By Arthur Davis

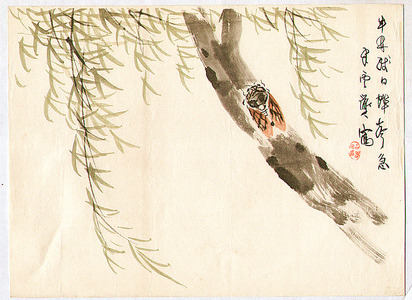

Oku no Hosomichi – 奥の細道

in the stillness—

sinking into the rocks,

is the cicadas’ cry

Let us abandon the self. Let us enter the mind of Matsuo Basho for a moment.

From a distance we see him standing outside his small house in Fukagawa, underneath the famous banana tree given him by one of his students. The tree has grown over the years and now towers over our small group. It bears fruit. Let us now imagine that it is a summer’s day and the sky is blue except for the occasional cloud that shades the sun. Basho and his disciples are discussing the art of the haiku. From our lofty perch let us descend and enter the mind of Basho.

Matsuo Basho: “Things, like humans, have qi, (氣). It is a life spirit, which can be felt. This is the universal force that makes up and binds all things together. It is paradoxically, both everything and nothing.”

Toho [Basho’s disciple]: “How do we learn of this spirit? How do we feel it?”

Matsuo Basho: “The mind merges with the object, which is taken in nature without obstruction. Detach from oneself, enter the object with the mind, feel the subtlety of the thing. Let the mind become the object.

Learn the pine from the pine, the bamboo from the bamboo.”

Toho would later recall this conversation in his red booklet, Akazoshi:

The master said: ‘Learn about a pine tree from a pine tree, and about a bamboo plant from a bamboo plant.’ What he meant was that the poet should detach the mind from his own self. Nevertheless, some people interpret the word ‘learn’ in their own ways and never really ‘learn’. ‘Learn’ means to enter into the object, perceive its delicate life, feel its feeling, whereupon a poem forms itself. Even a poem that lucidly describes an object could not attain a true poetic sentiment unless it contains the feelings that spontaneously emerged out of the object. In such a poem the object and the poet’s self remain forever separate, for it was composed by the poet’s personal self.

Risshakuji, 立石寺

After visiting Seifu in Obanazawa, Basho detoured south to Yamadera, 山寺, the popular name for the Buddhist temple Risshakuji, 立石寺. It is located on the steep slopes of Mt. Hoju, in northern Yamagata Prefecture.

It was there, that Basho composed his well-known haiku on the cicada.

Basho’s Notes

From Oku no Hosomichi: Risshakuji Temple

“In Yamagata province is Ryushakuji Temple. Founded by the great teacher JikakuDaishi, this temple is known for the quiet tranquility of its grounds. Told by everyone to see it, I left Obanazawa. Reaching it in the late afternoon, the sun still lingering. I arranged to stay at the foot of the mountain with the temple priests. I then climbed to the temple itself near the summit.

The mountain consists of boulder upon boulder covered with ancient pines and oaks. The stony ground in the color of eternity, covered in velvety moss. The shrine’s doors were barred and no sound could be heard.

I crawled on all fours from rock to rock, bowing at each shrine, feeling the purifying power of this holy place filling my being.”

In Chinese and Japanese lore, cicadas are high-status creatures one seeks to emulate. They are considered pure because they subsist on dew and sap. Lofty because they perch in trees. In summer, their call is loud and long.

By crawling around, Basho showed respect and emulated the cicada. Perhaps, he hoped, his words could penetrate even the stone itself.

As they have.

立石寺

山形領に立石寺と云山寺あり。 慈覚大師の開基にて、殊清閑の地也。一見すべきよし、人々のすゝむるに依て、尾花沢よりとつて返し、其間七里ばかり也。日いまだ暮ず。梺の坊に宿かり置て、山上の堂にのぼる。岩に巖を重て山とし、松柏年旧土石老て苔滑に、岩上の院々扉を閉て物の音きこえず。岸をめぐり、岩を這て仏閣を拝し、佳景寂寞として心すみ行のみおぼゆ。

Summer, 1690

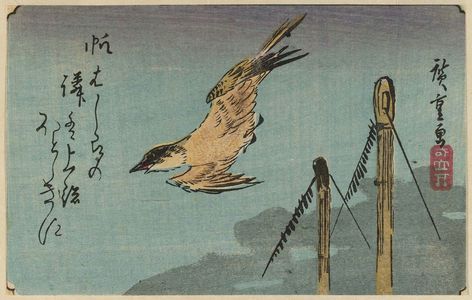

Even in Kyoto

Longing for Kyoto

– the Cuckoo

京にても 京なつかしや 時鳥

Kyoo nite mo, Kyoo natsukashi ya, hototogisu

By Japanese reckoning, it was the era called Genroku (元禄, meaning “original happiness” or perhaps “the beginning of happiness”). It was the third year of the reign of Emperor Higashiyama, 113th emperor of Japan.

