Neal Rantoul, a remarkable photographer in his own right, shares a story of a transformative three days spent with Fred Sommer in the winter of 1979. He writes of the trip with a rare warm reverence for the photographer, the process, and the generous act of sharing knowledge.

By Neal Rantoul

I’d like to write about Fred Sommer in a more personal context in that he was hugely important to me in a stage of my career when I was looking for more clarity and understanding of my work and the work of others. By the late ’70s, six years out of graduate school, I was trying to figure out where I fit in the broader sphere of artistic expression in photography. Was I a “player”? Meaning, was I or could I make a contribution to the discipline that was significant? By this time, I was showing (Dartmouth College, Hampshire College, Addison Gallery of American Art, Tufts University, etc) and teaching (New England School of Photography and Harvard University), so there was some confirmation that I wasn’t a complete idiot. Plus, I was very passionate about making pictures. In fact, I worked all the time at it. But I had doubts too. I was shy, antisocial and felt inept in comparison to others who were climbing in their field faster than I was. I wanted success, meaning exhibitions in prestigious places, books, press coverage, and so on but wasn’t willing or able to step into the world where that was happening and people’s careers were being made. So I didn’t.

I wanted success, meaning exhibitions in prestigious places, books, press coverage, and so on but wasn’t willing or able to step into the world where that was happening and people’s careers were being made. So I didn’t.

So, I made work.

So, I made work. In 1978, I told New England School of Photography (NESOP) that I would not teach there anymore. My teaching at Harvard was only for the fall semester, so I took off in early 1979 on a cross-country road trip to shoot in the American Southwest. I would have left sooner but my aging Porsche 914 had rusted through a rear frame member the night before I was to leave. Getting this fixed took about three weeks. I left directly in late January from the dealership the morning I picked up the car and I was off. It was 9 degrees above zero out. Whoosh! I drove straight, heading south. VWs and Porsches were air-cooled in those days and so getting heat inside the cabin was marginal at best. I got to warmer places as fast as I could. After several days in New Orleans and Houston I eventually got out to Arizona and, through using mutual contacts with care and making phone calls and some small acquaintance with Fred Sommer from when I was in graduate school, arrived at his doorstep on the scheduled day and at the right time in Prescott, Arizona, on a Monday morning at 8 a.m.

Day 1

It was Albert Einstein’s birthday.

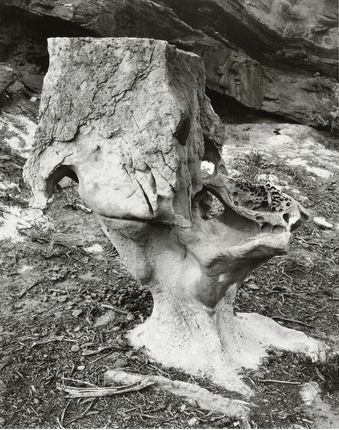

This turned out to be the primary conversation as we sat down to breakfast: Einstein’s contribution to science and our understanding of the universe. It was Fred, me, Fred’s live-in assistant and his wife Frances that morning. Fred, in 1979, was a senior and master photographer, rightfully acknowledged to be one of the discipline’s moving forces, a surrealist of the first magnitude who made black and white contact prints of unsurpassed quality from 8 x 10 negatives, among other things.

After breakfast, Fred suggested that the three of us move into the studio next door in his very modest home, while Frances cleaned up and headed off to work. The assistant, who had finished studying with Emmet Gowin at Princeton a couple of years before, sat down to my left in the corner of the room and brought out a notebook and pen with which to take notes. Fred took a daybed to my right and I was asked to sit in the middle in a comfortable chair facing the wall where many of Fred’s most famous works had been made. Behind me was a wall of small panes of glass. This to provide natural light for his still lifes.

Fred asked if I was comfortable and was there anything he could get me. Did I need to use the bathroom? He asked how my travels had been and was I having a good trip? I said that all was well and that I was having a very good trip, making many photographs, meeting some wonderful people but sorry it was almost over. He said that he thought that sounded excellent and that he was pleased to hear it was going well and hoped when I returned home soon that all was well where I lived, back in Cambridge.

