I am not writing this as a scholar of Russian literature or of French philosophy, and certainly not as a theologian. This is more of a testament to the fact that we can be deeply moved by something, even changed by it, in ways the author probably never intended and could not have foreseen. “…perhaps you won’t understand what I am saying to you, because I often speak very unintelligibly, but you’ll remember all the same and will agree with my words some time.”

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus states that Alyosha, one of the Brothers Karamazov, can’t be a truly absurd character because he has hope. Specifically, he has hope of meeting loved ones again in Heaven after death. Camus tells us that Dostoevsky writes in his diary, “If faith in immortality is so necessary to the human being (that without it he comes to the point of killing himself), it must therefore be the normal state of humanity. Since this is the case, the immortality of the human soul exists without any doubt.” And Camus says of Dostoyevsky, “Then again in the last pages of his last novel, at the conclusion of that gigantic combat with God, some children ask Aliocha: ‘Karamazov, is it true what religion says, that we shall rise from the dead, that we shall see one another again?’ And Aliocha answers: ‘Certainly, we shall see one another again, we shall joyfully tell one another everything that has happened.'”

Camus is disappointed, in part because he feels Dostoyevsky is betraying his own past success of creating one of the few truly absurd characters in literature: Kirilov from The Possessed, who kills himself “in order to assert my insubordination, my new and dreadful liberty.” As Camus tells it, “If God does not exist, Kirilov is god. If God does not exist, Kirilov must kill himself. Kirilov must therefore kill himself to become god. That logic is absurd, but it is what is needed.” But in the character of Alyosha and in Alyosha’s assurance that we will meet again after death, all of this is negated, “Thus Kirilov, Stavrogin, and Ivan are defeated. The Brothers Karamazov replies to The Possessed.”

Of course, Dostoyevsky wasn’t trying to create a truly absurd character. He was working with and subverting other, earlier literary expectations. And what makes Dostoyevsky an enduringly great artist, to me, is that he was writing what he had to write in order to understand what he believed, to work through his own doubts and demons. As Camus tells us, “Dostoevsky wrote: ‘The chief question that will be pursued throughout this book is the very one from which I have suffered consciously or unconsciously all life long: the existence of God.'” Where I differ from Camus in my understanding of Dostoyevsky’s writing, is that I’m reading it as someone with different doubts and demons than are echoed in Camus’ words, adjacent to them, but leaning more towards the humanity of Alyosha’s character than the theology of it.

Alyosha is undeniably a spiritual character. If Ivan is the mind and Dmitri is the body, Alyosha is the soul. But as I read it he’s spiritual in the way that anyone alive who thinks and doubts and loves is spiritual. Even as Camus himself is, in the very act of writing The Myth of Sisyphus. In some ways, I think the character of Alyosha was a gift from Dostoyevsky to himself, a pure but very human creation who stands aside from any cynicism or is an answer to it. Alyosha was named after Dostoyevsky’s own son, who died as a child, and I’m not the first to think that the character is a sort of embodiment of the man Dostoyevsky might have hoped his son would become. He’s handsome, kind, good but not preachy, thoughtful, sympathetic. He’s not cloyingly good, because, strangely, despite all of his ridiculously good qualities, he’s a very real and human character. He’s full of wonder, he’s often confused, his mood shifts from one sentence to the next, as we’ve all felt our own do.

He’s part of the drama, obviously, he’s one of the brothers Karamazov, so he’s a major character, but he’s aside from the drama, except that it becomes his job to solve the problems his brothers create. Most of his own struggles are internal – they’re philosophical or spiritual. He has faith, but he’s constantly questing and questioning, swayed by his cynical brothers, but very strong within himself. In a sense his very existence questions not just the morality of the people around him, but the morality that drives the plot itself. His journey in the novel feels like a difficult but natural peeling away of layers of accepted corruption and violence eternally present in the world.

Camus famously concludes The Myth of Sisyphus by saying, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” and in his telling of the myth of Sisyphus, I can only see the story of Alyosha himself. Camus describes the various versions of the myth that explain why Sisyphus was punished in the first place, and they all involve conflict, strife, misunderstanding, pettiness, greed. And so did Alyosha’s life: From youth he had to live with or untangle the atrocities of his hideous father and the dramas of his madly passionate brothers. This moment, the moment that Alyosha addresses the boys at the funeral of their young friend, is that exact moment that he pauses in carrying his burden, and feels something bordering on joy. For Camus, “It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me … I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour is like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.”

