An Inteview with Karl X Hauser

by Andrew McAleavey

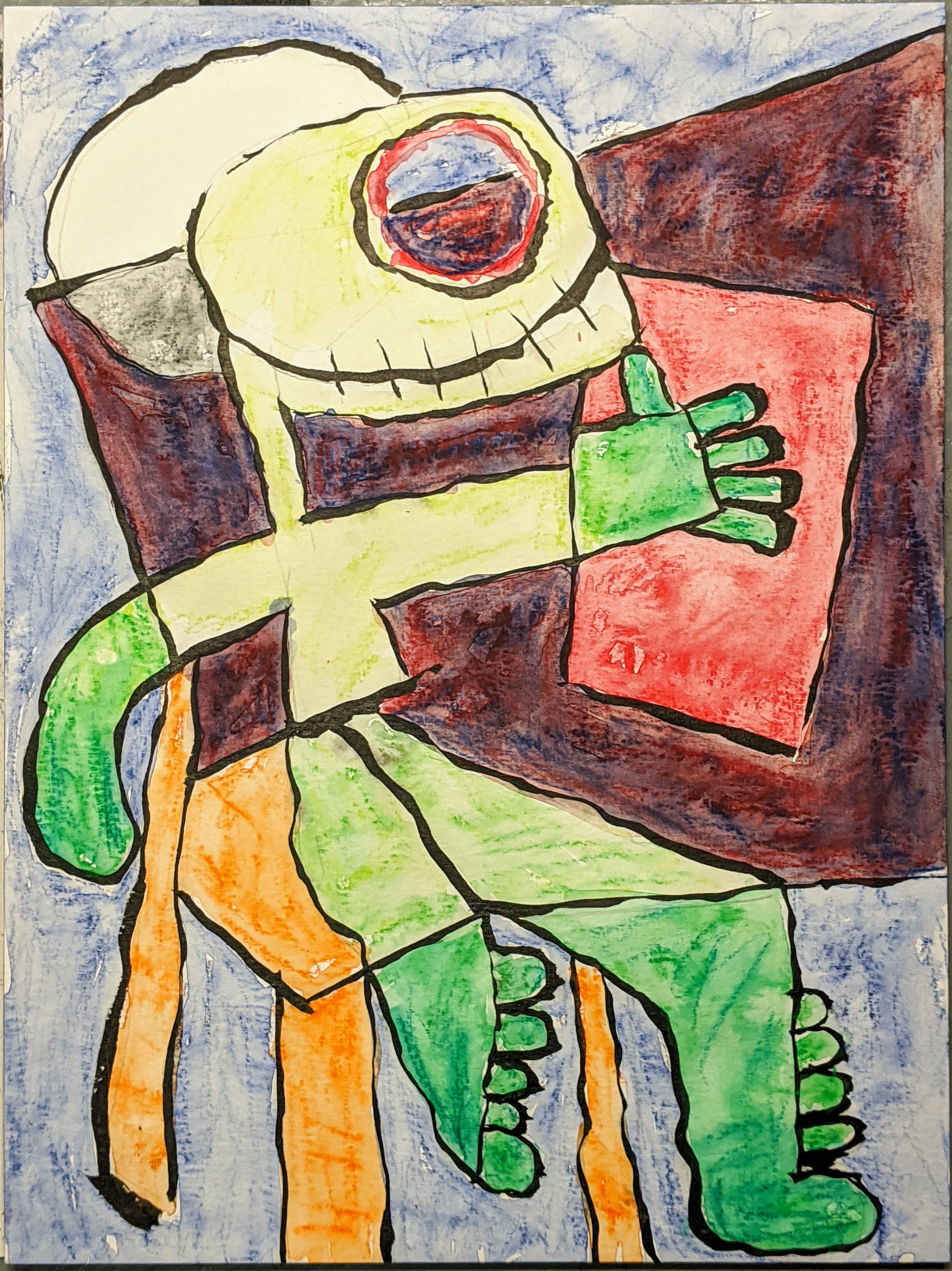

“Fever Dream” is a deeply ironic descriptor of Karl X. Hauser’s work. The term connotes illness, psychosis; it’s rife with otherness. In lucid moments, we slough off such things, relegating them to the deepest recesses of our subconscious. Calling this work a fever dream, invoking otherness, risks letting the viewer off the hook too easily – Hauser’s work is deeply relatable, taking on our world in skewered perspective with raw honesty and emotional range. Yet it’s that very sense of otherness, that playful, otherworldly audacity in his work, that lets him get away with it all.

