The photography of Mark Tamer is beautifully disarming. The images hit like small explosions that knock us off balance and make us question why we take photographs, how we see photographs, and how we see the world around us. We were grateful for a chance to ask him some questions about his process and his philosophy.

Magpies: One thing I always loved about film is the uncertainty. You could plan a shot, use light meters, etc, but there was always a sense of mystery and anticipation about what you’d see when the film was developed. With your chemigrams, it almost feels more like you’re creating a painting or composing the picture, but there’s still the feeling that the materials are unpredictable and the results will surprise you. Is there a different balance of control and chance in the various different processes you use?

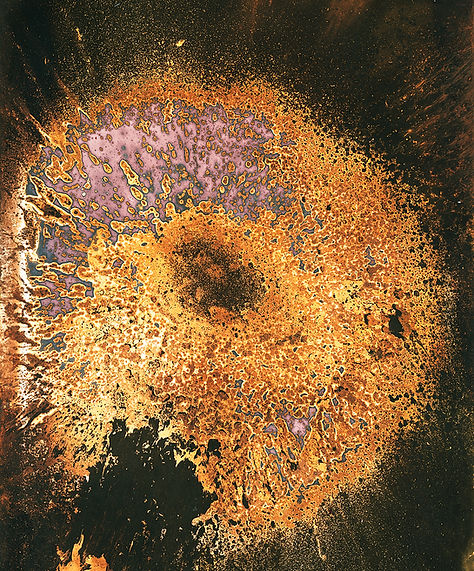

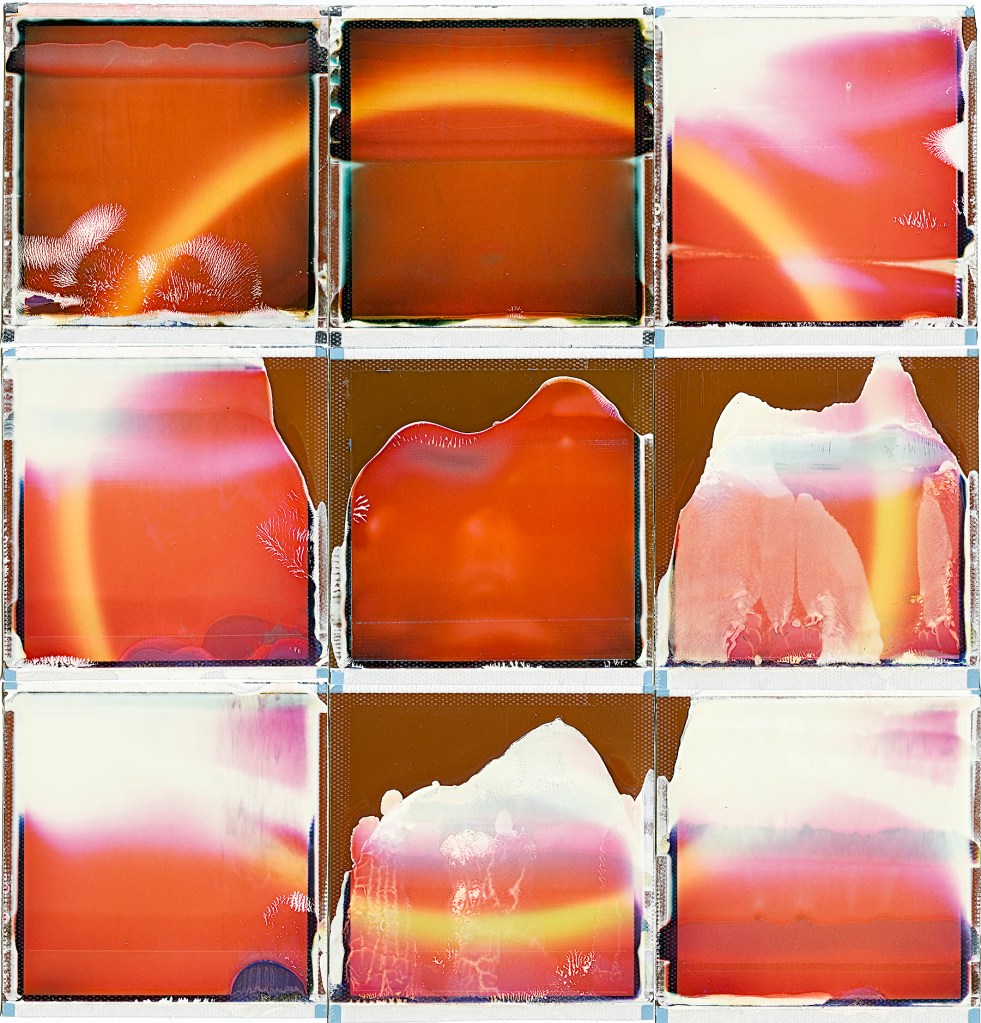

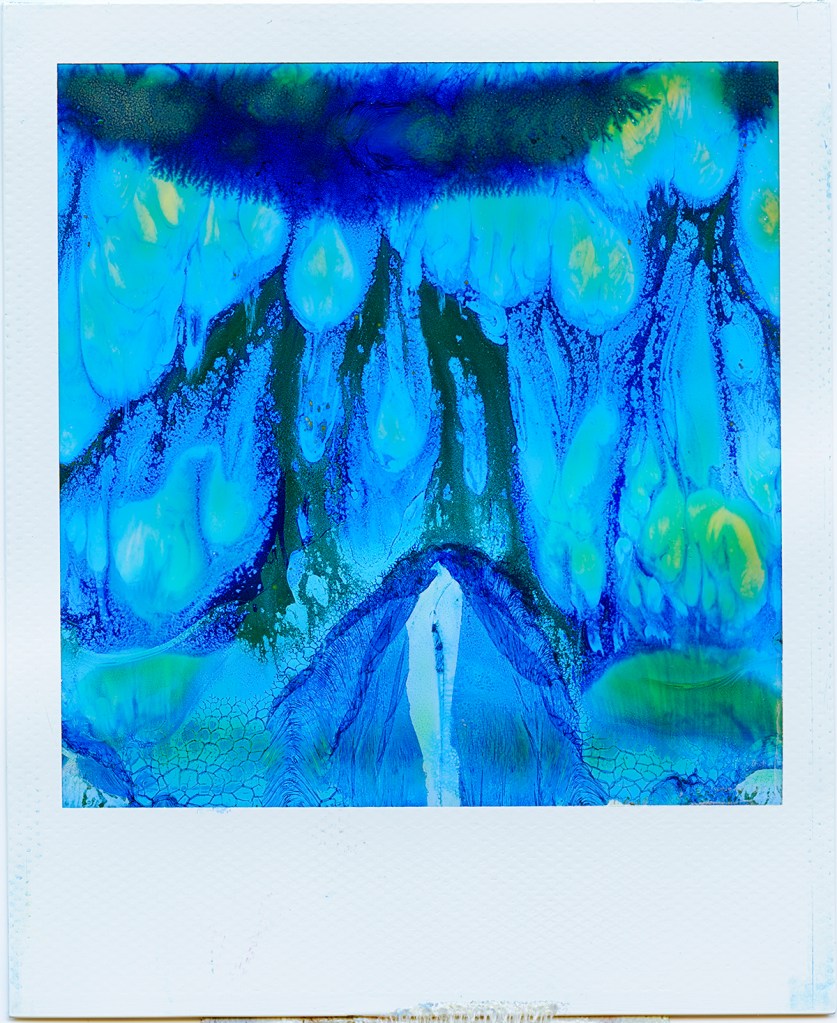

Mark Tamer: Yes, there is. Working with chemigrams (film chemicals mixed with various “resists’ on photographic paper in daylight) each attempt is different. The are way too many variables to get the same results, but that’s the appeal, being surprised by seeing something unexpected happen. Within all this chaos however, I can exert enough control so that some things are constant — the type of paper, or chemicals for example. It’s the same shooting with film. I use out-of-date film and cheap, plastic cameras so I never know quite how it will turn out but I can still use these materials to make a coherent series.

