By Mike Ladd

Our walk into El Greco’s View of Toledo begins at dawn on the tenth floor of a modular hotel in Madrid. Parting the curtains, I check the eastern horizon.

Spokes of bright sunlight

Through morning cumulus clouds

El Greco heaven

In the apartment block opposite, a diminutive figure smokes at his open window, using his spare hand to fan the fumes out from his room. At first, I thought he was signalling to me: ‘Look at this sunrise, just like the master would have painted!’ The man even resembles one of the figures in View of Toledo, no bigger than a termite, the sunrays gleaming on his head and thorax. My partner Cath and I pick up our backpacks and hurry down to the Metro.

In the underworld

Fellow travellers swaying

Hands grip yellow poles

Close up, on the pole next to me, I note the fine blue veins in the delicate, elongated hand of a young woman. She has white, almost translucent skin — like an El Greco saint. This underground carriage reminds me of Aldous Huxley’s comment that in El Greco’s later paintings ‘every personage is a Jonah’ swallowed, looking out from inside the viscera of the whale.

At Atocha station we transfer to a sleek, snake-headed train, Alto Velocidad, to Toledo. It departs to the computerised second and soon reaches 300 kilometres per hour. We slip past olive groves, electricity sub stations, outer suburban developments taking over from old haciendas.

Hay fields, maize, limestone,

La Mancha reduced by speed

Blurs of spring poppies

Domenikos Theotokopoulos who became known by his nickname El Greco (The Greek) was born circa 1542 in Fodele village, northwest of Heraklion, Crete. He came from a family of businessmen and functionaries working for the Republic of Venice, which at that time ruled the island. Domenikos trained as an icon painter, making glowing images of saints and virgins on wooden boards with backgrounds of gold. Though he worked in the Byzantine tradition, you can already see the beginnings of his mannerist style in those illuminated figures. Restless, ambitious and desperate to discover more about art than the island of Crete could provide, at the age of twenty-five he moved to Venice and never came back.

Dark water shadows

City of whispers and spies

A new world shimmers

In Venice, El Greco started painting on canvas, opening his perspectives to the marvellous architecture of his new location and adopting the colours of Titian and Veronese. But Venetian society was labyrinthine and secretive. Its machinations confounded him. He was unable to break into the circles of influence that he needed, so, in 1570, he moved to Rome, hoping to find the patronage that had eluded him.

In Rome, at that time, new villas were being built in the imperial ruins, and grapevines grew over the crumbling city walls. Even though the puritanical Pope Pius V ruled, there was more freedom than in Venice. El Greco was supported by the art patron Cardinal Farnese and was allowed to live in an attic in the cardinal’s new, unfinished Palazzo. Later El Greco was evicted from his room and forced to find other accommodation. Why he was thrown out we don’t know, but he was not a diplomatic man. Proud and argumentative, he often created enemies.

People of the past can seem monsters to us — how could they live with slavery, colonialism, public execution? But perhaps we in our turn will seem monstrous to the future. How could we use missiles against unarmed civilians, choke the planet with pollution and drive other species to extinction?

There is an old story that at this time El Greco offered to repaint the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. By then Michelangelo had died, and the new hierarchy of the Vatican decided some of the figures in his Last Judgement were far too fleshy, particularly the nudity of the saints and angels. The damned being dragged to hell could show a few genitals, that was the least of their worries, but not the elect. These swirling, heavily muscled bodies inspired by Michelangelo’s love of Dante’s Divine Comedy were too dramatic and shocking. The Vatican had already commissioned Michelangelo’s student Da Volterra to paint over vital parts of some nudes with oddly suspended bits of drapery and to cover the full-frontal St Catherine with a green dress. But El Greco offered to re-do the entire wall. If the story is true, what are we to make of it today? Outrageous opportunism? Overwhelming ego? Or desperation? It’s dangerous to read motivation into four-hundred-year-old tales. People of the past can seem monsters to us — how could they live with slavery, colonialism, public execution? But perhaps we in our turn will seem monstrous to the future. How could we use missiles against unarmed civilians, choke the planet with pollution and drive other species to extinction? What monsters!

We know a little about El Greco’s personality from notes he made in the margins of two books he owned: Vasari’s Lives and Vitruvius’s De architectura. These notes reveal El Greco’s often sour opinions of other artists. For example, while he admired Michelangelo’s sculpture and architecture, he was dismissive of his painting, particularly of the human form. This seems a bit rich when we consider El Greco’s own extreme mannerism.

