By Roy Pedersen

(This article is an extract from Roy Pedersen’s book Jersey Shore Impressionists: The Fascination of Sun and Sea 1880-1940.)

Clara Stroud worked to create opportunities for all women to exhibit and promote their art. Clara was a leading exponent of women’s suffrage. She fought for women to have the right to retain their name after marriage. In 1919 Pratt Institute hired Clara and insisted she use her married name. Clara refused and hired Rose Bres, President of The National Women’s Lawyer Association. After a legal fight, Pratt relented and Clara is credited for creating the right for women to sign their names to their works of art.

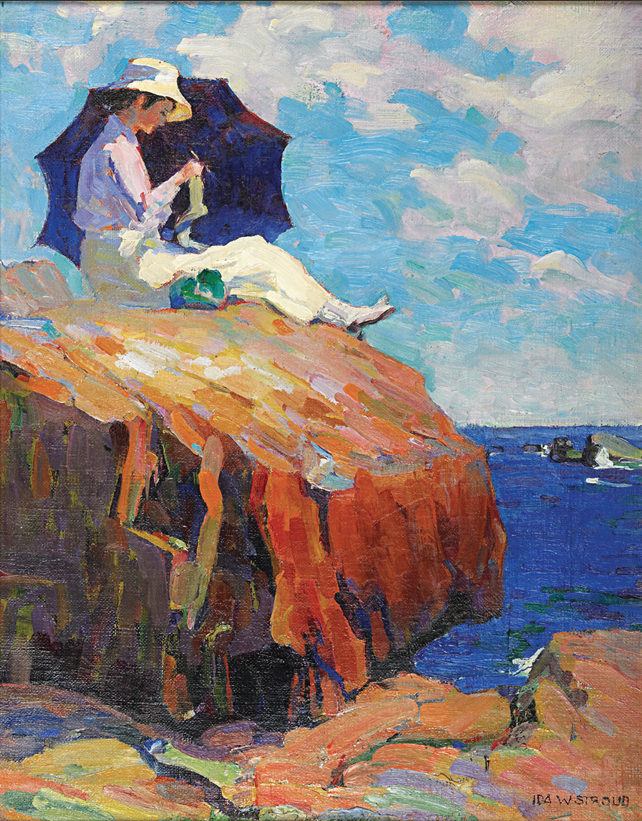

Ida Wells was born in New Orleans in 1869. In 1888 she married George Stroud and in 1890 gave birth to her daughter, Clara Stroud. Throughout their lives, Ida Wells Stroud and Clara Stroud together created a distinguished body of work spanning more than sixty years. It is hard to consider their careers separately. Beyond the usual close relationship of a mother and a daughter, their lives frequently intersected and many times the experiences of one would be repeated by the other. Both enjoyed only a brief period of marriage and a lifelong devotion to art. Their art drew from the ideas of their times and reflects their singular rich capabilities as artists.

Ida Stroud’s early artistic development must be placed within the context of events that occurred in New Orleans during the last two decades of the 19th century. These events inspired and liberated women from the more traditional choices available to them. Ida’s decision to become an artist and her forays into woodcarving, pottery, and design, all have their origins in her experiences in New Orleans.

In the late 19th century, New Orleans presented young women with new opportunities to create lives in the arts and to advance the cause of women’s suffrage. In 1884 and 1885 New Orleans hosted the Cotton Exposition World’s Fair. Events that took place within the fair encouraged women to consider new roles for themselves. Women from all over the United States sent in exhibitions to the Women’s Department, and a series of lectures regarding new ideas in the practice of fine and decorative arts were presented. The exhibitions included painting and wood carving, both later taken up by Ida Stroud. Those present at the fair received a strong dose of the ideals and efforts of the Woman’s Suffrage movement through its involvement with the emerging Arts and Crafts Movement. Female artists were exposed to the work of other female artists, and to the newly developed ideas regarding the teaching of art education that strongly stressed the creative work of women.

Immediately after the Cotton Exposition, Tulane University organized free evening and Saturday drawing classes in New Orleans. The classes were enthusiastically received and continued for ten years with a total enrollment of more than 5,000 students. The classes for women met once a week on Saturdays, and the decorative arts class met two nights a week. The Tulane Decorative Art League developed as an outgrowth of these evening decorative arts classes for women.