That something is often juxtaposition, contrast: of color against black, of texture against void, of noise against quiet, of sharp against soft, and perhaps most vividly, of anxiety, darkness, and horror against love, playfulness, and connection.

“I want to believe there’s hope. It’s important to recognize that there’s darkness too,” says Hauser. In both hope and darkness, connection is important to him – “I do something to engage [the viewer].” That something is often juxtaposition, contrast: of color against black, of texture against void, of noise against quiet, of sharp against soft, and perhaps most vividly, of anxiety, darkness, and horror against love, playfulness, and connection.

“the mirror stares back” may be a perfect example: in a void of contrast noise, two figures face each other, each one drawn within a loose, brightly colored rectangle. Their expressions are replete with joy. There’s something recognizable, even approachable, about the scene. The bright palette, simple forms, and visible strokes evoke deep, pleasant echoes of childhood and reinforce the joy we see in the scene. The ease of the visual style is both sincere and a sleight of hand – something deeper lies beneath.

The figures are neither flat-stick nor perspective-drawn, their forms suggestive but unreal. A central internal structure—a skeleton?—is visible within each figure, but is rigid, incomplete, and incompatible with movement. Altogether, the figures radiate a fervid strangeness, leaving the viewer to grope for a visual analogue with which to understand them – a blurry x-ray, perhaps, or an amoeba seen through a dusty microscope.

The title of the piece adds another incongruity: are those loose indigo and green rectangles mirrors? Are the two figures in fact a single figure, looking at its reflection? That cannot literally be true: the two figures may echo each other in Hauser’s sly, easy style, but they are not reflections of one another. We quickly find ourselves in hypnagogic territory, sorting real, unreal, and surreal at the edges of a dream.

Or is this dream a nightmare? The figure on the left seems to have broken out of its mirror, its hand bandaged. Despite their joy, the figures are held apart from one another. At one corner, the two mirrors appear to intersect, their intersection rendered as noise that breaks from the color and harmony around it. Are we seeing these figures an instant before the mirrors shatter, he figures are annihilated, and everything is absorbed into the void? If Hauser knows, he’s not (quite) telling.

Like much of Hauser’s work, “the mirror stares back” balances joy, wry humor, strangeness, and horror in a single piece. That balance is critical – the work may be dark, but it is never bleak. “People want good news too!” he says.

An Artist of Every Medium

“Medium is not that important to me,” Hauser says. He’s drawn from an early age, trained as a sculptor, pioneered video art when video was in its infancy, constructed complex, computer- driven neon art long before computer interfaces were mature, made neon signage, and worked in a metal foundry. If he has easy access to it, he says, he’ll use it to make art.

Hauser’s world may manifest somewhat differently in different media, but the same elements, the same balance, remain. Texture is one of those elements. “Our world is filled with texture,” says Hauser, who finds himself studying textures and patterns, even in seemingly mundane things like concrete. In his drawings, texture has a presence: the void in “the mirror stares back” is not empty; it is filled with textured visual noise.

In sculpture, Hauser’s use of texture reaches its fullest potential. “funtime,” for example, presents at first glance a dilapidated roller skate: boot worn and tilted to an ankle-breaking cant, wheels out-of-alignment and seemingly bowed up against the boot’s heaving weariness. After a moment’s contemplation, we begin to see how much texture contributes to the feel of the piece. “funtime” is deeply and variously textured – an odd, thick, cobbled-stone tread on the wheels, and a variegated roughness on the boot make us wonder just what form of creature might have used and abused this skate over its tortured life.

Texture is closely mated with color. Hauser builds color and effect by layering, much like watercolor. A surface might have five to ten coats of different stains and colors. He often colors a deeply-textured surface and then wipes the surface, leaving only the color most deeply seated in the crevices of the texture, before continuing with additional coats. The effect of this is manifest in “funtime”: a boot whose complex, blended, and overlapping blue and rust hues speak to the very dilapidation and unease at the emotional center of the piece; a base seeming to drip messily with blacks and blues, as if dragged unevenly in tar; and wheels embedded with hints of every hue imaginable, leaving us to wonder at their history.

