In the U.S. recently, we have been making a horrific attempt to rewrite our history through a racist and white supremacist lens. In our ignorance, fear, and hatred, we are erasing the facts and testaments of the conflicted and often tragic story of our nation from our schools and museums. In erasing all the bad, we also erase all the good — the small steps towards justice, however halting, however often stumbling backwards. Left with nothing but ignorance, we can only proceed forward in fear, without hope. Because when we erase the past, we negate the future as well.

And we’re trying to spread our belligerent ignorance to the rest of the world, too, we are shamelessly trying to rewrite the history and reframe the actions of leaders in the rest of the world as well. If the goal is to leave us so ignorant, hopeless, and upset that we can’t recognize what is going on around us and take steps to change it, I can’t believe it will work. Memory is too powerful. The human desire to share stories and concerns, to support each other, and to work for a better future is too powerful. And one of the irrepressible ways we have to share our stories is through music.

In the wonderful essay “Freedom Songs: The Role of Music in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle by Dr Gavin Brown, he speaks about the way in which the role of music in black South African society translated into its becoming a powerful tool in its political culture. “Songs communicate shared social and political problems and a commitment to change in ways that political speeches and articles do not.” He explains how the songs developed from a variety of influences and evolved over time to become songs of protest, reflecting specific events along the way:

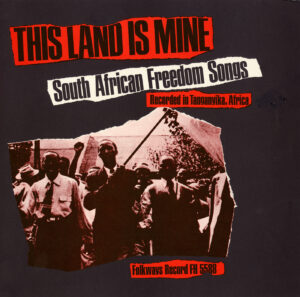

Many freedom songs have their stylistic origins in makwaya (choir), a popular style of choral music that combines southern African singing traditions with the form of Christian hymns imported from Europe. Hymns and work songs were often reworked and given new meanings for the anti-apartheid struggle.

This musical form often used short slogans, either in indigenous languages such as isiZulu and isiXhosa or English, repeated over and over in a ‘call and response’ style, over simple melodies. While some of these songs have identifiable composers, most were created and sung collectively, changing over time.

As well as adapting existing hymns and songs that had meaning for people, new songs were written that responded to events in South Africa. These anti-apartheid ‘freedom songs’ celebrated political victories, assert defiance against apartheid, and mourned those who were killed by the police and army for opposing apartheid. The songs from the liberation struggle are a historical record of the South African people’s resistance to apartheid. Collective choral singing created common bonds – not only did multiple voices combine, but the act of singing political songs together helped unite the singers. Such was the power of collective singing during the apartheid era that many of these songs were censored or banned by the South African authorities.

I genuinely believe that one of the most important human rights is the freedom to live an ordinary life, to go about the daily tasks and concerns that connect all humans, and to do so without dread or fear. As simple as this might seem, it’s something that’s not possible under apartheid. So it’s no surprise that many of the songs that became protest songs described activities or reflected rhythms and melodies of day-to-day life under apartheid. They might mimic the sounds of the trains that took people to work each day, or took them from their homes to the city in a search for employment. And there are songs describing what life was like for women under apartheid, when often their only opportunity for employment was as a servant to a white family.

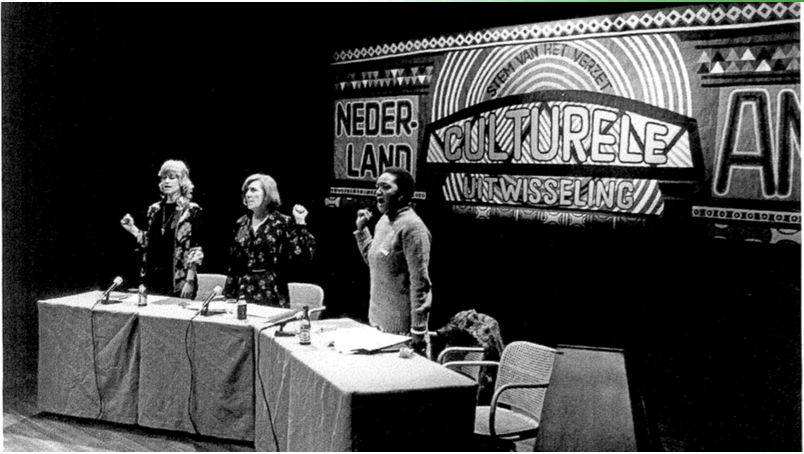

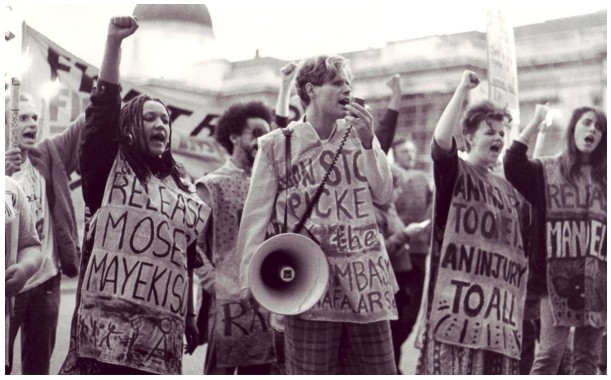

Dr. Brown writes of the myriad ways the ANC used music to create a culture of resistance and to fight for freedom from the 1950s through the tumultuous decades that followed. In 1960, police fired on anti-apartheid protesters, killing 69 of them, arresting thousands of activists, and banning public protests. Songs became a powerful tool of communication for protesters forced underground, as well as an expression of their sadness and anger. In the 1970s, the ANC set up two cultural groups designed to share anti-apartheid poetry and songs: the Mayibuye Culture Ensemble, which was based in London, and the Amandala Cultural Ensemble, based in the ANC camps in Southern Africa.

