By Alice Courtright

In her first solo museum show, artist Stella Maria Baer weaves earth and mineral pigments with oil to create paintings that transfigure loss, motherhood, and memory.

Moon Horse and Sky

Taos Art Museum

June 4-July 21, 2024

I trust my work. It’s a collaboration with the material,

and when it’s viewed, it’s a collaboration with the world.

— Kiki Smith

The painter and photographer Stella Maria Baer is from New Mexico, and makes pigments from the canyons and deserts and fields around her, suspended in walnut oil alongside earth and mineral pigments from all over the world. Pigments from a rock collected under her horse’s hooves are woven together with ochre earth pigments from France, the same ochres used by Van Gogh in his paintings of sunlit fields. Baer breaks down the rocks until they are dust and then mixes them with oil. “I love the alchemy of gathering the dirt beneath our feet and transfiguring it into paint. We are on sacred ground,” Baer told me in one of our conversations.

Baer comes from a family of artists. Her grandfather, Morley Baer, was a landscape and architectural photographer in California, who worked with Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. He would take Baer and her brother on photography trips out in Point Lobos when they were children. “He worked with a medium format camera that he would haul out onto the side of a cliff and then wait, watching the sky,” Baer says. “Watching him take those photographs as a child still haunts me, especially when I’m carrying my easel out into the desert to paint or waiting in the field with my camera, watching the horses move through the wild grasses under the pink sky.” Her grandfather would wait until things aligned, until he saw something appear in the sky.

Baer’s mother was a weaver. One grandmother was a painter, the other a sculptor. Baer remembers, “Growing up, my mother would say, ‘Let’s not go anywhere, or buy anything. Let’s make something with our hands.’” Baer grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and, in the summer, she worked as a wrangler, washing dishes and working with the horses at her mother’s family’s ranch in Wyoming, which bordered Medicine Bow National Forest. She attended college and graduate school in New England, and then spent many years on the East Coast. After college, painting became a form of prayer for her, a way of wrestling with a growing desire to return to New Mexico.

No art is made in a vacuum–every artist has teachers with whom they remain in conversation. One of Baer’s teachers is the painter and sculptor Titus Kaphar, whose large-scale works reckon with American history, race, memory, and the role of the past in the present. Baer worked as his studio assistant in New Haven, while in graduate school at Yale. “Titus believed his paintings were sacred. Watching him bring his work into being helped me believe in my own visions. Sometimes we need to see someone do what feels impossible before we can believe it is possible,” Baer told me. He showed her some of his first drawings, and Baer couldn’t believe the difference between his paintings in exhibitions and his early attempts. Titus cast a vision for what it meant to be a working artist. Baer says,

When I finally started showing my paintings to other people I was surprised to hear that the paintings spoke to people in ways I couldn’t have expected or predicted, that I didn’t control or understand. The paintings feel like they are both a part of me and coming from a place beyond me. I feel similarly about teaching earth pigment paint making workshops. I’m always amazed how the act of picking up a rock, breaking it down into dust, and turning it into paint speaks to people in ways I don’t fully understand.

This summer, the Taos Art Museum is exhibiting Baer’s first solo museum show Moon Horse and Sky, featuring a collection of Western mystic oil paintings made from earth and mineral pigments. The show “seeks to hold our interwoven relationships with the land, horses, moon, and sky and looks at the relationship between how we see women and how we treat land, between memory and cosmology, in paintings made from dirt and rock, in the earth pigment bodies of women and children riding birds and horses at sunrise.”

Baer’s parents moved to New Mexico when she was four. Her mom had a leopard appaloosa she owned with a friend, a white horse with black spots, named Mable. When Baer was in high school, her mother had a pinto named Virgil. Baer’s mother is still living, but has late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. “When we moved back to Santa Fe in 2020, my mom still recognized me,” Baer said. “But by the end of that year, she didn’t know who I was anymore.” Baer and her husband, a designer named Seth Reese, bought a little ranch south of Santa Fe, and moved in with their three young children, Wyeth, Whitman, and Winona. They named their place Moon Horse Ranch, after a dream their firstborn child had when he was two of a horse with moons on its back. Their vision for the ranch is “to be a place where people draw closer to the land, one another, and themselves.” They do this by offering workshops on Earth Pigment Paint Making taught by Baer, where she teaches how to gather in ways that are in relationship with the land rather than extractive, and encourages people, wherever they are, to honor and learn more about the living history of Indigenous peoples. Moon Horse Ranch also offers workshops taught by their artist friends: Moon Photography by Tyana and Lapita Arviso, Fleece Spinning and Natural Dye by Sara Buscaglia, and Quilt Making by Maura Grace Ambrose.

Baer feels haunted by the absence of her mother in her life and work. “I often think of a poem by Nayyirrah Waheed,” she says. “‘My/ mother/ was/ my first country;/ the first place i ever lived.’” She raises her children with certain elements of her childhood, a world she shares on Instagram that is peculiarly her own. “Before Moon came to us, I had been praying for a leopard Appaloosa for about twenty years,” Baer says.

