By Alice Courtright

An appreciation of Marina Harss’ biography The Boy From Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet

Last fall, I saw Alexei Ratmansky’s 2009 ballet “On the Dnieper” at the Koch Theater. The one-act story ballet, set in the aftermath of World War One, combined elements of classical and modern choreography. The partnering was full of traditional lifts, but the dancers’ gestures often shifted to the angular and stark. There seemed to be two languages at play: the old tongue of smooth, elegant movement, and a new one, all elbows and distressing emotion. Lovers managed betrayal and desire, and their conflicted feelings poured out in somatic bliss and boxy anguish. One set, designed by Simon Pastukh, conjured an outdoor village scene, with cherry blossom petals covering the stage. The dancers’ spins and steps blew the petals into the air, and they drifted back down slowly, creating a sense of ongoing suspension. There was an ethereal and affective cohesion to the Ukrainian tale. It was mesmerizing.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, photographs of bombed-out cities, refugees clutching their children, and lifeless bodies curled up on sidewalks populate the grim news. When I saw Ratmansky’s ballet, I was filled with dread and anticipatory grief. Ridiculously and anachronistically, I wanted to shout at the characters to leave behind their moody love triangles, pack their bags, and prepare for the greater conflict. Their ceremonies and moonlit encounters were taking up precious time–a future enemy loomed large offstage. As Tolkien put it, a destroyer who would devour all.

The celebrated Ukrainian-American poet, Ilya Kaminsky, writes about power, relationships, civic duty, and war. Looking back through his work, I get the sense: he’s always known the reality of occupation, the threat of invasion, the fault lines of his society. It’s in his poems from the beginning. Ukraine declared its independence after the collapse of the USSR, but the region has been pummeled by war and foreign occupation for centuries. Consider the start of Kaminsky’s foreboding title poem from his first collection Dancing in Odessa (2004):

We lived north of the future, days opened

Ilya Kaminsky

letters with a child’s signature, a raspberry, a page of sky.

My grandmother threw tomatoes

from her balcony, she pulled imagination like a blanket

over my head. I painted

my mother’s face. She understood

loneliness, hid the dead in the earth like partisans.

The night undressed us (I counted

its pulse) my mother danced, she filled the past

with peaches, casseroles. At this, my doctor laughed, his granddaughter

touched my eyelid—I kissed

the back of her knee. The city trembled,

a ghost-ship setting sail.

The women around the boy shield him from the reality of the trembling world. Imagination is a “blanket/over [his] head,” the past retroactively filled with sweetness. But the real city is full of skeletons, a “ghost-ship” in the middle of the Cold War. The land is haunted by ongoing violence. What does it mean to record intergenerational relationships, a kiss on the back of a knee, with so much destruction at hand?

Kaminsky is now a professor at Princeton and he traveled back to Odesa this winter to support his organization, “Poems against Missiles.” Their website says: “We believe poems can allow young people to articulate themselves when they are alone, when they are in bomb-shelters, when nothing else is there. Poems can also help community to come together in Odesa streets, words allow neighborhoods to keep their humor alive, their spark, their music. Despite the destruction, people of Odesa need literary arts now more than ever.” Kaminsky is also documenting the war tactics of the Russian military: bomb once, wait for the first responders, bomb again.

The biography became, in effect, two stories: one, in which Harss deftly traces the formative patterns of Ratmansky’s distinctive and prolific career, and a second shadow story, in which Harss herself grapples with the unfolding conflict, the changing international landscape of the ballet world, and, most compellingly, the shifting identity of her subject.

Marina Harss’ new biography of the choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, The Boy from Kyiv, was published in the wake of Russia’s invasion. She was years into her research of Ratmansky’s life and work when the tanks rolled in and the first missiles flew. The biography became, in effect, two stories: one, in which Harss deftly traces the formative patterns of Ratmansky’s distinctive and prolific career, and a second shadow story, in which Harss herself grapples with the unfolding conflict, the changing international landscape of the ballet world, and, most compellingly, the shifting identity of her subject. “I feel it is my duty to support Ukrainian culture,” Ratmansky said to Harss in the summer of 2022.

The winding of the two stories together is evocative. The rigorous, objective work of a biographer collides with the biographer’s stunned reaction to unfolding world events. Suddenly, she, the distant observer, was almost forced onto the stage herself. You can see the wheels turning: had she really just been in Kyiv, meeting Ratmansky’s parents and sister? How were all these people who had welcomed her, and shared their cherry wine? How would she integrate this news into her crystallizing book? More importantly, what did she think about it? Harss’ language is never sentimental, but a sense of shock hovers over the concise prose, and a growing defiance.