As these pleasantries were now over Fred began to talk. In a soft voice, with occasional interruptions from the assistant or me, Fred talked all day. We did break for lunch, in which Fred prepared hamburgers on the stove in the small kitchen, which Frances had brought up from town specially prepared for us by the butcher at the market, to Fred’s specifications. For Fred, most things were ritualized, and cooking burgers was no exception. During lunch,h we spoke of other things, lighter things not so difficult to understand, as though this taking a break to feed ourselves was also a kind of recess from being back in there, in the studio. But after lunch, we were right back in there, in the same positions as before, playing the same roles: the assistant as the recorder who occasionally would ask for clarification on certain points, me as the clueless newcomer to Fred’s theories and use of the English language in a profoundly different manner from which I had understood it before arriving that morning.

Slowly, as the light left the day, Fred was talking from a void, as I could no longer see him, but just hear his voice as he sat on the daybed next to me. This was incredibly eerie and mysterious and moving to me.

As the afternoon wore on, we were getting to several key points; there had been enough introduction to concepts and enough defining of terms to be able to actually get to the many points Fred needed to make. In his careful, systematic way, Fred graciously took me through each one, always concerned that I have a full understanding before moving on to the next. At the same time, it being winter, the natural light studio was darkening as Fred continued to talk. Slowly, as the light left the day, Fred was talking from a void, as I could no longer see him, but just hear his voice as he sat on the daybed next to me. This was incredibly eerie and mysterious and moving to me. Eventually, he stopped for the day and then said that he hoped it had been a good day for me. I said that it had and thanked him. I, of course, assumed we were done. As I was getting my jacket on and preparing to leave to return to my motel in town for the night, Fred said that he felt we’d had a good start and that he looked forward to starting again tomorrow morning at 8 a.m. for breakfast. After a pause, I said that I too looked forward to our conversation tomorrow. Then I left with my head so full and having been so fundamentally altered by the events of the day I had dinner sitting at the bar of a restaurant not even tasting what I ate, drove back to my motel and went to bed, exhausted.

