An Interview with Bi/etter Minds

Bi/etter minds is a collaboration between Minna Väisänen and Paul Hayes. Their comics and animations are beautifully stark and strange in a way that makes them seem almost like the only completely real thing — a sideways glimpse into the skewed framework that makes up our world and our interactions in it. Stemming from small, specific everyday human connections and disconnections but encompassing overarching human emotions — loneliness, sorrow, grief, greed, aging — Paul and Minna share with us their examination of the absurdity of being human. We were glad for the opportunity to ask them a few questions about their work.

Magpies: We live in such a noisy world in which “content” is more important than substance. Everyone is struggling to stand out to the point where it feels like an act of rebellion, almost, to not want anyone to see your work. And yet we don’t create art in a void. What is your idea about sharing work – who do you want to reach?

Paul: I can’t speak for Minna, I don’t know, but I think she does want to reach people. Personally, I really don’t give a fuck who sees it. I am the audience. As long as I get it, enjoy making it and am proud of it. I really don’t care what others think.

Listen, it’s a whole accident that this started. It dates back to a comic Minna made about me visiting Helsinki to see Ride. I wasn’t that fussed, so I let her write what she wanted and it went on Facebook. I was just an unknowing model for that.

But we always slag off people or riff on issues. One issue was parents on social media and working with technology at home influencing children. That became When I Grow Up.

Minna wanted to make images for the things I had heard children say. She did. I pointed out when the children should look younger, sadder, more confused. It became a collaboration. I think we did the same for the next “talking head” comics like Twilight Zoned.

Minna wanted to put them online and I don’t have anything other than Instagram, so that format determined the look.

But I wasn’t interested in reaching people. I just do this for myself.

In a similar vein, the older I get, the less worried I feel about fitting in, going out, finding a scene, knowing what others are doing, any of that. Do you think that a certain maturity changes the way you feel about creating and sharing art?

Paul: I remember reading … Durkheim? Anyway, it was a structural sociologist going on about people “giving up” “losing ambition” “going through the motions of living.” But fuck that. Do we need a fucking purpose?

Yet. I never lost my ambition to make something good. But I realise I don’t have the personality that drives action forward. But I know I contribute significantly. These days I want to make a Miyawaki forest or create a garden like Piet Oudolf but using native Finnish flowers, shrubs, trees. I’m totally immature but I know I am. A little self reflection. A desire to leave the world a better place.

In what sense do you see your work as having a “message” or messages that you want to share with people on a political level or otherwise?

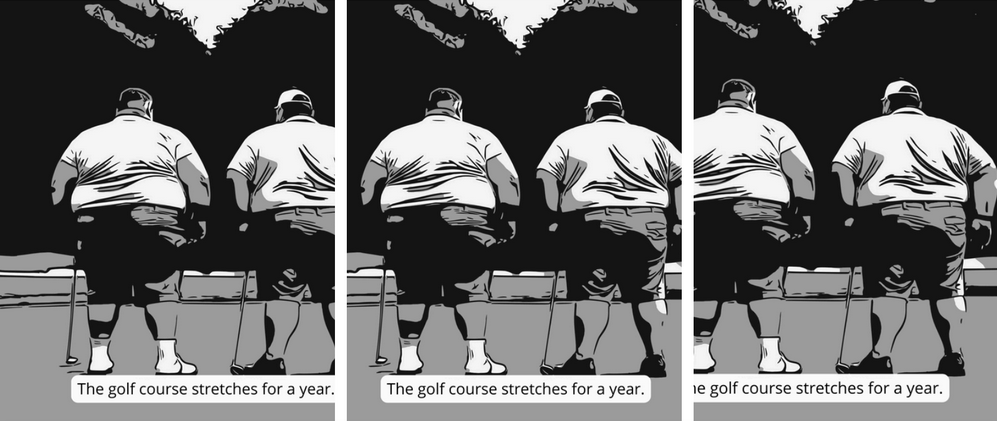

Paul: The Year Long Golf Course is pretty fucking clear. Gardens and green areas to demonstrate wealth, influence and political power. It’s saying there are rich people out there who will use us as fertilizer. Ascension Day acknowledges that amoral people who like their work and its pay cheque will facilitate the dreams of psychopaths. Other times, there’s no message. We just write about everyday conflicts, bring to light human disconnections and connections.