The biographer stands with her subject, seeming to quietly declare, This unprovoked attack is wrong.

Harss qualifies many sections of her writing — “How this will change in the future, in light of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in 2022, is still to be seen.” But these addendums don’t come across as afterthoughts. Rather, they give the book a kind of electricity. This is a book of the moment. The future is not simply unknown; it has fundamentally shifted. Every carefully crafted page had to be reexamined, like a piece of pottery taking on one final glaze. A Boy from Kyiv emerges like a precious artifact: here is the record of an artist up to a very specific and charged moment in time. Oral histories could be lost at any moment. The biographer stands with her subject, seeming to quietly declare, This unprovoked attack is wrong.

Harss is an accomplished translator. Her fluency in several languages and ease in switching between cultures lend Ratmansky’s complex life story a necessary sense of readability and explanation. She’s a trustworthy guide. A Boy from Kyiv is a fast-paced book, mirroring Ratmansky’s own trajectory. He’s one of those artists it’s hard to pinpoint. First, he was here, but he was really from here, and then he was here, here, here, and then… a narrator could give up easily—there’s too much to explain. But Harss manages the biography patiently, separating out phases and explaining clearly the divergent and international nature of Ratmansky’s chapters. She can keep up and she wants to bring the reader along. It seems a privilege to sit in ballet studios and the Houghton Library archives with her. She flies across the world to get the interview quotes that make the biography feel like a living creature. She takes time to deliver exquisite passages of dance writing. By the end of the book, though, I was a little breathless. Ratmansky has created hundreds of ballets and often has only two or three weeks to make each one. Reading about his life was astonishing in its capacity, and a bit overwhelming. I made a cup of tea and put a blanket over my lap. I wondered about my own creative capacity: what’s possible?

Ratmansky began as a young student at the Bolshoi, but worked as a dancer at international companies in Kyiv, Winnipeg, and Copenhagen, rising to principal three times. He amalgamated his choreographic style from this cumulative formation, grounded in the rigid Russian classical tradition and influenced by the contemporary methods he encountered elsewhere. In Denmark, he was struck by the lightness of the dancers, and the ongoing use of mime. Because of the way Ratmansky mixes contrasting styles, “emotion blossoms in unexpected ways,” writes Harss. Joan Acocella put it this way: the dancing is “classical–the dancers did regular ballet steps–and yet touchingly natural and intimate.” Harss helps the reader understand, ballet by ballet, how Ratmansky revives and captures the affective life of his specific characters. In Sleeping Beauty, “In the famous wedding pas de deux,” Harss writes, “There is a moment in which the princess, Aurora, advances toward the prince with tiny fluttering steps. In most productions, she dives into a downward-leaning arabesque, a streamlined, elegant shape. Here, instead, she embraced him warmly, resting her head tenderly on his shoulder. She was not just a ballerina but a woman in love.”

Throughout the biography, Harss documents Ratmansky’s commitment to the particular and the human.

Throughout the biography, Harss documents Ratmansky’s commitment to the particular and the human. Ordinary cross-cultural discoveries alchemize into poetry. When his wife, Tatiana, in Winnipeg, finds whipped cream in a can, she can’t get enough. The Canadian “supermarket was two miles from the company studios, and she would run there between rehearsals to buy a can.” Ratmansky made not one, but two ballets based on this private moment of delight.

From the beginning of his choreographic journey, Ratmansky invited the audience to specific moments of playfulness. In an early work, La Sylphide, specific, humorous details in the choreography mock male egoism and the trenchant soviet state. One critic wrote, “For the first time in half a century…the Moscow public laughed out loud at a classical ballet.” Playfulness, to Ratmansky, was not only a way to share joy, but subversive, marking a new era of artistic freedom.

