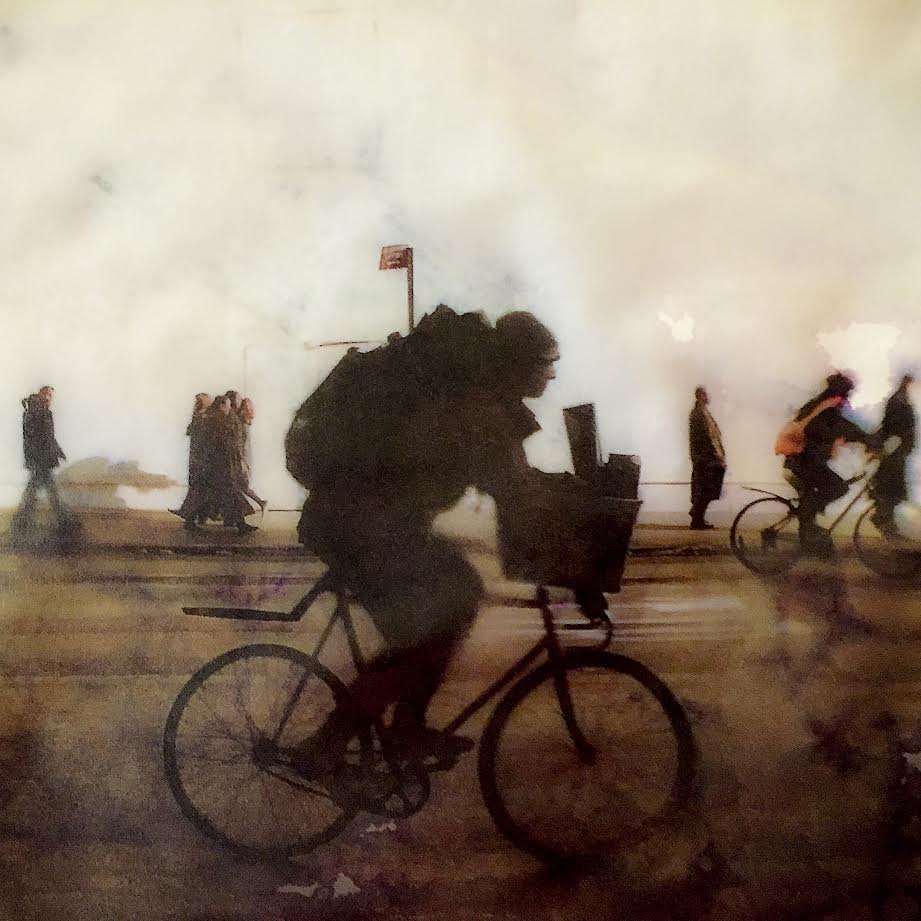

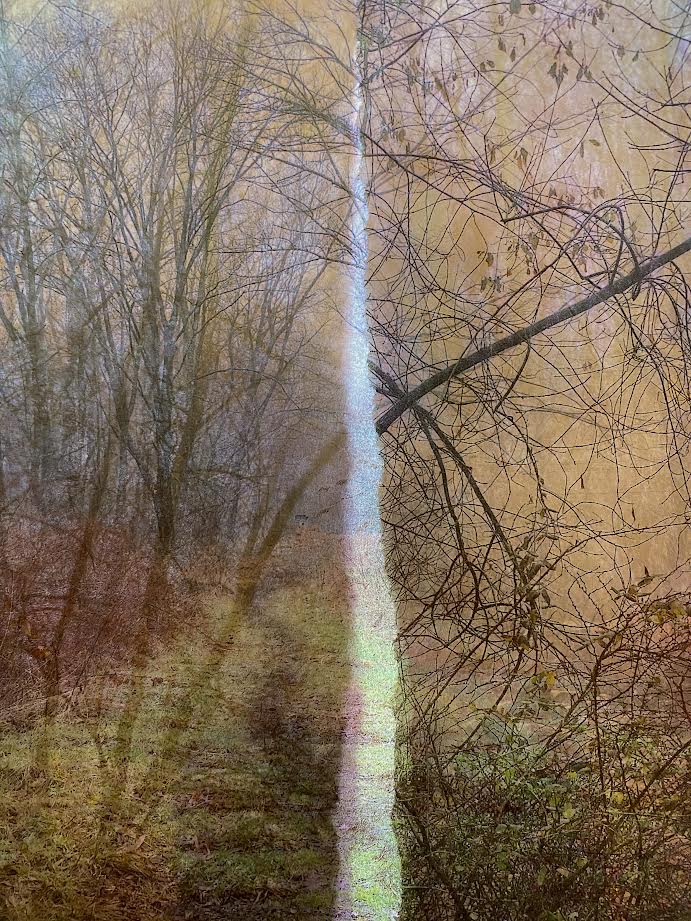

Matt Roberts’ work seems to discover the essence of photography–a captured moment, a slanted memory, a materialized slice of dream. Under the painterly layers and textures, and despite the fact that people are often not the focus of the image, there’s a warmth of humanity. Even the images of busy city streets or crowded beaches have a thoughtful glowing stillness at the center. We were grateful for the chance to ask him a few questions about his work.

This is a little hard to articulate, and possibly hard for you to answer, but here goes…

There’s something about your images I find unusually moving. It’s that sense of watching fellow humans go about their day and then a stranger’s small expression or gesture will give you this pang of some indefinable emotion: Some mixture of recognition, sympathy, not pity (though that creeps in too) and a sense of affection verging on love.

Is this something you’re aware of when you compose or capture shots? Is this calculated? Is there a method involved?

I’ve always been drawn to the seemingly mundane – moments which, on the surface seem to lack drama, but which on closer examination, can be fraught with meaning. A gesture or a glance that can hopefully resonate with the viewer and that can hint at narratives that they are free to fill in as they see fit. I don’t have an agenda when I go out shooting – no “Today I’m looking for an image of ____.” I like to think of photography as an improvisatory act. Though I have no plan when I set out, the fact that there is some continuity of content and execution in my work must mean that the unconscious is at play, revealing even to me what I grapple with or care about.

