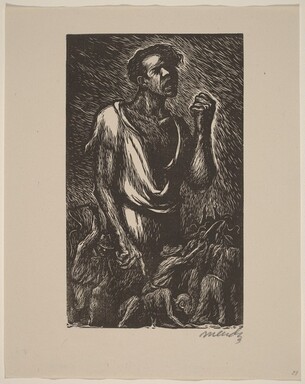

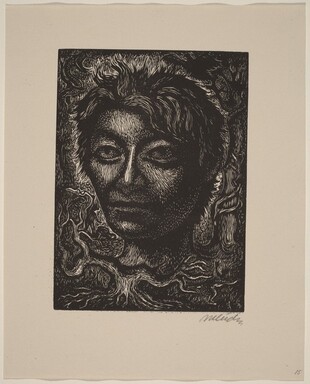

Leopoldo Méndez lived from 1902 to 1969, and his life and career spanned monumental events in the history of Mexico and the world. He saw world wars, revolution, changes in government and ideology, and the terrifying rise of fascism. Throughout it all he remained steadfast in his fight for justice for the oppressed and in his mission to bring art and education to everyone in Mexico in pursuit of a stronger nation and a better life for all.

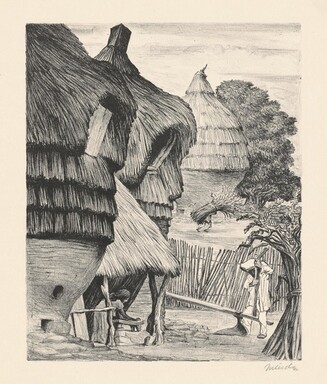

Méndez was born into poverty, one of eight children, the son of a shoemaker and a farmworker of indigenous descent. Both parents died while he was a baby. He was forever influenced by early memories of his family and neighbors struggling to make a living and survive. He studied art in school and eventually served as an art teacher in the public schools that were established after the revolution. At this time the new socialist government was committed to providing public education and public libraries to everyone throughout Mexico, including in historically underserved rural communities. And art was an important part of the education that they wanted to provide access to. They set up plein air schools throughout the country, teaching mainly mainstream European methods. They believed that a better-educated, better-informed, more skilled populace would better be able to perform the functions necessary to maintain a happy and liveable society.

Throughout the years following the revolution, artists would band and disband in various groups and organizations. They would write manifestos and lists of demands and ideals and hopes for the future and for the ways that they, as artists and activists, could help to shape it. Throughout the years, despite the many disagreements the artists had with each other and with the government, for the most part, they maintained the common goal of bringing art to as many people as possible. This began, famously, with murals. Apparently, Méndez approached Diego Rivera with a small painting as a sort of audition to become a muralist, but Rivera took one look at it and set it aside. Though Méndez was involved in painting murals throughout his career, he eventually took exception to the idea that the murals were painted in grand “important” buildings that common people didn’t have access to. He turned towards printmaking and puppetry as his chosen methods to reach the most people.

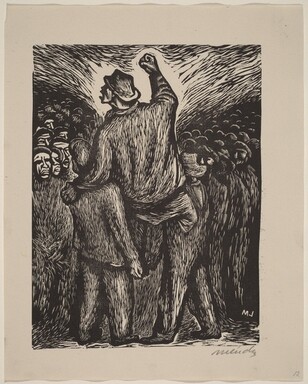

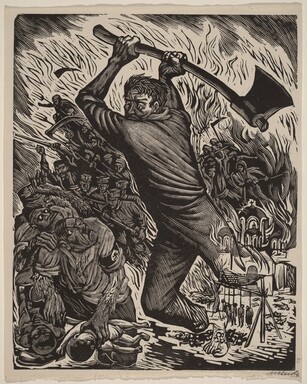

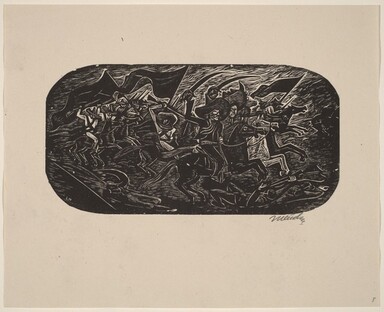

From 1921 to 1927, Méndez was a founding and continuing member of the Stridentist Movement (Movimiento Estridentista). Whereas earlier movements had been approved and supported by the government, the Stridentist movement was independent, irreverent, revolutionary, and hopeful. He expressed their credo thus, “The urgency of expressing the feelings of a free people, to put their spiritual yearnings at the service of the Revolution, made the painters abandon the concept of art for art’s sake, though that at least required or permitted artistic work to be refined until perfected, in exchange for a momentary work, without careful outlines, but in the end this has created a new aesthetic, one of protest, full of popular longings, and that lives in the full multitude of rebellion, is strong and great and captures us with the emotion of battle — this is life.”