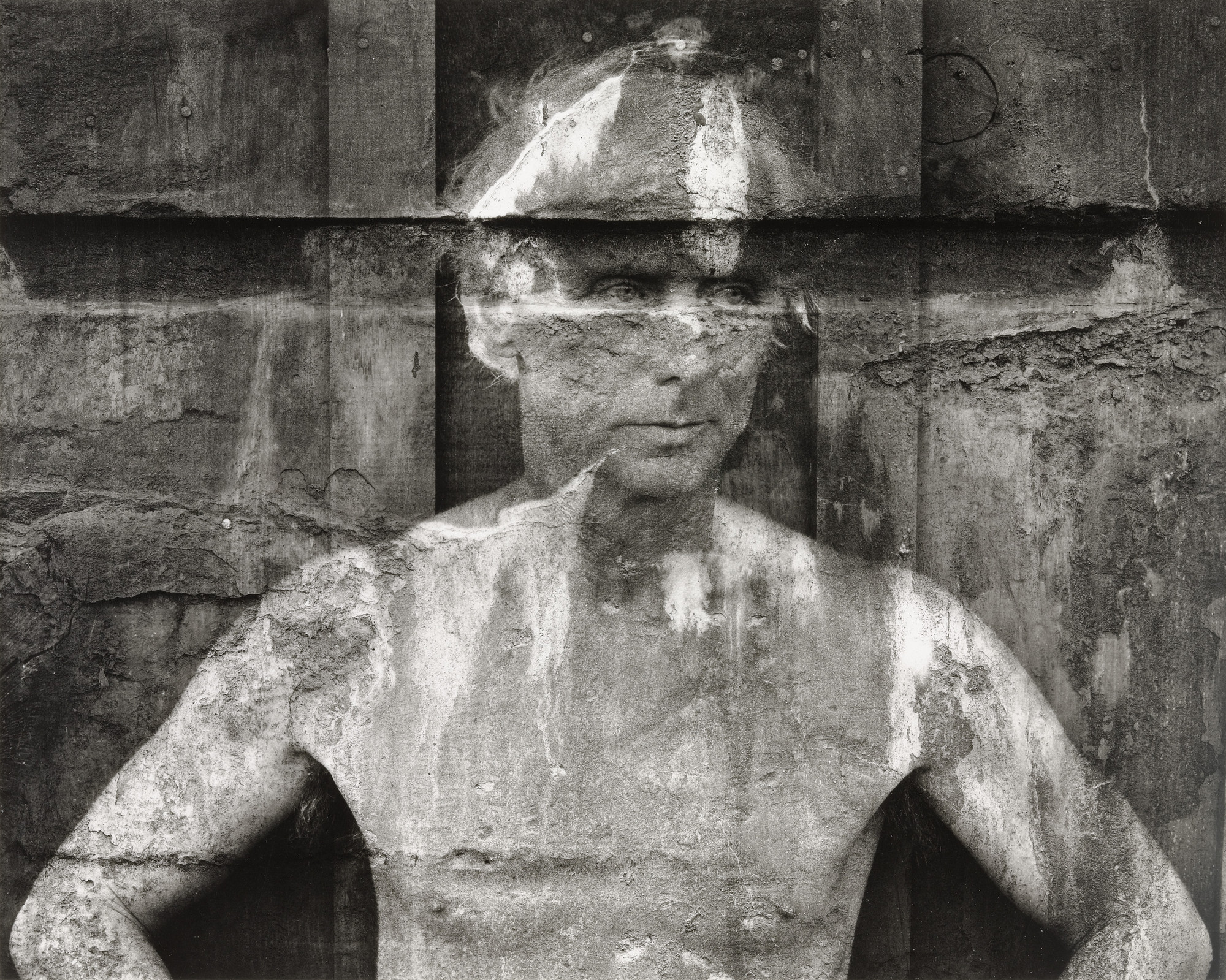

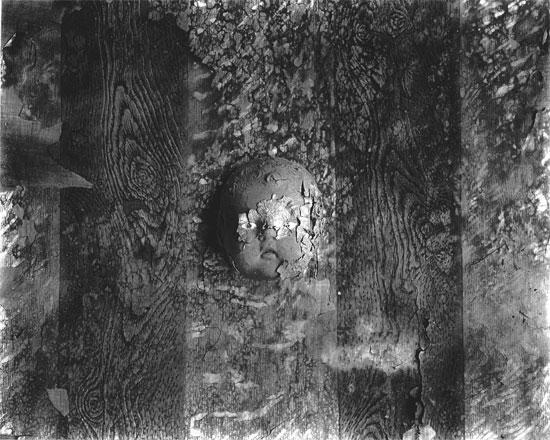

This is one of the pictures Fred made that involved no camera and used no negative.

Art is not arbitrary. A fine painting is not there by accident; it is not arrived at by chance. We are sensitive to tonalities.

Frederick Sommer

The smallest modification of tonality affects structure. Some things have to be rather large, but elegance is the presentation of things in their minimum dimensions

General Aesthetics, 1979

Day 2

Day 2 with Fred Sommer began much as Day 1 had, minus the emphasis at breakfast on the life of Albert Einstein.

I asked for some clarification on a few points and admitted that I was having some difficulty with the fact that he was using common words in the English language differently than was the convention.

After breakfast, we took up our respective positions in the studio, and Fred asked if there were any issues or questions I had about anything covered on the first day. I asked for some clarification on a few points and admitted that I was having some difficulty with the fact that he was using common words in the English language differently than was the convention. Fred would use them but they would mean different things. He found what I said amusing but offered that learning new definitions for terms was basic and important and that to be inflexible would inhibit further progress. Okay. I said that I understood.

And so we began the morning, this time advancing faster and with Fred stating his position with perhaps a little less restraint and perhaps a little more forcefully, as though he was no longer holding back as much for the neophyte in the room. I found the material extremely challenging but felt it inappropriate to interrupt Fred as much I had the day before. The assistant wrote a great deal the second day and also asked fewer questions as well.