In a sense, for Alyosha, hope — creating it, sustaining it, spreading it — is a boulder, a burden, and a never-ending task. At the funeral, Alyosha tells the boys, “Boys, we shall soon part. I shall be for some time with my two brothers, of whom one is going to Siberia and the other is lying at death’s door. But soon I shall leave this town, perhaps for a long time, so we shall part. Let us make a compact here, at Ilusha’s stone, that we will never forget Ilusha and one another.” He will go back to caring for his brothers, but for now, this is an hour of consciousness. And, to me, he speaks less of heaven and more of memory as a way to preserve the “immortality of the human soul,” in this passionate outpouring:

And whatever happens to us later in life, if we don’t meet for twenty years afterwards, let us always remember how we buried the poor boy at whom we once threw stones, do you remember, by the bridge? and afterwards we all grew so fond of him. He was a fine boy, a kindhearted, brave boy, he felt for his father’s honour and resented the cruel insult to him and stood up for him. And so in the first place, we will remember him, boys, all our lives. And even if we are occupied with most important things, if we attain to honour or fall into great misfortune-still let us remember how good it was once here, when we were all together, united by a good and kind feeling which made us, for the time we were loving that poor boy, better perhaps than we are. My little doves let me call you so, for you are very like them, those pretty blue birds, at this minute as I look at your good dear faces. My dear children, perhaps you won’t understand what I am saying to you, because I often speak very unintelligibly, but you’ll remember all the same and will agree with my words some time. You must know that there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life in the future than some good memory, especially a memory of childhood, of home. People talk to you a great deal about your education, but some good, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if one has only one good memory left in one’s heart, even that may sometime be the means of saving us. Perhaps we may even grow wicked later on, may be unable to refrain from a bad action, may laugh at men’s tears and at those people who say as Kolya did just now, ‘I want to suffer for all men,’ and may even jeer spitefully at such people. But however bad we may become — which God forbid — yet, when we recall how we buried Ilusha, how we loved him in his last days, and how we have been talking like friends all together, at this stone, the cruellest and most mocking of us — if we do become so will not dare to laugh inwardly at having been kind and good at this moment! What’s more, perhaps, that one memory may keep him from great evil and he will reflect and say, ‘Yes, I was good and brave and honest then!’ Let him laugh to himself, that’s no matter, a man often laughs at what’s good and kind. That’s only from thoughtlessness. But I assure you, boys, that as he laughs he will say at once in his heart, ‘No, I do wrong to laugh, for that’s not a thing to laugh at.’

This is a different kind of morality — a memorial morality — explained in great excitement by a man who has been around selfishness and cruelty all of his days, and sees, if only for this moment, this breathing-space, a way out of it. Dostoyevsky says that when “Aliocha clearly says: ‘We shall meet again.’ There is no longer any question of suicide and of madness.” But I think Alyosha is half-mad here, afflicted with the same fever that his brothers are, though theirs is of the mind and body, and his is of the soul, whatever that may be. “Certainly, we shall see one another again, we shall joyfully tell one another everything that has happened.'” Alyosha answered, half laughing, half ecstatic.

Clearly, you could think about any of this in religious terms, and many people, including Camus, have written about it in this way. But I see it instead in human terms, except insofar as religion is an expression of human needs and fears. As much as The Brothers Karamazov is about faith, it is also about cruelty, very human cruelty. For Alyosha memory and hope are paths away from that. The boys mourning their friend once tormented him and threw rocks at him, until Alyosha showed them all kindness. Earlier in the novel, Alyosha tells his friend, “Do you know, Lise, my elder told me once to care for most people exactly as one would for children, and for some of them as one would for the sick in hospitals.” And, sadly, as we have seen again and again in history and even to this day, religion often tells us that other people’s children, even their sick children, are not worth caring for or even mourning. But as humans, who might not need a promise of heaven but certainly need some small sense of hope every day of our lives, and need some reminder to care for one another, it is important to remember Alyosha’s words.

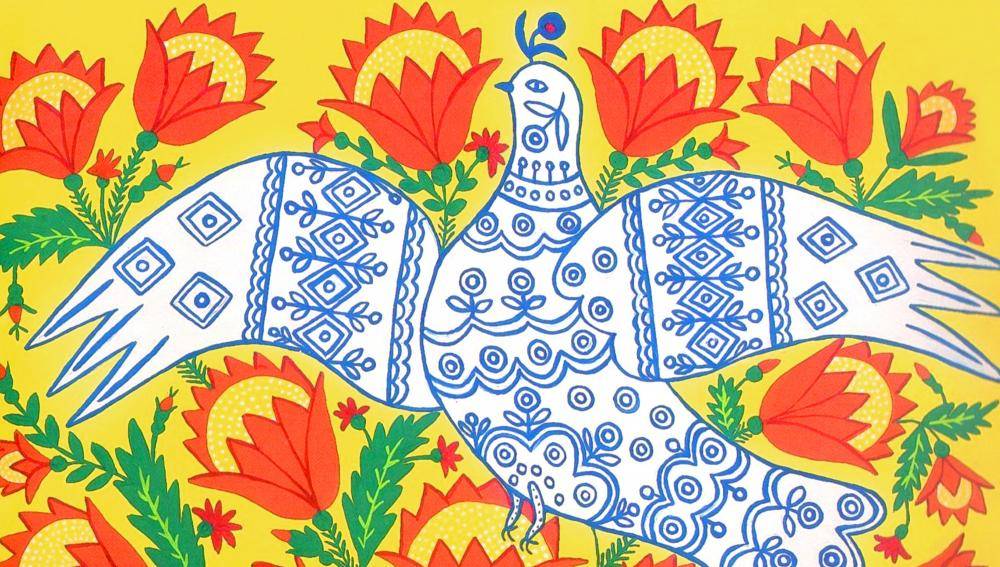

A Dove Has Spread Her Wings and Asks For Peace. By Maria Prymachenko.

Categories: featured, literature

1 reply »