I have long been a huge fan of Calef Brown’s writing and art. Lines and phrases from his work are always in my head, recalled by the smallest thing to conjure up the worlds they are part of. Strange, wonderful worlds populated by remarkable animals and people and some beautiful mix of the two. Worlds that are oddly perfect and perfectly odd, strange in a way that seems just right — sincerely, almost necessarily strange — like all the best art and literature. I was beyond grateful to have a chance to ask him a few questions about his work.

What is your favorite word right now? What are some combinations of words that stick in your head? (Lyric, line of poetry, quote, nonsense).

Let’s see. Words.

I scanned a recent manuscript — one aimed at adults — and found some favorites: apropos, panache, gorgonzola, zephyr, prole, seraphim, nomenclature, sloop.

Looking back through my most recent book for kids – Up Verses Down, here are some favorite words there: gobbledygook, gumption, gewgaw, bandicoot, yurt, smidgen, kleptosomnambulist.

And some favorite rhyming combinations from the same book :

don’t antagonize / harmless dragonflies

entomology / ant apology

marsupial salad / his coupon was valid.

bric-a-brac / stickleback / pickle rack

rare occurrence / the air currents

mussel or an oyster / nestle in the moisture

a love sonnet / with doves on it

A favorite quote is one from the painter Philip Guston:

“You go in the studio and everyone is in there — your friends, and the art writers, and the museum people, they’re all in the studio. You’re just there painting. And one by one they leave, until you’re really alone. And then, that’s what painting is. You wait, and you prepare yourself. There’s nobody there, and then, ideally, you leave.”

When I think about your work I wonder what your imaginative world was like as a child. Did you have imaginary friends? Did you create worlds? Did you share them with anyone?

I did, however, love to envision entering particularly fascinating worlds that I encountered through reading, in a curious, active, participatory way.

