As disarmingly beautiful as the photography of Faraz Ravi is, its true power lies in its ability to remind us that there is meaning beneath the surface of the image. In the strength of the trees and the ghosts all around them, we find so much weight and wisdom and reverence, but there’s lightness and hope as well — a real feeling of capturing a moment in the endless cycle of growth and decay, which we’re part of but will never fully understand. We were grateful to have a chance to ask Faraz some questions about his work.

Magpies: “One of the deepest and strangest of all human moods is the mood which will suddenly strike us perhaps in a garden at night, or deep in sloping meadows, the feeling that every flower and leaf has just uttered something stupendously direct and important, and that we have by a prodigy of imbecility not heard or understood it. There is a certain poetic value, and that a genuine one, in this sense of having missed the full meaning of things. There is beauty, not only in wisdom, but in this dazed and dramatic ignorance.”

I love this quote from Robert Browning – I love the idea that everything is connected and there are patterns and cycles of life that we will never understand. I believe we’re part of it, of course, as humans, but mostly as spanners in the works. Many of your photographs seem to somehow capture something of this indefinable, mysterious, weighty, weightless connection. How do you feel about our place in the world, and how do you think about your photography as a tool for expressing that?

It’s a beautiful quote. In a sense we are misaligned to the deep resonance of our universe, aloof to its whisperings and in denial about our own mortality. We have conflated the physical insignificance of our existence with a deafening meaninglessness that has led us to become increasingly destructive and less willing to listen. I see our unique place as the interpreters of symbols, seekers of meaning as evidenced by our mental and spiritual capacity that otherwise contribute little to our mere survival. Without this, photography, poetry or any art is simply an accidental composition of random artefacts of no value, there is no beauty. My perspective is resolutely theistic, a great unity that connects us all, the signs in everything interior and exterior if we are not deafened to them. In my photography I simply try to convey a sense of existence beyond the material, and time stretched out vastly beyond the moment. What was witnessed in the image extends beyond it material presentation in many dimensions. If I can’t do this in the image, I’m content to simply allude to the mystery beyond the surface.

Similarly, surely one of the most important cycles is that of growth and decay, and somehow there’s hope even that decay – death nurtures rebirth. Do these ideas inform your work?

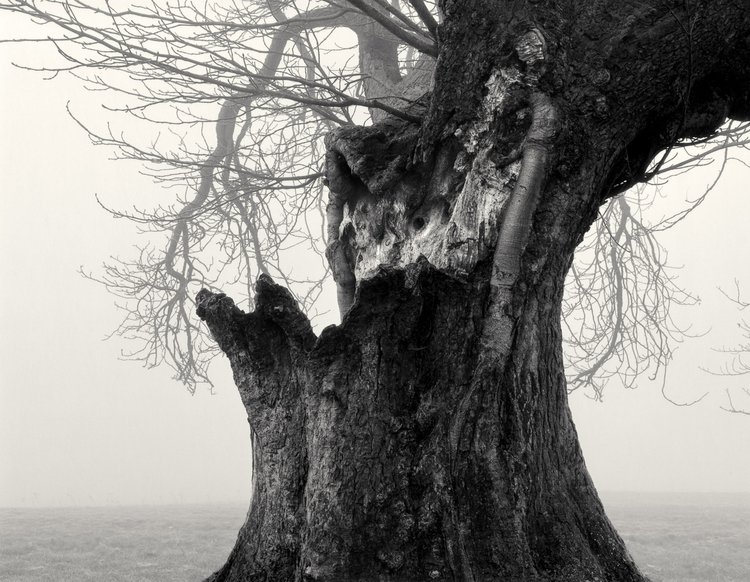

Very much so. The life, death and the composition of beings through time from essentially the same material suggests an existence beyond the material form. A parallel theme considers the interior and exterior of the human experience as expressed in the interior and exterior of the landscape. I photographed a number of trees over a few years, seeing first their exteriors and beautiful forms, followed by the violence of their destruction and their exposed interiors or gaping wounds. Some survived, others did not, it depended on what was hidden and the patience of their growth. In a world in which superficial appearances are valued beyond almost anything else, I found this subtle metaphor meaningful.