Stretched hands and necks

Bodies twisted and floating

His people are flames

Was his suggestion to repaint the Sistine Chapel a serious offer, or just another of his brash comments? The tale concludes that El Greco’s effrontery made him so despised by the painters of Rome and the friends of the late Michelangelo, he was driven out of the city. In 1577 he left for Spain and settled in Toledo, which became his home for the rest of his life.

Tagus by the tracks

A green thread pulled in and out

By the speeding train

Ten kilometres from town we get our first glimpse of the imposing cube of the Alcazar fort, standing on top of Toledo hill. In the train carriage the red digits showing our velocity slip backwards; the landscape slows and halts. From the station we walk past panel beaters, La Rosa tile factory, then up the hill by the river — and there it is, El Greco’s view of Toledo, on first glance hardly changed in over four hundred years. I hold up my only map to this place, an A4 colour photo of the painting, and try to orientate it to the Alcántara bridge as we approach from the east.

Over verdant hills

An apocalypse coming

City bleached white

Rainer Maria Rilke writes of his awe at the light in the picture, describing it as ‘in tatters’ and ‘ripping’ into the ground. He says ‘the startled and affrighted city rises in a last effort as though to pierce the anguish of the atmosphere. One should have dreams like that.’

The bottom third of El Greco’s painting of Toledo is dominated by the greens and browns of meadows and river; the middle third is the sepulchral city, spot-lit in intense white light; the upper third is all inky blues and blacks of a threatening storm. The deepest, blackest parts are right behind the blue-white city, as though Toledo was about to be hit by a tsunami. It’s high visual drama and it’s hard to believe View of Toledo was made sometime between 1597 and 1599. It looks post-impressionist, as though it was painted early in the twentieth century. In 1908, in a letter to sculptor Auguste Rodin, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke writes of his awe at the light in the picture, describing it as ‘in tatters’ and ‘ripping’ into the ground. He says ‘the startled and affrighted city rises in a last effort as though to pierce the anguish of the atmosphere. One should have dreams like that.’

When he painted his View, El Greco had been living in Toledo for twenty years and was well-established, though not exactly popular. He had shown his originality from the day of his arrival, causing equal amounts of jealousy, admiration and dislike among the local artists. El Greco’s reputation as a difficult man was underlined by his constant haggling and lawsuits over payment for his portraits and altarpieces. He lived in the working-class area of Santo Tomé, renting rooms in the ramshackle apartments of the Marquis of Villena. By then, his son Jorge Manuel was painting beside him in the family studio. The boy’s mother was Doña Jeronima de las Cuevas, though El Greco did not acknowledge her as his wife. We don’t know why, but there is speculation that he may have left a wife behind in Crete.

Landscapes were unusual for El Greco (only two survive) and when he did produce them, they certainly couldn’t be described as topographic. I move my photograph of View of Toledo from left to right, glancing back and forth to the landscape it portrays, and I begin to see how he’s shifted things. In El Greco’s picture, the island where a man appears to be watering a horse is on the wrong side of the Alcántara bridge, as is the weir and the watermill. The river itself should flow out to the left of the painting, but for compositional reasons, El Greco bends it back around to the right. In reality, the cathedral can’t be seen from here, but in the picture it’s been put to the left of the Alcazar fort. We’re standing in the centre left of the painting, at the point where El Greco shows tiny figures (ant-like in their insignificance) struggling up a steep incline to the eastern tower of the bridge. He distorts the landscape for pictorial excitement. In real life, the plunge down into the Tagus is not nearly so dramatic.

The river, which surrounds the town like a deep-walled moat, is olive green in the sunlight; no storm clouds over Toledo today — only the mild blue of a spring sky. Poppies and cornflowers grow in the rock fissures. Concentric circles radiate out from points where fish break the surface of the water and occasionally there’s a larger splash. A heron watches from the low branches of a mimosa. Weeds and wild figs grow out of the base of the bridge. The current flows from right to left, casting rippled shadows under the arch, and the curved space is congested with tiny black-and-white swallows who build mud nests which hang down like grape clusters. There’s a constant wittering chatter punctuated by the plaintive call of an unknown bird. A visit by a glossy nest-robbing crow causes a panic of swallows, the tracery of an explosion in the air. Distant traffic and the clink of someone working stone are the only other sounds.

Two nuns cross the bridge

White robes and black headdresses

Colour of swallows

Before going over the Alcántara bridge into the old city, we decide to explore more of the left-hand side of the painting and climb up the road to the castle of San Servando.