At the moment, AI feels like a gigantic question, whether you consider it full of promise of full of threat or some mixture of both, it’s a complicated subject about which everyone has strong opinions. On the one hand maybe it offers more resources to more people, but it’s also, maybe by definition, soulless. And there’s a pervading feeling that it was created by evil people. What are your ideas about the advantages and disadvantages of using AI, and how does it feature in your work?

Paul: I really do worry about AI. Its use of natural resources is hideous. That pains me. I do think about quitting because of that.

I liken our work to being in a synth-pop duo in the 1970s or 80s. We’re a distinct subgenre in art and we won’t affect the mainstream (and AI art will have subgenres of its own in the future).

But we put heart and emotion into what we do and we are not fucking derivative. We’ve been banned or unable to enter a few events because we use a lot of AI. Yet these fuckers allowed in copycat art made by hand. Just derivative anime and manga. Shite fantasy stories about super powers. Such utter wank. And then they set some of it to music that used computer programmed beats and synths to emulate orchestras. Fucking hypocrites. Don’t touch my industry! (But let me abuse yours.)

At least our style is our own. I’m not saying we’re Tomine, Drnaso, Maguire, Clowes but I love what we do and we are honest and upfront about our work.

As for the soul … We put real emotions in there. Try to show what we can about what is in our hearts. Who else writes about wailing autistic girls and distressed dads on public transport?

We’re not using AI to copy. We’re using it to tell our stories. To be honest, I don’t like much computer art.

I love it when I see a canvas and brush strokes, emotions poured out and rendered physically. But I’ve seen plenty of art that’s just an idea rendered without emotion or work that feels phoned in to fill a gallery space. We won’t be doing that because we don’t need to. We have rich lives beyond our art.

At the same time, AI isn’t the only technology that’s coming along apace. I like to think about movements like the French New Wave, when irreverent rebels took advantage of cheaper and lighter equipment to lay bare the conventions and means of production that had formed such a stodgy and stifling film industry. Do you see the potential for digital photography/phone photography and video, which is so much more accessible to everyone, to have this same revolutionary impact? Or is it too late?

Paul: The French New Wave was so bloody good because they knew the conventions, had studied and loved cinema, were visually literate in many aspects of art and life. Are people today aware of art history? Sometimes I feel that the current generation is being shortchanged in the lack of art teaching. Yet it’s all available online. We have to encourage curiosity and creativity. We have to say it’s okay to fail when being creative and accept that our shit stinks.

Anyway, we’re not part of any new wave. But we see the potential in the technology to tell our stories as we want. I’m 60. Who will tell my stories of everyday life? Will Wes Anderson do it? I fucking doubt it. But people can. But few do it beautifully.

Sally Wainwright is doing it with Riot Women but even her work uses a police procedural to tell stories as Gen X becomes the new pensioners. The potential for grumpy old gits like Bi/etterminds to use the technology is immense. But to make truly great art … Maybe people can. But then getting people to see it and having them immerse themselves in the stories … No idea But I hope others try to do what we are doing. Explore the potential. Let your old self shed a skin and grow.

I’m fascinated by your collaborative process, in which it seems that the act of creation starts with the sharing of ideas and memories, with inspiration and conversation. Can you talk a little about how you work together to create your comics and animations?

Paul: We wrote an article called Animated Rhythms to explain our process. That’s a good source. But let’s return to how we started … We chat shit about people and issues. After a while the chatted shit becomes prime fertilizer and we take the seeds we find in the words and grow something. That becomes its own ecosystem from unseen soil microbes to flowers, fungi and a beautiful tree canopy.

Basically, we use WhatsApp to send ideas back and forth once we have a good idea. We match words to image, image to words.

I’m not very involved in the animations. I do stomp my feet and protest if something is badly wrong and I make annoying comments about film rhythm, editing and sound. But as long as it’s unique and I like it, I don’t usually stop what Minna does with the animation. That’s her realm.

