a portrait of herself, Saint Phalle answered, “Yes, of course, I am all of them.”

Traditionally “feminine” arts are supposed to be small, pretty, and not demand too much attention. Like women themselves, their artwork was supposed to not take up too much space or cause too much trouble. Saint Phalle turned all of that on its head — literally. Nanas take up space unapologetically. They have weight and worth. They ask many questions, and they make a grand statement, in a loud clear joyful voice. The cunt in all its power, and the flesh in all of its beauty: powerful, witty, exuberant and fully alive.

Categories: art, featured, literature