As Hauser steals the iconography of pleasure and play to co-opt it for his own purposes, color and texture aid him in the heist. Protruding from the top of the boot are, at first glance, a bunch of balloons. For these, Hauser has taken and twisted the saccharine positivity of the smiley face into something else entirely. The “strings” of these balloons are coated with reds, oranges and blacks, evoking rust, blood, and dirt. The balloons themselves, while smoother than the boot, are uneven, almost faceted, and as varied in texture as they are in color, with crevice-set deep red defining the faces, and surfaces splotched and smeared with reds and oranges under, over, and alongside the iconic yellow. The result plays on the familiar while taking us somewhere just dark enough to see things in a new light.

Influence and Expression

“Art history is the best place to steal from!” Hauser says, describing with a certain glee “those medieval paintings where people were lined up next to each other, but their feet were all drawn wrong” because true perspective hadn’t yet been invented. He notes Paul Klee’s puppets as a major influence, along with the hypnagogic creativity of the surrealists, and a fascination with the psychedelic. From all of this, Hauser has created a visual language that describes a world just beyond the reach of our own.

Hauser’s visual language is considered and detailed. For example, he most often alludes to human appendages, as with the flowing bouquets of rusted nails that allude to fingers and toes in “fever dream no. 5.” Yet one literal type of appendage pops up throughout Hauser’s sculpture: a set of baby hands. In fact, the same set of baby hands. Long ago, Hauser found a set of baby hands on an Etsy site for people who make dolls. Most baby hands of this type are balled up, he says, but these were an exception. He bought them, created molds of them, and has replicated them in several media, including metal and resin. “They’re expressive,” he says, comparing their emotive potential with that of the eyes.

Hauser shows that, set against the strangeness of his world, those incongruously familiar hands become a fiercely expressive force.

So much of art exalts the eyes that it’s difficult to imagine anything else doing their emotional work, but Hauser shows that, set against the strangeness of his world, those incongruously familiar hands become a fiercely expressive force. In this body of work, we see the hands in a number of sculptures, including “imagining our surprise,” where they’re splayed out in near-shock; in “our fragile prison,” where they’re used more enigmatically, conveying both the physicality of the main figure and a range of emotion; in “the singing lesson,” where the position of the arms and hands mimics that of a choral director and allows the piece to resonate with its title; in “fever dream no. 3,” where the position of the arms and legs suggests a crying tantrum from an infantile figure; and in “our missing shadow,” where the position of the hands and arms suggests a swaggering stride gone awry.

Depending on the sculpture, the baby hands may be placed on much longer, thinner appendages, gloving an otherworldly tentacle, or they may be used with thicker, more arm-like appendages. In “imagining our surprise,” the arms are thin, alien, their meandering shape evoking lightning-shocks of surprise. In “our fragile prison,” the figure’s left arm looks rumpled just above its hand, as if a shirt sleeve were rolled up. In every case, while the hands themselves are recognizable, Hauser adapts them to the piece, coloring and texturing them to fit the reality of the figure. In an artistic style replete with the otherworldly, the baby hands are an evocative tether to the known and a concrete, if backhanded, demonstration of Hauser’s emotional range.

Hauser’s relationship with the human body is just as nuanced, and is just as much a part of the language of his work. His figures are rarely literally anthropomorphic, and many, like those in “the mirror stares back,” are so loosely formed as to invite a smile. It seems that in Hauser’s world, the more there is a recognizable head, the less likely it is to be attached to an anthropomorphic body. The heads of screamers, snaggle-toothed beasts, and imaginary friends alike are installed on wheels, on carriages, and in cars. While Hauser clearly enjoys tinkering with the notion of the body, he insists that this was originally for pragmatic reasons – he once sculpted a bunch of heads he liked, but couldn’t quite get the bodies right, he says, so he got creative. In the full context of his work, that creativity—Hauser’s functional abbreviation of the body becomes another type of visual juxtaposition, often of horror with lighthearted absurdity.