In 1886 Newcomb College, the women’s college of Tulane was founded with a gift from Josephine Louise Newcomb. The aim was to give young women the same opportunities for a liberal education that were available to young men. The free evening classes continued as well. Woodcarving class was later included and produced excellent results under Ben Pitman, who had earlier been the creative catalyst for a whole generation of female woodcarvers through his courses at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. Local pottery enterprises were included as well, with George Ohr and Joseph Meyer, who produced the clay bodies decorated by the women taking the classes.

In 1894, when Ida Stroud’s husband George died, she moved north with full resolve to continue her art education and become an artist.

Pratt Institute had begun in 1887 as a manual training school for the applied arts. By 1893, many of the departments at Pratt sent exhibitions to the Chicago World’s Fair. The presence of women in the arts was conspicuous at the fair and highlighted their role in the rapidly developing Arts and Crafts movement. The World’s Fair included a Women’s Building filled with an international display of fine arts, crafts, and industrial designs that included contributors as diverse as Mary Cassatt and Queen Victoria. The Pratt Monthly (June 1893) reported; “There is no building that excites more curiosity and visitors than this.” It also proclaimed (October 1892): “This is the woman’s era.” By expressing these ideas, Pratt quickly became known as a “headquarters for liberal thought and advanced movements.” Throughout the 1890s Pratt shed its image as a trade school in exchange for an emphasis on art and design.

In 1895 Arthur Wesley Dow arrived at Pratt, bringing with him his radical new methods for integrating art and design through shared principles of composition. Pratt began to draw the brightest and most talented students of the period and was in the vanguard of art in New York City. Under the direction of Dow, whose revolutionary approach to art education was changing the face of American art, Pratt would come to be recognized as a leading institution for education in the arts. Dow emphasized a new way to create art outlined in his book Composition, which stressed the study of Japanese art, and he fostered a program of study that emphasized creativity, individual expression, and an appreciation of the beautiful. He was a founding member of the National Society of Craftsmen in 1906 and served as its vice president.