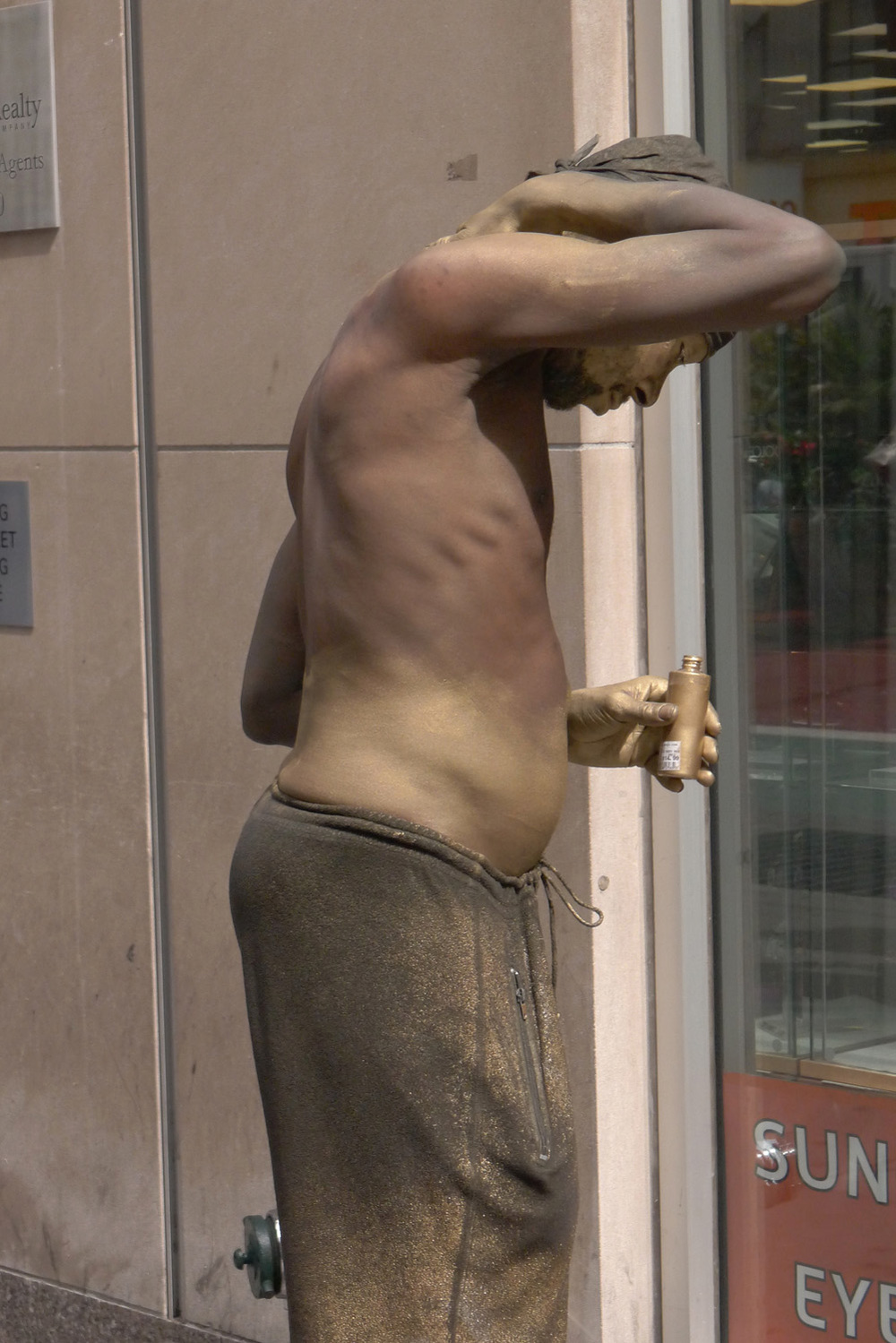

I really loved your video Water Bottle, and it seemed to give me a different way of looking at the rest of your work. There’s such an expectation for art to focus on the figures in the composition. But in this video, and many of your photographs, the humans become part of the background, caught in fleeting glimpses. It evokes a powerful sense of the strange rate that time passes in other peoples’ lives. Can you talk about the idea of shifting the focus from the expected subject?

Similar question, but more about the actual focus of the images—about what is in focus and what is not. I’m reading Bernice Abbott’s introduction to The World of Atget, and her description of his vision of Paris reminded me of your vision of NYC. Many of Atget’s images have sort of ghostly creatures in them–I’ve always assumed it was because the long exposure didn’t allow for the movement of dogs or horses or people with no time to pose for a photograph. But in many of your photographs people are deliberately (and beautifully) out of focus, or seen in reflections, puddles, plastic wrap, or a blur of movement. I’m curious about your idea of capturing people and documenting the world that we live in.

I like to occasionally incorporate people as minor “actors” (accomplices?) in my photos. We humans are just part of the overall landscape, after all. At the same time, the figures in my photos often reflect a sense of alienation or loneliness that seems to be a central theme in my work, one that I hope is still imbued with a sense of the essential sweetness of life.