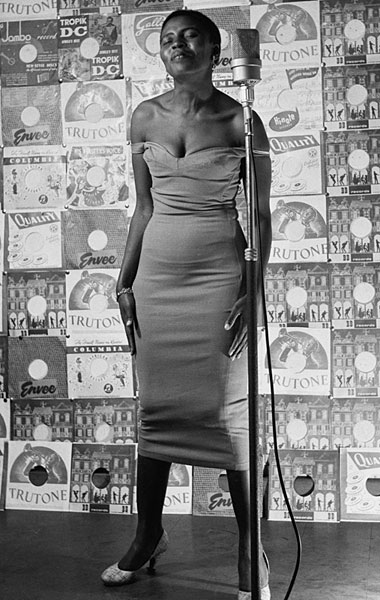

The ANC also made secret radio broadcasts from around South Africa. “By the 1970s, the ANC’s Radio Freedom was a much larger operation broadcasting from five African countries. As well as political speeches and news, Radio Freedom played anti-apartheid music for its listeners in South Africa. Given that the South African government banned music by anti-apartheid musicians like Abdullah Ibrahim and Miriam Makeba, this was one of the few ways ordinary South Africans could listen to their music.” If you were caught listening to Radio Freedom, you could go to jail, but the songs played there were “soon sung by people in the streets and townships of South Africa,” spreading them to everyone.

“If some of the songs from the 1960s were mournful laments about the violence of apartheid, and songs from the 1970s sought to encourage a new sense of ‘black consciousness’, in the 1980s many of the most popular freedom songs captured a sense that the Black majority in South Africa were engaged in a ‘people’s war’ against apartheid.”

By the 1980s, the movement had grown and captured the attention of people around the world, including artists like Madness, Peter Gabriel, and The Specials. As Dr. Brown explains, with this growth and the support of hundreds of thousands of people internationally came confidence, and with that confidence, the songs became more militant. “If some of the songs from the 1960s were mournful laments about the violence of apartheid, and songs from the 1970s sought to encourage a new sense of ‘black consciousness’, in the 1980s many of the most popular freedom songs captured a sense that the Black majority in South Africa were engaged in a ‘people’s war’ against apartheid.”

One song that became an anthem of the anti-apartheid movement was Nkosi Sikelel’i Afrika (God bless Africa), written by Enoch Sontonga in 1897, which was often sung to open and close political rallies.

Hugh Masekela’s Stimela and the song Shosholoza mimicked the sounds of a train, which Masekela describes as the symbol of something that took away your loved ones.

The song Shona Malanga spoke about the freedom domestic workers enjoyed on their day off and eventually the lyrics changed to describe secret anti-apartheid political meetings.

Malibongwe was transformed from a Christian hymn into a song celebrating women’s role in the anti-apartheid movement.

Thina Siswe is a song with no known author and shifting lyrics, mourning the dispossession of the African people from their land by European colonists.

Bahleli Bonke Etilongweni, by Miriam Makaba translates to “our leaders are in jail.”

Vuyisili Mini was a trade union organizer, member of Siswe, the armed wing of the ANC and South African Communist Party, hanged to death after being charged with acts of sabotage and involvement with the killing of a police informer. He went to the gallows singing liberation songs.

Somlandela (we will follow) was a gospel song with lyrics altered to become an anti-apartheid anthem.

Nants’ indod’e emnyama was a taunting song that challenged the authority of supporters of apartheid.

Amajoni (soldiers) calls for people to become soldiers for the anti-apartheid struggle.

Sezenina (what have we done?) became popularised after the school students’ uprising in June of 1976.

E Rile was a song with a militant message released in 1978

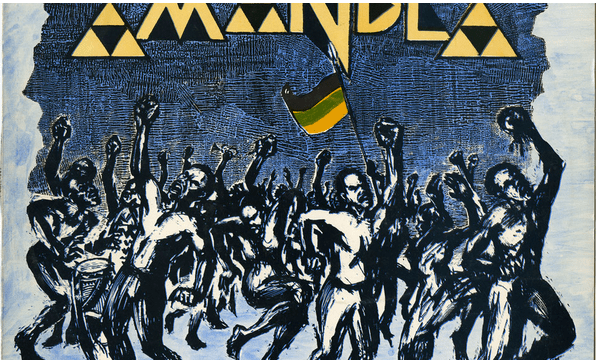

Rohilahla Mandela was a call-and-response song. Rohilahla, Nelson Mandela’s birth name, means ‘pulling the branch from a tree’ in isiXhosa, which loosely translates to ‘troublemaker.”

Read Dr. Gavin Brown’s Freedom Songs: the role of music in the anti-apartheid struggle Part A and Part B on the Anti-Apartheid Legacy website.

Categories: featured, Magpie Mix Tape, music