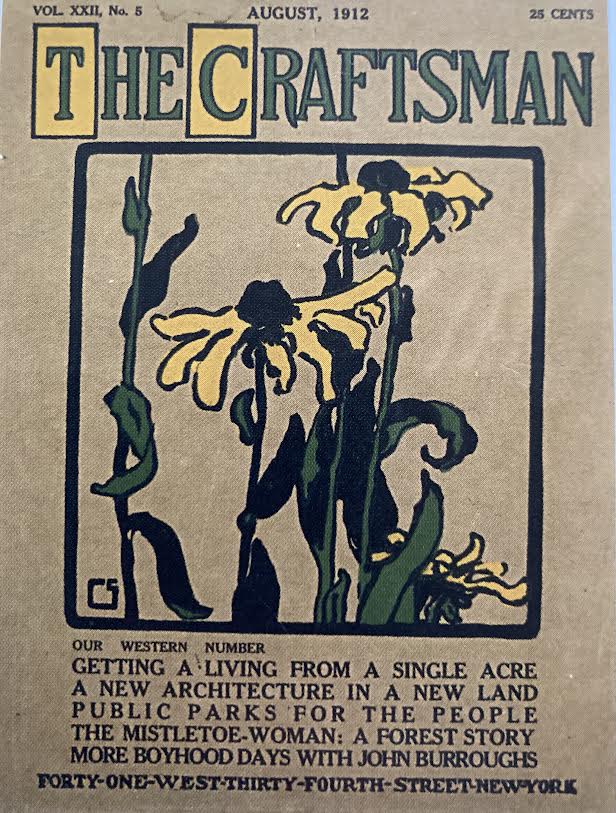

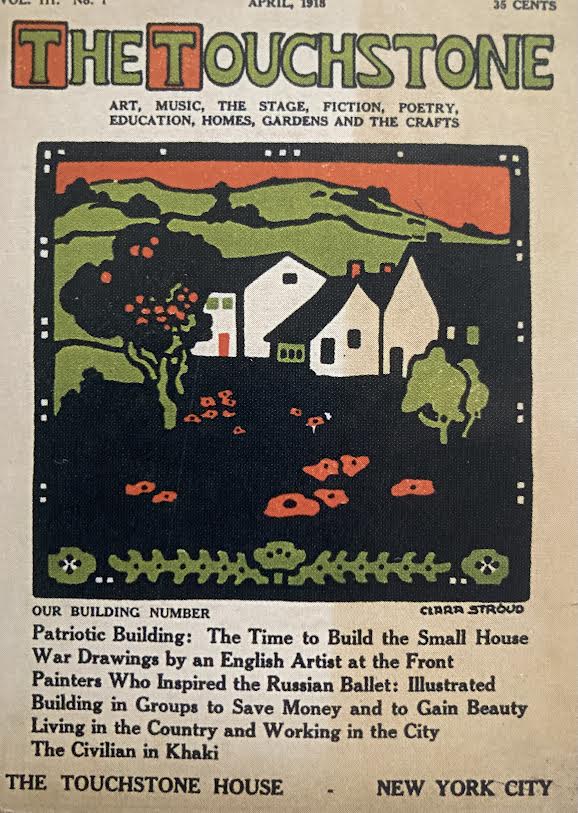

In 1898 Ida Stroud began to study at the Arts Students League with William Merritt Chase. She enrolled as a student at Pratt in 1900 and graduated in 1903. She continued her education in the postdoctoral program until 1907, teaching classes at Pratt from 1905 to 1907. Clara also graduated from Pratt having studied with Dow. The leading voice of the American Arts and Crafts movement was The Craftsman magazine, published by Gustav Stickley. Illustrations by Clara were chosen as covers for the August 1912 and October 1914 issues, and again for the December 1914 issue. Clara’s last cover for The Craftsman appeared on the February 1915 issue.

Ida Stroud spent most of her adult life painting and teaching in New Jersey. She taught at the Evening Drawing School, now known as the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts, until 1943. It began in 1881 as a small group of students who met on Sunday morning to sketch. The membership of the small group quickly became so great that it required additional evening classes that were sponsored by the city of Newark. Membership continued to grow rapidly, and soon more space and a larger faculty were needed. By 1907 the large enrollment demanded the addition of a second daytime instructor of design and wetercolor painting. Ida Stroud was hired to teach these classes and to supervise the overall management of the day classes.

In 1907 the civic importance of the school to the city of Newark was recognized and its name changed to the Fawcett School of Industrial Arts. Hugo Froelich, formerly the director of the Department of Design and Applied Art at Pratt, was installed as the new principal of the school. By 1930 the enrollment had grown to 1,500 and a new building was erected to house the school at a cost of $1 million. In 1936 its fine arts staff included John Grabach, Gustave Cimiotti, Maud Mason, Bernard Gussow, and Ida Wells Stroud. Her many years at the school ended in 1943 when she resigned because of her failing health. Her good friend and fellow painter Gustave Cimiotti, whom she had first met when they were both studying in New York at the Art Students League in the late 1890s and with whom she frequently painted during the summer months retired the following year.

On April 10, 1914, the Newark Evening News, in an article titled, “All out-doors is my Studio,” described an outdoor painting class conducted by Ida Stoud: “Equipped with paints, brushes, and various sorts and sizes of paper, and fortified by the spirit of art for art’s sake, half a dozen young women visited the Central Market yesterday. The aim of the visit was to get some local color for their pre-Easter work at the Fawcett School of Drawing and the sextet were students of the school taking advantage of the display of plant life at the market.” Soon a sizeable crowd formed around Ida and her students, became a nuisance, and interfered with their purpose. The article goes on to describe how police interceded with authority and “scattered the crowds that hindered art.”

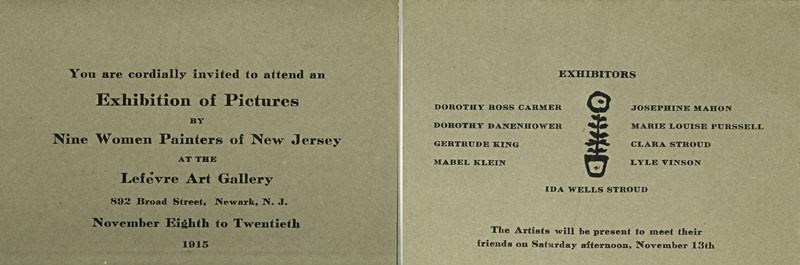

She was active in designing posters for the Women’s Suffrage Movement and also worked for public exhibitions for women painters. She formed a group from her former students, Nine Women Painters of New Jersey. In November of 1915, they held an exhibition at the LeFevre Art Gallery at 802 Broad Street in Newark. The group consisted of Dorothy Ross Cramer, Dorothy Dannenhower, Gertrude King, Mable Klein, Josephine Mahon, Marie Louise Purssell, Lyle Vinson, Clara Stroud, and Ida Wells Stroud. By November 1916 the group shrunk to seven members, consisting of most of the original group of nine and a new member, Josenia Elizabeth Larter. An exhibition of this group, “Paintings by a Group of New Jersey Women,” was held at the Recital Room of the East Orange Edison Shop on Main Street.