Listen, this is a hobby. I’m a local council gardener, shaping the urban landscape (it’s often art as well). It is very definitely physical work that leaves me exhausted. I also have three children. I like my sports and other hobbies. I’ve suffered mental health breakdowns. Bi/etterminds allows me to express core parts of myself but I also have to live my regular life otherwise I burn out. At the moment, it is a lovely balance. Family, work, art but doing the actual animation requires energy and time I don’t have.

On that note, I was very struck by the balance between personal and universal in the comics and animations. Some of the stories felt very specific to a particular experience, but they also spoke to broader human emotions of grief, loneliness, alienation, and the general confusion of modern life.

Paul: I’m so happy you found those broader human emotions. Apart from the obviously sci-fi genre comics. Everything came out of real-life interaction. But even the sci-fi is based on what some politically powerful and extremely rich are attempting to do.

There’s quite a dark edge to most of your work, with a lot of angry energy and a feeling of desperate loneliness. Is your view of the world as bleak as it seems or is art a way to express these feelings or to connect and commiserate with others who may feel the same way?

Paul: Yes. My view of the world is bleak. I made a crap short film 30 years ago about what people now call “the manosphere.” In the unmade full version the protagonist used social media (video diaries) and satellite TV to reach his audience as he became a populist cult hero. I could take that script and people would think I wrote it yesterday cos effectively fuck all has changed.

I had hoped the slightly more culturally open societies of the late 90s and early 00s would bring positive change but the rampant inequality and capitalism of that era and lack of social and political movements acting in a unified manner for even the incremental betterment of all was a catastrophe.

Yes. I’m bleak and angry but I’ve always had that dark edge. And yet here I am planting trees and flowers, weeding, trying to talk people out of cutting down trees. Trying to show the benefits and beauty of native plants, making our world a little more beautiful and bearable.

I want to show love for the world but that sometimes means you have to be honest and confront its ugliness first.

What is your grand ambition? Are you interested in exploring narrative structure in longer-format films? This might circle back to the first question, but what is your ideal audience?

My grand ambition is to write and make a full-length feature film using the apps we always have. But it has to be in the style we have developed.

I have a very simple but sentimental idea, which I know is achievable. Minna will give it a rawer tone. But the idea is so commercial and universal. We’d need time away from our jobs to do that.

But we are always writing and developing ideas in our subconscious. You never stop. The difference is I rarely showed my work before.

Our ideal audience gets the little jokes, like AI saving the world but animating a human with six fingers. Maybe they recognise what we do. I have mates who don’t get it and a few who are amazed and love what we do. I love them equally.

The Waiting Game

Quiet Lives, ignored talent, recognition on pause

Minna: I grew up in the countryside, far from my siblings, with only books, my dog and cat, parents and my imagination for company. Those long stretches of solitude taught me to be with myself, to observe, to imagine, and to create my own inner world.

When I got to university in Turku in the early ’90s, it felt like a relief, a fresh start. That’s also where I met my soul-mate, Paul, 35 years ago. He brought British youth culture into my life—mags, clothes, music, and, oddly, feminism.

After my B.A., I moved to Helsinki for film school, but the competitive environment—gatekeepers, bullies, the usual art-school elbows—was too much. I didn’t make friends there. Or a career on film-industry.

Later, I found refuge in IT, where solitude with computers felt safe and predictable. For the last 20 years, I’ve worked at a media school in Helsinki, first as a Head of Department and now as a teacher, with a superpower for spotting talent among the silent ones.

The process includes writing, shooting or prompting seed photographs for animation, vectorization, editing and sound design. Distribution and publication cover Vimeo, Instagram, and the project’s WordPress website. I also handle poster design, FilmFreeway submissions, article writing, and publicity.