That spring Matsuo Basho had completed his trip that would become in time his most famous travelogue, Oku no Hosomichi, Journey to the Far North. Not wanting to hurry back to Edo, where Basho had lived and written for the last 46 years, he decided to stay in Kyoto for four months in a modest hut called Genjuu-An 幻住庵, located on the grounds of the Chikatsuo Shrine.

Summer was approaching. In Kyoto’s trees, now full of green leaves, one could hear the plaintive cry of the cuckoo, “Kyoo-Kyoo.” Basho recalled his early days a student in Kyoto.

Matsuo Basho was 56 years old. Basho’s own death came in 1694.

Notes on translation

京 Kyoo, Kyoto, appearing at the beginning and repeated to imitate the sound of the cuckoo bird. Some say the birds call, “kyoo-kyoo,” is the cry of the dead longing to come back.

なつかし natsukashi, a feeling of nostalgia, a joy for the remembrance of the past. I have used longing.

時鳥 hototogisu, The cuckoo bird. Basho leaves us with the image of a cuckoo bird and nothing more. Nothing else was needed since the cuckoo was a frequent subject of poets.

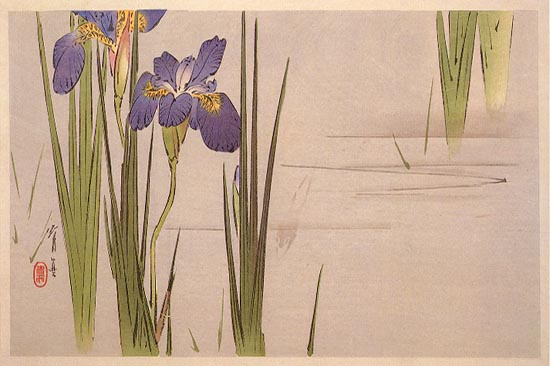

kakitsubata

An iris

brings to mind

a hokku

kakitsubata ware ni hokku no omoi ari

杜若われに発句のおもひあり

It is the fall and the iris blossoms though long gone, still bring to mind the memory of my grandmother, for it too was her favorite flower. For Matsuo Basho, flowers were an inspiration and he wrote of the kakitsubata, the blue water iris, at least three times. This one in 1685, following the death of his mother in 1683.

Basho’s haiku is based on the eighth-century hokku and Noh play of Ariwara no Narihira.

In the play, a traveling monk seeing iris blossoms on the bank of a stream approaches to admire their beauty. It is strange to him how the flowers are incapable of knowing their own beauty. A young woman watching him studying the flowers approaches him. This place is called Yatsuhashi, she says, and it is famous for its irises. When he asks if they have been the subject of a poem, she tells him of the poet Ariwara no Narihira of the Heien Period who composed the poem, “Just as a karakoromo robe comfortably fits my body after wearing it a long time, I comfortably fit my wife. Alas, I came east, leaving her behind in Kyoto. It is heartbreaking to be so far apart.”

By 1685, Basho has become a tabi no kokoro 旅の心 literally “traveling heart.” His mother died in 1683 and the following year he left Edo on one of his first wanderings. In 1685, the year of this haiku, he presumably visited the famous Yatsuhashi Kakitsubata Gardens, which reminded him of the poet Ariwara no Narihira, who wrote a hokku (an introductory poem) and a Noh play based on the flower. The play is set in early summer, near Yatsuhashi (Eight bridges) in Mikawa Province, present Aichi Prefecture.

Kakitsubata, the hokku

Kakitsubata is a hidden word (the first two characters in the five lines) in the acrostic hokku (poem) by Ariwara no Narihira from Tales of Ise.

から衣

きつゝなれにし

つましあれ

ばはるばるきぬる

たびをしぞ思

Ka-ragoromo

kit-sutsu narenishi

tsu-ma shi areba

ha (ba)-rubaru kinuru

ta-bi o shi zo omou

Notes on translation

Kakitsubata (Chinese, 杜若, Japanese, かきつばた) – one of three Japanese species of iris, is found along waterways and is usually purple or blue in color. In English it is sometimes translated as “rabbit-eared iris”. The kakitsubata is cultivate in the Yatsuhashi Kakitsubata Garden (八橋かきつばた園) at the Muryojuji Temple. It is also the place where Japanese poet Ariwara no Narihira was inspired to write his verse.

Hokku, 発句 – the opening stanza of a series of collaborative linked poems, renga.

Summer, 1689.