Two years ago my husband’s sister Morgan found Moon’s listing at a kill pen in Texas. She was just a number. At first I wasn’t sure we could afford to buy her but that weekend I sold several moon paintings and we bought her the day she was scheduled to ship to slaughter. She was very thin and malnourished when she arrived but with time and love and wild grasses she regained her health. Our son Wyeth named her Moon and Stars. This past February we rescued a six month old baby pinto from a kill pen in northern New Mexico and named him Sky. He was taken from his mother and herd so he has been slow to trust. After several months of working with him every day he is finally letting me place a halter on his nose and rub the blaze between his eyes, which feels like a miracle.

The first time Baer brought a halter to the baby pinto, he tried to run through a fence. After several months of working with him, she can now offer little bites of food and he will allow a halter to gently perch on his brown and white nose and then fall off. She pauses, and the pinto asks for more. She places her hand on the halter so he has to move through the leather strap to receive the treat from her hand, and he learns the leather won’t hurt him. “Horses have a way of calling me back to myself and back to my body,” Baer notes. In one of Baer’s photographs, she places her hand on the golden straw-like mane of her appaloosa, whose life was not discarded but seen as holy.

Santa Fe is a high-altitude city, sitting almost 7000 feet above sea level. There, the sky is wide and unobscured by the trees. One thing we kept returning to in our conversations is how important it is to be honest about the hard work of caring for animals and running small businesses, and not romanticize the way of life they’ve chosen. Baer and her husband, Reese, work long days taking care of the three children, the animals, running three small businesses during a very difficult few years for small businesses, fixing fences, shoveling manure, tending the garden, trying to make it all work. She says,

some days are very difficult, especially when I’ve been up all night with a sick child, or a sick goat, or a horse with colic, or howling coyotes, or working on a painting I can’t get out of my head, or a studio work deadline. Our house is never clean and the laundry is never folded. Learning to care for animals in sickness and in health can be daunting. Hay and gas and food are all so expensive. But I’m so thankful this is my life, for the chance to raise our children with horses and goats and this land. I’m thankful to be a painter and photographer and to help provide for my family in this way. I’m so grateful I can make a living doing something I love, something grounded in the earth, making paintings and teaching others how to make paint from the land. Being a mother, wife, and artist is not easy but nothing worth doing is easy. Like a seed planted in the ground, each of these ways of being asks us to let go, die to ourselves, and let ourselves be reborn.

Their sheepdog has initiated a friendship with the pinto, and their middle child, Whitman, is building a collection of his own earth and mineral pigments he smashes on the front porch. The sky and the land work together across the seasons, bringing life and snow to their garden and the mountains around them.

Baer’s favorite time of day is the early morning. She gets up with the crepuscular creatures of the ranch and tends to the animals. While she works with the horses, the Belt of Venus is above her, that phenomenon in which a backscattering of atmospheric light creates a gradation of blue to purple to pink to yellow to blue. The Belt of Venus is found in all the paintings in Moon Horse and Sky, and the land and horses are painted with a softness, “a dissolving of focus, a blur more true to how the eye sees light.”

Each painting in Moon Horse and Sky comes from a listening practice Baer cultivates. It’s not always clear to her why she’s making a painting, but somehow, in following her visions, the various paintings of the show have ended up in conversation with one another. Life with the appaloosa, Moon, is shown at various moments, up close and at a distance. The viewer gets a sense of Baer’s intimate relationships with the creatures she cares for, as each painting holds a particular moment in the life of the animals. In one painting, the pinto looks shy and timid, because it was made when he first arrived at Moon Horse Ranch. But in the later paintings of Moon Horse and Sky, the pinto is moving freely with Moon under the western sky. Baer has been documenting the baby pinto’s changes almost every day on Instagram, his fear slowly giving way to play and what she calls a sacred trust.

The blues of Moon Horse and Sky are worthy of mention. Baer uses a shockingly blue pigment the same color of the mountain bluebirds at Moon Horse Ranch. In one painting, her daughter Winona rides on the back of a bluebird, “a picture of the bittersweet loss of watching your children grow out of the baby years. It almost feels like they’re riding away from you on the backs of wild animals. The mountain bluebirds were my mother’s favorite bird,” says Baer. “They don’t look real when you see them. They’re arresting to the eye, and their color and sounds startle me into a space of contemplation and prayer. I think of them as messengers of joy.”

Birds have long been a way Baer has received messages from beyond herself. When she first began to paint, she painted a bird a day for Lent. In a recent painting of Moon, the horse stands against the Belt of Venus, accompanied by a mourning dove. Baer painted them together after another one of their horses, Sun, died of colic last summer. “I painted that dove over Moon, because after Sun died, Moon would call for him, alone in the fields of wild grasses,” Baer says. In another painting, a crow flies over Moon like a specter, a living symbol of death and trickery. “The crows in the field make the strangest noises,” says Baer. “They always remind me of our culture’s refusal to face death. I know that refusal is at the root of so many ills. When we care for animals we are faced with death, and we must honor death like we do grief.” After their horse Sun died, Baer and her family scattered his ashes in their garden. Their children still speak of him often, and one of the paintings in Moon Horse and Sky is of Sun, standing in the field.