About Directing

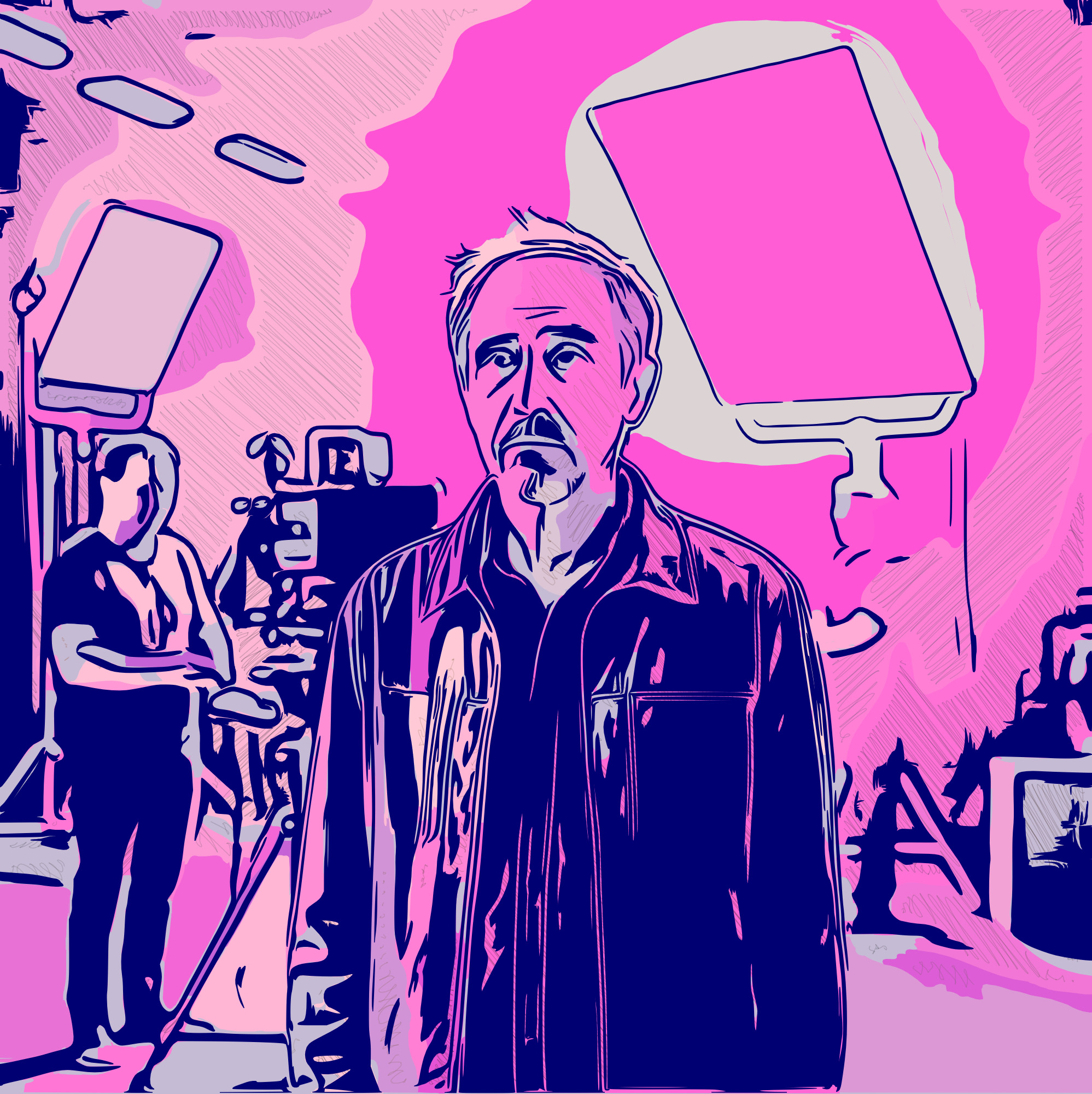

In the real world, actors have something solid to grab onto. They live in it, breathe it, carry it in their bones. A glance, a word, a gesture—they pull from life itself. Three, maybe five takes, and it’s done. After that, it rarely gets better. Reality is a scaffold they already stand on.

Animated characters don’t have that luxury. They start as algorithmic chaos. They try to read my prompts, guess what I want, translate instructions into something like emotion. Fifteen retakes, sometimes more, before a shot even breathes. And the emotions are mine—pulled from real stories, reflected back through something that doesn’t know what it’s feeling.

