By Arthur Davis

一時雨礫や降つて小石川

Matsuo Basho, 延宝5年, the 5th year of the Enpo era, Edo, 1678-9

hito shigure/ tsubute ya futte/ Koishikawa

at this moment, it is sleeting

and hailstones are falling all about,

at Koishikawa

To which, Bashō no yōna says:

All about me, it’s sleeting

Bashō no yōna, Wichita, January 2022

I’m freezing, only thinking

Fame is fleeting

To which Matsuo replies:

So is life

Matsuo

Edo, Winter, 1678-9

Matsuo had arrived in Edo, in 1675, seeking fame and fortune as a haiku master. He resided near Edo’s glitzy Nihonbashi District, a country boy in the big city that Edo was becoming. And he was variously employed, making ends meet, while honing his poetic skills. By the winter of 1678-9, he had achieved some recognition.

An admirer of Buddhism, Matsuo would be thinking, fame does not come to all, to those who are lucky, fame is fleeting, for we are only here for a short while — yi shi, 一時.

Fame was in the Future

Matsuo had not, however, taken on the pen name Matsuo Basho. This would occur after 1680 when he moved to the Fukagawa District of Edo and lived in a simple cottage beside a banana tree given to him by a student. Nor had Matsuo taken his journey to the northern interior, which would give him lasting fame in the posthumous publication of Oku no Hosomichi (奥の細道).

For was, now, simply living in the moment, yi shi, 一時.

Notes on Translation

Hito, 一時, Chinese, yi shi, meaning at this time, for the moment, not necessarily a concrete moment, a spiritual one; also a Buddhist term for a period in which one chants a sūtra.

Shigure, 雨, a freezing rain, drizzle, sleet, referring to the rainy season in late fall and early winter.

Futte, 降つて, falling about. Matsuo is also implying that he is about to experience a change of fortunes, either for good or bad.

Koishikawa, a place in Edo (Tokyo), a well-known garden constructed in the early Edo period, possessing a view of Mt. Fuji. Koishikawa, meaning small river pebble. Basho’s haiku is a play on words with hail as the small pebble. It is also a Buddhist observation of the insignificance of one moment and one man in the eternity of time and space. Matsuo, at this time was engaged in work on an aqueduct, which may explain the connection with the construction of the garden.

Basho on Snow and Winter

From the book Oi no kobumi, Winter 1687-8:

いざ行かむ 雪見にころぶ 所まで

Iza yukan / yukimi ni korobu / tokoro made

Let’s go out

And see the snow

Until we slip and fall.Matsuo Basho, Oi no kobumi, Winter 1687-8

A child grows up and the snow is not his friend. Still, snow on Mt. Fuji is a thing of beauty.

一尾根はしぐるる雲か 富士の雪

hito one wa / shigururu kumo ka / Fuji no yuki

over the ridge

Winter showers

is there’s snow on Mount Fuji? Matsuo Basho, Oi no kobumi, early Winter 1687-8

Oi no kobumi

In English, Notes from my Knapsack, or Backpack Notes, 笈の小文, October 25, 1687 to June 1688. Matsuo Basho was 44 when he began this round-robin trip, reciting verse, from Edo to Iga, then Nagoya, to the grand Ise shrine, and from Nara to Otsu, and home again. Like a child going to school, he carried a knapsack, oi 笈, usually made of bamboo.

Snow on Mt. Fuji

There are many translations of Matsuo Basho’s haiku. Not surprisingly they do not all agree. Many a slip twixt the cup and the lip, said Robert Burns. In our case, between the pen, the word, and the ear.

In the last haiku, being away from Edo, I suspect Matsuo was wondering if the snow had yet appeared at Mt. Fuji. In late fall, snow flurries make their first appearance at Mount Fuji. And, typically, Fuji is snow-capped five months out of the year. Traveling by horse over the hills in a winter storm, wondering is there snow on Mt. Fuji. This question arises because the character か, ka appears prior to snow on Mt. Fuji (shigururu kumo ka / Fuji no yuki).