“The urgency of expressing the feelings of a free people, to put their spiritual yearnings at the service of the Revolution, made the painters abandon the concept of art for art’s sake, though that at least required or permitted artistic work to be refined until perfected, in exchange for a momentary work, without careful outlines, but in the end this has created a new aesthetic, one of protest, full of popular longings, and that lives in the full multitude of rebellion, is strong and great and captures us with the emotion of battle — this is life.”

Throughout his career, Méndez remained mistrustful of the government, which changed ideologically from administration to administration throughout the decades. He worked with and for them at times, and accepted support from them at times, but he ultimately remained independent, focused on the people, and intent on reaching as many as possible with his art and words.

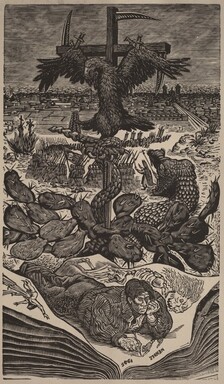

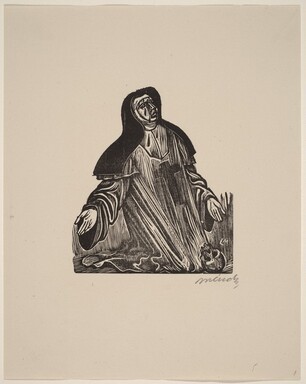

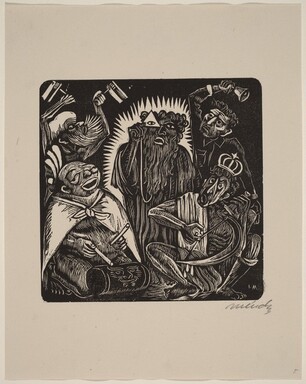

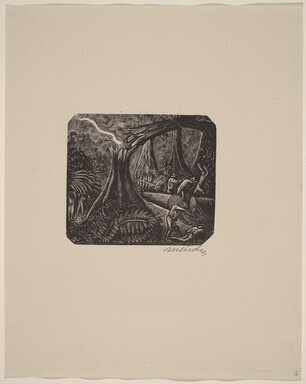

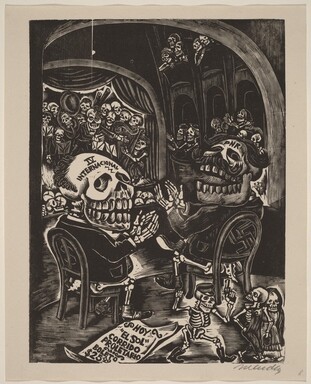

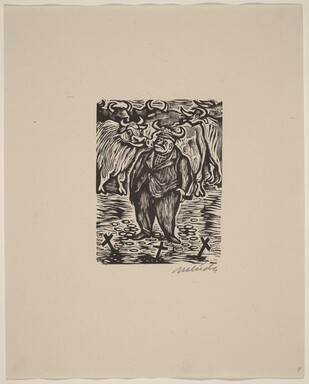

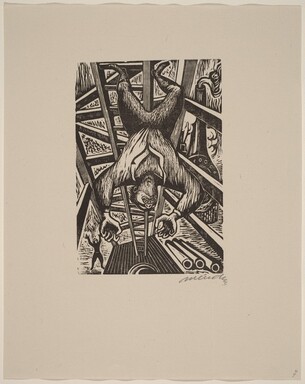

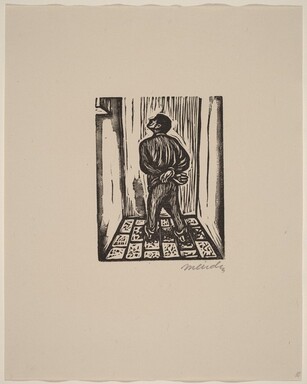

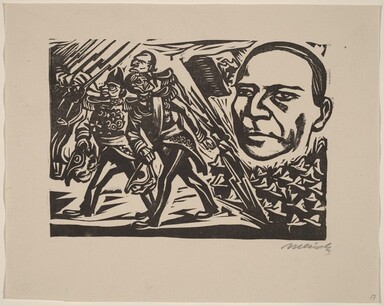

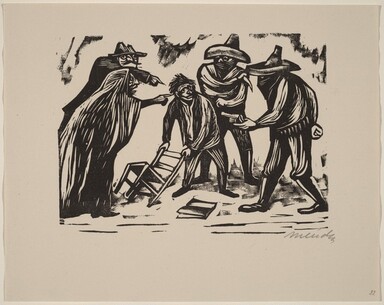

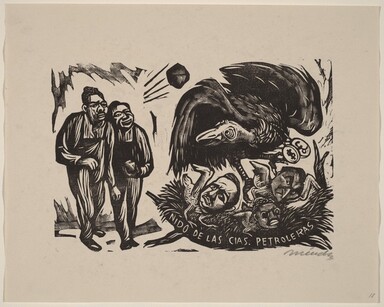

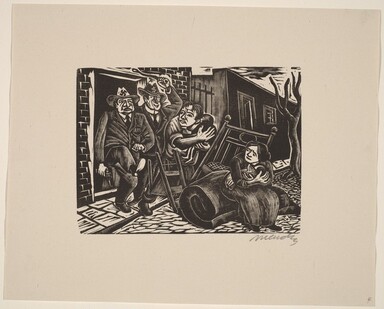

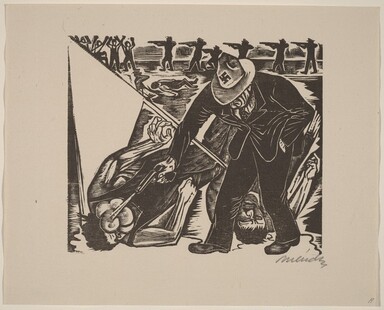

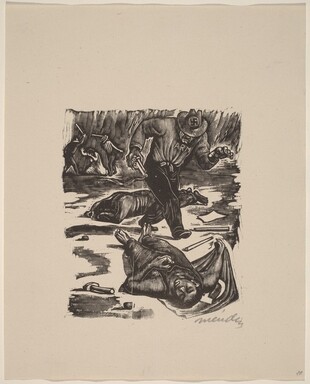

Méndez painted ordinary people working — factory workers and farm laborers — and he painted scenes of protest and oppression. He was deeply influenced by the prints of José Guadalupe Posada, one of the most famous of Mexican artists, who worked as an illustrator for newspapers and magazines, providing biting commentary on everyday events, politics, and the stories that affected the people. He was a sharp satirist who adopted the medieval dance of the dead images to create calavera prints, featuring skeletons engaged in recognizable human activities with all the familiar human foibles. Méndez further adapted these images to create powerful revolutionary criticisms of the corruption in the world.