In a noisy world in which we’re constantly bombarded by images – we can take hundreds of disposable images a minute – it seems as though you find some silence and grace, which gives value to the moment that you capture as well as the photograph that captures it. Can you talk about your process of capturing and developing photos and in particular the choices that you make?

It seems cliched to talk of slowing down, yet this is what has been creatively fruitful in my process. A single decision has dictated the maximum pace I can work at and I have accepted the constraints that come with it. That decision is to work with film and in the darkroom. In my mind I have locations to return to, I wait for the light, it’s usually early morning and typically cold. Often I have an idea of what I want to capture, I know most of my locations well. Of course working with film there’s no preview on the back of the camera and I don’t bracket a lot, often I just take a single carefully considered shot. Sometimes I succeed, other times I fail. I accept the failures, it’s part of the process. Then in the darkroom I see where I want to take the capture in print, choosing the balance of impact and absorption. Impact often comes through contrast, and absorption with detail and levels of depth. With the constraints in darkroom processing the final print is always a representation of the captured image in some way. It may be highly interpretative, but it is never fiction. There is a path between the exposed particles in the paper and the light of the moment…I always want to maintain this.

We’ve talked about our place as humans in nature, but on another level, your work seems to question our connection to each other, our way of examining the world and sharing what we find. What is the role of art in finding some sense in the nonsense, some substance in the superficial?

The act of seeing is interpreting reflected light that enters our eyes. But neurologically we know that sight is not simply image composition based on optics, but is highly interpretative and draws on our experience, knowledge and ability to delineate the world. To my mind the purpose of image making, or making anything thoughtful is bringing something not ordinarily seen closer to the surface perceived by the artist, offered to others to see in their own way if they wish. It is a sometimes a journey of absorption at others a fleeting spark of thought. Both allude to there being more to the world than the photons that meet the eye. For me art should engender humility and reverence and inspire wonder rather than hubris.

Your photographs of trees remind me of those of one of my heroes, Eugene Atget, and I see something in your process (as I understand it) that echoes his great effort – of carrying heavy equipment, spending time with each print. Berenice Abbott believed that Atget felt a sympathy and empathy with the trees. To what extent do you think of trees as kindred spirits? To what extent are you approaching their images as a portrait photographer?

I once approached a tree to photograph only to find a woman around the other side of it, she was silently hugging the tree. She was not a hippy or new-ager, just a very normal looking woman. Exchanging a few words it was clear she felt something of the soul of the tree in a very real way and would often return to the same tree. She spoke of the feeling as the most obvious thing. Though brief, it was quite a moving experience. I find Josef Sudek’s pictures of trees and forests hard to interpret without believing he felt a real connection to his subject. Nothing less than a deep affinity could produce such sympathetic beauty, often of trees wrecked by storms. Needless to say, he is one of the master photographers I have been influenced by.

I’m fascinated by the idea that the pandemic made us look at our world – our immediate world – with new eyes. We had the chance to notice things we might not have ordinarily taken the time to notice, and to observe the way the things that are familiar change with the days and the seasons. You beautifully capture that in your photo books. But you’ve travelled as well. How is the act of looking (and capturing what you see) different for you whether you’re tethered or away from home?

I like to photograph what I’m familiar with and can return to, the pandemic simply compounded this habit for me. I feel that knowing the subject helps me to capture it, as does failing to capture it a number of times previously. I love the work of John Blakemore and the fact he produced what he did in the most ordinary of landscapes. I don’t think this is universal, others produce beautiful work in new locations and seem to thrive on that challenge. However focusing on what is close to you, however unremarkable, forces you to bring more of yourself into your work. Still, travelling to new places and photographing in a deliberate way is a real privilege and a special way to see a new place, I do enjoy doing it when I can. I sometimes even take large format gear and spend a whole day just taking 10 or so photos, a real antithesis to blasting away hundreds of photos on a phone, looking at everything whilst seeing almost nothing. I’ve been occasionally guilty of that too and always regretted it!

There’s a painterly quality in your work – in the way that you capture the texture of bark, moss, ice, branches, and in the care that you give to the choice of paper and the variations of warmth and coolness in your work. Can you describe the balance between capturing an image and creating an image, in terms of form, composition, execution.