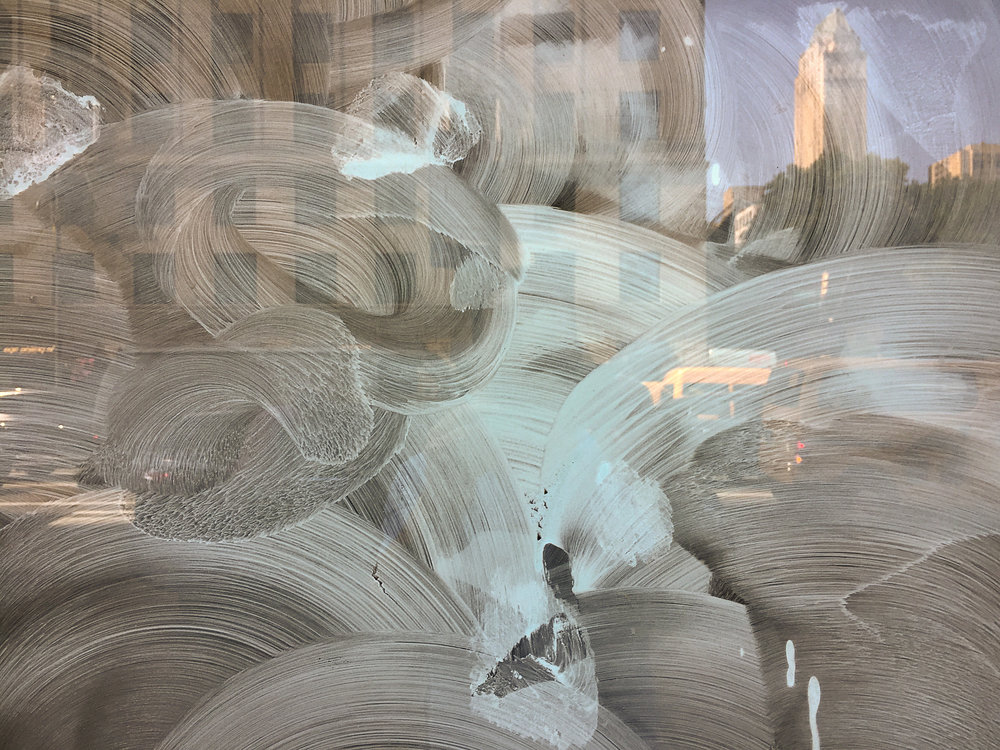

Part A. These textures—slick streets, screens, torn cloths, wooden barriers—lend a very painterly feeling to your work. How do you incorporate texture and surface into the composition of your photographs?

Part B. Same question but about the reflections, windows, water, glass, which create an extraordinary depth to your images. We might look through one window and catch a glimpse into a bank of windows across the street behind the viewer, or look through the windows of a moving car or bus and into the windows beyond it.

While photographs are (generally) two-dimensional, that doesn’t mean they are lacking in texture, depth, or layers. Those characteristics are often present (even if only through illusion) and can add subtle mystery to the image. And while reflections have become a bit of a cliché in photography, windows when used subtly, can serve as a frame, a portal, a mystery, an invitation to view something familiar in a new way.

Your work brings to mind many photographers I greatly admire, including Abbott, Atget, Vivian Maier, and Helen Levitt. What photographers/filmmakers/painters inspire you?

I have been inspired by the work of so many photographers – Helen Levitt for her lyricism and her empathy and lack of judgment for her subjects; Fred Herzog for his way-ahead-of-their-time color images of Vancouver; Saul Leiter for the poetry he found in the most ordinary situations; Dave Heath for the remarkable variety and emotional power of his work; Roy DeCarava for the incredible grace and dignity with which he viewed his subjects, Mike Brodie who published an incredible diary of his life on the road and then abruptly abandoned photography (our loss.) Do these choices make me old-fashioned? Perhaps. I do know that I don’t like one of the trends in contemporary photography towards overly conceptual work (as exemplified by too many of MOMA’s annual New Photography exhibits) that requires a backstory to be understood. Photography IS a visual art, after all, and is one that should resonate with the heart as well as the brain.

Photography IS a visual art, after all, and is one that should resonate with the heart as well as the brain.

I’ve loved movies since the days of watching Million Dollar movies on local NY tv in the 60s as a kid. Some favorite directors: Vittoria De Sica for his humanist neo-realist dramas with post-war Italy as the backdrop; Frank Capra for his heartwarming, everyman characterizations; Alfred Hitchcock for the sheer joy he brought to filmmaking.

You’ve been active in photography for a few decades, and the world of film and photography has changed fundamentally in that time… from a pursuit that required skill, time, and money, to something everyone can try if they have a phone in their pocket. How do you feel about this shift in the art and technology of photography? How have you adapted your method and process?