Several years ago, Baer was lying in bed, nursing her daughter, Winona. She looked out the window and saw the Belt of Venus. She longed for her mother to know her baby, whom she never met. Baer began to paint a new large cotton canvas, with an image of her mother riding Moon, adding her presence to the landscape that was empty without her. Baer painted her mother wearing her grandmother’s cloak, but changed the color to the bright blue shade of a mountain bluebird, the color of the Virgin Mary’s blue robe. “A color of infinite love,” says Baer. “My mother was my source. I want to cloak her in the stars.” This painting, titled “Our Lady of the Horse,” is currently on display at Taos Art Museum. Baer says,

I used my own body as a model for the body for the painting, but my mother’s face. When I’m on the horse, when I’m on Moon, there’s a sense that I’m embodying and living out the joy that my mother experienced with horses and with me that lives on in me. Her joy lives on in me. The closest thing I have to her is her joy within me. And of course it’s interwoven with the grief of her not being here, and how I wish she was, and how she’s been in pain for so many years, and how I long for her to be in peace. And the paintings are circling around that grief like the moon. Going to canyons to find dirt and make pigments, I was looking for her in the places she was with me as a child, even though I knew I’d never find her. Going down the roads she used to walk I just wanted to be close to her. When I’m with the horses, I find her.

Alice Courtright is a poet and writer living in New York. She thinks about literature, dance, grace, and the natural world. Alice has received degrees from Yale University, Sewanee’s School of Theology, and Yale Divinity School. She is ordained in the Episcopal Church, and her writing has recently appeared in The Hedgehog Review, Mockingbird, and SAGE Magazine. She lives with her husband, Drew, a parish priest, and their three daughters, about an hour north of the city. Read more at alicecourtright.com.

Images

1. The Appaloosa, Baby Pinto, and the Bluebird 2024 Earth and mineral pigments and walnut oil on cotton 22 x 28”

2. Earth and Mineral Pigments collected on a edge of a highway near Abiquiu, New Mexico (photograph)

3. Baer painting in the field at Moon Horse Ranch under the Belt of Venus (photograph)

4. Baer’s painting their appaloosa named Moon in the field at Moon Horse Ranch

5. Baer’s hand on Moon (photograph)

6. Baer painting the Belt of Venus with her daughter Winona (photograph)

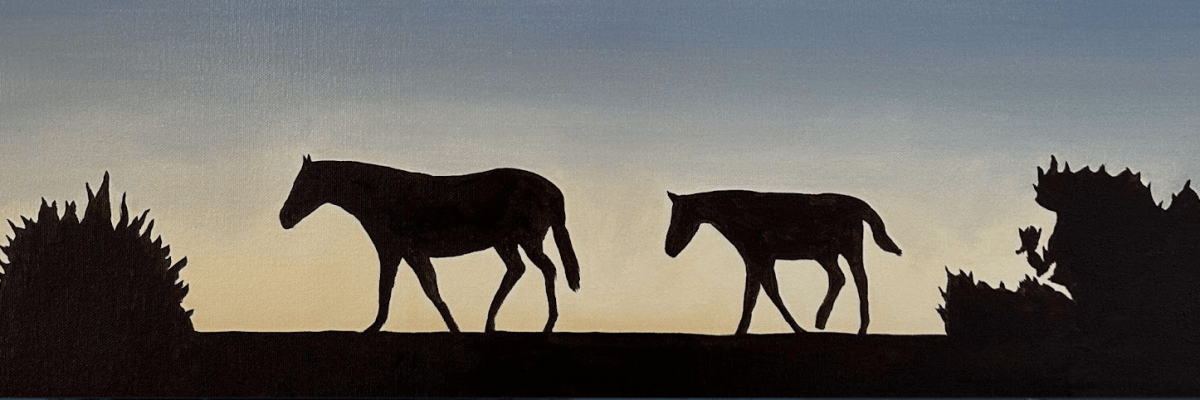

7. Moon and Stars and Sky 2024 Earth and mineral pigments and walnut oil on cotton 22 x 28”

7. The Appaloosa and the Crow 2023 Earth and mineral pigments and oil on cotton canvas 18 x 24”

8. The Appaloosa in the Field of Wild Grasses 2023 Earth and mineral pigments and oil on cotton canvas 18 x 24”

9. painting Our Lady of the Horse in the studio (photograph) 2024 Earth and mineral pigments and walnut oil on cotton 64 x 81”

Categories: art, featured, featured artist, featured photographer, Nature

This was very interesting. And well written in words, descriptions, photographs and paintings. Beautiful. -Ahj

LikeLike