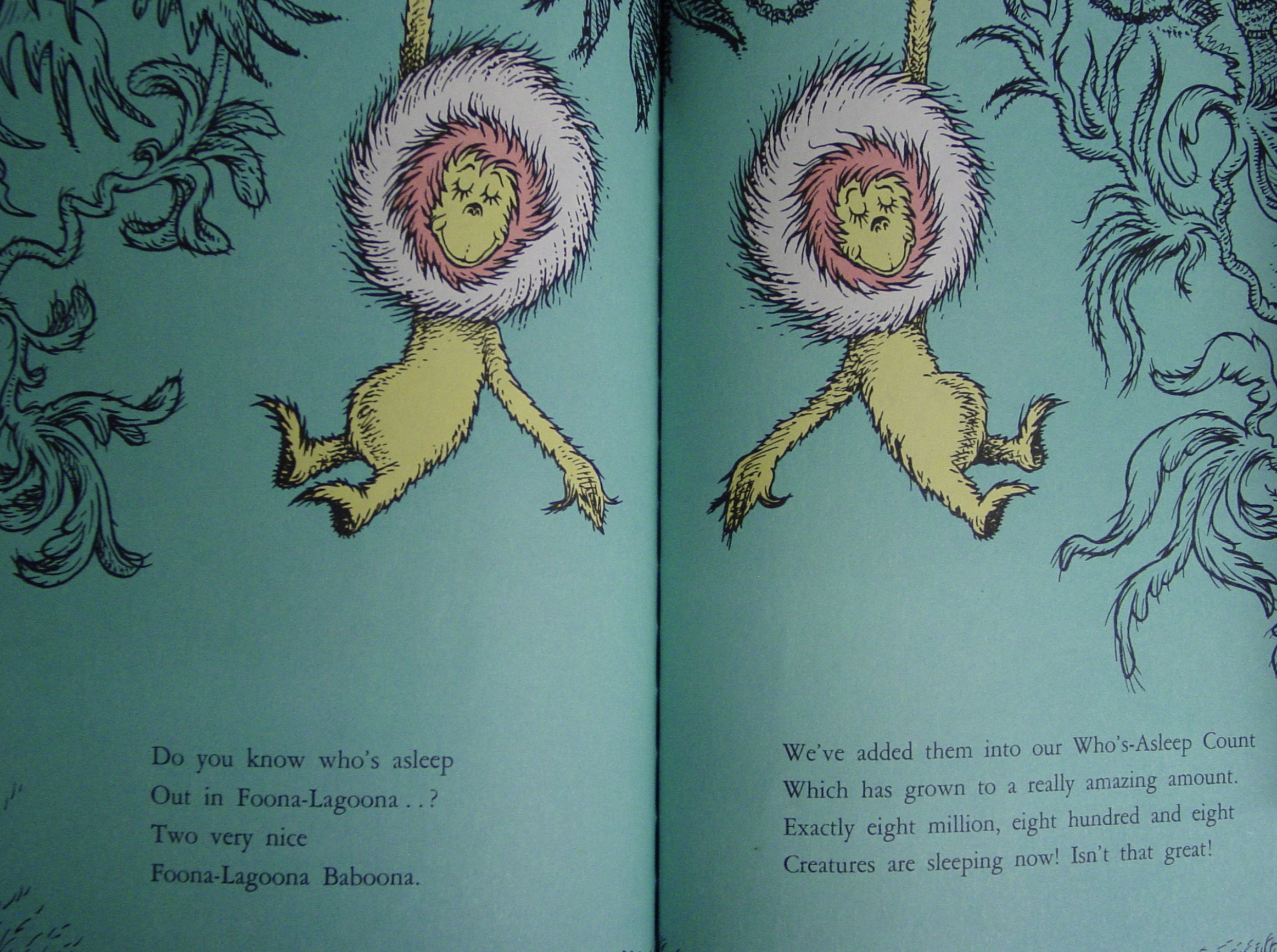

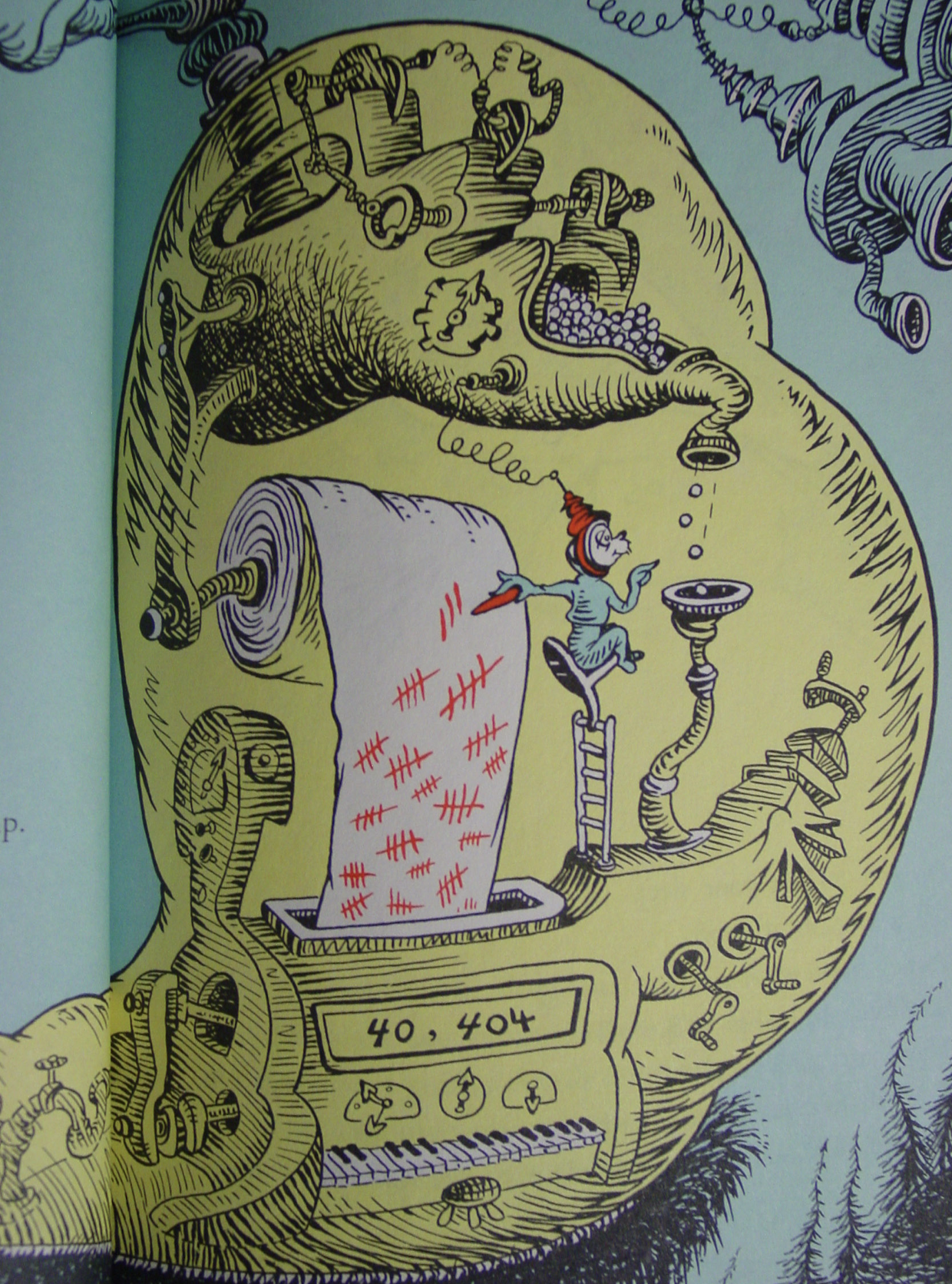

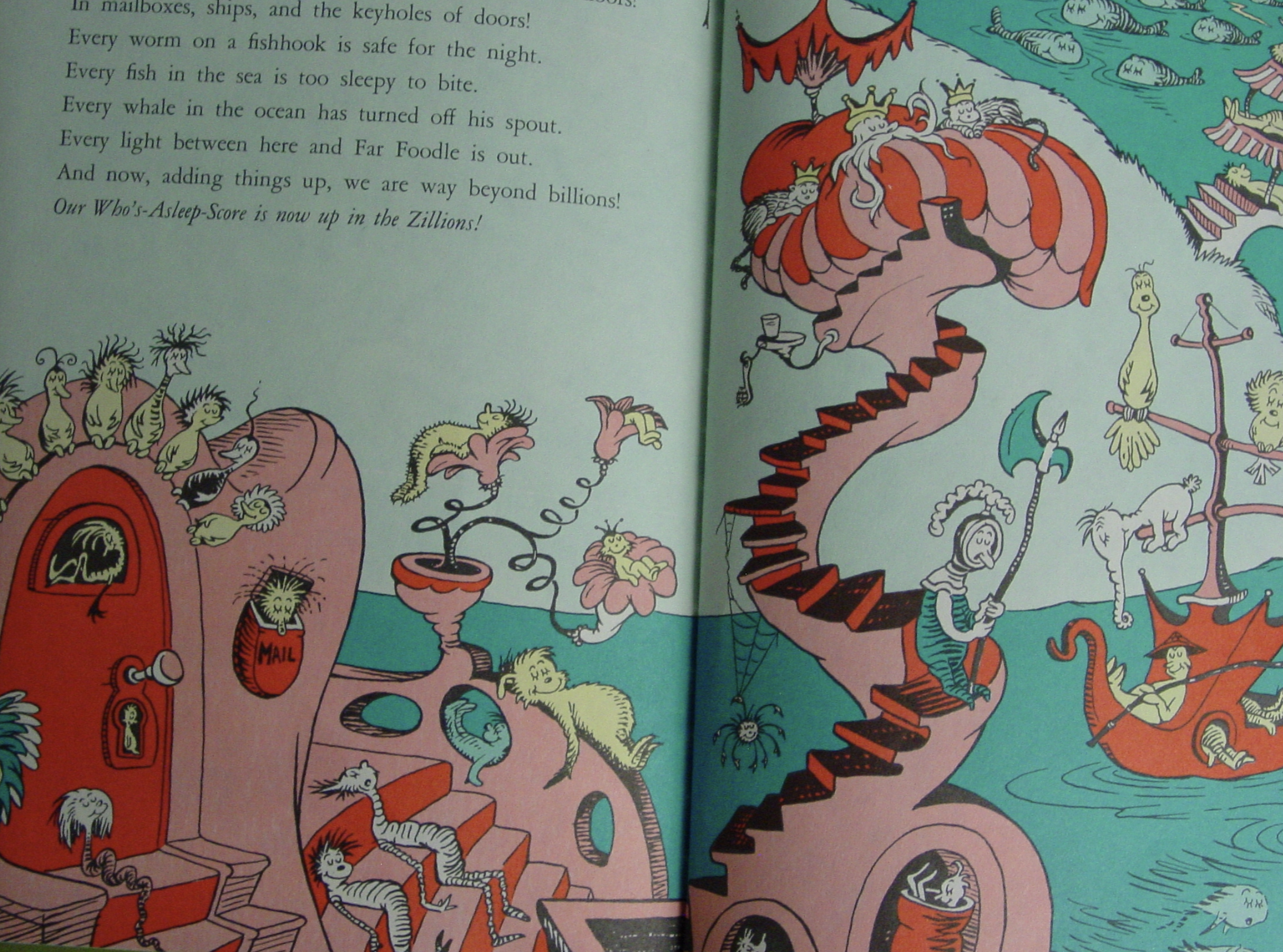

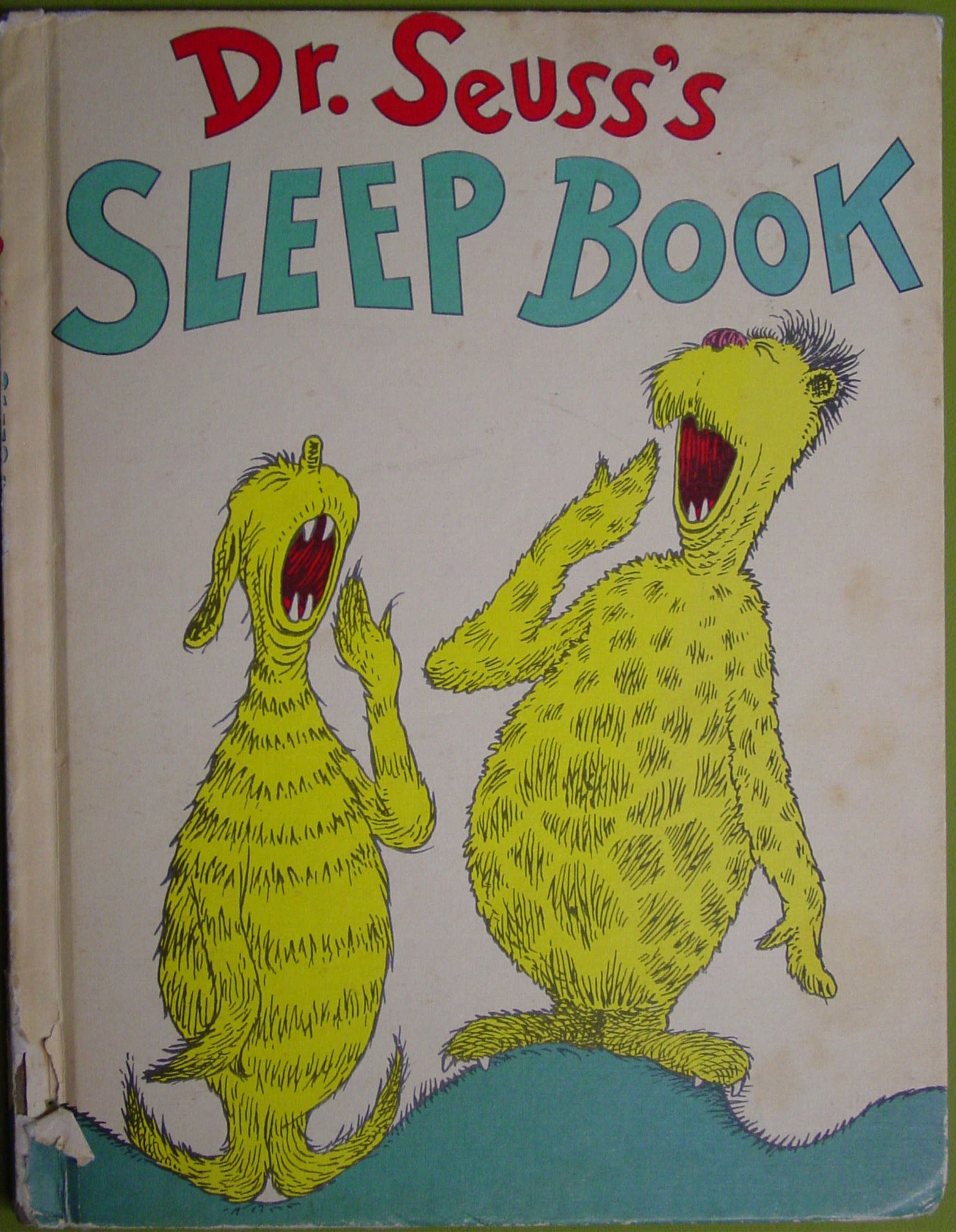

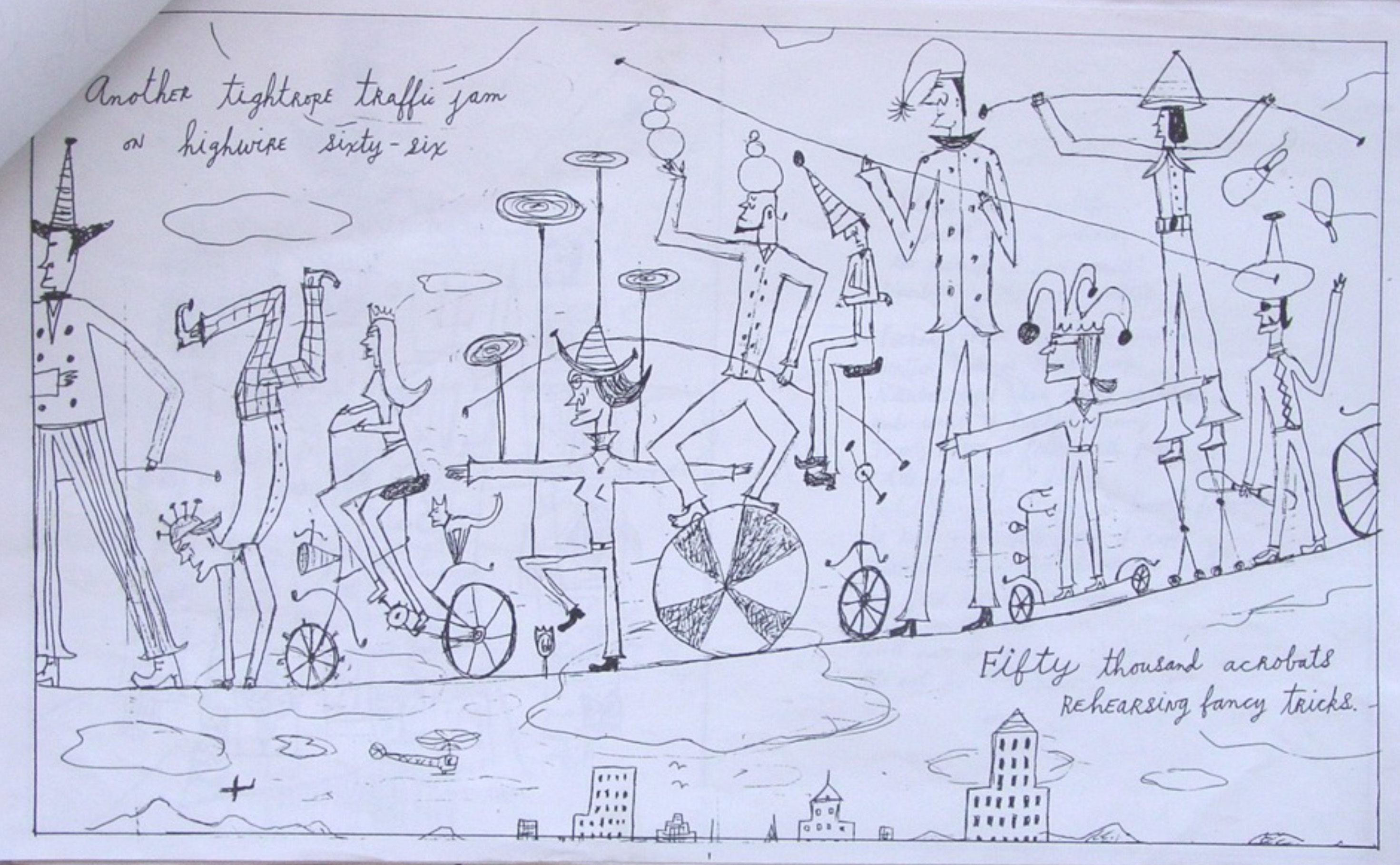

When I was a kid, I didn’t have my own personally invented imaginative world or worlds, really, or imaginary friends. I did, however, love to envision entering particularly fascinating worlds that I encountered through reading, in a curious, active, participatory way. A very ordinary kid thing. For instance, when I was about 6 or 7, my favorite book by a mile was Dr. Seuss’ The Sleep Book. I was enchanted, obsessed, really, by the convincing nature of this universe — consistent and fully believable within its own logic. Safe, loving, truly weird, and sometimes playfully scary. The place I would love to be. I wanted to inhabit that world — drive the crazy vehicles, live in the swirly houses, interact with the bizarre characters, the animal and plant life. And be free and independent there! It was quite unlike any other book I had seen, and I am glad I experienced it before reading Seuss’ more popular and less eclectic books ie: The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, Horton, etc., which I enjoyed later, but not in nearly the same way.

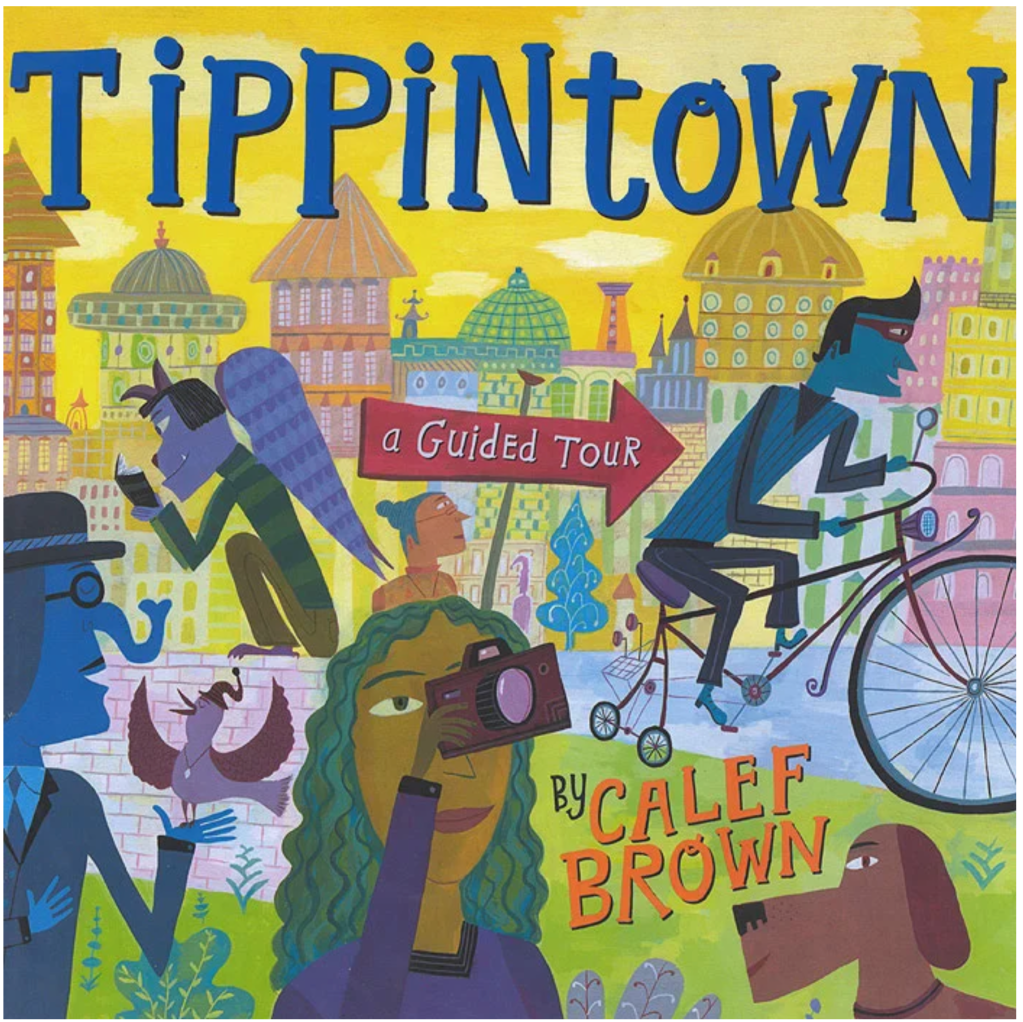

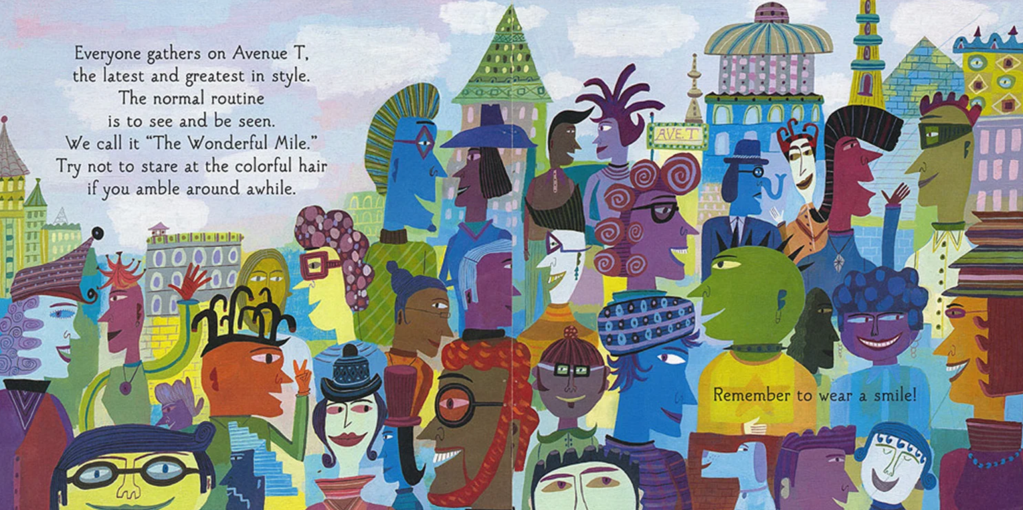

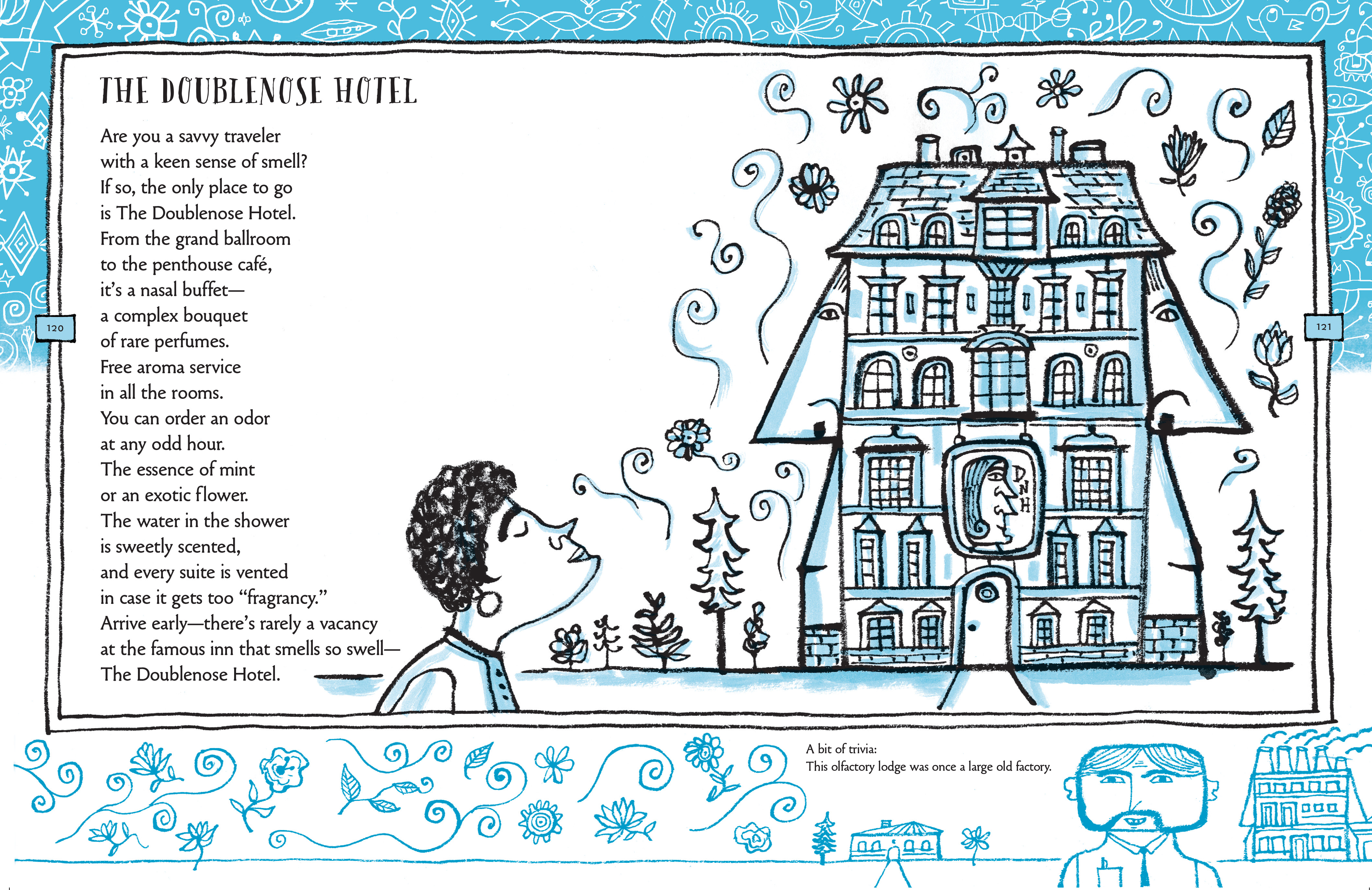

Of my own books, Tippintown — A Guided Tour, is most inspired by The Sleep Book, and that idea of creating a world (in this case a town) and taking you through its characters, places, and scenarios. Like The Sleep Book, Tippintown has an overarching theme, the narrative voice of the book is a guide showing us the people and sights, and each page spread pushes the story along, but also works as a stand-alone vignette — a riff on that theme, with rhyming text.