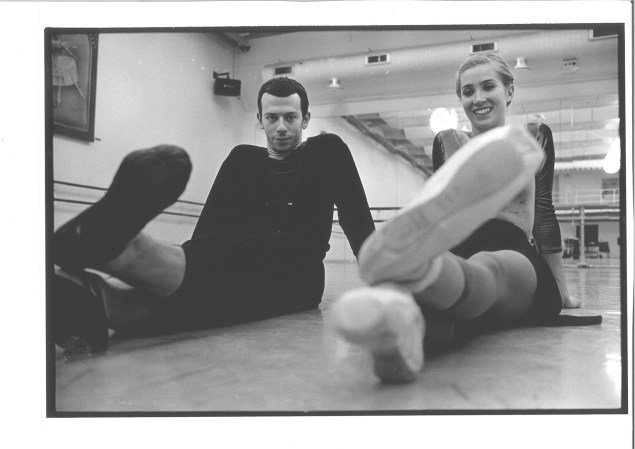

Ratmansky has a willingness to learn and be led. During his tenure at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, Ratmansky was partnered with the long-time star Evelyn Hart for a performance of Giselle. “He saw how she analyzed every detail, from the quality of the transitions between the steps to her relationship to the floor when she rose onto and descended from pointe,” Harss writes:

‘She wanted to make everything soundless and light as a feather, so she would soften her point shoes until they were almost like bedroom slippers,’ says Ratmansky. ‘The tiniest change of weight was visible…There was this lift,’ he remembers. ‘She wanted to catch a particular note in the music at a certain angle.’ They repeated it until it worked exactly the way she wanted.

The effort Ratmansky made to learn how to “catch a particular note” comes across in his style of footwork, which is often described as “clean.” Dancers under his direction continually describe the thrilling and elaborate physical effort it takes to keep up. “It’s almost as if someone had washed each step,” one dancer said.

As the years went by, and Ratmansky’s ballet repertoire grew, so did his curiosity and reverence for the history of ballet. At one point, he learned how to read cryptic 19th-century ballet notation, called the Stepanov system. He recreated lost scenes and whole ballets based on his interpretation of those original notes. He takes on “the work of the restorer,” Harss writes. He interprets archival material that is only partial. The reader witnesses Ratmansky’s slow revelation of his place in the ballet canon. He comes to see how much his interpretation is now defining the ballet world around him.

A sense of private cherishing infuses Ratmansky’s creations.

At New York City Ballet, Ratmansky creates a final role for Wendy Whelan after she underwent a major hip surgery, a pas de deux that served as a parting gift before her retirement. “Embedded in the choreography are messages and memories,” Harss explains. “At one point, Whelan touched the stage, as she had in Russian Seasons, Ratmansky’s first ballet for City Ballet, their first collaboration. Later, she waved goodbye.” A sense of private cherishing infuses Ratmansky’s creations. Early in his career at the Bolshoi, he danced with the seventy-six-year-old star, Maya Plisetskaya. “In a film of the performance, Ratmansky touches her forearms with extreme delicacy,” Harss writes, “as if handling a national treasure, which she is.”