Lavender and pine

In the shadow of the castle

two cats watching

The castle, with its archetypal round towers and crenelations, is now a youth hostel, but there’s no-one about today. At the base of the fort, there’s a loquat tree with ripe fruit. The loquats are sweetly acidic and thirst-quenching, and we eat a handful. San Servando is a chronicle in stone of the alternating rulers of this corner of the world: Christian and Muslim, monastery and fortress, ruin and restoration, back and forth over the centuries. The way it looks today is much as El Greco painted it.

El Greco’s self-portrait from 1595, made only a few years before he painted View of Toledo, shows a gnomish figure with a short spade of beard poking over a white ruff. He looks much older than his fifty-three years. He has a high-domed balding head, pinched cheeks and deep-sunk, beady black eyes that have a knowing, careworn expression, mistrustful and sad. But perhaps I’m projecting into his gaze some of the things that were said about him: ‘a solitary’, ‘outspoken’, ‘temperamental’, ‘superior’, ‘litigious’, ‘austere’, ‘stand-offish.’

Self-portrait in cold light

Black cloak trimmed with fur

Deep winter

This is the face that appeared to the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis in a dream. In his Report to Greco, he imagines the painter telling him ‘reach what you can’, then, ‘reach what you cannot.’

This is the face that appeared to the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis in a dream. In his Report to Greco, he imagines the painter telling him ‘reach what you can’, then, ‘reach what you cannot.’ Kazantzakis remembers El Greco’s ‘Toledo in the Storm’ and sees in it a battle between light and darkness, and summoning that image, asks the painter to be the judge of his life.

Coming back down to the river, we cross the Alcántara bridge into the city. The doors in the gateway are studded with iron flowers. The bridge itself is vertiginous; I look nervously over the low wall, squinting at the long plummet into the cloudy green Tagus below. On the western side of the bridge, we go through the Moorish keyhole entrance to the old city and begin climbing up the stairways and streets that follow the central white diagonal of the El Greco painting. We pass the Museo Santa Cruz where crowds of people line up to see the exhibition marking 400 years since El Greco’s death, then on through the Plaza Zocodover to the Cathedral with its ugly altarpiece.

Stacked like warehouse shelves

Saints and holy families

Footsteps hollow sound

Cath and I reach the building at the top right of the View of Toledo, the Alcazar fort, that to me still reeks of militarism, colonialism and fascism.

Cath and I reach the building at the top right of the View of Toledo, the Alcazar fort, that to me still reeks of militarism, colonialism and fascism. Here Charles the First of Spain congratulated Cortez on his return from destroying the Aztecs and seizing their lands, here Franco’s supporters were besieged during the civil war, and here after their victory, Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, visited as part of a propaganda exercise. He was meeting Jose Moscardó Ituarte, the commander of the Nationalist garrison, who sacrificed his own son in the siege. The Republicans had captured the son and said they would execute him if his father didn’t surrender. General Moscardó replied by telling his boy to ‘die like a patriot’, and later the boy was indeed executed by the Republicans. The Alcazar was virtually destroyed during the war but has been restored. In El Greco’s painting the corner battlements are flat-topped, but today they are surmounted by black spires.

We come back downhill to explore more of the central gorge. Crossing the Alcántara bridge again we clamber down the rocky slope on the left bank of the Tagus to where (reversed in the painting) El Greco shows tiny stick figures washing clothes and fishing.

White water cascade

Fat salmon leaping upstream

Ripe mulberries

Today at the weir there’s a wonderful sight, muscular salmon launch their long bodies out of the water and succeed in getting over the lip. Entranced, we watch as salmon after salmon makes the leap. Close to the weir Cath finds a mulberry tree and we stop to harvest some of its luscious crimson. I fantasise that with all these fish and fruits you could live by foraging here in this painting.

Aphids in the grass

Feathery seeds stick to legs

Spring’s invitation

On a modern bridge we cross to the other side of the river and stop at a picnic ground overgrown with daisies and thistles. The white daisies have yellow centres and in each one a dark brown beetle is pollinating the flower. Spring. Everything here is procreating, seeking continuance.

Out of her pack Cath takes a wedge of brie, a dark red tomato, and a pebbly-skinned cucumber and I tear apart a baguette for our shared lunch. Dessert is fresh mulberries, our fingers still purple-tipped from the picking. Berry juice stains the pages of my notebook as I scribble. I am so much happier here in this overgrown, neglected park, than with the crowds in the cathedral, the Alcazar or the Museo. Is it something about me to seek the margins, not the middle of any situation?

El Greco sought the centre, wanting the recognition and prestige of the court and religious hierarchy, but he was too much of an individualist to ever become an official painter. While he maintained his business in Toledo for thirty-eight years through private portrait commissions and altarpieces for churches, he failed to win wider royal approval. Phillip II, the most important art patron in Spain and perhaps all of Europe at the time, decided El Greco’s stormy backgrounds and eerily front-lit subjects were too weird for his taste.