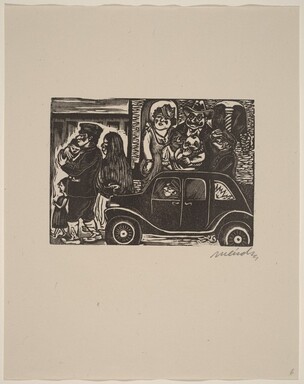

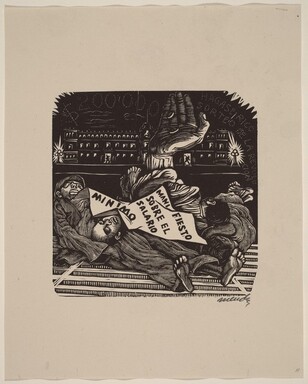

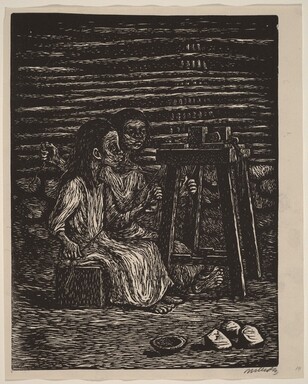

Little is known about Méndez’s private life, and he did not attain much recognition as an artist, because for him art wasn’t about the individual artist, it was created communally to be shared universally. He often worked and lived with groups of artists, writers, and revolutionaries, who supported each other financially as well as artistically. He believed in the collective production of art in whatever form necessary to reach as many people as possible. He became closely associated with, though never a member, of the wide-ranging group of artists called Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios and the Taller de Grafica Popular, as well as other smaller organizations that came and went over the years. He contributed to a variety of newspapers that were printed on cheap paper and distributed as widely as possible, including Llamada (Cry), Frente a Frente (Face to Face), and others, as well as distributing prints and hanging posters. He was a founding member of the Taller-Escuela de Artes Plasticas, established in 1935, which served as a shared resource for artists to create prints and other work, as well as a night art school for workers. Education and art education continued to be crucial to bringing about a better world for everyone. His graphic illustrations were often accompanied by text, and when people were moved by the illustrations to understand more, teachers would be able to explain the words to them, and they would understand the power of reading.