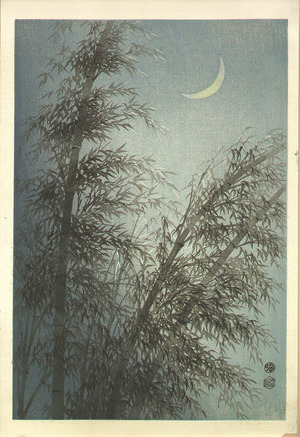

Winter’s Garden, 冬庭や

a wintry garden, a silvery thread,

ah, the moon,

as insects hmm …fuyu niwa ya

tsuki mo ito naru

mushi no gin冬庭や 月もいとなる むしの吟

2nd year of Genroku, at a tea ceremony with Ichinyū celebrating Banzan.

Winter, 2nd year of Genroku, 1689

At least one modern-day student of Basho dates this haiku to 1689 and adds, “on meeting Ichinyū at a celebration held by Banzan.”

Ichinyū was a lay Buddhist teacher and seven years Basho’s senior. By trade, he was a traditional tea potter, fourth generation Raku. Ichinyū lived and worked in Kyoto, which suggests that he was an old friend from Basho’s student days.

Kumazawa Banzan was a follower of Confucius, an advocate of agricultural reform who ran afoul of the Shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. Beginning in 1687, Bashanwas confined to Koga Castle in Ibaraki Prefecture, making it likely that the occasion for writing this haiku was not a meeting with Banzan, but a celebration of Banzan’swritings that took place at a tea ceremony in Kyoto hosted by Ichinyū.

We should perhaps give Basho credit here for political commentary. I read this haiku as, “the peasants (i.e. insects) continue through winter’s darkness to work (hmmm) for the Imperial court and the samurai class.

Notes on this haiku

The 2nd year of Genroku refers to the reign of Emperor Higashiyama.

Those who garden know that a winter’s garden, fuyu niwa ya, 冬庭や, has but a few plants and fewer insects. The ending character や, ya, turns this phrase into an interjection expressing surprise which I’ve added to the next line. An early frost shrivels the leaves and stills the sounds of the insects who feed on the plants. To me, it is remarkable after an early frost to hear a solitary insect humming. This insect has perhaps burrowed down deep in the earth, found a dung hill, or huddled next to the house to survive the icy cold. And the next day, in the warmth of the sun, merrily goes about its work.

Tsuki mo ito naru. Tsuki is our familiar moon in all its phases. Naru is the verb form for becoming. Mo ito, literally, like a thread, giving us the sense that the moon is waning to a “silvery thread.”

Mushi no Gin, the sound of insects. I render this as “insects hmmm.” Those familiar with Matsuo Basho’s haiku know that as a Zen poet, he was fascinated with the sound of things, whether it was a cricket under a helmet, a frog jumping in an old pond, or insects in rocks.

Toki Wa Fuyu

” 時は冬.” Toki wa fuyu, the season is winter. How cold is it? On cold winter days, it is not just me, even my shadow is frozen.

冬の日や馬上に氷る影法師

fuyu no hi ya bajō ni kōru kagebōshi

these cold winter days

on horseback

— my shadow is frozenMatsuo Basho, Oi no kobumi, Winter 1687

On the Tokaido

From Oi no kobumi, on the Tokaido, en route to Cape Irago, riding on a particularly long stretch between snow-covered fields and the bitterly cold sea. Things on Basho’s mind include things from the past — Saigyo’s waka, Sogi’s renga, Sesshu’s landscape painting, and Rikyu’s Way of the Tea; those and the bitter cold.

One of the reasons for reading Basho’s haiku is that they give us “an alternative possibility of being.” (Jane Hirshfield, Seeing Through Words: Matsuo Bashō, interpreting Oi no kobumi)

Notes on Translation

Tokaido – the eastern coastal sea route from Edo to Kyoto. The 19th-century artist Utagawa Hiroshige painted the 53 stations of the Tokaido.

Fuyu no hi – winter day, on cold winter days, fuyu no hi ya, where ya is added for emphasis.

Koru – frozen; Kageboshi – shadow

Read more of Arthur Davis’ thoughts on Matsuo Basho’s poetry here.

Thank you

LikeLike