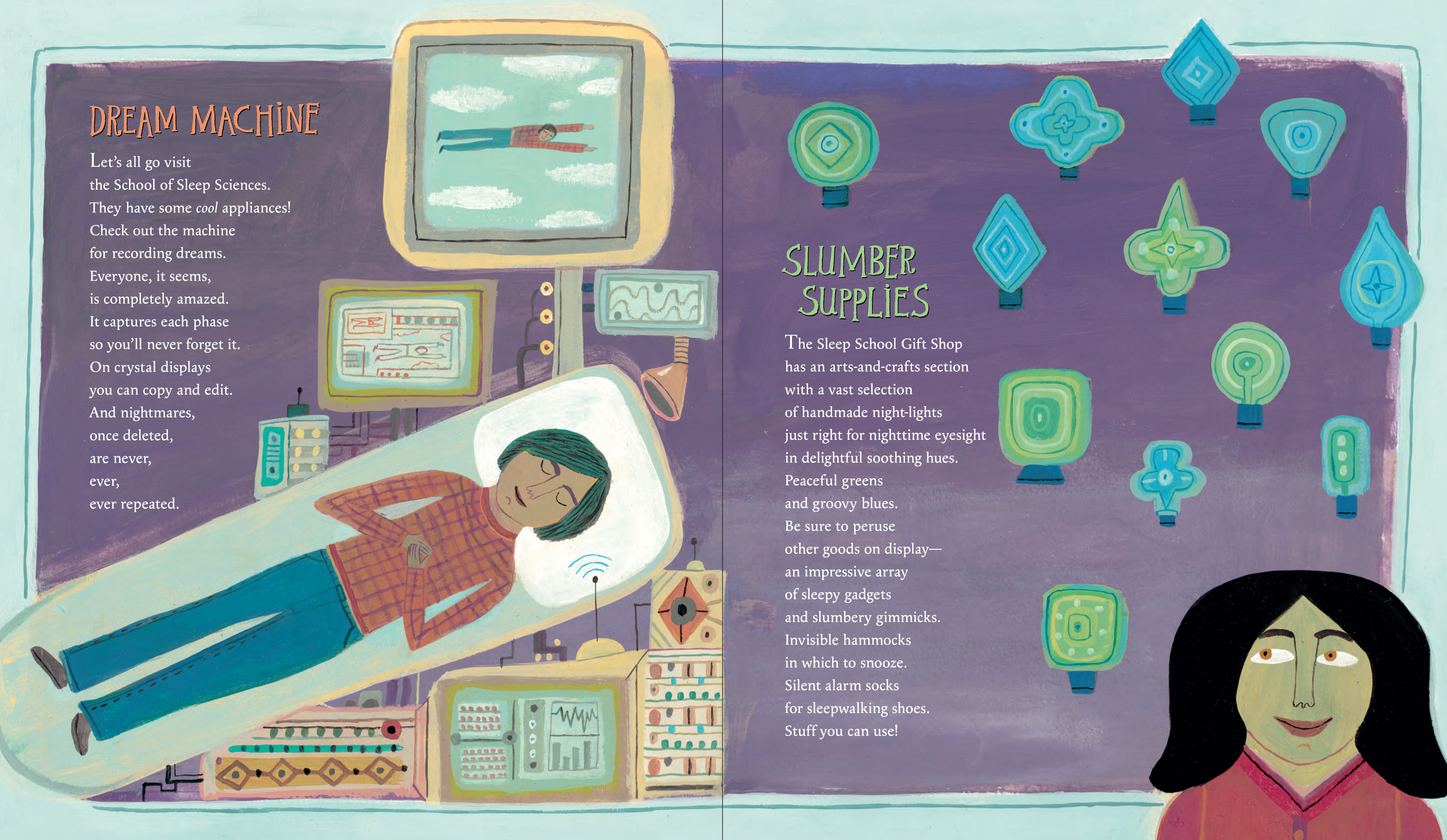

About ten years after Tippintown, I wrote a suite of poems on the theme of sleep, also inspired by The Sleep Book. There were not enough poems to make up a volume, but they later became a section of my most recent book Up Verses Down titled Sleepy Time. Here are a few samples:

Another example of a book-world that totally captivated me as a kid, around the same time, was Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. The stories, for sure, but mostly it was the vivid illustrations by John Tenniel. Another complete and detailed vision of a universe that hooked me. The presence and three-dimensional solidity of his characters, with degrees of exaggeration and distortion calibrated perfectly to fit their personalities. Another fantastic space that felt like it could be stepped right into and experienced. It was also somewhat scary, but in just the right amount. The faces of the characters especially got me.

Charles Addams’ cartoons were another example of this, a complete vision of his world, or version of this one, and the masterful velvety quality of his ink washes, whether foggy grey skies or interior spaces, they were so compelling to me. As if this gloomily charming place was made of ink.

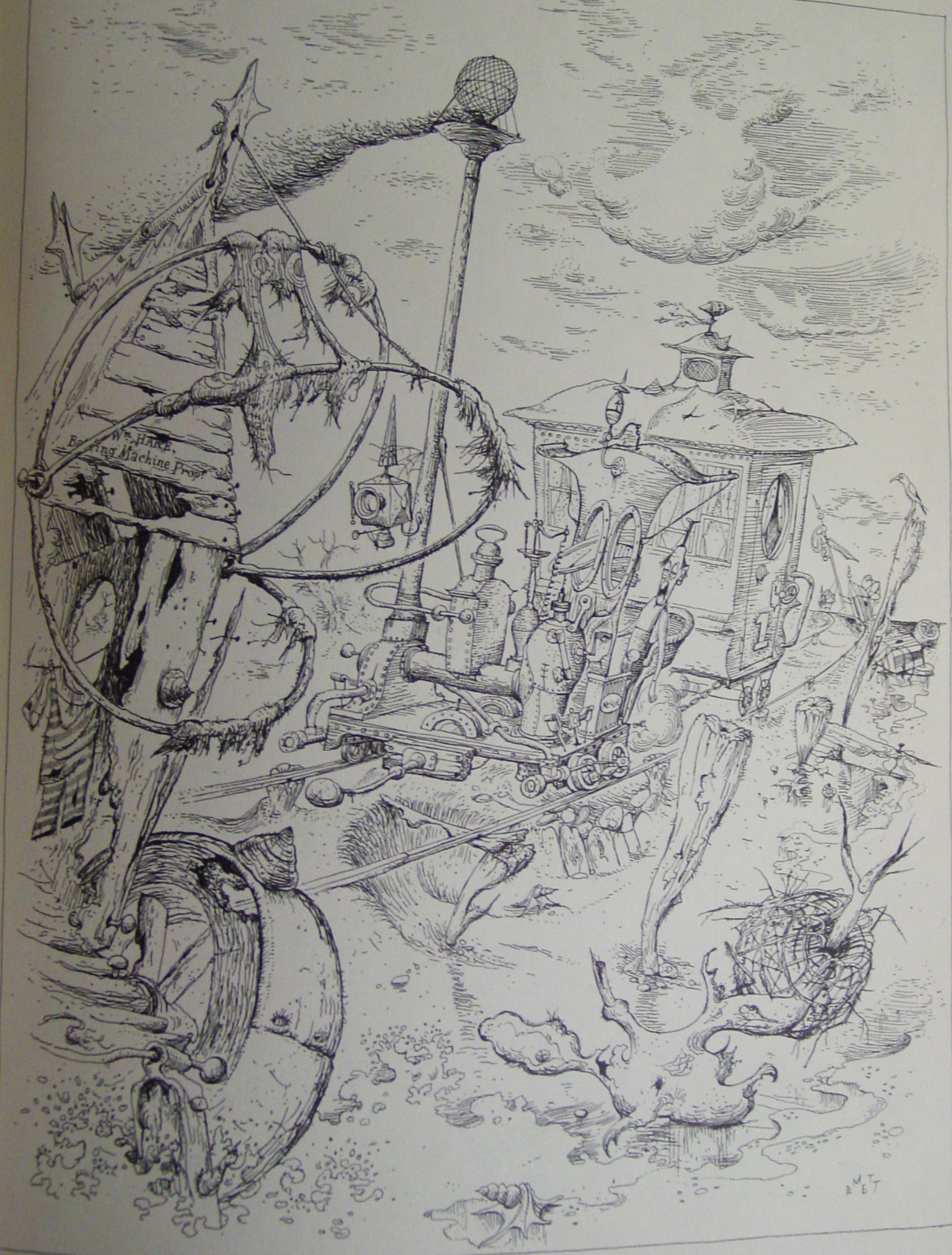

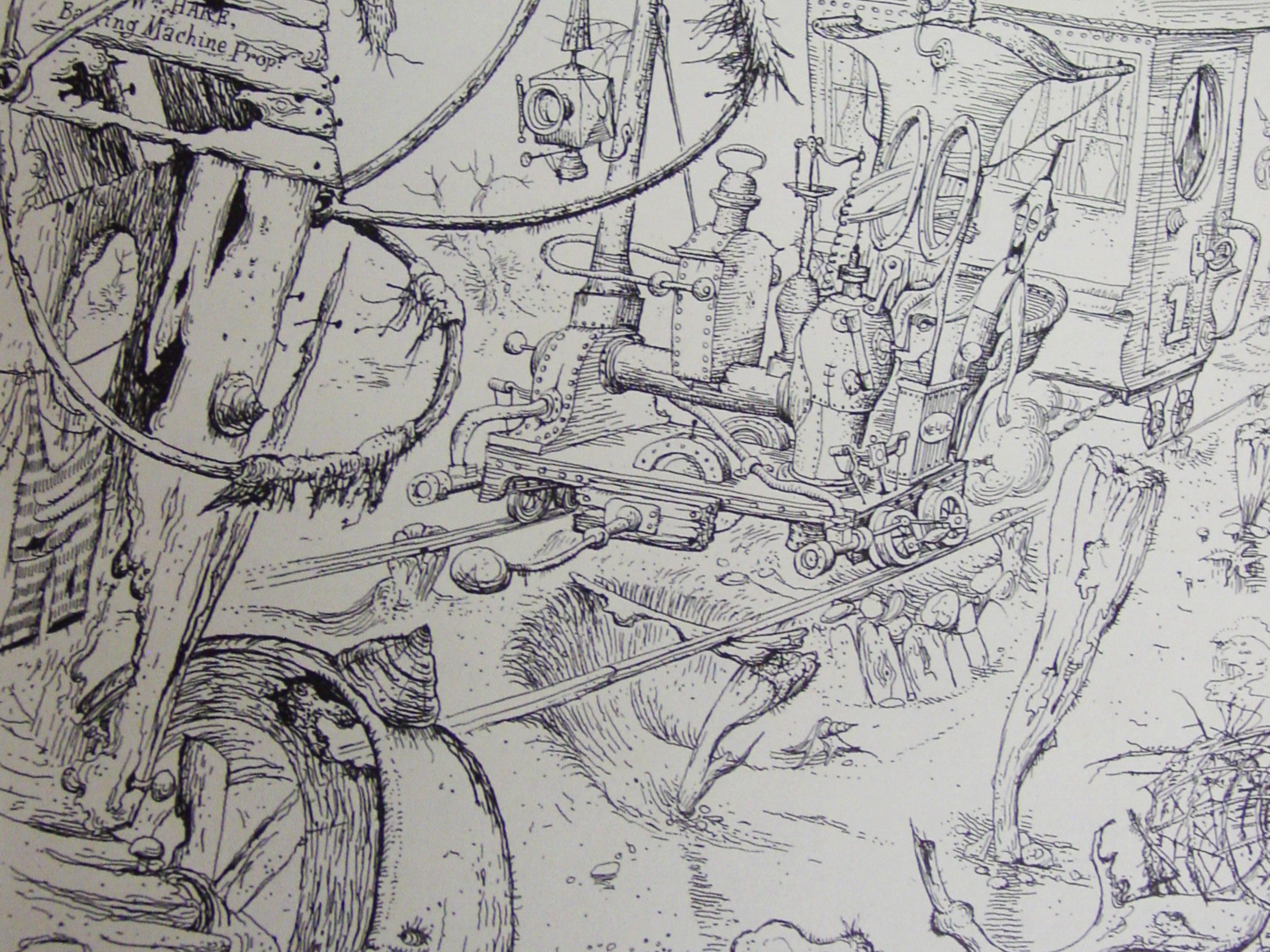

And lastly, around this same time, my grandmother brought back a picture book from London for me called Nellie Come Home by Roland Emmett. Again, another hypnotic world, this one made up of cobbled- together vehicles, machines, houses, and objects — all seemingly fashioned out of a hodge-podge of collected spare parts and detritus. This whole chaotic world teetered on the brink of collapse, but somehow held together — its residents unconcerned, blithely carrying on. If Charles Addams’ world, to me, was made of ink, Rowland Emmett’s was made of line. Dense linear complexity that begged to be studied closely to savor every detail, every element and character, with the result being rewarded continually by that close inspection. My grandfather, seeing how much I loved Nellie Come Home bought me a book called Emmett’s Domain, a collection of his railway cartoons from the 1950s, mostly from Punch magazine, which is what he was mainly known for then.

I scoured that book cover to cover for ages. Still love it.

All of these four world-examples got me onto drawing and making art.

The fifth world was a real-world world — an island in Maine where I stayed in my grandparents’ house for summers as a kid. Many, many days spent exploring the coast, snorkeling, and fishing with my father and brother. In terms of fishing, I loved that I had no idea what might come up from the bottom, a roll of the undersea dice. If it was flounder, cod, or mackerel we would take it back home, cook and eat it. But there were also sea robins – those weird spiky little monsters, dogfish, pollack, or eels, which we would throw back.

I was completely free to roam when and where I wanted. When I was twelve I got a little aluminum boat with a six-horsepower outboard engine, and then the surrounding uninhabited islands became other small worlds available to me. I was almost always alone on them, picking berries, rambling around. The sounds of gulls and passing lobster boats.