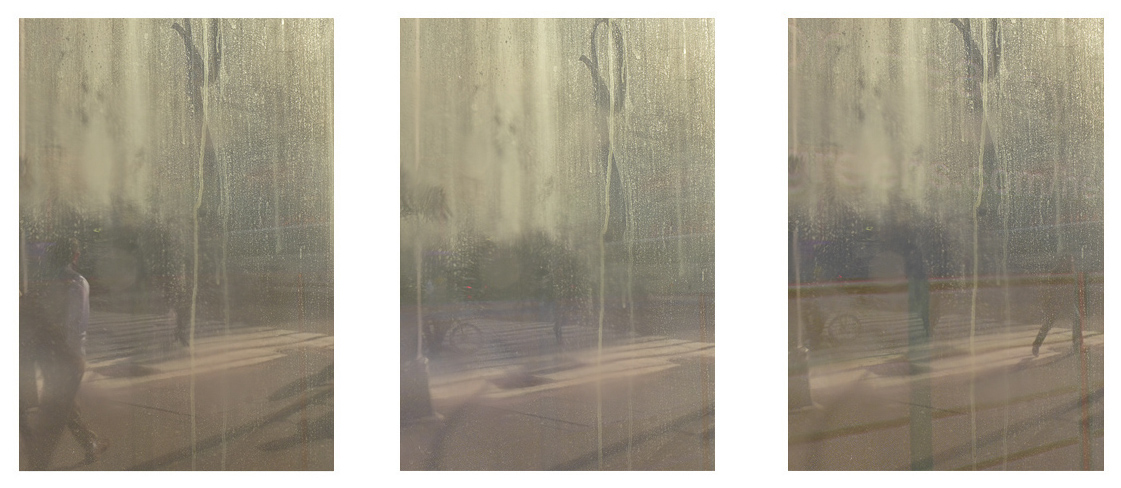

The advent of digital was a two-edged sword. More opportunities to be seen, but more opportunities to be lost in the shuffle. One clear advantage is that you can now shoot ‘til the cows come home. In the old days, I had to limit myself to one or two rolls of 36 exposure Tri-X per day for cost reasons. And of course, sometimes outside events force one to adapt their methods and processes. During Covid I had to turn a bit inward – both physically and metaphorically. Because I couldn’t go out shooting as much, I started revisiting/re-inventing old family photos, images I had taken on trips into NYC, backyard photographs, etc. I would print the photos on cheap copier paper, manually degrade them in the kitchen sink, and then rephotograph them, often in layers or grouped in diptychs or triptychs. It is a low-tech, primitive technique, but one that I am continuing to enjoy and pursue, even though our movements are no longer restricted by Covid.

Your images of the city combine: The present and soon-to-be-gone (advertisements, plastic bottles, billboards for musicals); the past (the structures of the buildings and streets and everything stone and glass and concrete); and the soon-to-be future (people hurrying somewhere, growing and aging).

This brought to mind a quote from Berenice Abbott (sorry, I just love her!) “The photographer’s punctilio is his recognition of the now—to see it so clearly that he looks through it to the past and senses the future. This is a big order and demands wisdom as well as understanding of one’s time.”

Is this something you think about in your life and your work?