Prompting a character is like working with a stubborn student. He doesn’t get it, doesn’t want to, wants to do his own thing, something he saw online. By day’s end—vectorizing, prompting, tweaking, editing—when I see an IG post saying “Kill AI artists,” I don’t know what to hate first: my ambition, the character, the comment, my apps.

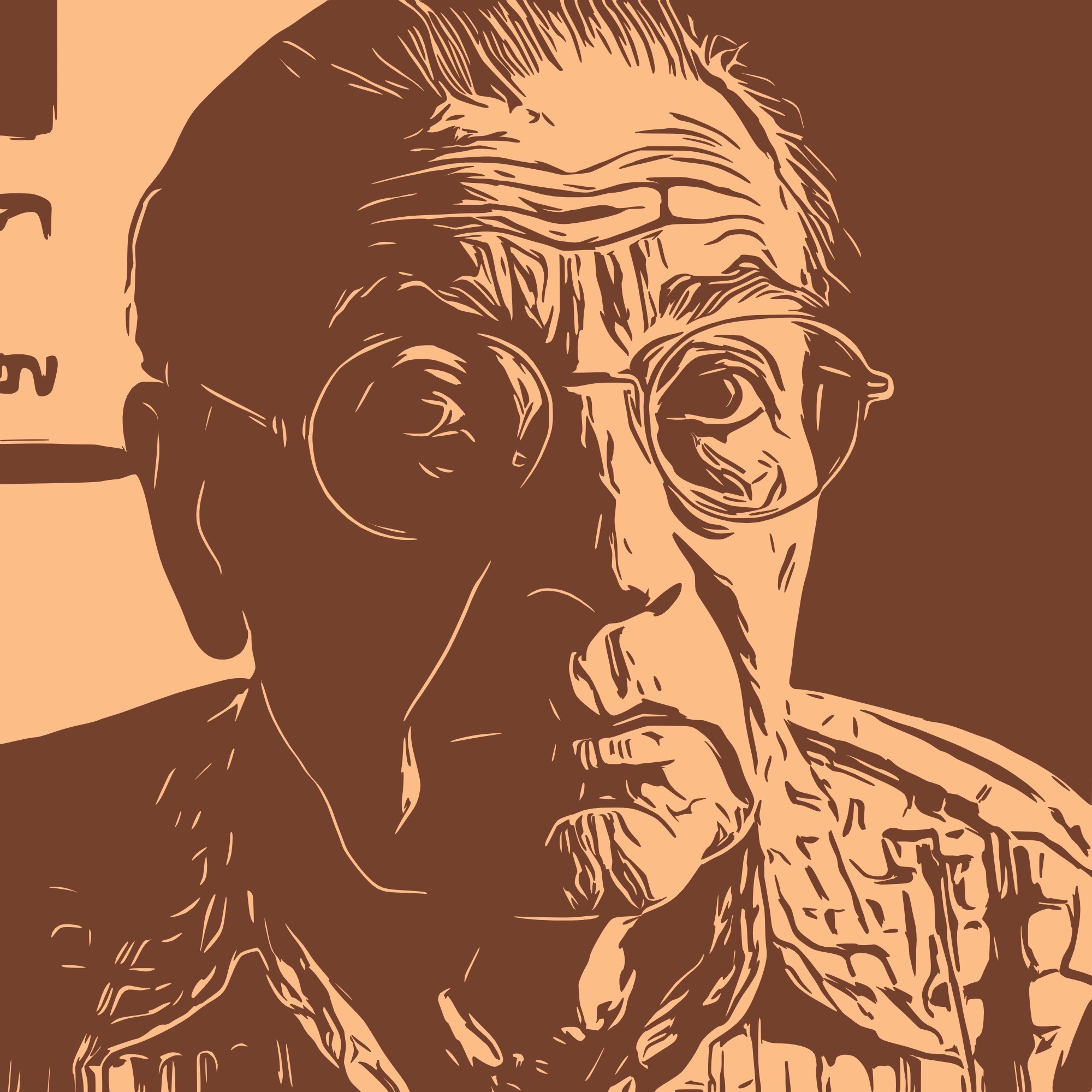

Working on Pensioned Off, with its old, cranky, obstinate characters, I remember the joy when the algorithm finally got it. The fragile old lady, the cranky old man, the despair, the fake teeth, the odd gestures—they all came alive, imperfect but full of character. And yet, despite all the chaos, suddenly it works. Every invisible argument, every micro-adjustment, becomes something human on screen—a reflection of what I want the audience to feel.