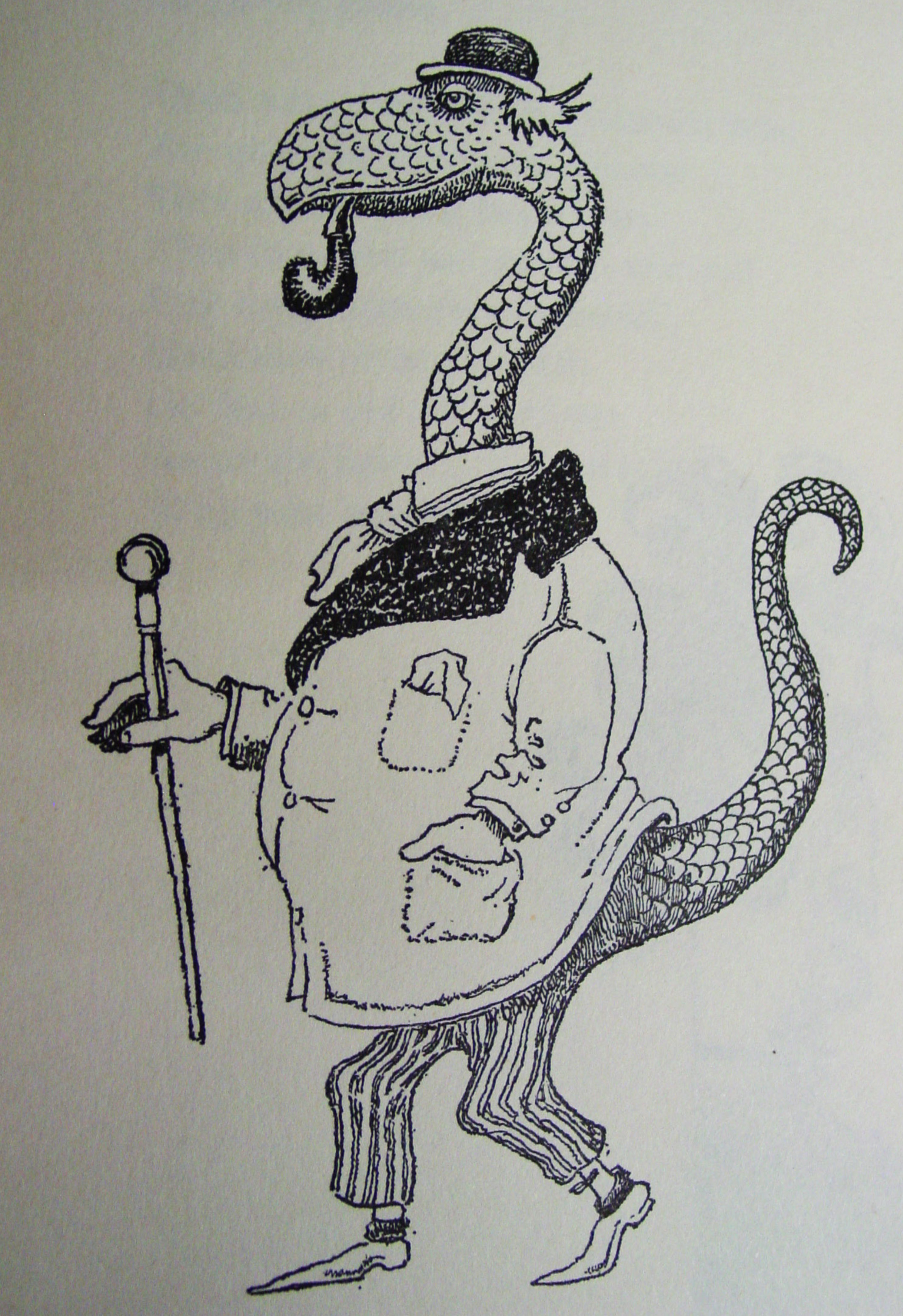

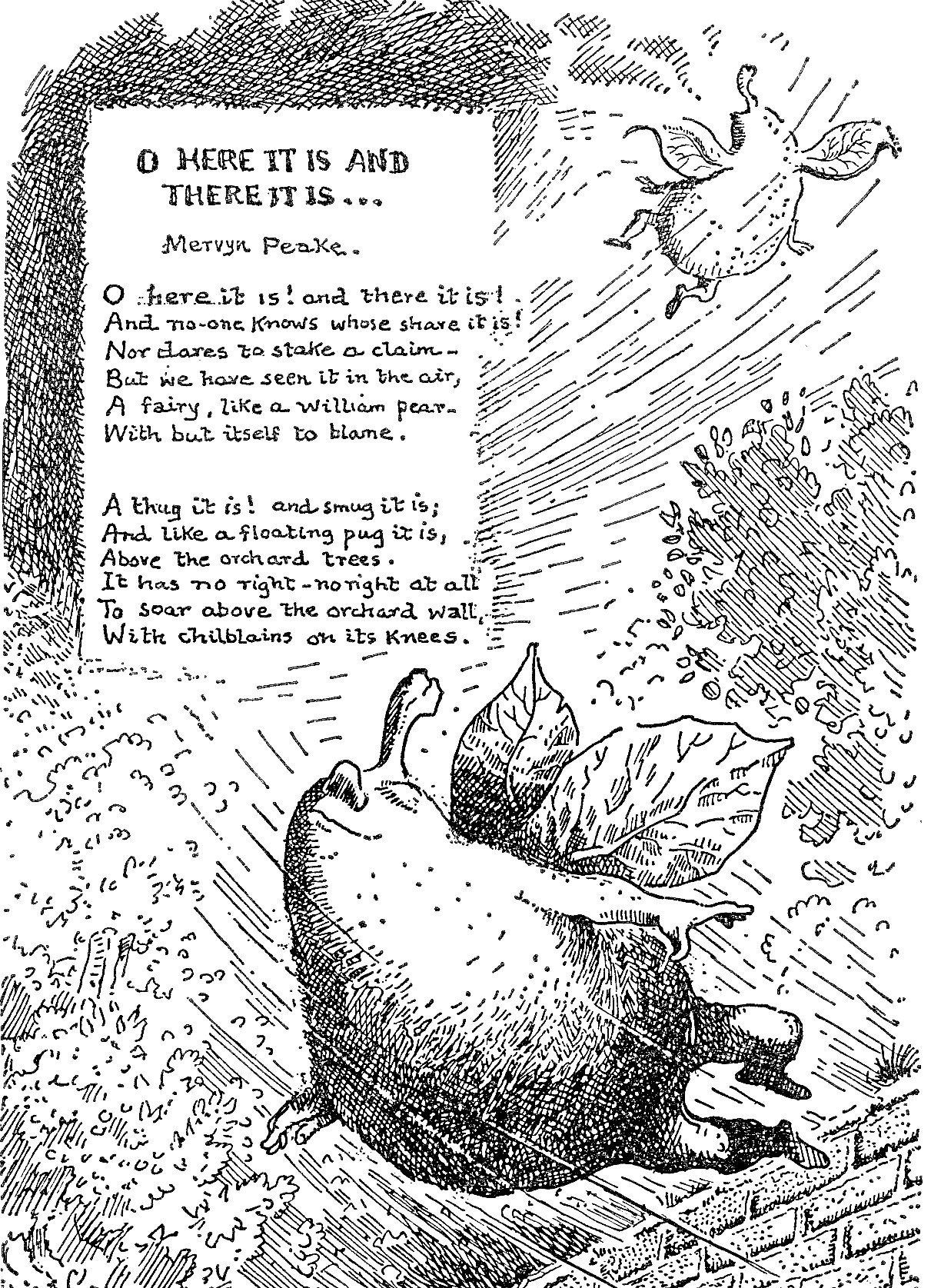

My grandparents’ house, and in particular my grandfather’s little den, provided tons of inspiration, especially from his bookshelves. That was where I first saw a collection of Addams, a volume of old New Yorker cartoons from the 40s and 50s, a book illustrated by Mervyn Peake ( can’t remember which, but he became, and still is, one of my favorite artists and writers), Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense, Slovenly Peter, by Heinrich Hoffman, The Hole Book by Peter Ewell — a rhyming children’s book not-children’s book that begins with a kid playing with a revolver, which goes off, and the reader follows the mayhem caused by the bullet as it travels around the globe on a tour featuring rather nasty stereotypical caricatures of European and Russian characters. Like Tenniel’s Alice illustrations, it was the weird spookiness and exaggerated expressions on the faces that captured my attention.

Mervyn Peake

Follow up question. My brother and I had a world, which I’m still convinced is NOT IMAGINARY. We wrote history books about it, designed rituals, wrote literature and songs. The main idea of it was that animals could talk and lived in total and complete peace. No humans. I love how in your work the distinction between human/animal/creature is sometimes delightfully blurred. It’s all a little wonky and beyond our human understanding. What is your idea about what it means to be human in the real world or in worlds you have created?

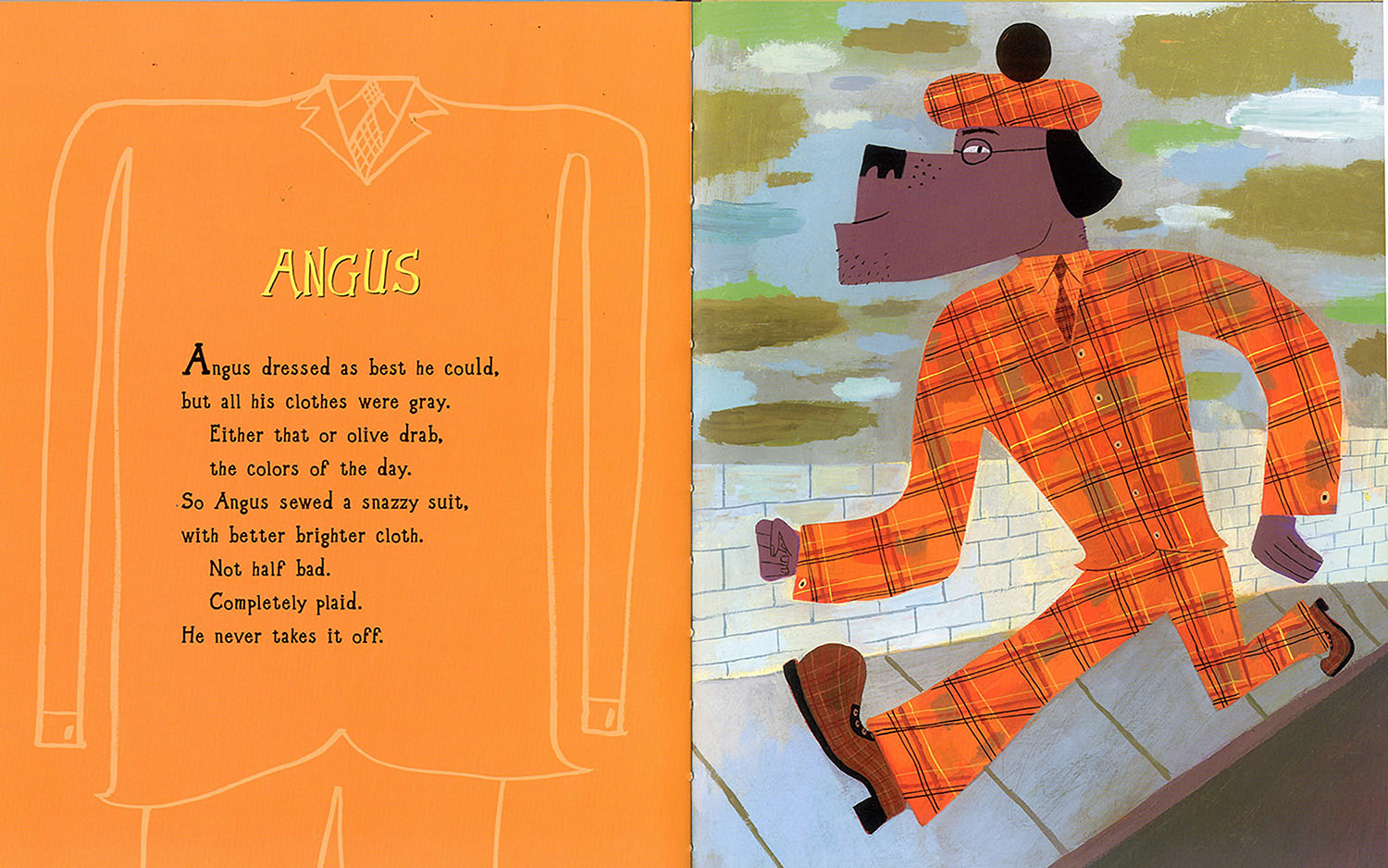

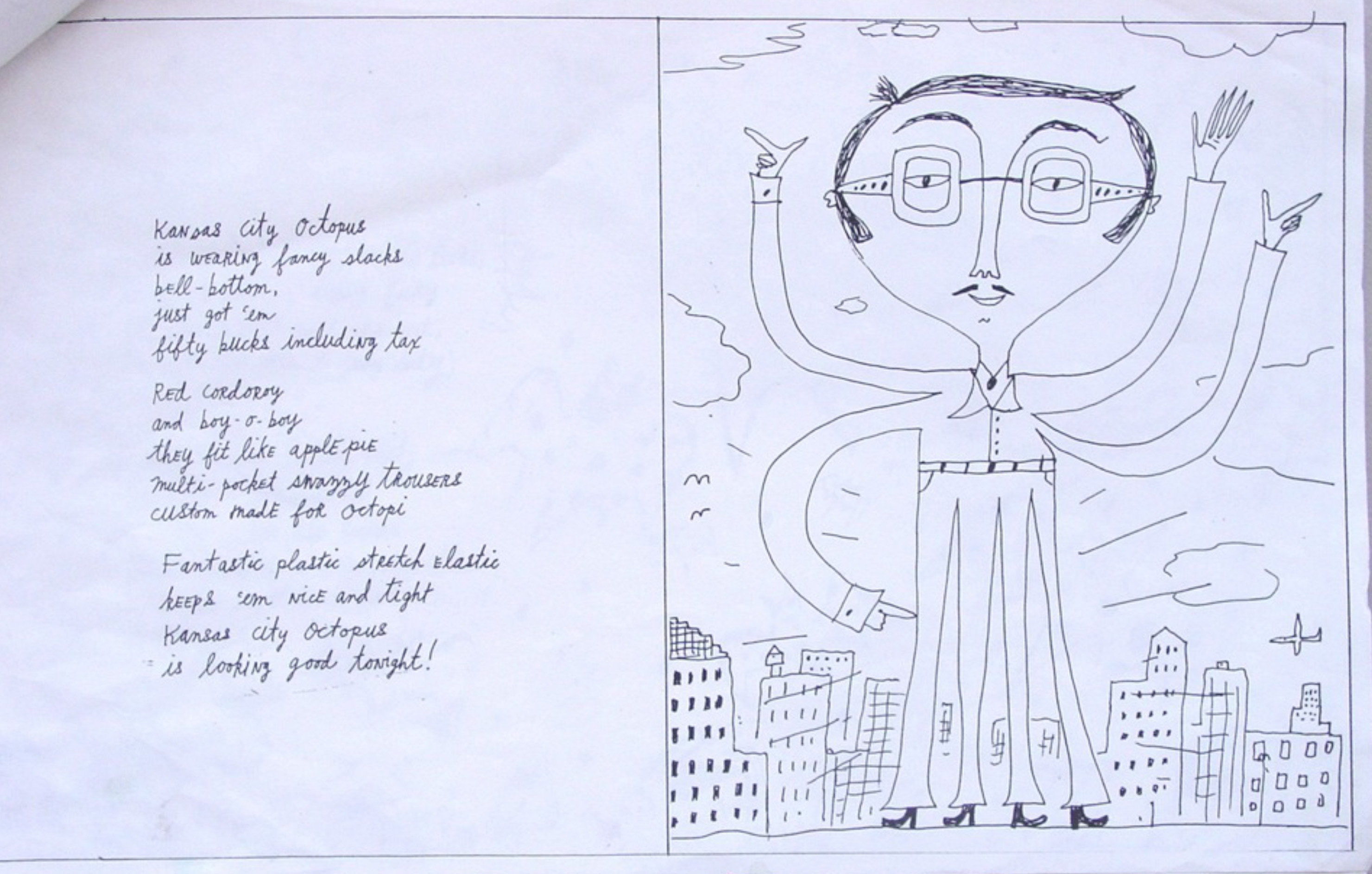

Because I love them, anthropomorphic animals in my books are there whenever there is opportunity — when the poem is not specific or it might be more fun for a character to be part-animal. Sometimes the poems specify anthropomorphic characters — they are described that way. In other instances it’s clearer that the poem is about a human being. But, again, many times what’s written isn’t specific that way, and it comes down to what I think complements the poem best. As an example, in the poems Angus and Dutch Sneakers, the sneaker-wearer could just as well have been a dog-person, and Angus, human.

This question prompted me to go back through my books and compare the human and the anthropomorphic characters. And without exception, the anthropomorphic characters are all smiling! The human characters have a range of expressions, and the animal-animals do as well, but every anthropomorphized creature seems content and happy! I guess we’re better off when we integrate our human and animal-ness.

Anthropomorphic creatures are captivating — a phenomenon or device that has been around for centuries and will always be there for re-invention at the service of lots of ideas and stories.

I teach a class at RISD called Animalia. One of the projects requires engaging with animal anthropomorphism, and the wonderful breadth of how it is employed in the students’ work is always incredible to see.

The humans, human-animals and animal-animals in my books are the deliverers of the spirit of my work, and its substance – character, humor, wordplay, story, color, and visual pleasure.

I’m going to have to pass on the first part of the final question: what it means to be human in the real world — it’s above my intellectual capacity to say anything remotely original or salient on that huge subject. But for my worlds, my books, I’m not sure what it means being human, but I do limit what the human characters do, and the behaviors they exhibit within a certain spectrum that excludes cruelty, violence and strife. What I want my books to do is elicit joy. And to maybe inspire creativity from the reader. The humans, human-animals and animal-animals in my books are the deliverers of the spirit of my work, and its substance — character, humor, wordplay, story, color, and visual pleasure. I hope that a good deal of the core of the communication comes through the faces, the eyes and body language of the characters, a spark of human-ness, whether those characters are actually human, animal-human, or animal-animal. I like to think of that as essential for my work, and I will talk more about that in the question coming up about eyes.

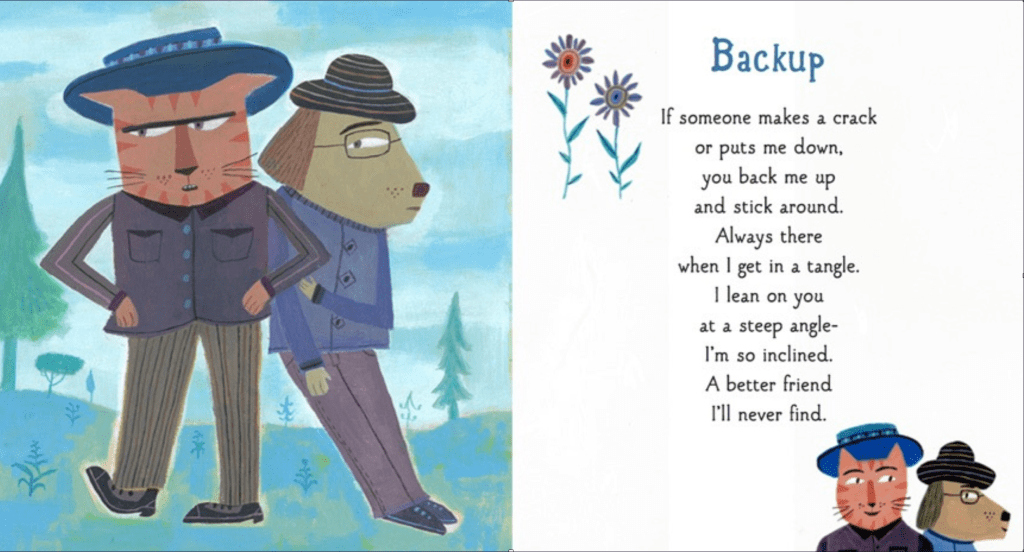

I do want my poems and the books to have an edge, hints of darkness at times, and I’ll talk about that later on as well. I’m trying to think of any poems that push into addressing negative things, meanness or the like. There is a poem in my book Hypnotize a Tiger called Foodie Bully. Not a nice character. And there is a poem in Up Verses Down about a kid whose parents feed him pet food, and he is none too pleased about it. Across the spread on the facing page is one of the weirdest poems to appear in my books. It’s called The Omnivore, and that’s where the marsupial salad / his coupon was valid rhyme takes place. And there is a poem called My Backup from my book We Go Together!, which addresses bullying, but from the perspective of a kid who has a good friend who sticks up for them when they’re dealing with it.

Follow up on the follow up, I’m fascinated by the eyes in your drawings. They’re frequently sorta human-eye-shaped, they’re speaking eyes – often mischievous, knowing, amused. Can you talk a little about how you draw eyes? And about what these creatures are thinking!