As well as taking her classes outdoors to paint in the Newark area, in the summer of 1916 she began taking her co-ed classes to Point Pleasant Beach to paint; there they stayed at the Jackson House. In 1924, Clara Stroud and her husband purchased a house and property in nearby Bricktown, New Jersey. Ida Stroud regularly taught summer classes in a studio built on the property.

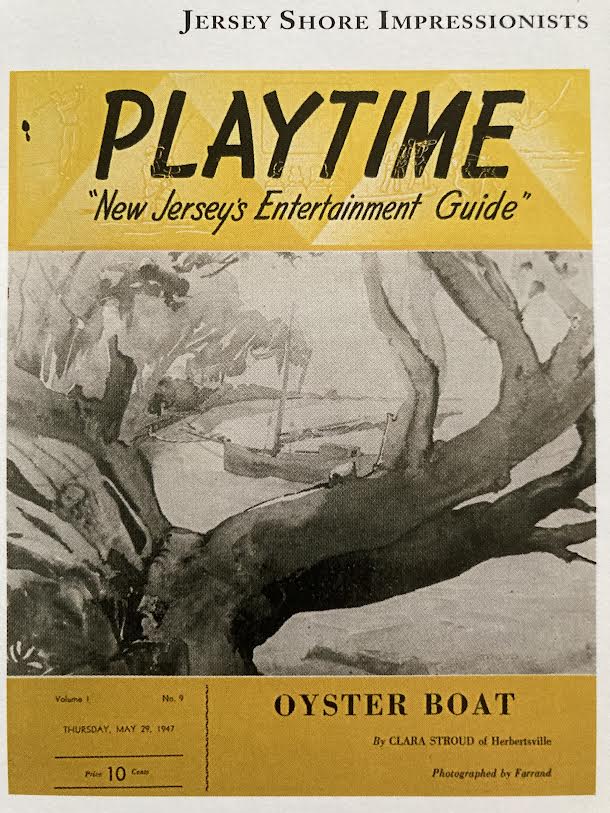

By 1930 Clara Stoud stopped painting in oil and committed herself fully to working in watercolor. “Watercolor has a freshness and vigor that seems to stand for America,” she wrote in her journal. Clara Stroud belonged to the largest association for women artists. She was an annual exhibitor at the American Watercolor Society. In 1950 she was invited to be the speaker at the membership exhibition that was held at the National Arts Club in New York City where she spoke of the success of her Barn Studio Summmer Exhibitions, held on her property in Bricktown.