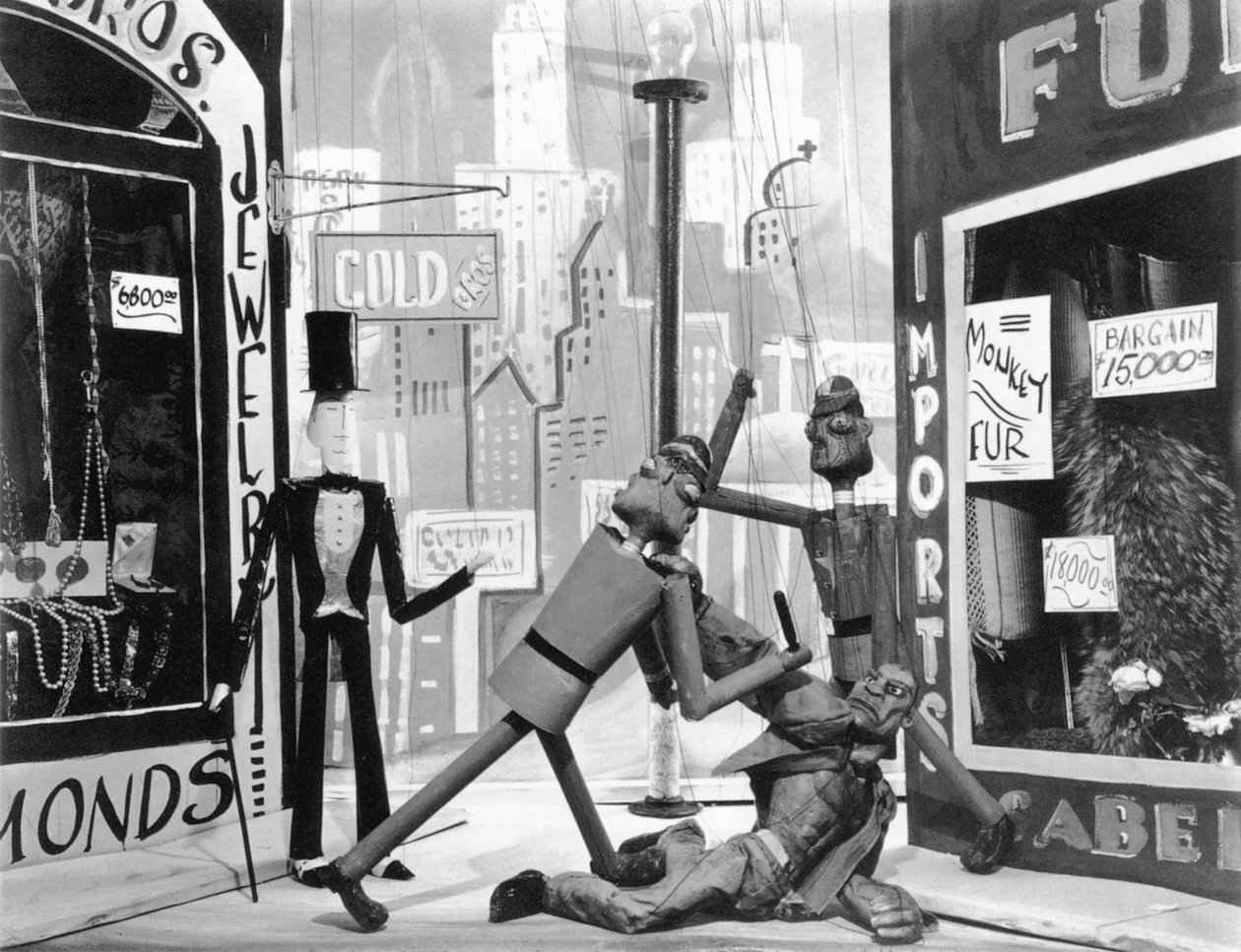

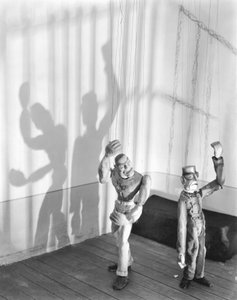