Art in a Time of Anxiety

By 2019, Hauser had been working frequently in metal and fused glass, spending his days at the metal foundries of The Crucible in Oakland, California. As he describes it, “nothing about foundry work is easy.” There’s an exhaustion to the work. By the beginning of 2020, Hauser had also realized the need to have his left hip replaced.

For Hauser, the COVID-19 pandemic and his own health reinforced a natural progression: “You can’t do what you’ve been doing,” he said to himself, “You must do something else!” He began to draw and to work in a home studio. He turned to more prosaic materials: Styrofoam, resin, burlap, and wire, to name a few. These felt familiar to him – he’d often used Styrofoam as a precursor or intermediate in metal casting, and he had long experience with resins as well.

The materials may have changed, as they do periodically for Hauser, but even in a time of anxiety, his purpose and vision did not. “Art has always been therapeutic,” he says, a salve in anxious times, and a way of reconciling the extremes of human emotion.

If anything, his recent work has more immediacy. The austerity of metal was replaced with the greater color and intimacy of Styrofoam-based works. Wire, burlap, and string create deeper and more abundant texture, as in “fever dream no. 5,” where string both defines the body of the figure and suggests a mix of tangled ineptitude, captivity, and fear.

Even though Hauser grapples with darkness and primal emotions in a contemporary world that feels full of both, he denies that his work is meant as social commentary. Any social commentary one might find is “very, very oblique.” Social commentary or not, one thing remains true: in his deft interplay of the prosaic, the otherworldly, and the emotional, Karl X. Hauser is not letting us off the hook.

Artist’s Statement

More than a few things have changed since my last solo show two years ago at the Transmission Gallery in Oakland, CA. Before, I was doing a lot of metal casting but that’s no longer as accessible except for commissions. I’m still using most of the same materials for sculpture that I used as patterns in the casting process but now they play different roles. Styrofoam is my material of choice. It’s super easy to work with and free. In foundry work I would make molds from carved styrofoam for casting in metal. Now, it plays a more direct role and I can work from my garage. I still use my mold library. The castings are now done in plastic. I use the castings with other carved or sculpted elements as one would a collage. I often make multiple elements that can sit around for months, sometimes longer, unsure of what they may become.

I don’t often have plans for what I sculpt. Sometimes I have something in mind and then it takes off in a direction that I hadn’t anticipated. Series arise as a result and sometimes go on for years. After I accumulate a few similar pieces is when I might start to study them in depth. Or I might not pay it much mind until I find myself looking at a new piece and thinking, “Oh, it looks like one of those.” I endeavor to make connections through my work but it’s only right that the viewer feels some of the same things that I do. The subjects need to have a certain appeal to them while also being a bit off- putting. I like contrast or interior conflict in my work. Ambiguity is essential. I try to provide enough recognizable landmarks for the viewer to have some orientation only to have them realize they have landed in a strange land with few guideposts. The viewer is left to find their own way. I do things that tend toward figuration. The figure is a rich source of potential contrasts. Gestures are central. I think of gesture as the projection of a subjective state onto an object so that the object appears to be infused with it. It’s part of the landscape, how I apply color, and the textures I use. Drawing is the place I go when I need new input, but my drawings are rarely things that I plan to sculpt. Drawing puts me in a different place. I’m not concerned with how things go together or how they fit. Drawing forces me to examine minutia. Drawing is the blank page, the void, confronting the fear that’s just beneath the surface. These are the things that inform the sculpture.

Karl X. Hauser

July 2022

Gallery of Work

Karl x Hauser was born in Michigan City, on a small farm in northwest Indiana. He played in the dirt, drew pictures, and learned to swim in Lake Michigan. He attended the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis where he studied sculpture, learned to make neon signs, and was first exposed to video art. He received his MFA in video and performance art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1981. Simultaneously figurative and expressionistic, his work weaves together humor and the horrific. See more of his work at karlxhauser.com and on Instagram.

Categories: art, featured, featured artist, interview

Hey Karl-

I love this stuff!

Can we get a catalogue???

Bob Snyder, Chicago

LikeLike

hey Bob –

Just got a proof back from the printer. I’ll have catalogs in about a week. the cost is $35. + shipping ($15). my email contact is kxhauser@gmail.com

LikeLike