He produced paintings of the numinous and supernatural, in swirls of colour and light, not standard votive imagery.

The cantankerous Greek broke with traditional compositions, taking an off-centre, lateral or radically foreshortened view. He put Biblical characters in contemporary dress. He used models from the madhouse for his saints. He dramatised. He put his art above depicting merely what he was asked to depict, and so remained the independent outsider, not the diligent servant. He produced paintings of the numinous and supernatural, in swirls of colour and light, not standard votive imagery.

Beware of landslides!

Swastika drawn on a sign

By the sheer-walled gorge

Lunch over, we walk along the top of the gorge walls, further into the back of the El Greco painting. On a sign by the precipice, ‘Peligro Desprendimientos’, someone has graffitied a Nazi symbol, but then a sticker has been put over the top of the swastika. It proclaims ‘Skinheads Antiracistas Castilia’ with a symbol of a Trojan helmet on a castle. Anti-racist skinheads. Interesting.

After the Global Financial Crisis, unemployment in Spain reached twenty-five percent and closer to fifty percent for youth. Under these conditions nationalism and racism can metastasize, with migrants blamed for lost jobs and resented for receiving welfare. There have been some attacks on mosques and North African migrants, and the formation of extreme Nationalist parties, such as España 2000, which has a branch in Toledo. Their campaign advertisement shows people raising their hands in front of their bodies in a stopping motion. A little higher and it would look just like a fascist salute.

The old dictator

Paints hunting scenes to relax

Stillness of dead birds.

There has been a deliberate erasure of the Civil War in Spain. After the death of Franco, King Juan Carlos declared an amnesty that made it illegal to investigate the crimes committed by both sides during the war, as well as the later crimes carried out by the Franco regime. This collective (some claim protective) amnesia prevails still, as the country alternates between right-wing and socialist governments. Franco’s grandson now promotes his grandfather as a talented, misunderstood painter of still lives. Sites of mass-killings, such as the execution wall at Paterna, where thousands of Republican prisoners were gunned down in batches of 50 at a time, have only recently been excavated to try to identify bodies and return them to relatives.

Toledo has had a long history of both tolerance and intolerance. A centre of learning and a translation hub for texts by Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars, it was at other times the site of public executions, burnings, forced conversions and expulsions. In 1582, El Greco was a translator at a trial conducted by the Inquisition. A young Athenian was accused of heresy, and El Greco interpreted for him in Greek. The young man was finally acquitted, but not before spending ten months in jail during the course of the terrifying trial in which the prosecution threatened him with torture and the slow death sentence of ten years in the galleys.

Strange light on the town

Tomb-like cathedral and fort

The fairytale green

Brian A. Oard in his essay City on a Hill: El Greco, View of Toledo sees the threatening clouds, and the dominance of the Cathedral and the Alcazar (church and state, respectively) as representing a totalitarian city of the Inquisition. Oard goes as far as to say the painting depicts a city that has been ‘ethnically cleansed’ of Jews and Muslims; that its greyish white purity symbolises a ruthlessly enforced Christian orthodoxy.

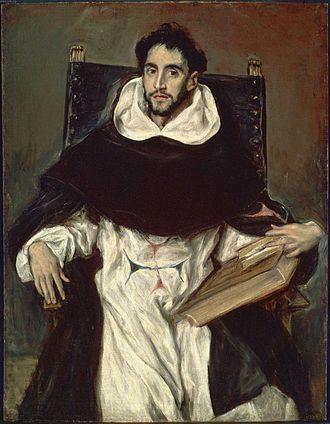

I think El Greco’s choice of lighting is far more about creating pictorial drama than an allegory of the Inquisition. It’s true he was an outsider, but it’s hard to characterise him as a critic of the church when almost all his work came from his religious connections. Only a year after he finished painting View of Toledo, El Greco made one of his greatest portraits – that of Cardinal Don Fernando Niño de Guevara, the Grand Inquisitor himself. If El Greco was subtly rebelling against the Inquisition, he was doing so dangerously close to the very heart of it.

Gold patterned wall

Carmine and silver costume

Inquisitor’s black glasses

In El Greco’s portrait, the Grand Inquisitor sits in front of a starkly divided background, a luscious gold wall on the right, plain dark wood on the left. The cardinal seems to hover above the marble floor, resplendent in silvery white surplice, carmine cape and barrette, staring penetratingly at us through the latest technology – a pair of black spectacles, the all-seeing eyes of the Inquisition. One claw-like hand clutches the arm of the chair, the other relaxed, limp and long-fingered with jewels. The stark contrasts in this painting remind me of the insignia of the Inquisition itself; on one hand the olive branch of peace, on the other side the sword — the cross in the middle the only way to gain one or avoid the other.