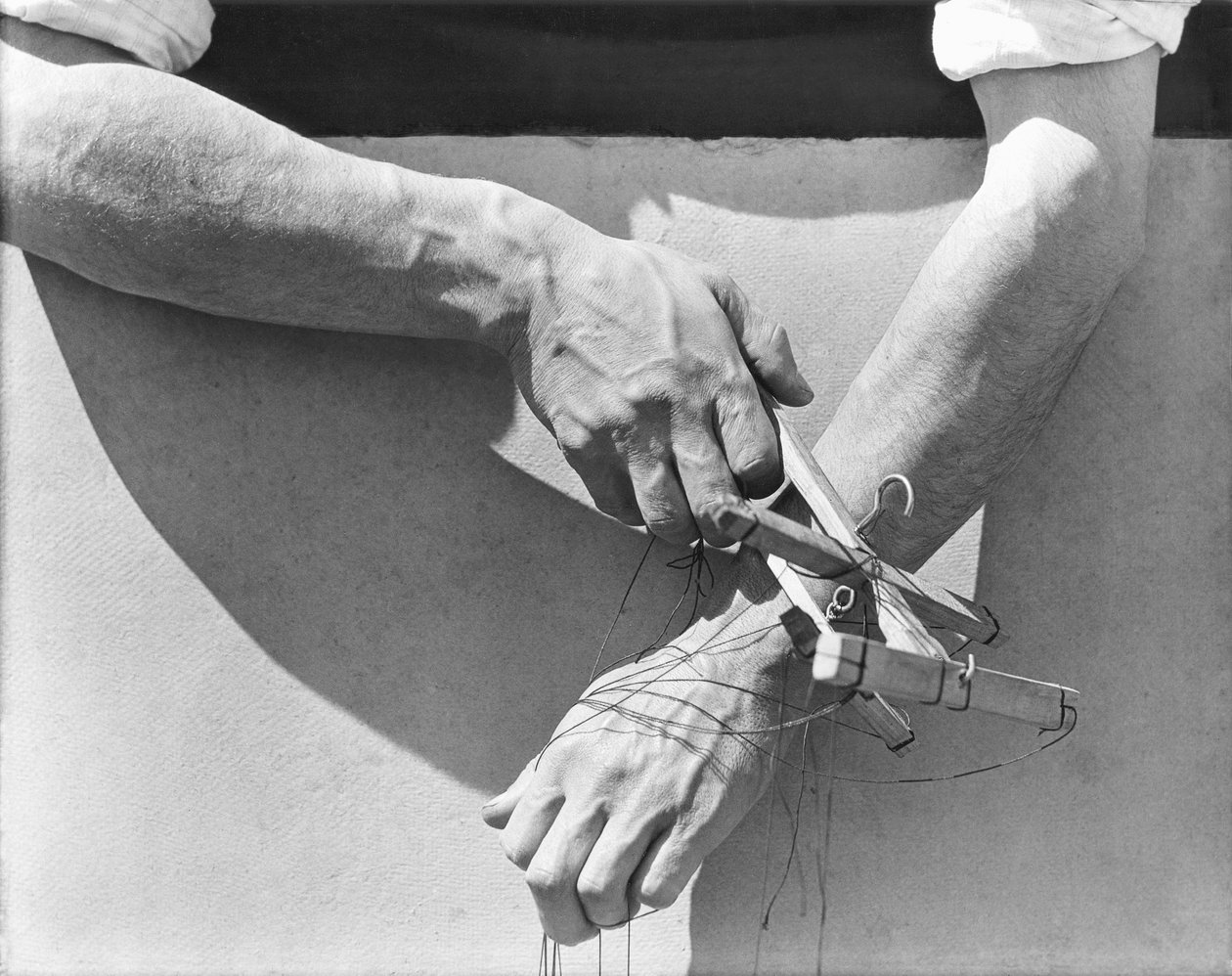

Tina Modotti’s photographs of puppet theater in Mexico in the 30s.