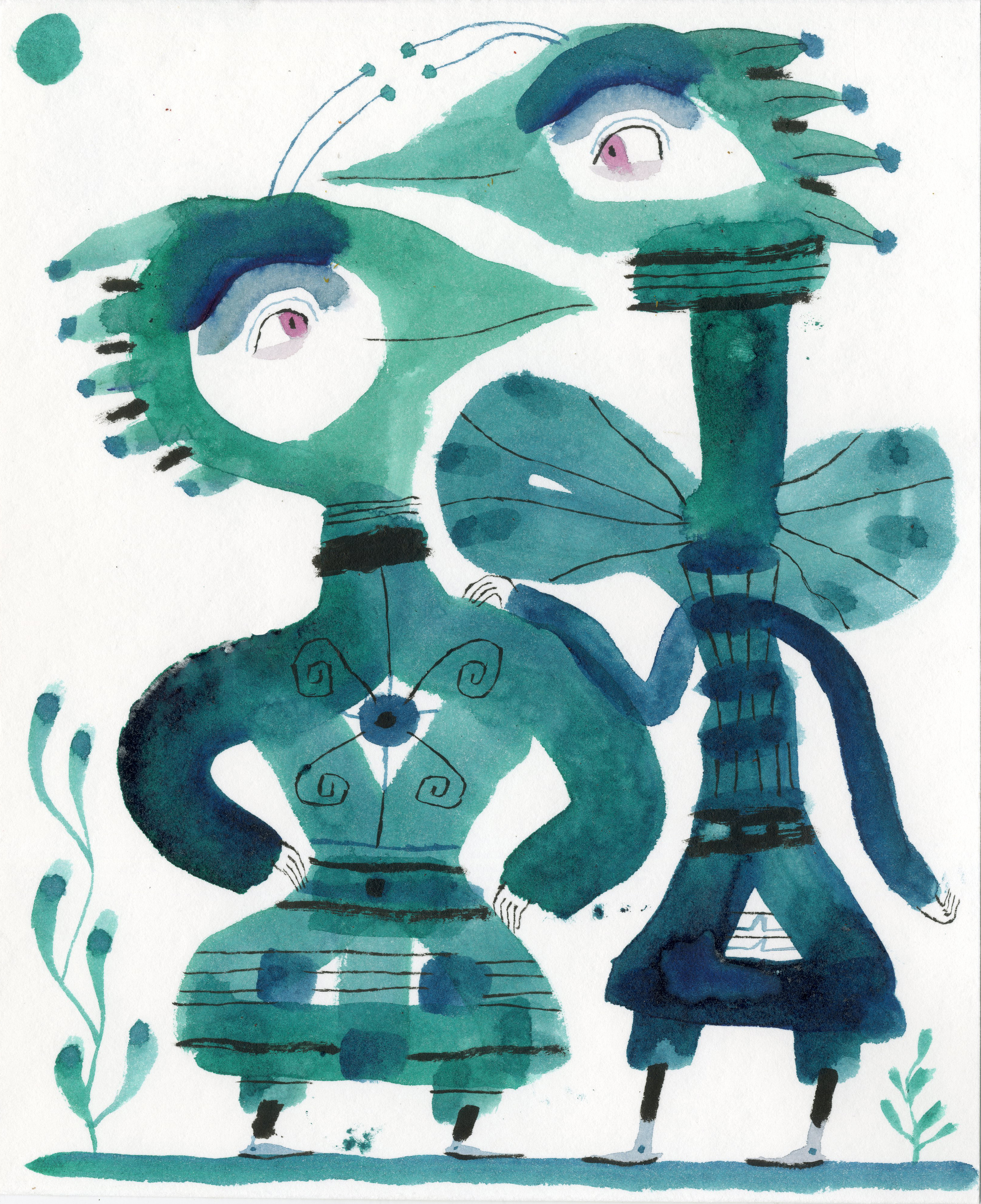

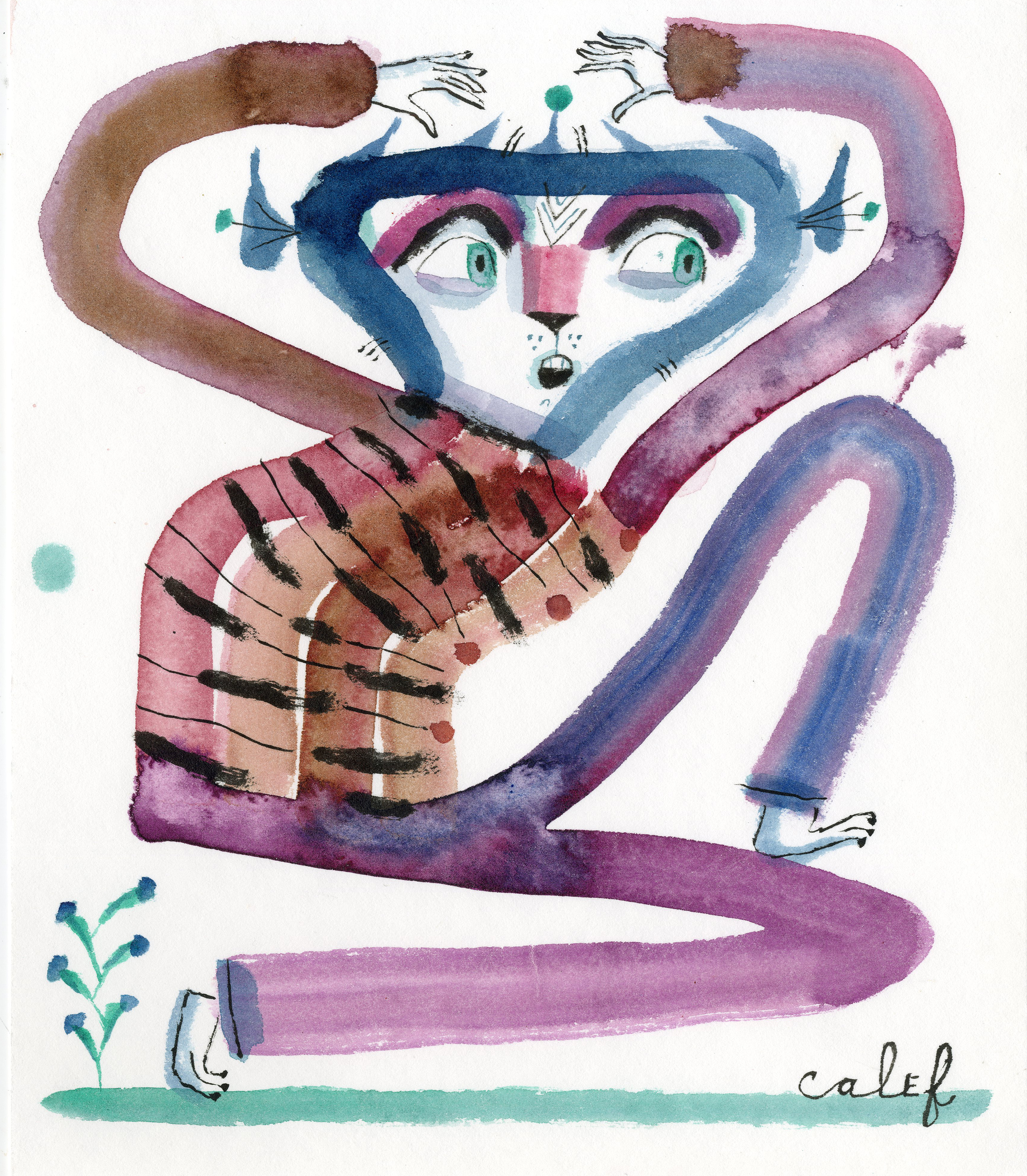

I think that when I achieve some of what I’m aiming for in that way with the characters, there’s a balance between their formal qualities — what they’re made of visually — shape, color, line, surface quality — coexisting with a kind of very specific inhabited presence and expression that emanates from them …

This is an important aspect of my work at the moment, thank you for posing these questions. I have been focused for a while now on further refining and foregrounding the aspect of specified expression in my personal drawing practice. It’s something that I think about a lot — what I want to come through from my characters to the viewer. The point is to develop it in my personal work, but then bring it into my kids’ books with more nuance and impact than I’ve done previously. I think that when I achieve some of what I’m aiming for in that way with the characters, there’s a balance between their formal qualities — what they’re made of visually — shape, color, line, surface quality — coexisting with a kind of very specific inhabited presence and expression that emanates from them, and when these aspects congeal, I like what happens. That’s the best I can describe it. I feel like there’s something magical when that comes to life in these personal drawings, that aren’t planned at all, improvised. I’m working on a book for Penguin Random House that is not rhyming, it’s not verse or poetry. Very visually driven, for a young audience. New territory for me. I really want that aspect of inhabited characters to make its presence felt not only through the eyes, but the turn of a smile, the subtle lift of an eyebrow, the tilt of the head and then there’s the hands — I also really want the hands in the current book to be expressive in a way that they haven’t in my previous ones. Something I focus on with my students — who draw beautifully — is to get the hands of their characters to speak in tandem with faces and nuanced body language.

When I think about children’s books I have loved and still love, it’s not because of their technical skill or because they’re the best of their children’s book category as defined by publishers. Or because they appeal to children in the way people think children like. It’s because they have some sort of perfect honesty, like children do. No other way the creator could create it cause it’s an expression of their own imagination. I’m sure you’ve been asked about your favorite children’s authors a million times! But I’m curious about what draws you to the books you love. Or music, films, art, whatever!

It’s hard for me to identify sometimes what might draw me to a piece of art in whatever form, it would have to be on a case-by-case individual basis. I can list a few of my favorite picture books and creators:

Abol Tabol by Sukumar Ray, This is New York and any other book in the “This Is” series by Miroslav Sasek, A Hole is to Dig by Ruth Krauss, A Tale of Two Bad Mice and Jeremy Fisher by Beatrix Potter. A Long Long Song by Etienne Delessert, My Friends, and lots of other books by Taro Gomi, Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor by Mervyn Peake, Grasshopper on the Road, and many other books by Arnold Lobel. May I Bring a Friend? by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, Fish Head by Jean Fritz. Anything and everything created by Tove Jansson. Anything and everything created by James Marshall. The Butterfly Ball by Alan Aldridge, Duck, Death and the Tulip, by Wolf Erlbruch.

Same vein … I always feel like poetry boils things down to their essence. It’s a little harder to hide behind extra words or elaborate plots. Although clearly poetry can and has told stories – and you, yourself, can create whole worlds in a single poem! How did you settle on poetry as a medium?

To leave the studio and give it my full attention, I took six weeks and went to one of my favorite parts of the world, which is in southern India — Tamil Nadu state, with the intention of returning home with a complete book dummy — that was my goal.

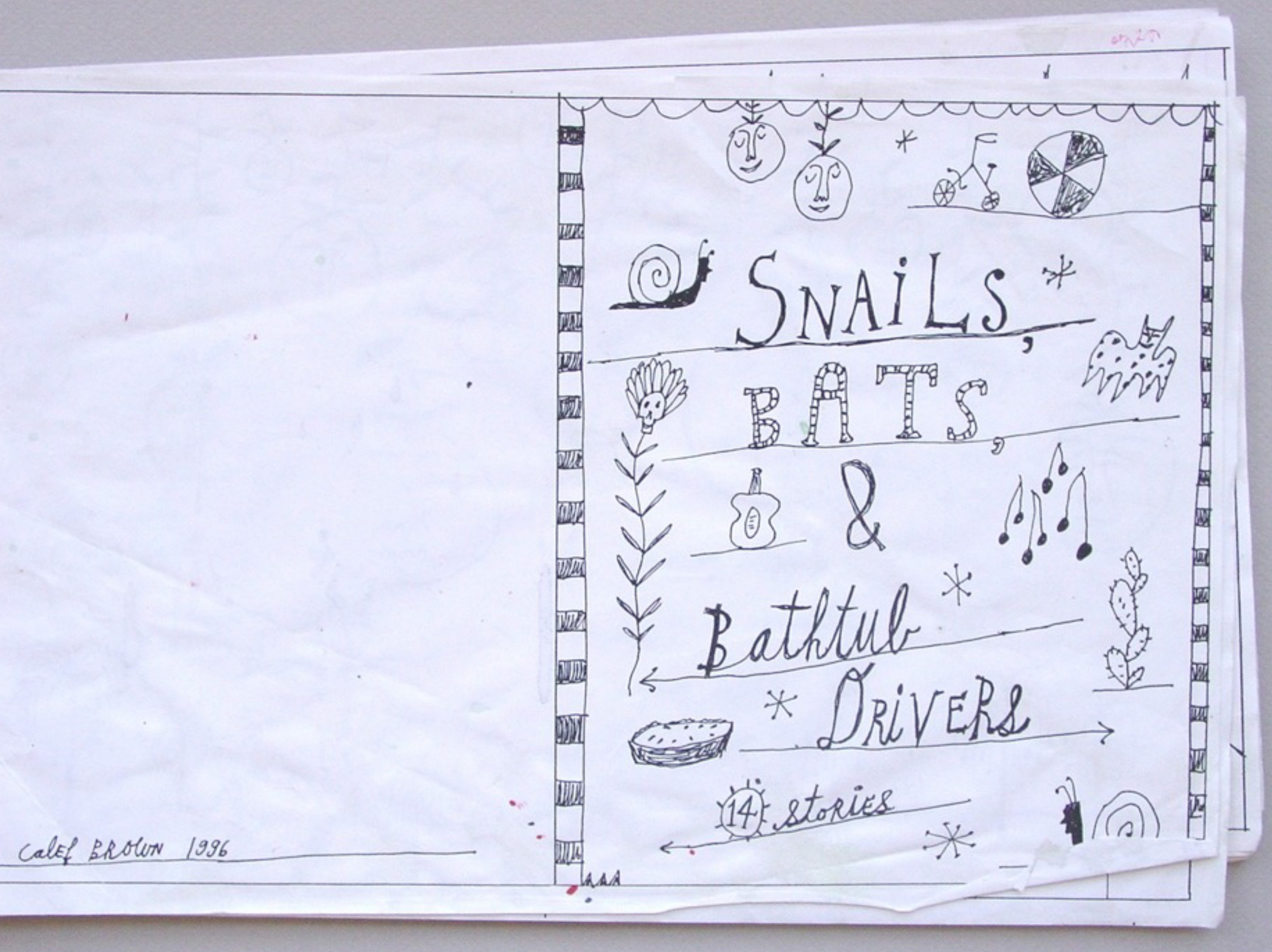

In 1996 I was burnt out from the pace and workload of freelance illustration and wanted to create something fully my own. I had been told many times by friends, and had for a while recognized myself that my work could lend itself well to children’s books and being appropriate for a young audience. Picture books are the main thing that got me going on the way to being an artist and illustrator, so I definitely wanted to try my hand. I knew I wanted to create a book, but I had no idea of anything specific beyond that. I was super-busy with work and the hectic pace of the editorial illustration freelance mode I was in. I figured I needed to get away from that in order to concentrate or it wouldn’t happen. To leave the studio and give it my full attention, I took six weeks and went to one of my favorite parts of the world, which is in southern India — Tamil Nadu state, with the intention of returning home with a complete book dummy — that was my goal. But again, I had no idea what I wanted to do, really. I didn’t have any notes, sketches or basic ideas for anything — I really just went cold with some art supplies, blank sketchbooks and sort of a loose plan of travel, beginning in Chennai and meandering south.

What I found that I could do is to create short stories in rhyme that were inspired mostly by music — song structure and lyrics, rhythms and musicality of language, and also from some of the nonsense verse I mentioned earlier — Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear’s limericks and also things like schoolyard rhymes, the meme equivalent of my kid-era.