There is space between image capture and creation, specially with film and the darkroom process. That time offers the opportunity to consider how to realise the image. I try to compose in the viewfinder and only occasionally crop in to change the composition. When we see our environment we have the advantage of two eyes and a moving viewpoint, as such we are very effective at disambiguating the scene and isolating what interests us. We can do the same with sound. But when flattened to an image plane much of that delineation is lost, and working in black and white this is even more so. This is why I like hazy or foggy conditions, it helps to isolate the subject. In the darkroom I’ll sometimes mask background regions to print them with less contrast to bring out the main subject, or give the subject more light to direct the eye. I also sometimes part sepia tone and the point at which the split occurs between grey and sepia can also be used to help identify the background. There are a lot of techniques involved that I have learned from others and through experience over the years, but what matters in the end is the emotive response to an image. I usually evaluate this as the balance between impact and absorption and the absence of distraction. The sense of an image slightly offset towards unreality and almost unphotographic is what I often aim for and is perhaps what is thought to be ‘painterly’. Initially it was not deliberate, but I found I was printing like this and followed it.

Part of that painterly quality is the gorgeous contrast between light and dark, which comes across as a reverence for the light and shadows that create the photograph itself. How do you think about light and dark, lightness and heaviness in your work?

Working in black and white it is essential to be very cognisant of light, how it falls and fades and its absence. Nothing gets me out of the house, camera in hand, more than beautiful light and atmospheric conditions. Often I am in a state of awe when photographing, the photography almost taking a back seat to the wonder of being in the surroundings. It is always the light, not the subject that makes me feel this way.

Working in the landscape my subject is usually darker than the background, yet the eye is attracted to the light and wants to wander off into the background. For this reason, the subject must hold the eye sufficiently before it is lost or starts hunting around confused. I think of shadows as creating mindful intrigue, whilst light creates visual interest. It is essential to balance the two and the merging of one into the other to form the desired emotive response. Most of my backgrounds are not too bright for this reason, unless that brightness is contributing to the depth as part of the spatial structure of the image.

The eye’s movement can convey a sense of depth across what is a flat image plane. You may even feel the sensation of mind refocusing in response to a perceived change of distance. Using this it is possible to enhance the spatial quality of an image, to provide compression or expansion. I often burn (darken) the lower part of an image to provide a sense of depth, or brighten a point of departure or interest. At other times shadows are used to contain the image. But I seldom invent the fall of light completely (though possible in the darkroom). Rather I enhance or subdue what was already there, in reality or in some latent sense. That’s what feels right to me, a sort of reverence I suppose.

“I am an artist living in the UK, interested in the changing landscape around me as metaphor for the human condition and societal change. My primary method is analogue, working with large format, medium format and 35mm cameras on black and white film. My work is mostly produced in a darkroom using traditional silver gelatin process and toning methods. See more at farazravi.com and on instagram at faraz_ravi.“

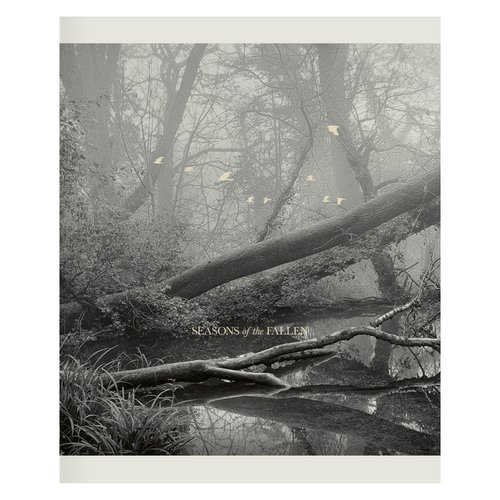

“Seasons of the Fallen explores the fluctuations of a familiar landscape as storms roll in and take their victims. The images as inspired by the intuition that trees are self aware or at least beings in some way, an intuition given weight by recent discoveries on the internal life of trees. This is contrasted with the continuous material forms through which they move and ultimately into organic material from which new life begins.” Seasons of the Fallen, a photobook of 73 images is available to order here.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, photography