But after lunch, there was an element to the presentation of Fred standing out on a ledge, somewhat precarious in that he was moving into new territory, either presenting ideas that were new to him too or at least presenting them in a new manner. This was tremendously exciting as I was there, a part of his working through theory and stating thoughts to me and the assistant for the first time.

Lunch came and went, much as it had the day before and I remember it occurred to me that it seemed I was having a somewhat choreographed experience, something if not “staged” then at least made before to others, perhaps in exactly the same configuration I found myself in, the assistant off to the left, me in the middle and Fred on the day bed to the right. But after lunch, there was an element to the presentation of Fred standing out on a ledge, somewhat precarious in that he was moving into new territory, either presenting ideas that were new to him too or at least presenting them in a new manner. This was tremendously exciting as I was there, a part of his working through theory and stating thoughts to me and the assistant for the first time. This incredibly brilliant and educated man was working it out right in front of me and I was hearing it. And so I thought that perhaps this was something of a two-way street, that I or someone like me was perhaps needed for all this to work. This was both an honor but also humbling simultaneously. Why? Because I could have been a crash test dummy for all it may have mattered.

Midway through the afternoon, Fred changed the pace considerably.

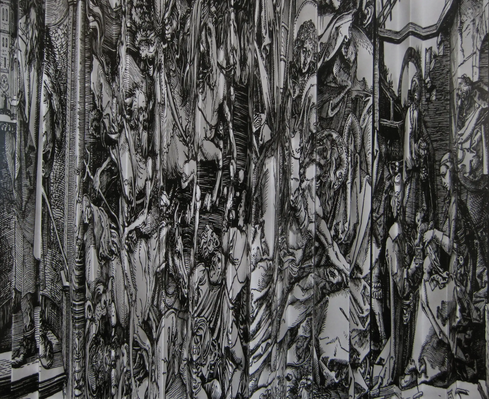

This then led us to a discussion and a showing of some of his musical scores, sheet music drawn by hand, with different colors for different instruments. I hadn’t known he was a musician and so I asked, and he said that he was not, but that a beautiful score would make beautiful music.

He asked if I was interested in music and if I was what did I listen to. I told him some of the standards which included symphonies by Beethoven and Bach and added the Mozart and Faure Requiems as well, also some Dvorak piano chamber pieces I’d heard at Marlboro the summer before, Stravinsky and Messiaen, as well as the Koln and Bremen concerts by the jazz pianist Keith Jarrett. He said he didn’t know those and I told him I had a cassette in the car that I would like to leave with him (which I later did). He thought that was a great idea and thanked me. This then led us to a discussion and a showing of some of his musical scores, sheet music drawn by hand, with different colors for different instruments. I hadn’t known he was a musician and so I asked, and he said that he was not, but that a beautiful score would make beautiful music. I asked him if his scores had ever been performed and he lit up and said that yes, they had. I wanted to know how they had sounded and typically Fred, he said that they were “beautiful to hear.”

Clearly now we were on a different level, things were no longer so presentational but more conversational, less as in a lecture and more now in a give-and-take. I didn’t know if we were finished but once again assumed that we would soon say our goodbyes and I would head back to my motel, exhausted once again and begin my long drive back east to home the next morning.

In fact I had grown up a little in those two days, with increased awareness of the complexity and the simplicity of things.

But evidently Fred wasn’t quite finished yet. He asked if I could return at 8 a.m. the next morning. I answered that I could and he said he was looking forward to seeing me. Then I left, not quite as done in by Day 2 as I was by Day 1 but still very tired and feeling a bit like I had let go of something of my previous life and given myself over to this new awareness and process of looking at things through the eyes and mind of Fred Sommer. In fact I had grown up a little in those two days, with increased awareness of the complexity and the simplicity of things.

Enthusiasm is the duty of understanding before the night fatal to remembrance.