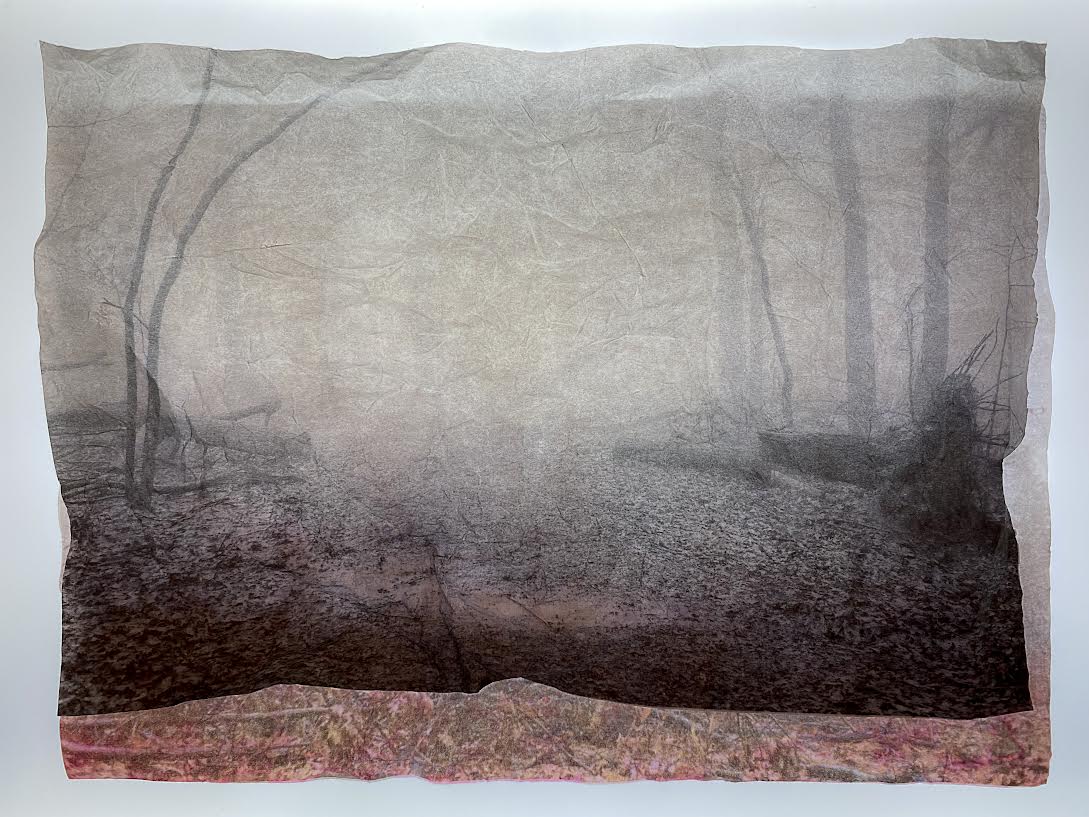

I have always been sensitive to the passage of time, sometimes painfully so. I remember at age 12 feeling that the years were starting to go faster than they were when I was six. So the sense of the ephemeral quality of life and the knowledge that the present and soon-to-be-gone can inhabit the same frame may come to play in my work. I have always admired how Atget and Walker Evans, in addition to being great artists, were devoted custodians. They were determined to preserve things they cared deeply about – a city, architecture, a way of life. My goals are less lofty – I want to preserve things I like to look at (Gary Winogrand once famously said that he photographs things to see what they look like as photographs.) The question is what to do with all the pictures I’ve made in almost 60 years of practicing photography. There is no more space under the beds or on closet shelves.

I wonder about the art of finding the beauty in the discarded or the everyday and overlooked. A plastic water bottle, a glimpse into a construction site, a rainy car window at a certain time of day, warped metal, plastic buckets on an empty beach. Can you talk a little about how that becomes part of your work?

I suppose I have always had empathy for the discarded and have tried to find a sense of beauty in loss and decay. Of course that can lead to a certain somberness of tone and content, one that might lead viewers to think I am a sadder person than I actually am! Interestingly, I have taken several memoir writing classes in the past few years, and my writing is pretty light and humorous. Maybe it’s a way of expressing two sides of my personality and perhaps it is easier or more natural for me to express painful feelings in photography rather than writing.

Matt Roberts is a New Jersey-based photographer and collage artist who has been active in photography since the 1970s. He studied photography at Hampshire College and in the MFA program at Pratt Institute. All of his work, whether it is in the genres of street photography, landscape, or family portraiture, is concerned with capturing moments, which while inherently “small”, convey an emotion – a sense of yearning, alienation, joy, or the simple pleasure of seeing something familiar in a different light.

A three-time recipient of individual Fellowships from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts, his work has been shown in a wide range of venues in New Jersey, as well as in group shows in museums and galleries in New York, Rome, Boston, Philadelphia, Vermont, Colorado, and Oregon. You can see more of his work on his website and on Instagram at mattrobertsphotog.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, photography