The Mogami River tumbles into a mountain valley in northern Yamagata Prefecture. There one finds peaceful Obanazawa, 尾花沢, meaning Marsh of Irises. Matsuo Basho, and his companion Sora, are staying with Seifu, a well-to-do safflower merchant and haiku poet.

making coolness

my lodging

for a while, I may rest

涼しさを我宿にしてねまる也

suzushisa o waga yado ni shite nemaru nari

Crawl and creep

From under this shed

You loud mouth frog

這出よかひやが下のひきの声

Haideyo kaiya ga shita no hiki no koe

Note. Hai, the first character in this haiku has several meanings. Creep and crawl is the intended meaning, but as homophone, it means to bow reverentially. Another meaning is “to give up.” Kaiya, the shed where the silkworms are kept. Kiki. A Bullfrog. Frogs and toads eat caterpillars. Kaiya, also a Japanese feminine name meaning “Forgiveness.”

recalling to mind

an eyebrow brush

benihana (Safflower blossoms)

まゆはきを俤にして紅粉の花

mayuhaki o omokage ni shite beni no hana

Oku no Hosomichi, Obanazawa, Summer 1684, Matsuo Basho

Note. Mayu, まゆ the first two characters, means eyebrow. Its homophone, 繭 a silkworm cocoon. Beni no hana, 紅粉の花, literally red powder flower. Safflowers produce yellow and red dyes which range from light yellow through pink, rose and crimson. For this reason, they are popular in cosmetics.

Basho’s annotation from the travelogue, Oku no Hosomichi:

“I visited Seifu in Obanazawa. He is a rich merchant of a truly poetic turn of mind. He has a deep understanding of the hardships of being on the road, for he himself had often traveled to the capital city. He invited me to stay at his place as long as I wished, trying to make me comfortable in every way he could.”

尾花沢にて清風と云者を尋ぬ。かれは富るものなれども、志いやしからず。都にも折々かよひてさすがに旅の情をも知たれば、日比とゞめて、長途のいたはり、さま%\にもてなし侍る。

Basho added this haiku by Sora:

those tending silkworms keep their ancient appearances

Sora

蠶飼する人は古代のすがた哉

kogai suru hito wa kodai no sugata kana

Note. Kogai, 蠶飼. Silkworms are the larval form of the silk moth. The caterpillar spins a cocoon out of silk fibers for its metamorphosis into a moth. Silkworms have been domesticated since at least 3500 BC.

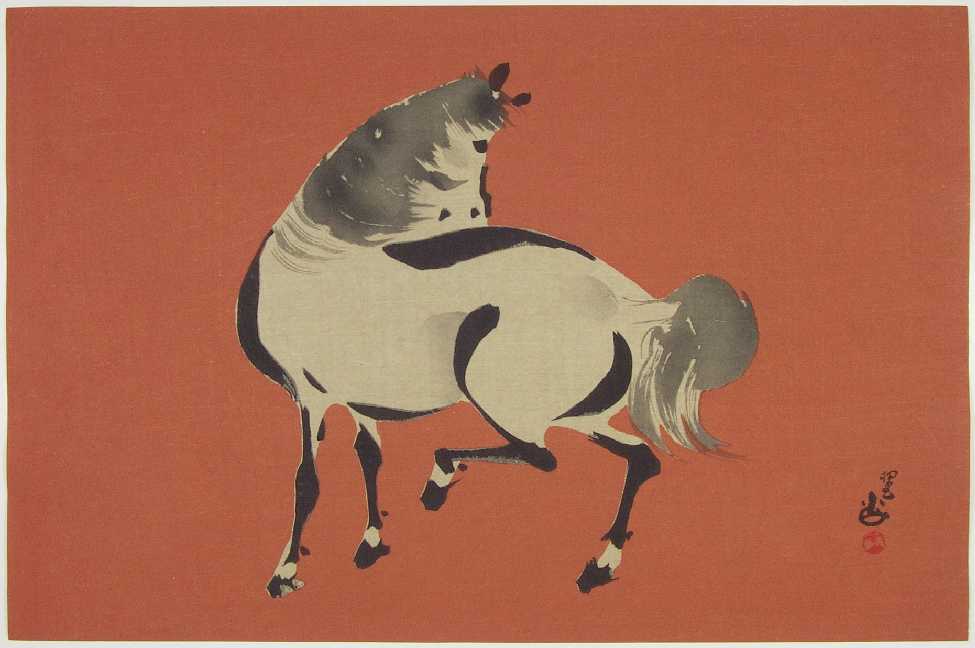

Tenwa, 3rd year, Summer

1685, Age 41

In late 1684, Matsuo Basho left Edo to once again travel alone on the highways connecting the capital and Kyoto. Along the way he rethought his haiku style and reflected on life. In 1685, as summer ended, he made his way home back to Edo.

A horse, peaceful and quiet

(boku, boku, clip clop)

Oh, I see myself

In a summer field!