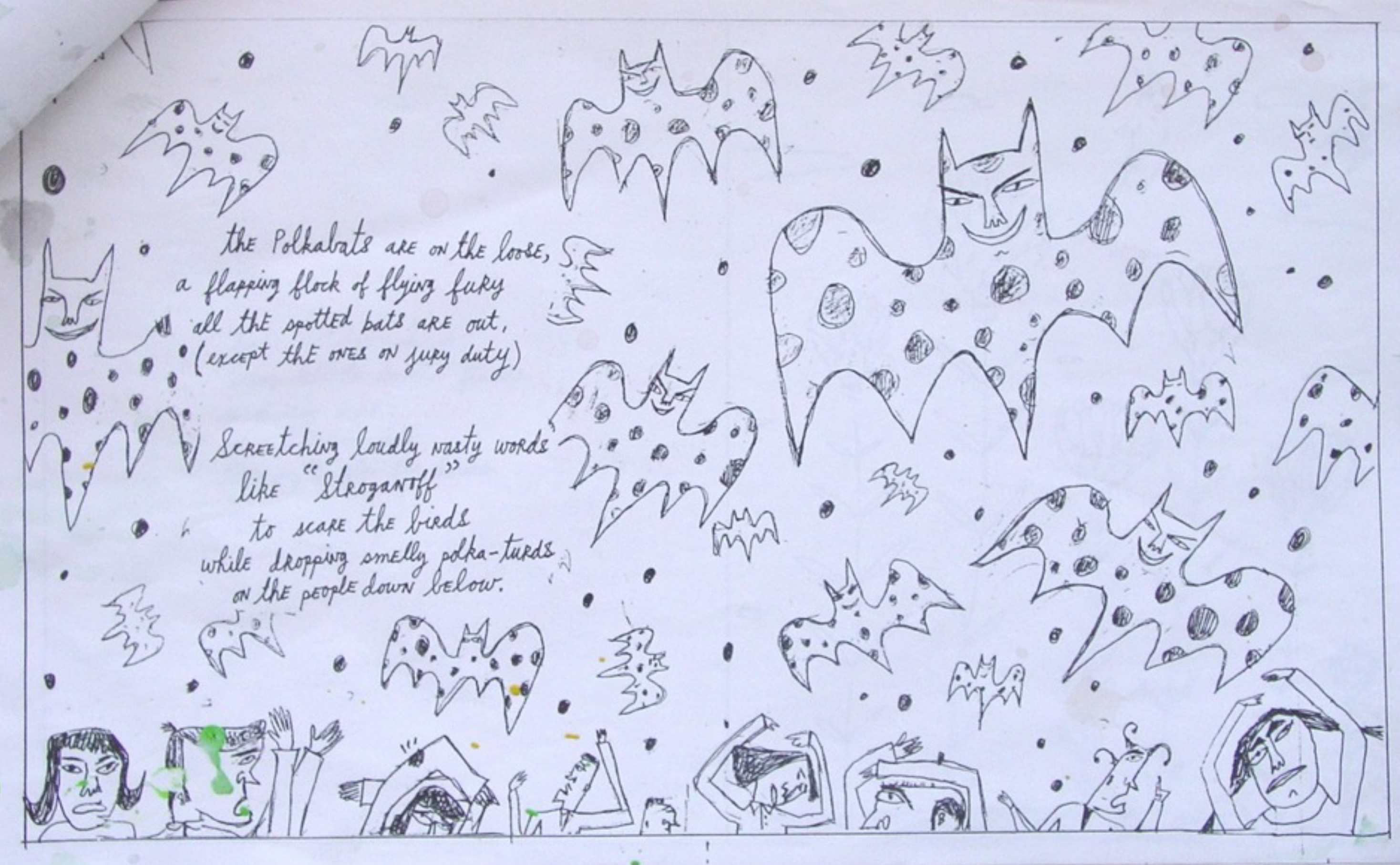

I got into a rhythm of getting up in the morning and working for a while then going out until it got quite hot, then coming back to my hotel and napping, waking up and working for a while, going out again in the evening to have dinner, wander and sightsee, coming back and working until late at night. I would stay in one place a few days and move on. I didn’t go into this, as I said, with the intention of employing rhyme, or writing poetry, but I naturally landed there, in part through a process of elimination. At first I tried to play around with traditional story modes and structures — following a consistent character or characters through a narrative arc, and things like that. Very quickly I realized that I was lost and had no foothold, experience, or process for trying to do something original in that way. What I found that I could do is to create short stories in rhyme that were inspired mostly by music — song structure and lyrics, rhythms and musicality of language, and also from some of the nonsense verse I mentioned earlier — Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear’s limericks and also things like schoolyard rhymes, the meme equivalent of my kid-era. When I focused on structuring the pieces like short songs, it didn’t seem like I had to struggle. Once I got a few of these rhyming story-poems going, the path of what this book would be was clear. Sometimes the stories came out of a sketch I made of a character when free drawing, sometimes the words came first and the process was similar in some ways to doing an editorial illustration where you’re given the text and respond to it. What I ended up with was an ink line-drawing dummy with fourteen of these stories. Again, I called them stories not poems. I remember going to a Xerox shop in Madurai, and having a couple copies run off of this dummy, which at the time was called Snails, Bats and Bathtub Drivers, and later became Polka Bats and Octopus Slacks. I chatted for a bit with the owner of the shop about the project, and he was very complimentary — my first positive review.

When I returned home, I sent the dummy out to a dozen publishers. I didn’t know how to go about it, but I just found names of some editors and mailed them out. I received responses from six of them, all rejections, and then one enthusiastic response from Margaret Raymo at Houghton Mifflin, who published the book and I went on to do many more books with her, a great editor.

But back to your original question about how I landed on poetry. Once again, it really was a process of elimination and a recognition that my love of music and all the time spent listening carefully to lyrics and structure and storytelling in song was a solid base from which to draw in creating something that was mine.

Some more about music. I’ve been playing instrumental finger-style guitar since my teenage years, inspired by folks like John Fahey, Leo Kottke, Mississippi John Hurt, Jorma Kaukonen, Robbie Basho and many others. I have created only about thirty or so complete and resolved songs, but mostly my playing is meandering, improvised, riff-based and the like. It’s just for myself, a meditative practice in a way, and I have many hours of recordings of noodling and just playing around. There’s a direct connection between this practice to my books — I’ve gotten a lot of ideas for beginning a poem from guitar riffs, for the rhythm and cadence of the musical phrase, I associate words with it, and it becomes a seed in the process of building a poem. I focus on a series of notes, something catchy that makes words come to mind, and I have a place to start. I love the idea of building out from one line, the germ of a narrative idea, and that becomes an armature, soon a structure, and then finally a story-poem with a beginning middle and end, even if it’s just sometimes as minimal as a half-dozen lines.

I’ll give a couple examples of how an instrumental guitar piece led to a poem that appeared in one of my books. While the poems that come out of initial inspiration from my music are usually only a beginning line of text from one riff, these are two examples where a fairly complete instrumental song was more fully related to the complete poem that eventually came out of it.

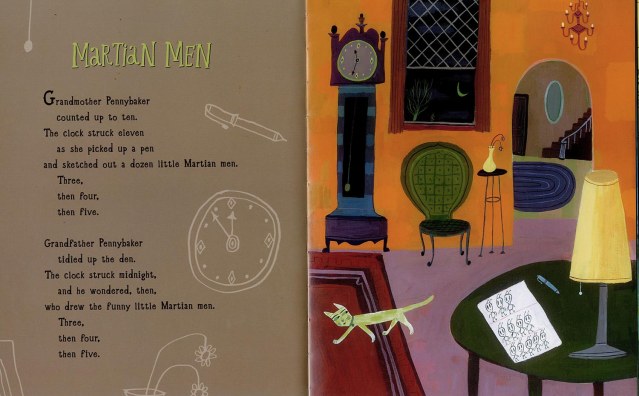

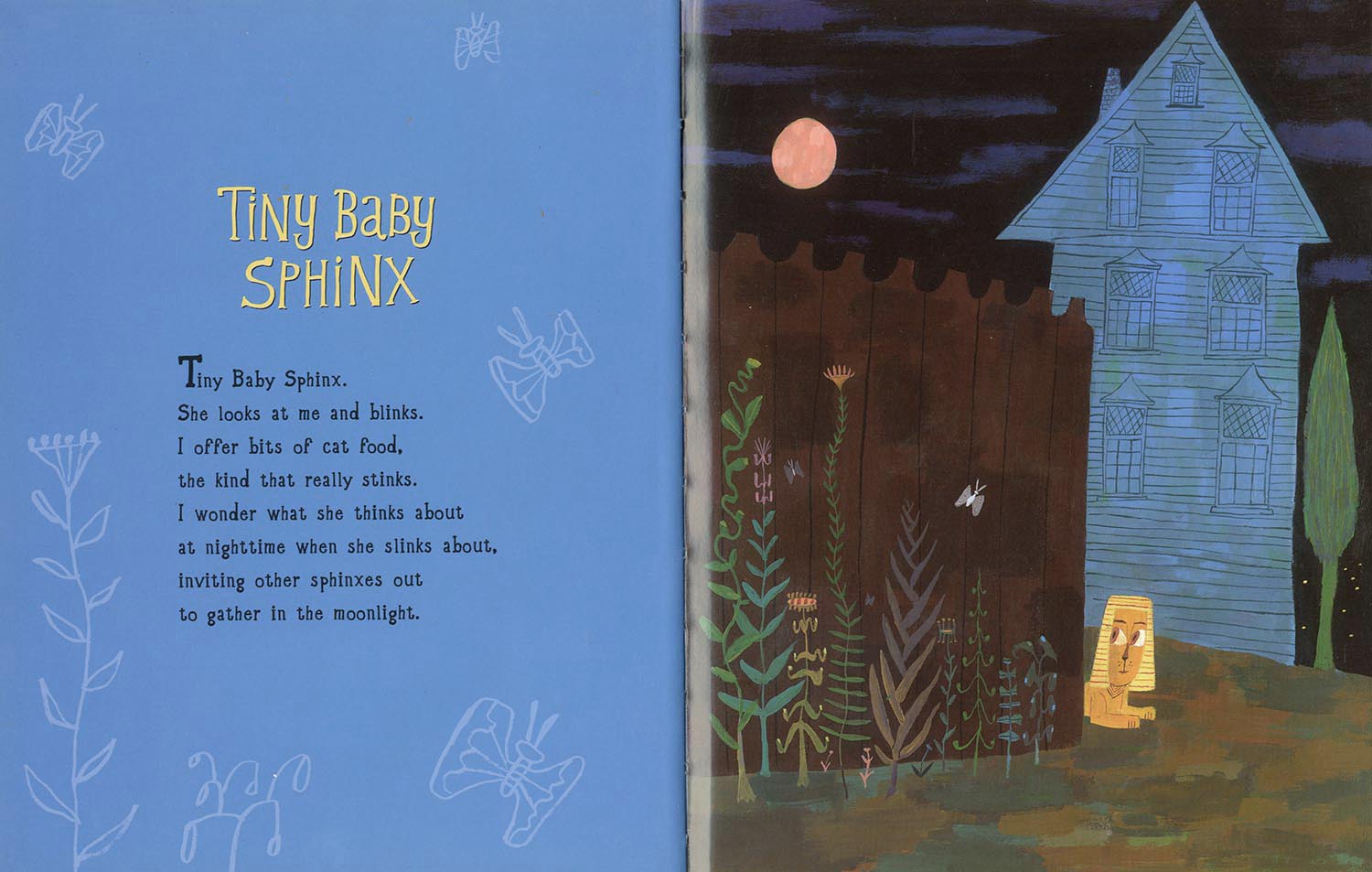

The first is the song that inspired the poem Martian Men, in my book Flamingos on the Roof.

Here’s the complete poem with illustration as it appears in the book:

Here’s a recording of the song:

And here’s what I first wrote down in listening to the song and free-associating words with the music:

Who drew those martian men?

Who drew those men?

Who drew those martian men?

Who drew those men?

Who drew the funny little martian men?

Three, then four, then five

Three, then four, then five

Three, then four, then five

Three and then four and then four and then five

Three, four, then five

Three then four and after that comes five

Three and then four and then four and then five

Three, four, then five

Three then four and after that comes five

Who drew those martian men

Who drew those men

Who drew those martian men

Who drew those men

Who drew those martian men?

Who drew those men?

Who drew those martian men?

Who drew those men?

Who drew the funny little martian men?

Three, then four, then five

Three, then four, then five

Three, then four, then…

five

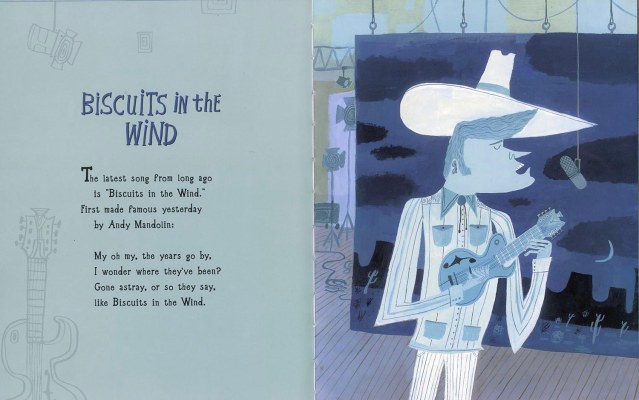

One other example is the poem Biscuits in the Wind from the same book.

Here’s the complete poem with illustration as it appears in the book:

A recording of the song:

And again, the first words I wrote down when listening to it and imagining lyrics/poem lines:

(intro)

Here’s a song called Biscuits in the Wind

Sung for you by

Andy Mandolin

Gone

Like Biscuits in the Wind

Gone

Like Biscuits in the Wind

(buildup)

Oh! How the days go by.

Oh! Days go by

I wonder where they’ve been.

Gone

Like Biscuits in the Wind

Gone

Like Biscuits in the Wind

Gone astray

Like Biscuits in the…

Wind

For anyone who might be interested in my guitar music here’s a link to my soundcloud:

And a link to a recorded reading of Flamingos on the Roof with short guitar pieces randomly placed in between the poems:

Similarly, there’s always so much darkness mixed in with the lightness in children’s books. Some of them, historically, are downright scary. But I always think children are fine with things we might consider scary and scared of things we consider safe. Do you think about that balance of light and dark in your work?

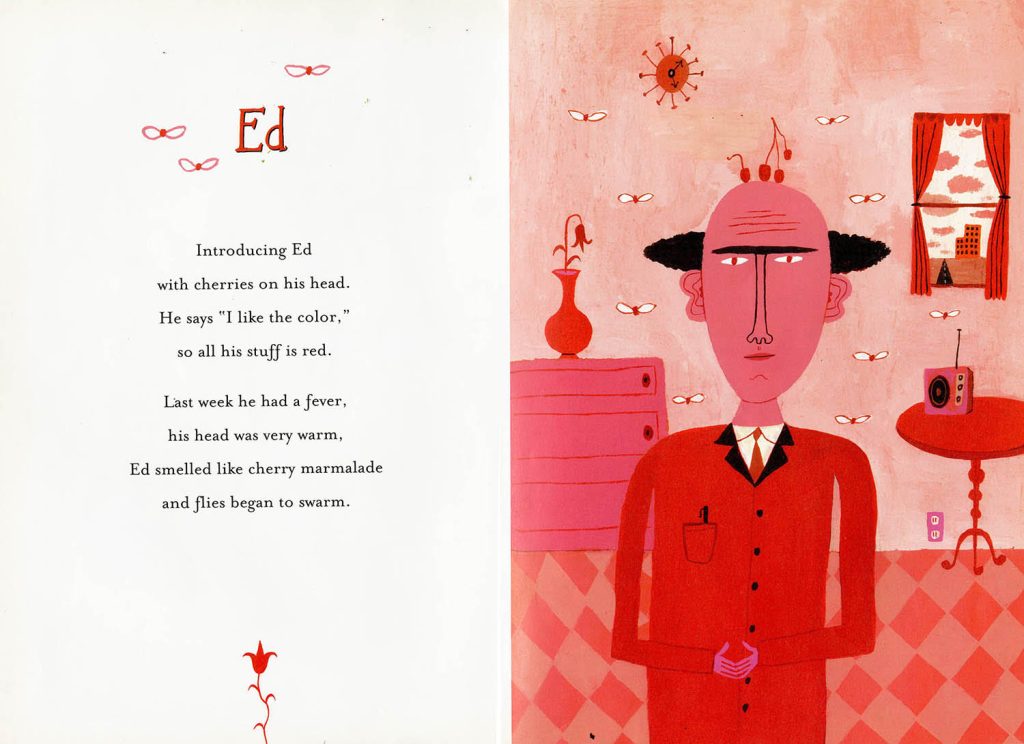

I do think about a balance of light and dark. I could describe it in terms of light and dark, but I always want there to be slight edge, a tinge (or more than a tinge ) of weirdness that’s really not necessarily dark in a way, but intriguing, or strange, even in the most joyful and fun poems in my books. The poem Ed is a good example of that playful weirdness that I try to get to.