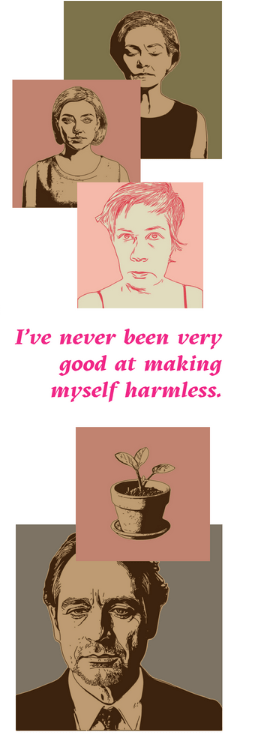

The Guerrilla Girls’ The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist from 1988 still really resonates with me. They pointed out how women are often overlooked, with careers that sometimes only “start” when you’re eighty—or even after you’re dead.

Women are assumed less serious, less capable, and expected to justify ambition. Their work highlights the absurdity: you can produce work, but visibility often comes late—or not at all. Nowadays, I know it’s not just women—it’s those lonely boys too, the ones who grow up isolated, figuring out the world on their own. Recognition is delayed for anyone outside the expected social molds.

All of these experiences—childhood solitude, struggling at university and film school, years of quiet work, and finally creating on my own terms—have shaped how I see life and the work I make.

Maturity strips away the fantasy that art is going to rescue you, validate you, or finally make you acceptable. When you’re younger, creating is often tangled up with being seen, approved of, or forgiven. With time, that urgency burns off.

You’ve already survived being misunderstood, ignored, or quietly sidelined, so the threat loses its power. That makes the work calmer and sharper at the same time.

Maturity also makes you less willing to explain yourself. You trust the work to do its own talking, and you accept that it won’t speak to everyone. That’s not bitterness, it’s precision. You stop aiming wide and start aiming true.

On a more personal level, the work is also about dignity. About whose inner life is considered worth depicting and whose is treated as background noise. If that unsettles viewers or makes them feel implicated rather than reassured, that’s intentional.

The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist

- You get to be “discovered” at 70, which saves decades of disappointment.

- Your work is always “personal, ” “emotional, ” or “intuitive, ” never just good.

- You can work for exposure forever. Museums love that.

- If you succeed, you’re an exception. If you fail, it’s proof.

- Your career gaps are explained by biology, not by gatekeeping.

- You make less money, which keeps you pure and uncorrupted by capitalism. Apparently.

- You’re praised for resilience instead of paid for skill.

- You can be ignored without anyone calling it censorship.

- You get panel invites to talk about being a woman, not about your work.

- Your anger is “interesting, ” until it becomes inconvenient.

- You’re told the system has changed, right before it proves it hasn’t.

- You inspire young girls, which is a touching substitute for institutional power.

- You don’t have to worry about being overrated. Ever.

The interest in FX sounds comes directly from the world of silent animation itself. Essentially, you have to build all the layers: room tone, atmosphere, foley, spot sounds, dialogue, voice-over. A “proper” animation can easily have over a hundred tracks stacked on top of each other.

The world is essentially created by layering these elements into a full soundscape. When you mute or swap sounds, the effect can be striking. If you “mute” the atmosphere and leave only specific sounds—like breathing or flying—it transforms the reality, creating an entirely new perception of the scene.

My ears pick up sounds from the environment, and my brain amplifies them. I can go crazy when someone chews gum on the train and I have nowhere to escape. I try to avoid using noise-canceling earphones and train my brain not to react to everything—like sleeping with a ticking clock. But I think living in this kind of sound world comes through in the animations I create.