馬ぼくぼく/ 我を絵に見る/ 夏野かな

Uma boku boku ga o e ni miru natsuno kana Matsuo Basho, Summer, 1685

French

Un cheval, calme et tranquille (clic clac)

Oh, je me vois

Une image sur le champ d’été !

Meanwhile in Europe

René Descartes (1596–1650), French mathematician and philosopher, is inquiring into the difference between perception and reality. “Cogito ergo sum,” he concluded, all that I can know is that I think, therefore I am. Basho is one step removed. “Learn about pine trees from the pine, and about bamboo from the bamboo.”

Is Basho now thinking he is the horse, or the rider, peacefully walking through a summer field?

Once in Montmartre

Present day, more or less, remembering.

Either way, Basho is “going to the balcony,” (the painting), a mental attitude of detachment where one can calmly see what is happening.

Years ago, it seems like yesterday, I was with an artist friend in Montmartre, Paris’ artist village that sits on top of a hill. Five French artists were lined up with their subjects in front of a cafe where my friend and drank beer and watched. One artist, the best, would occasionally look away and shake his head before turning back to the canvas. When I asked my friend why he did this, he explained that the artist was removing his preconceived notions from his head, detaching himself from the scene and painting what was there and not what he perceived.

Notes on Translation

Uma (horse) boku boku (boku meaning “I” or “me” in a humble way, boku boku, onomatopoeic, the sound of walking), ga (“I”, “myself”) o (“o” separating Basho from the action of riding the horse) e (picture) ni (at) miru (look, looking, watching) natsu(summer) no (field) kana (particle indicating both doubt and exclamation, “oh my”)

Sugiyama Sanpū (1647-1732) was a wealthy fish merchant in Edo and life-long patron of Matsuo Basho. He provide Basho with the Bashoan (banana) cottage in Fukagawa, Edo. Sanpu was present when Basho and Sora set off on the trip that was to become Oku no Hosomichi (1689). Basho referenced Sanpu, saying “the eyes of a fish (meaning Sanpu) are full of tears.”

Matsuo Wanting to Change

Enpo 9, Summer 1681

Basho is 38 years old,

Likely at Lake Biwa

Keep in mind, at the age of 38, the poet then called Tosei (unripe peach) was wanting to change.

Nature has made you the way you are, but Nature can change how you appear. Consider Zhuangzi’s saying, “A duck’s legs are short, to stretch them would worry him. A crane’s legs are long, to shorten them would make him sad.” (Zhuangzi, 6:8-9).

Summer rain

on the cranes, the legs are

becoming shorter

五月雨に鶴の足短くなれり

samidare ni tsuru no ashi mijikaku nareri

Change was afoot. In the summer of 1681, outside of Edo, by the Sumida River, Basho was getting used to his new home in the then rural Fukagawa District. In relative isolation he began the study of of the ancients including Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi. The cycles of the seasons, the appearance of the egrets and cranes nesting and fishing along the river, and especially the rainy days of early summer were subjects for thought. Zhuangzi says keep your inborn nature, Buddhism teaches change. So Basho says, the quickest way to change the world around you is to change yourself, i.e., move to Fukagawa, live in a cottage, and, walk in the river to shorten your legs.

samidare (literally 5th month, but Basho intends “early summer rain”) ni (on, referring to the crane legs) tsuru no ashi (crane legs) mijikaku (short) nareri(becoming)

Summer of 1691

May 5, 1691, age 47,

Maybe, Otsu, Japan

Recalling his mother, on Children’s Day?

Seeing a woman wrap sticky rice dumplings in a bamboo leaf and tie it with a string, tucking her hair behind her ear. Did Basho recall his mother?

Holding a dumpling

in one hand, she tucks

her hair behind her ear

粽ゆう 片手にはさむ 額髪

Chimaki yuu katate ni hasamu hitaigami

By the summer of 1691, Basho had left the Hut of the Phantom Dwelling, on the shores of Lake Biwa, but he was not yet back in Edo. One imagines he was saying farewells to friends in Otsu or nearby Kyoto before going home to Edo. Home, that is what Edo had become. And the little cottage in Fukagawa, a familiar place to return to.

Three years later, Basho would be dead. He chose to be buried at the Buddhist temple of Gichū-ji (義仲寺) in Otsu.

Notes on Translation

The Japanese traditionally serve and eat Chimaki during the Tango no Sekku(端午の節句, Children’s Day) on the fifth day of May. Another reason to suppose Basho was thinking of his own mother and childhood.

Chimaki (a sticky rice dumpling wrapped in a leaf) yuu (expresses volition, the desire to do something) katate (one hand) ni (particle for indirect objects) hasamu (insert, place) hitaigami (bangs, forehead hair)

Read more of Arthur Davis’ thoughts on Matsuo Basho’s poetry here.

Categories: featured, literature, poetry