He also worked with puppetry, building on a Mexican tradition in conjunction with like-minded artists to bring his message to children in a way that they could be directly involved with. He opposed the open-air schools, which he saw as promoting European methods and producing art for art’s sake, and he thought that puppetry, as an involved, hands-on production would involve children in a way that would make their education more valuable and meaningful. Along with other artists of the day, he was involved in an artists’ community devoted to making puppets, writing plays, and bringing performances to communities everywhere. They used folk tales to share ideas of revolution. Méndez wanted to make a “puppet theater with puppets or marionettes, that the students would manage; for them to do everything, puppets, decorations, etc.., because the theater has always had a plastic sense and in it children can translate their impression, their emotion.”

Artists would travel from town, identify the municipal building and paint it white and label it as such, then they would make a puppet theater, then they would identify the problems facing the citizens of the town and do whatever they could to solve the problem. And they would combine all their new knowledge of each town to enlist students to perform plays and paint murals addressing the issues facing the community.

Méndez and his comrades also shared corridos, which were popular songs that functioned almost as news stories. They would relate tales of oppression, tales of everyday life, tales of political or historical events, but always from the point of view of the ordinary person. Méndez printed the words to popular songs on posters, with illustrations surrounding them. Méndez’s work was always independent from mainstream sources of news and art, and he used the forms of communication that seemed like the means for under-valued people to talk directly with one another, to join together and become stronger and better educated.

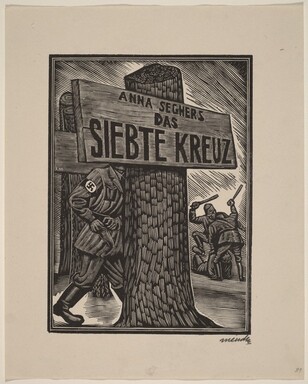

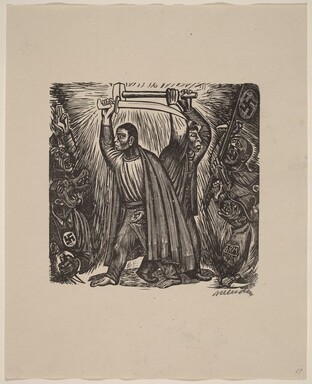

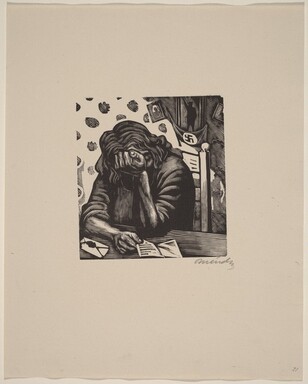

The rise of fascism, in Mexico as well as in Europe, in the decades before the Second World War, was of great concern to artists throughout the world, and Méndez was no exception. He and the artists he worked with in Mexico wrote anti-fascist screeds, made anti-fascist art, and joined forces with artists and writers in America and Europe to combat the scourge.

And here we are again, with the nightmare of fascism spreading throughout the U.S. and abroad and a terrifying feeling of powerlessness against it. We need education to fight the tragic ignorance that brought us to this sorry place. But as the next administration and the evil (mostly) men who will be in power have shown, with no shame, they do not value education. Worse, they know that an educated public is a dangerous public and one that would understand that everything they are trying to do will make working people poorer and less safe. They cannot survive if the people have that knowledge, so they will keep it from them.

In the digital age, it should be easier and cheaper to make and share art and words. Sadly, it seems easier to share misinformation than information, and the powers that be are pouring evil-villain amounts of money into ensuring that they retain control of it. There must be some way to communicate with people in the ways that ordinary people communicate. There must be some way to spread truth, art, hope, and rebellion and crush the lies and hatred. We have some thinking to do. And then we must act.

1 reply »