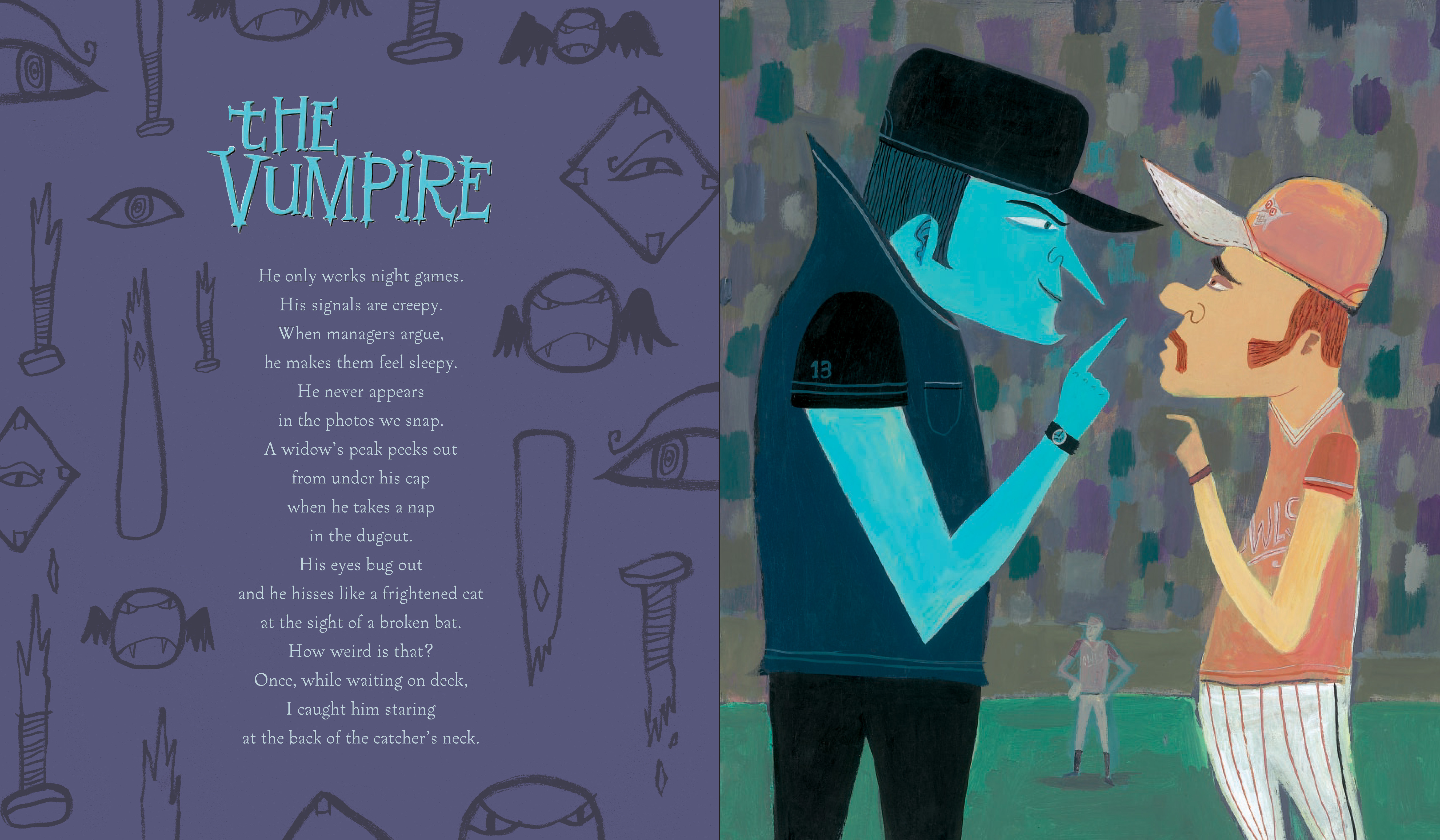

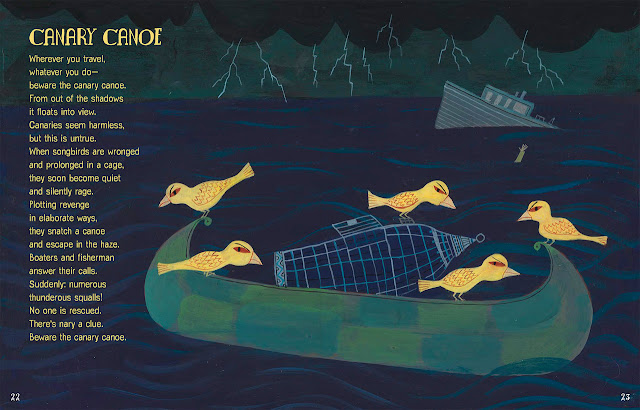

In terms of darkness in a more direct way or a playful version of it, I have done two books that are Halloween-themed, and this is where I get to play off of my love of Charles Adams and old monster movies and the tropes and clichés around spooky Halloween-esque characters and the like. The first book is called Hallowilloween – Nefarious Silliness, and it’s a combination of my take on classic Halloween entities – witches, werewolves, vampires, mummies, ghosts, and then there are my own invented characters, which seem to fit into that world. The other book that I did in this mode is called The Ghostly Carousel, which was published in 2018 and it also riffs on classic characters and has many of my own as well. A favorite in that collection is titled Canary Canoe.

Have you ever animated your art? I’ve thought about it quite a bit – what your drawings would be like. I’d like to see how some of these three-legged or snake-bodied fellows move. What sort of music would you imagine with your work? Or noises?

My art has not yet been animated apart from some very short tests. I’ve had some false starts in terms of developing my books for animation that didn’t come to fruition. I recently regained all the rights including dramatic to six of my favorite books and I’m interested in partnering with a studio or individual within the industry to explore possibilities for translating the books into animation. I’m also right now pitching a treasury or greatest hits compilation of four of my books, which, given that they came out from 1998–2005, the poems could be introduced to a new generation. Back to animation, I would definitely be excited to see how my characters could move, how they would express themselves, the voices that they would have and of course music and soundtracks. In 2007 I collaborated with a band called Clementown who wrote and recorded a suite of songs based on the 28 poems in the first two books — Polkabats and Octopus Slacks, and Dutch Sneakers and Flea Keepers. The songs are great and it’s a grab bag of all sorts of musical genres and styles. The album is available on Spotify and Apple Music under the band name Clementown. In 2010, we did a performance together at The Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis. The band performed the songs and I did live drawing on the screen projected behind the band, and even sang a little. It was a lot of fun.

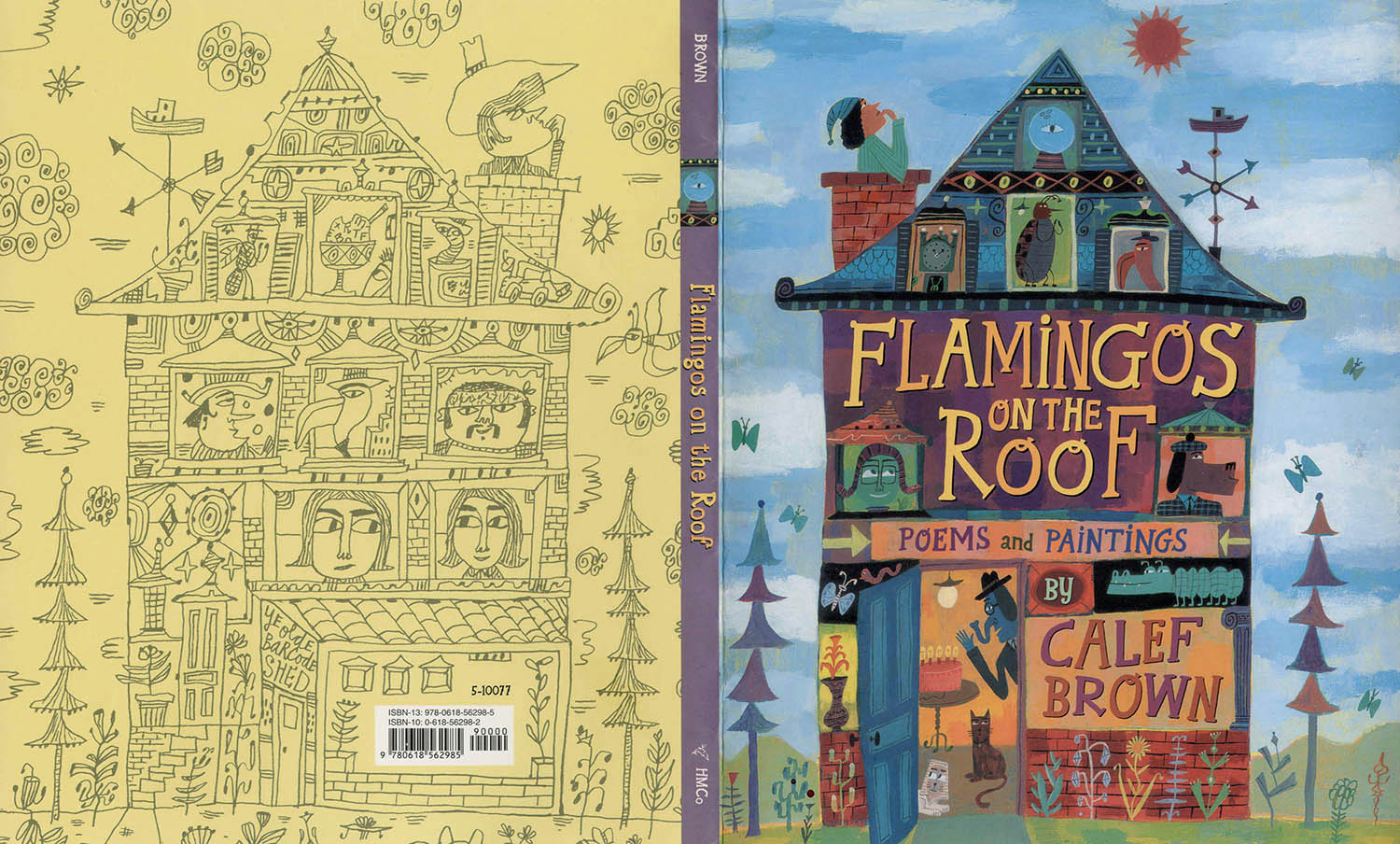

Aside from the art and words, I really love the design of your work. It all feels like part of this perfect package. How involved are you with design or your books?

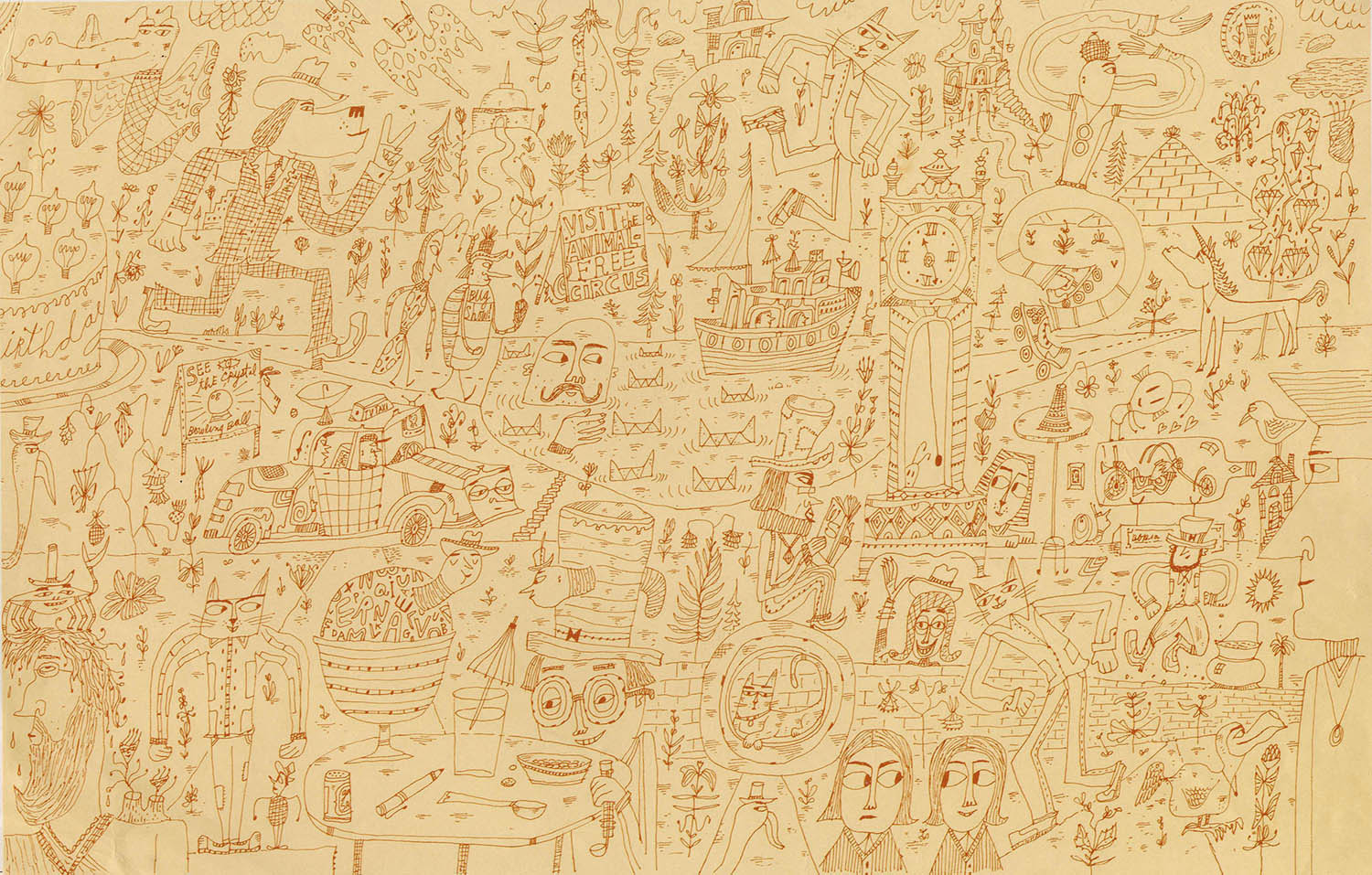

I’ve been quite involved in the design of my books from the beginning. The first two were designed in collaboration with a friend, a designer for a record company, but I’ve taken over the major design aspects since. For maybe my favorite book, Flamingos on the Roof, I created a text font and controlled every aspect of the design — the integration of line art with the full color illustrations, the end papers ( a line drawing with a hide and seek element and all the characters in the book) hand lettered titles, painted contents page, color choices for each page with the poem text. Everything.

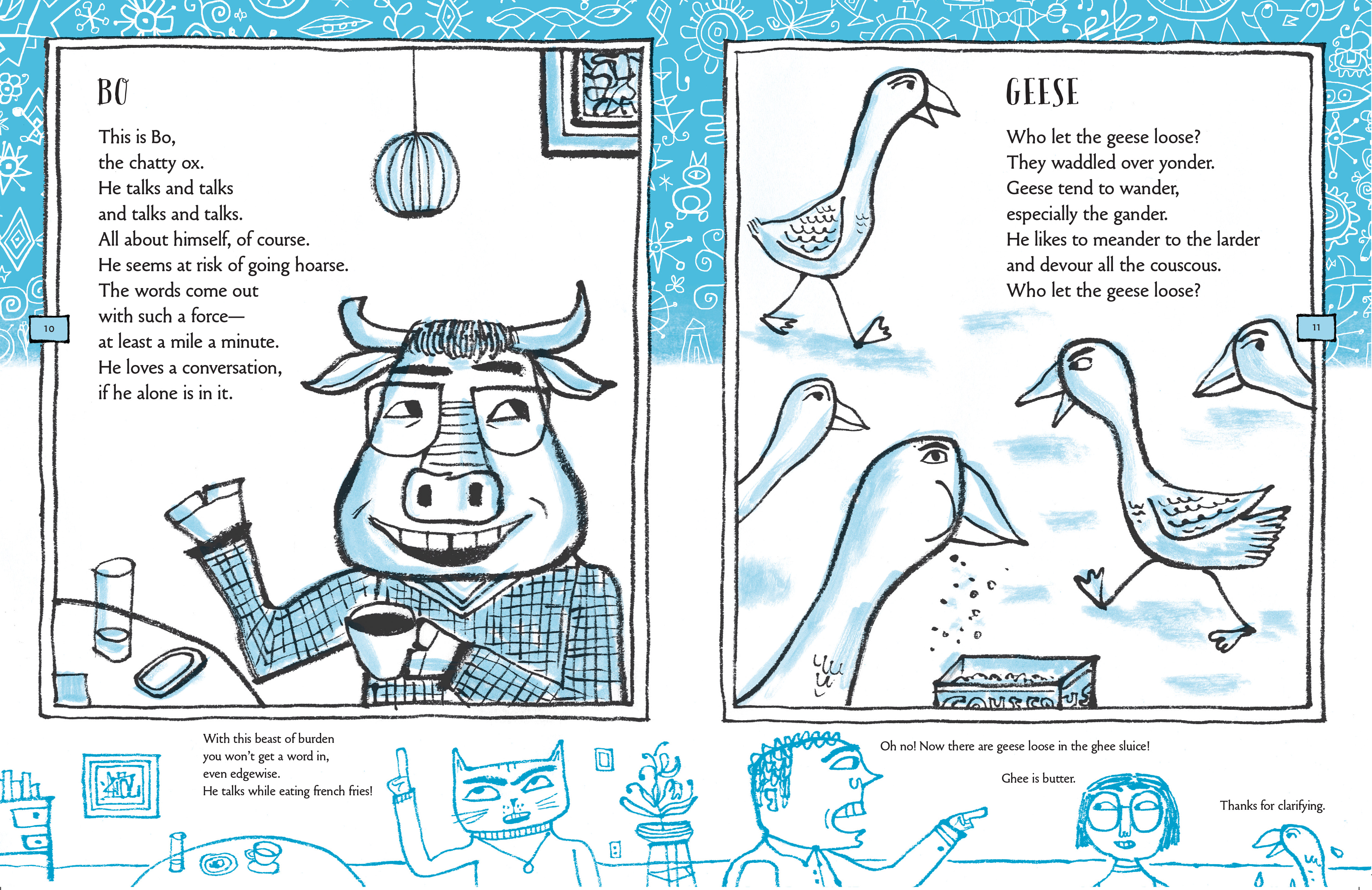

The first book I did aimed at middle grade readers — Hypnotize a Tiger, is printed in two colors, black plus blue, and I came up with the page design, which includes using the lower border for blue line drawings that expand on the narratives in the poems above. Some have a kind of a Greek chorus effect, or extend the rhyme scheme and content of the poems, sometimes they’re wordless. Some examples below.