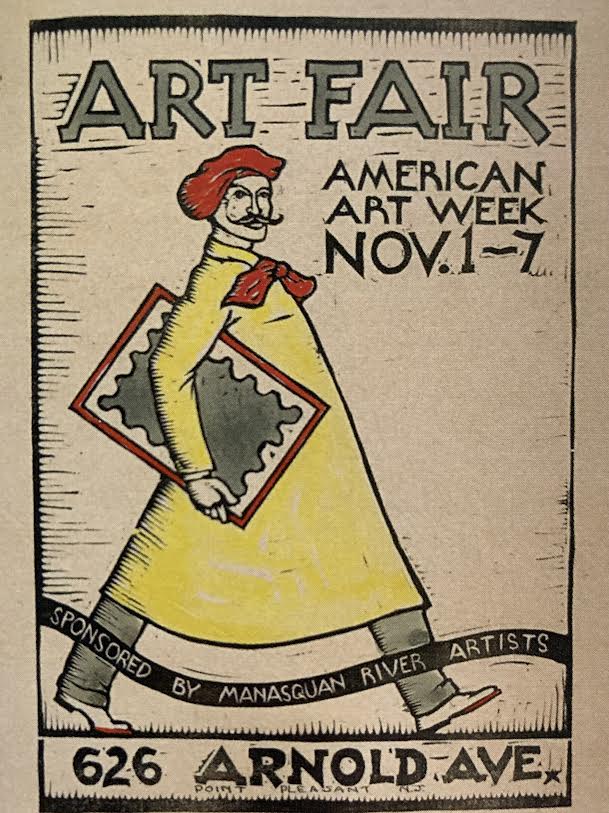

Beginning around 1924, Ida Wells Stroud held out-of-doors painting classes at Clara’s farm. From these classes, Clara developed a group to promote and celebrate American Art Week, a national annual event held November 1 – 7. In 1939 members of this group took the name “Manasquan River Group” since they all lived in the towns bordering the Manasquan. American Art Week was sponsored by the American Artists Professional League. For four summers, between 1921 and 1925, Ida Wells Stroud served as Professor of Design at the Summer School of Art at Syracuse University. At Syracuse, she resumed explorations in pottery that she had begun in the 1890s. She studied there with another form student of Dow, Adelaide Robineau, who ranked as one of the foremost ceramicists in the United States.

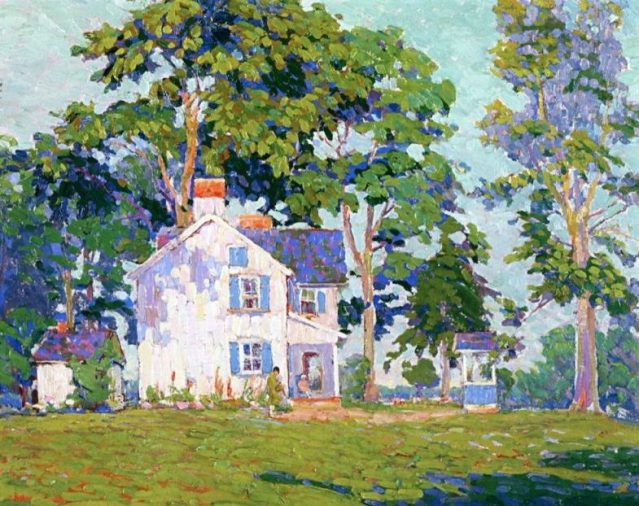

Meanwhile, in 1920 Clara and her husband, George Colvin bought the Herbert House, one of the oldest houses in Point Pleasant. Clara formed the Stroud Studio on the property and began to hold exhibitions and teach, often accompanied by her mother. Clara called the house “Five Miles Out,” referring to its distance from the ocean. George Colvin built a landing strip in the field behind the house, where he tested the navigational instruments that he was developing for aviation. The instruments were used by Charles Lindbergh for his historic transatlantic flight in May 1927. Lindbergh’s success brought great attention and sudden wealth to Colvin, who quickly became much in demand in California’s growing aviation industry. He and Clara divorced, and Clara received ownership of their home in Point Pleasant. Soon Ida Stroud was spending her summers at Clara’s house, and mother and daughter resumed their joint career, often painting and traveling together.

In the 1930s and 1940s other artists associated with the Newark art community traveled to the shore and produced works of strength and clarity. Henry Gasser, Frank Herbst, and Gustave Cimiotti are three such artists who brought the powerful images of the Jersey Shore into successful paintings produced during these summer visits.

For a time, Clara held the position of the first vice chairman of the New Jersey Chapter of the American Artists Professional League and played an important role in organizing its major exhibition held at the Hotel Warren in Spring Lake each summer. Clara was a frequent winner of awards at these shows, as well. Clara described her own work as “vigorous,” “crisp,” and “transparent.”She strived to create works with simplicity and pattern built with a strong harmony of color.

The lives of Ida Wells Stroud and Clara Stoud shone with their individual artistic talents, which earned them frequent prizes and awards in recognition of their accomplishments. In many ways, these two women embody the advancement in ideas that changed the role of women in the arts and informed much of the thought and practice of art in the 20th Century.

Roy Pedersen is an art dealer and historian in Lambertville, New Jersey, specializing in American Fine and Decorative Arts. He has lectured and written on the topics of modern painting, American pictorialist photography, woodblock prints, and the furniture of the Arts and Crafts movement. He has been featured in public television documentaries about the New Hope art colony, and in recent years has focused on the history of New Jersey Painting.

Jersey Shore Impressionists: The Fascination of Sun and Sea 1880-1940 by Roy Pedersen can be purchased here.