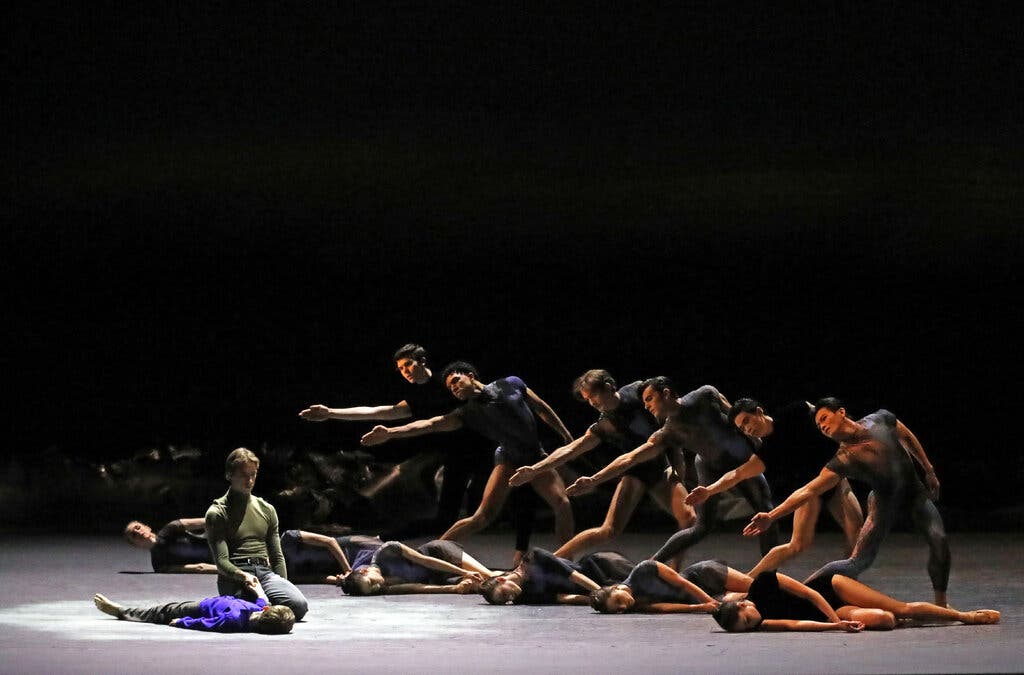

In February, months after The Boy from Kyiv was published, Ratmansky created his first ballet as artist-in-residence at City Ballet. The work was called “Solitude.” It emerged from a single photograph he saw of a Ukrainian father kneeling over the body of his 13-year-old son, killed by a Russian missile in Kharkiv. The cultural critic Sarah Sentilles studies the ethical implications of photography. “What should one do when faced with images of violence?” she asked in the wake of Abu Ghraib. Sentilles looks to the filmmaker Ariella Azoulay’s work. “It’s not empathy she’s after;” notes Sentilles, “she wants action.” For Azoulay, “Viewing a photograph becomes a kind of reanimation: the still photograph begins to move, and though this motion cannot erase inequality, it can trouble oppression that might otherwise seem intractable.”

In “Solitude,” Ratmansky’s longtime practice of catching a particular note transmutes itself. No longer is he designing dances around the amusing things that humans do with their freedom. Rather, he brings the whole history of ballet to bear on a single image of irrevocable loss from a world of atrocity. Some of his former Bolshoi classmates, even Ukrainian ones, have sided with Putin, an act of betrayal Ratmansky finds utterly abominable. His art has always been public-facing, and he’s made choices about what and whom he’s lifted up. Time and again, he’s highlighted intimate human exchanges before the alternate temptation of elevating an abstract national triumphalism. Whipped cream is all the more precious when you’ve been through the aftermath of Chernobyl. What seemed frivolous — a joke, a nuzzle — suddenly becomes potently worthy of protection.

Ratmansky continues his work as a restorer, but now his restoration involves holding shards of the shattered present.

“Solitude” represents a transformation, one that reveals the future beyond Harss’ book. Ratmansky continues his work as a restorer, but now his restoration involves holding shards of the shattered present. Taking in “Solitude” through the lens of Harss’ biography, painful, particular questions come to mind. Did the boy ever try whipped cream in a can? Did he love to walk under the blooming cherry trees in Kharkiv with his father? “Solitude” unfolds in portraits of inescapable grief, with no sense of resolution. In a recent reflection on the piece, Harss wrote:

As the man (in the second cast, danced by Adrian Danchig-Waring) kneels next to the prone body of his son (the eleven-year-old Felix Valedon), figures move around him. But he is not connected to them. It is as if he had become dissociated from the world around him.

At first the other dancers move toward him in a line, creating jagged, staccato images, like puppets in a dance of death… All this is done coldly, without expression. The figures are like broken fragments of reality, or perhaps something more inhuman, unfeeling spirits or external forces. The father and boy remain immobile. They exist in a different reality/dimension, separated from the others by a pool of light (lighting by Mark Stanley). The women line up nearby and fall, in angular waves, to the ground as the men take aim at them with open palms, revolve their arms once, and aim again. It is like a nightmare, an infernal machine.

Ratmansky treats the boy’s life with extreme delicacy, honoring him like a precious national treasure, which he is. Nothing can resolve the loss, but witnessing the specific moment is a form of reanimation, an act of defiance. Ratmansky, at the apex of his career, offers his power and the cumulation of his life’s work to honor the culture and people of his wartorn home country. He uses his imagination to pull a blanket of dignity over the boy’s body.

The Boy from Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet by Marina Harss. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023

Alice Courtright is a poet and writer living in New York. She thinks about literature, dance, grace, and the natural world. Alice has received degrees from Yale University, Sewanee’s School of Theology, and Yale Divinity School. She is ordained in the Episcopal Church, and her writing has recently appeared in The Hedgehog Review, Mockingbird, and SAGE Magazine. She lives with her husband, Drew, a parish priest, and their three daughters, about an hour north of the city. Read more at alicecourtright.com.

Categories: art, featured, literature, music