The book I’m currently working on for Penguin Random House is not poetry, but minimal prose and very visually-driven, aimed at young readers. For this one I’m interested in an active collaboration with the designer and editor, and giving over a lot of control compared to the independence I’ve had with previous books.

It feels strange to me, sometimes, that there’s such a distinction between what’s for adults and what’s for children. It seems driven more by the market than reality sometimes. We’re all evolving humans! Have you ever felt confined by the label “childrens’ book author”?

I, of course, have awareness that what I’m creating should foremost be appropriate for children, but with my books, I’m creating them as much for myself as anything or anyone else. So, in terms of that distinction, I want them to be appreciated by everyone — kids of all ages, including teenagers, and adults as well — especially those parents who may have to read books over and over again to their kids who favorite them. I will say there is definitely a difference in the language, ideas and humor between my picture books, and two fairly recent books — Hypnotize a Tiger and Up Verses Down, which are aimed at middle grade readers and up.

I’ve never really felt confined by the children’s book author label but perhaps somewhat by the children’s poet definition. That is partly because I’m not sure I ever fully embraced the characterization of my work as poetry. I’ve addressed this earlier in the interview a few times and talked about why that’s the case. This is the reason why the first two books are called stories, not poems. I did change over to calling them poems but really out of convenience. I will say that I sometimes wish my books were mixed into the picture book sections of bookstores and libraries, and not in the poetry sections. I guess I have mixed feelings. I feel like I have carved out a unique place within the world of so-called children’s poetry, but I feel limited by that categorization at the same time.

My husband, who also admires your work very much, added an idea/question because he was thinking about it too. He thought you might like Tomi Ungerer, because he uses words children might not immediately understand, but they totally “get.” And I know with my boys they never wanted to be talked down to. I taught them words and they taught me words they invented that I still use. So I guess the question there would be about how you choose words you use for childrens’ books, and if you feel limited in that.

Thanks for the kind words from your husband. I love Tomi Ungerer, a unique artist, and one with the rare ability to not only write and illustrate children’s books with a wonderful range of sensibilities, (and is the epitome of not talking down to kids, for sure) but has also created a huge body of hard-hitting work for adults, powerfully addressing social and political issues head on. He had a brutally sardonic sense of humor, his work still packs a punch. And always masterful drawing. A true original, and incredibly prolific over his long life. Among his picture books , my favorites are Crictor, No Kiss for Mother, The Hat, and The Three Robbers.

Choosing words. I’ve always felt that if, in my books, a young reader doesn’t know a word, they can ask a caregiver, teacher or older sibling what it means. That’s how we learn, right? With that in mind I try not to limit the language I use, but with a sense of limits, the audience, and appropriateness.

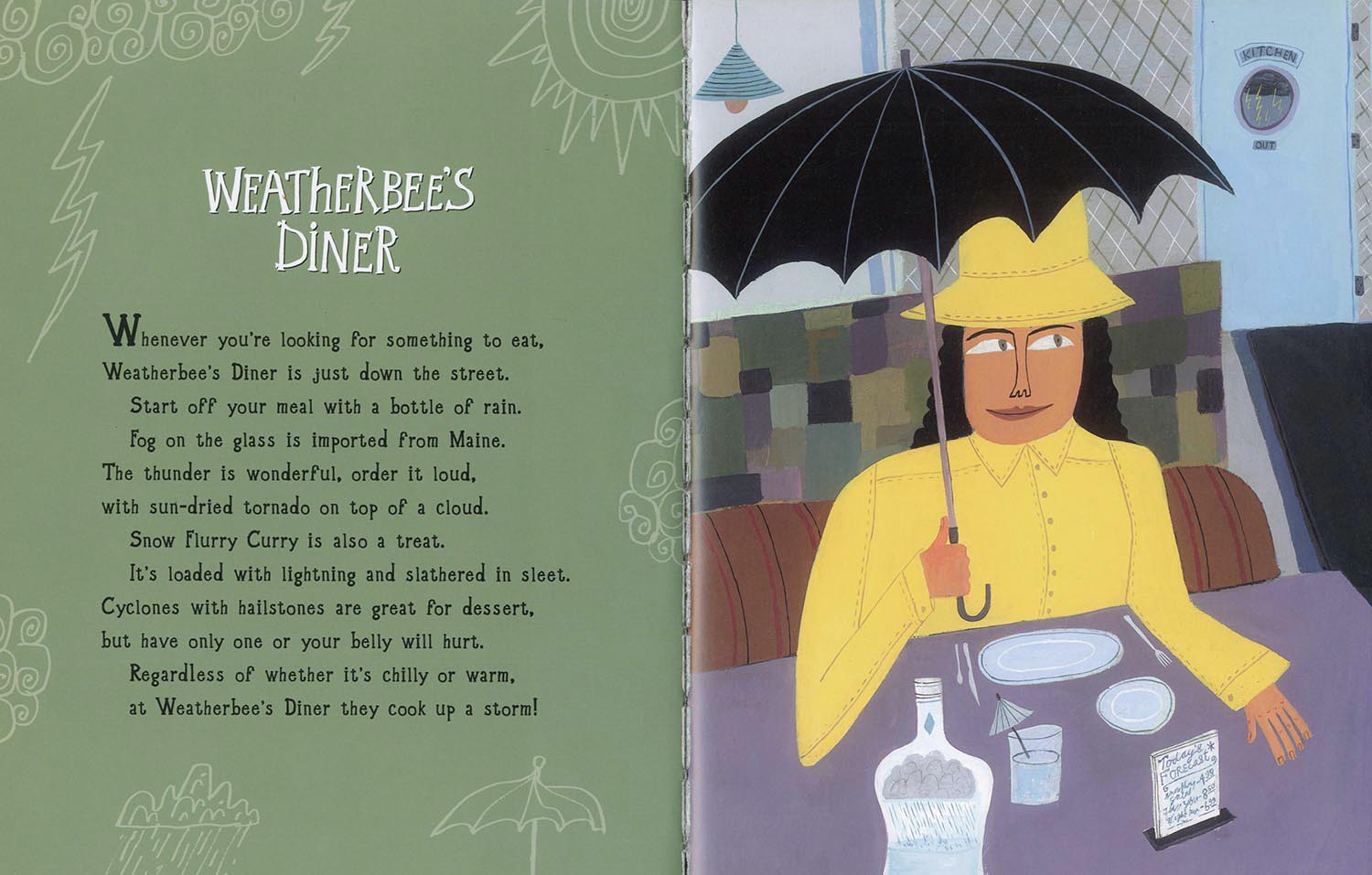

So, in my first book the title poem contains “jury duty” because I liked the near-rhyme with “flying fury.” Also, I liked the idea that kids might hear “doody,” which is funny. A six or seven-year-old may not know what jury duty is, but can ask. A little civics lesson built in. A poem called Weatherbee’s Diner has the word “slathered” which a young kid may not know, but when they ask, I think they’ll remember it, and use it. It sounds like what it means. A fun word.

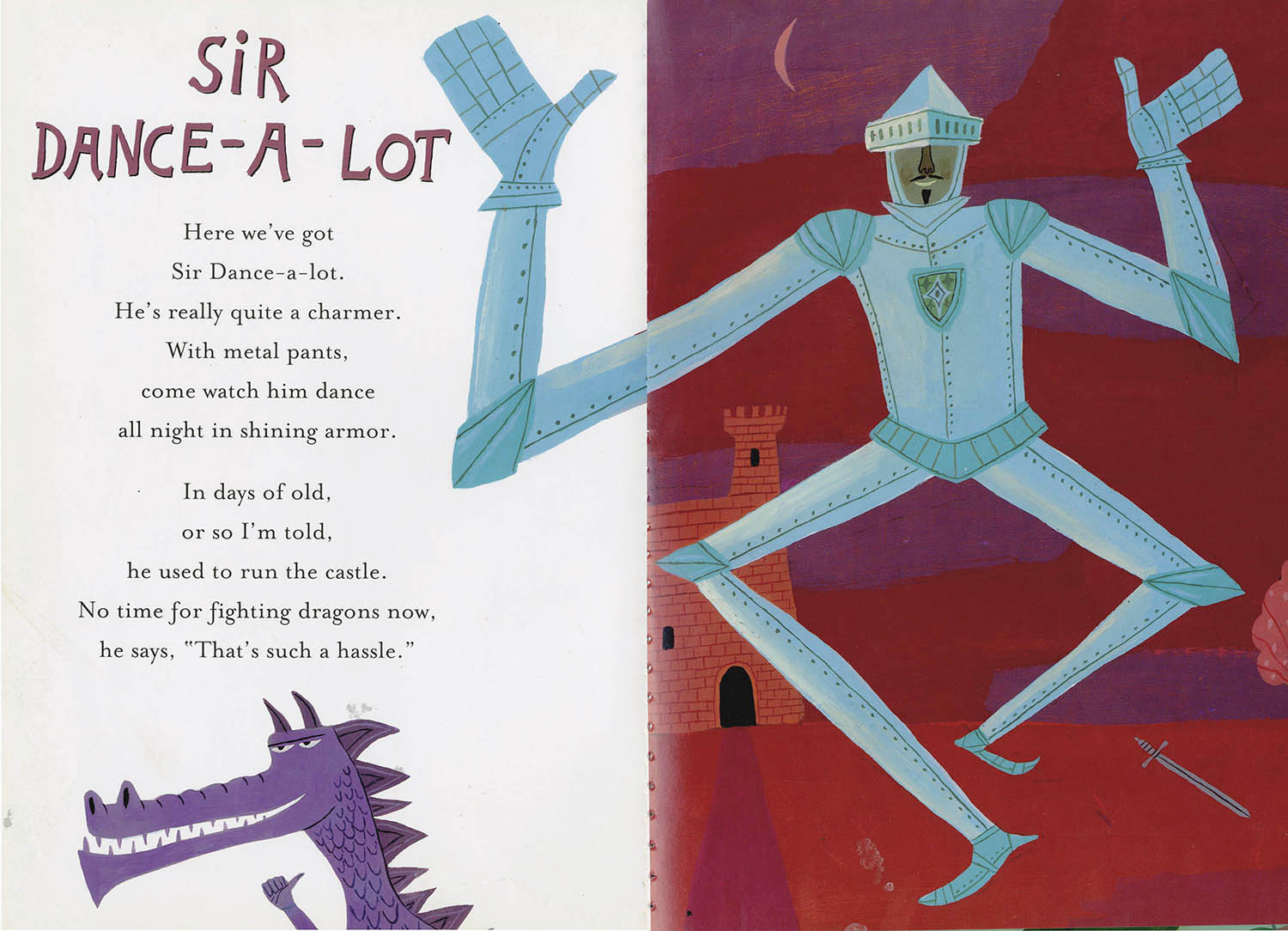

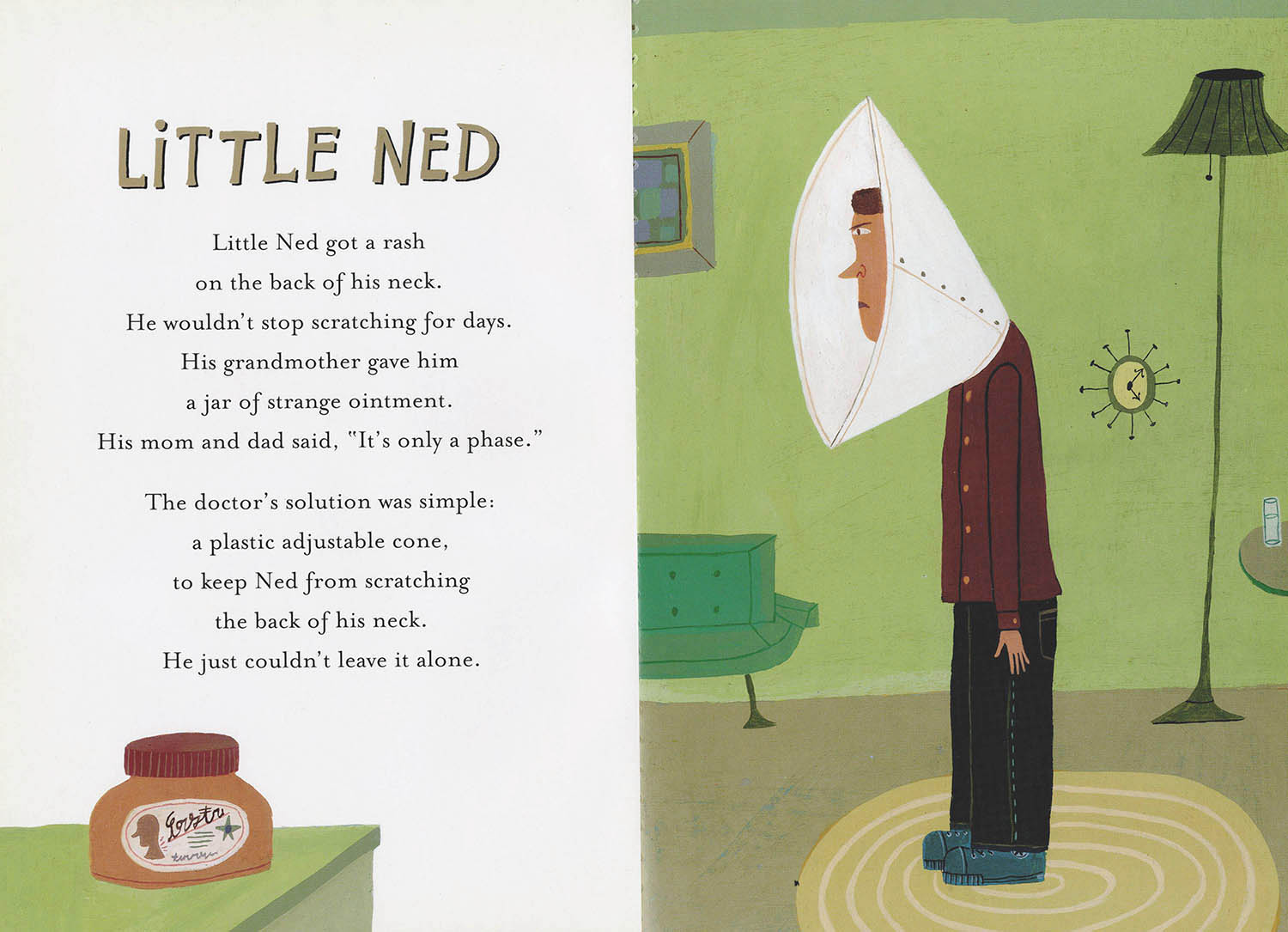

And my second book has the words “hassle” and “ointment.” Again, a kid that age may not know what they mean, but they’re fun to say and they can inquire. And as I mentioned before, I have two books aimed at middle-grades and above, so for those there’s a different metric for appropriate language and vocabulary.

Calef Brown is a New York Times best selling author and illustrator of thirteen picture books, including Polkabats and Octopus Slacks, Flamingos on the Roof – Winner of a Myra Cohn Livingston Award, Hypnotize a Tiger – Winner of a Lee Bennett Hopkins Honor Award, and most recently, Up Verses Down. Kirkus Reviews called him “A modern master of nonsense verse”. He has also illustrated the work of a variety of authors, including James Thurber, Daniel Pinkwater, Edward Lear, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Brown’s illustrations have also appeared in Time, Newsweek, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and many other publications. See more of his work at calefbooks.com.