Frederick Sommer

1962

Footnote to the musical scores: Many years after Fred died, the RISD Museum in Providence had some special events around the anniversary of his death (Fred died in 1999, with his wife Frances dying six months later). One of the activities was that they had a quartet playing Fred’s scores.

Day 3

I arrived at Fred’s door right on time on this third day of my visit. We sat down to breakfast just as we had the two days previously, then we moved to the studio and took our normal positions, Fred, the assistant and myself. Fred asked if there was anything he needed to review from our previous two days of work. I used this time to ask a few questions, which Fred disposed of quickly and efficiently but with extreme respect and courtesy as well.

This was different, I got a definite sense that things were drawing to a close and that there was much to do and it wasn’t going to get done with me hanging around. This man had spent two full days with me and put everything he did on hold for me. I said how very grateful I was and told him I would soon be on my way but did he mind telling me how he worked. He smiled as though the question was predictable but was warranted as well. He told me he made twelve photographs a year, with each one worked on for one month. In terms of the 8 x 10 work which included the landscape work and some of the still lifes shot in the studio where we were sitting, he and his assistant would make many prints, trying out different approaches and systems to get what he wanted from the negative. This included toners such as gold and selenium but also a method of acetate masking using color retouching dyes to selectively hold back tonalities so as to deemphasize some areas and accentuate others. He asked the assistant to bring out some prints of what they were working on then and he showed me how this system worked. I would later use this same system, although I was enlarging my 8 x 10 negatives and he was not.

Once we’d covered that topic it was clear it was time for me to go. I felt at a loss of words as to how to thank him. I rushed out to the car and got the Keith Jarrett cassettes and handed them to him. He thanked me and in saying my good byes to Frances, the assistant and to Fred, I became overwhelmed and was trying to hold back tears. I hugged Fred. This seemed to take him aback for a moment, then he relaxed and said that I was welcome. He wished me a safe journey home.

I got in the car, started it up and drove away with a wave. I remember I drove down to Prescott, which was smaller in those days and then as far as something called Granite Dells, which are wonderful rock formations to the east of town. There I pulled over and burst into tears, sobbing at the end of these three days of an intensely transforming experience and at the generosity of this man who had given me so much.

Once I pulled myself together and got back on the road the next thing I knew I was in Washington, DC, red-eyed, burnt out and exhausted after driving 2300 miles straight. My head was so full I thought it would break as I drove across the country in my aging yellow sports car with little heat. I crashed at a friend’s apartment that night and slept for a very long time.

Art is the oldest and richest inventory of man’s perception and comprehension of nature. It is the poetic image of what man has felt the universe to be and how he gradually became friends with different layers of materials and different layers of situations.

Frederick Sommer

Art and Aesthetics, 1982

No doubt, if you have read all three of these posts you feel cheated. I have described in detail the logistics and framework of my days with Fred Sommer but none of the substance. Were I to do so, it would do Fred’s words an injustice and deprive you of working through what he said and meant on your own. Much of what Fred spoke about to me is published, as he was generous with his thoughts and perceptions. I urge you to read what he wrote.

At the end of that most incredible of visits, I said goodbye to Fred and his wife Frances, got back in my aging Porsche 914 and drove straight from Arizona to Washington, DC and, effectively crashed. Staying with friends, if memory serves I slept for a night and a day, and then went out to photograph.

What I did was try to assimilate much of what Fred had told me earlier in the week.

If you’ve followed this blog for a while you know that it wasn’t until 1981 or 1982 that I came across the way of working I call “series work.” And yet, there I was making photographs that stylistically look much as the Nantucket pictures did three years later or the Yountville pictures did a little after that.

However, these are “immature” in that I knew nothing about linking my pictures together in 1979. I thought of these simply as single pictures reflecting the time and place and little else.

Neal Rantoul is a career artist and educator. He retired from 30 years as head of the Photo Program at Northeastern University in Boston in 2012. He taught at Harvard University for thirteen years as well. He now devotes his efforts full time to making new work and bringing earlier work to a national and international audience. See more of his work at nealrantoul.com.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, Nature, Photo Essay, photography