Down by the river

Cool mustiness of wild figs

Sunlit eucalypts

We continue beside the Tagus. The path here is a section of the Camino Natural del Tajo, a walking trail that runs from Montalban to Aranjuez. Emerging from the deep shade of a fig grove into the sunshine, we’re confronted by a stand of gum trees, the scent of eucalyptus like a surprise from Australia. Above the stump of a Roman aqueduct, rock climbers cling to the walls of the gorge. Around the next bend we meet a fisherman with all the latest gear, his fancy stands and friction reels such a long way from the figures with sticks in the El Greco painting.

At the Ponte San Martin we climb back up the gorge walls into the old Jewish quarter of the town, walking in the quiet of late afternoon along San Juan de los Reyes, past the monastery, into Calle Reyes Catolicos, and past the synagogue. At Plaza Barrio Neuvo Cath and I stop for a Campari and ice in the shade. A little further along, opposite the Jardines del Transito, is where El Greco lived, though his house is no longer there. A shop selling ice cream now occupies roughly the same position.

Jumble of paintings

Heavy, leather-bound volumes

His empty shoes

By the end of his life El Greco was struggling to pay his bills. He seemed to spend everything he earned on materials, books, and lawyers. A protracted legal dispute over his fee for a retablo had put him into debt, a financial position from which he and his son never fully recovered. An inventory of El Greco’s possessions made after his death shows (naturally enough) his large number of paintings, but also a sizable collection of books in Greek, Italian and Spanish, something of a luxury at that time. He didn’t spend a lot on fashion though; the same inventory shows only four shirts, two capes, one doublet, and four pairs of shoes.

Rainbow on the tomb

Still fighting about money

Artist’s bones vanish

Even as a dead man El Greco was the centre of disputes. In 1614 he was buried in the crypt of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, but due to a wrangle about the price of his monument, his remains were later moved to the new family vault in San Torcuato. This church was later demolished, and El Greco’s bones disappeared with it. His last painting was the rainbow-hued chiaroscuro The Adoration of the Shepherds, which he made to decorate his own tomb. Jorge Manuel kept the studio going after his father’s death, but less and less successfully. Jorge died in 1631, leaving his wife and children in poverty.

El Greco’s art was highly valued after his death, in particular by the famous poet Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, whose stunning portrait he had painted, but thereafter his style fell out of fashion for nearly three hundred years, until it was embraced by painters such as Cézanne and Picasso. Today in Toledo his name is everywhere: the El Greco Museum, El Greco hotel, El Greco restaurant, even El Greco beer.

Toledo sunset

No restaurants open yet

Finally, a sign

It’s too early for dinner in Spain, but we’re hungry after a long day walking around Toledo, and eventually we find a Posada with an open sign near the Mosque of Cristo de la Luz. We eat a very good meal of falafel, hummus and tabouleh. The restaurant owner is a migrant from Syria. He saw the disaster coming and got out years before the civil war. There’s too much food and we ask to take the rest away with us. He’s out of plastic containers, so comes back with the actual plates we’ve been eating from, wrapped up in tinfoil. We protest that we can’t take his crockery, but he insists. Clanking slightly, Cath and I walk back over the Alcántara bridge, exiting on the left of View of Toledo to catch the last train back to Madrid.

Sources:

El Greco, Michael Scholz-Hansel, Taschen, 2004

El Greco Life and Work – A New History, Fernando Maraís, Thames and Hudson, 2013

‘El Greco’, Aldous Huxley, Life, 24 April 1950

Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke 1892-1910, trans Jane Bannard Greene and M.D. Herter Norton, WW Norton Company Inc, 1945

‘City on a Hill: El Greco, View of Toledo’, Brian A. Oard, Beauty and Terror: Essays on the Power of Painting, 2009

Report to Greco, Nikos Kazantzakis, Faber and Faber, 1973

Mike Ladd is a South Australian poet, essayist and nature lover. He has published ten collections of poetry and prose, including the natural history Karrawirra Parri, Walking the Torrens from Source to Sea, from Wakefield Press. His most recent book is Dream Tetras (2022) an experimental collaboration with visual artist Cathy Brooks. Mike was the editor of ABC Radio National’s Poetica program, which ran for eighteen years and brought Australian and international poetry to a wide audience. His New and Selected Poems is due out from Wakefield Press in 2025.