Sound is not written as sound in the screenplay, but it is implied through action, rhythm, and image. Pace, repetition, absence of dialogue, small physical actions, cuts that feel abrupt or lingering. All of that tells you what kind of sonic world the film wants.

Often, that means exaggerating certain textures and suppressing others, building a subjective soundscape rather than a realistic one.

The Hidden Hands of Animation Sweatshops

AI makes visible the labor, bias, and gatekeeping animation has long hidden.

A lot of industrial animation has always been repetitive labor, often outsourced to lower-paid workers in so-called third-world countries.

Seen in that context, the advantage of AI is obvious. It compresses time, handles repetition, and takes on the kind of mechanical work that has long been invisible and undervalued. It can surface patterns, assist with structure, and free human attention for decisions that actually require judgment and experience.

Used well, AI also lowers thresholds. It opens doors for people without institutional backing, large teams, or endless resources, and removes some of the gatekeeping that has never had much to do with artistic quality in the first place. The technology isn’t a rupture so much as a continuation, just one that finally makes the machinery visible.

Also, Bi/etterminds look is not the recognizable AI aesthetic with its sleek, high-definition polish. It’s grounded in an Eastern European visual tradition, one that values texture, imperfection, and a certain roughness of feeling. The images are allowed to carry weight, history, and friction instead of aiming for surface-level smoothness.

That grounding is important to us. It resists the idea that new tools automatically demand a new, glossy language. AI may assist in parts of the process, but it doesn’t dictate the sensibility. The work still draws from older visual cultures where restraint, ambiguity, and unease are features, not flaws.

In that sense, the technology is deliberately kept in the background. What comes forward is a human lineage of image- making, shaped by limitation rather than abundance, and by experience rather than Optimization.

AI-con artist ?

Being honest about using AI as a tool often puts us in the position of being labeled or shamed as “AI artists. ” We respond to that by being transparent and factual. We name the tools we use and specify which of them are AI- enhanced. In reality, that list includes most contemporary digital animation tools.

My comic, “Peephole to the Past,” was based on my vectorised holiday photographs. It was banned from a competition for the use of AI despite the source material being my own images.

People often don’t realize that a “pure” digital line is never purely manual. A clean line drawn on a Wacom tablet is already mediated by algorithms. The brush predicts movement, corrects jitter, smooths curves, and compensates for human inconsistency. That assistance has been normalized for years, just not labeled as AI.

And for the record, this isn’t a substitute for skill. I can actually draw, and I’ve done my art classes. The tools don’t replace that foundation, they sit on top of it. AI doesn’t create the work.

Our very first comic, based on my vectorized holiday photos, was banned from a competition for “use of AI. ” It says a lot about the current atmosphere in the art scene. The judges had read the long article we wrote about copyright and AI, and drew their own conclusions—without asking us.

Nobody’s Child

Our second comic character in Vision was created using the website ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com. It was a huge relief to be able to generate an endless number of faces. Without this site, our comics and animations would probably all be about Paul.

No permissions, no release forms, no studio bookings, none of the hassle that comes with shooting real people. When I Grow Up was the third comic, simply because you could suddenly use children’s photos. They’re nobody’s child.

I still use Paul as a character, though, as a kind of signature of our work. One real, living person. And he still gets those urgent messages like: “Send me a pic of a man’s hand grabbing a pole. Five fingers! Are your fingers really that even?”

BI/ETTERMINDS is a collaborative comic and animation project by Minna Väisänen and Paul Hayes. Bi/etterminds uses text, image and animation to give voice to the observations and concerns of Gen Xers nearing retirement. Their work has been shown internationally, including in Toronto, Vienna and Bangalore.

Minna Väisänen is a visual artist, animator and writer. She blends personal memory, everyday tension and the quiet absurdities of human behaviour into her imaging.

Paul Hayes is a writer and editor. He shapes narrative, action and concepts.

All animations are available via our FilmFreeway profile. They are on Instagram @bietterminds.