A little background:

My love of analogue processes and their inherent unpredictability came about a few years back when I was shooting only digital. I got to a point where I didn’t know why I was bothering to pick up a camera. It felt that any picture I made was just adding to an everlasting mountain of images used to feed the social media beast. Plus camera manufacturers were using processing algorithms that made all the photographs similar. Add this to digital’s capacity to correctly focus and expose every shot I was left wondering where were the mistakes, there were no surprises and therefore no magic.

I got to a point where I didn’t know why I was bothering to pick up a camera. It felt that any picture I made was just adding to an everlasting mountain of images used to feed the social media beast.

The moment that brought about the ending of digital for me was when I read about a photographic competition where one photographer had accused another photographer of plagiarism. They were sure the winning photograph of an iceberg off the coast of Chile had been stolen from them. It transpired that this wasn’t a copy, but that the accused photographer had stood beside the other photographer on a chartered boat, and had taken an identical shot at the same time. With camera algorithms being so similar, the two shots were identical. It felt we had gotten to a point where not only had we been everywhere in the world, we were coming back with identical images. So what was the point of me taking more of the same?

I love the idea of the experimentation involved with the chemigrams. Different types of paper, chemicals, methods. Is there an idea that you’re looking for something, trying to achieve a certain effect, or is the process of experimentation itself the important element?

Initially I start with just experimenting with different processes, playing with ideas that come to me (usually in the shower). Then I’ll combine a process with an idea and see where it goes. My most recent chemigrams are exploring a kind of nether world, something between up and down, dark and light etc. I need enough control so that all of the works stay within the theme, but other than that I let them do their own thing. I like to be surprised when I look at the finished piece.

I’m curious about this balance with the “images from a broken camera” as well, the balance between happy accident and calculated destruction. Did you break the camera? Do you look for broken cameras or have ways of breaking them yourself, in search of a certain effect or out of curiosity about what effect it might have? How does this balance play out in all of your work? The balance between breaking something and finding something broken.

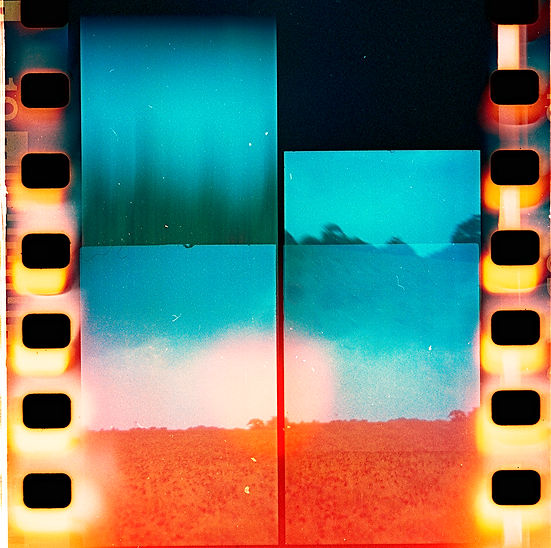

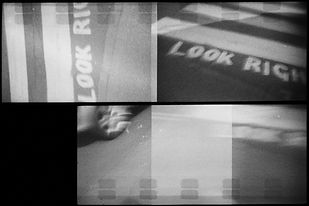

My “broken camera” happened accidentally. It’s a super cheap, plastic toy camera with four lenses that are meant to fire in a sequence – one, two, three, four. But since it broke it goes one, two, two-and-a-half, stop. Then when I wind it, it goes – three, four. I’ve always believed the medium shouldn’t be invisible, but out there for all to see. I don’t pretend the photograph is the thing itself, it’s a piece of paper, or an emulsion-coated piece of plastic. Working with analogue processes allows me to incorporate this into my work. So returning to your question, It’s okay to break something deliberately, or incorporate accidental breaks, but it should be employed as part of a thought-out process and not just used as an aesthetic.

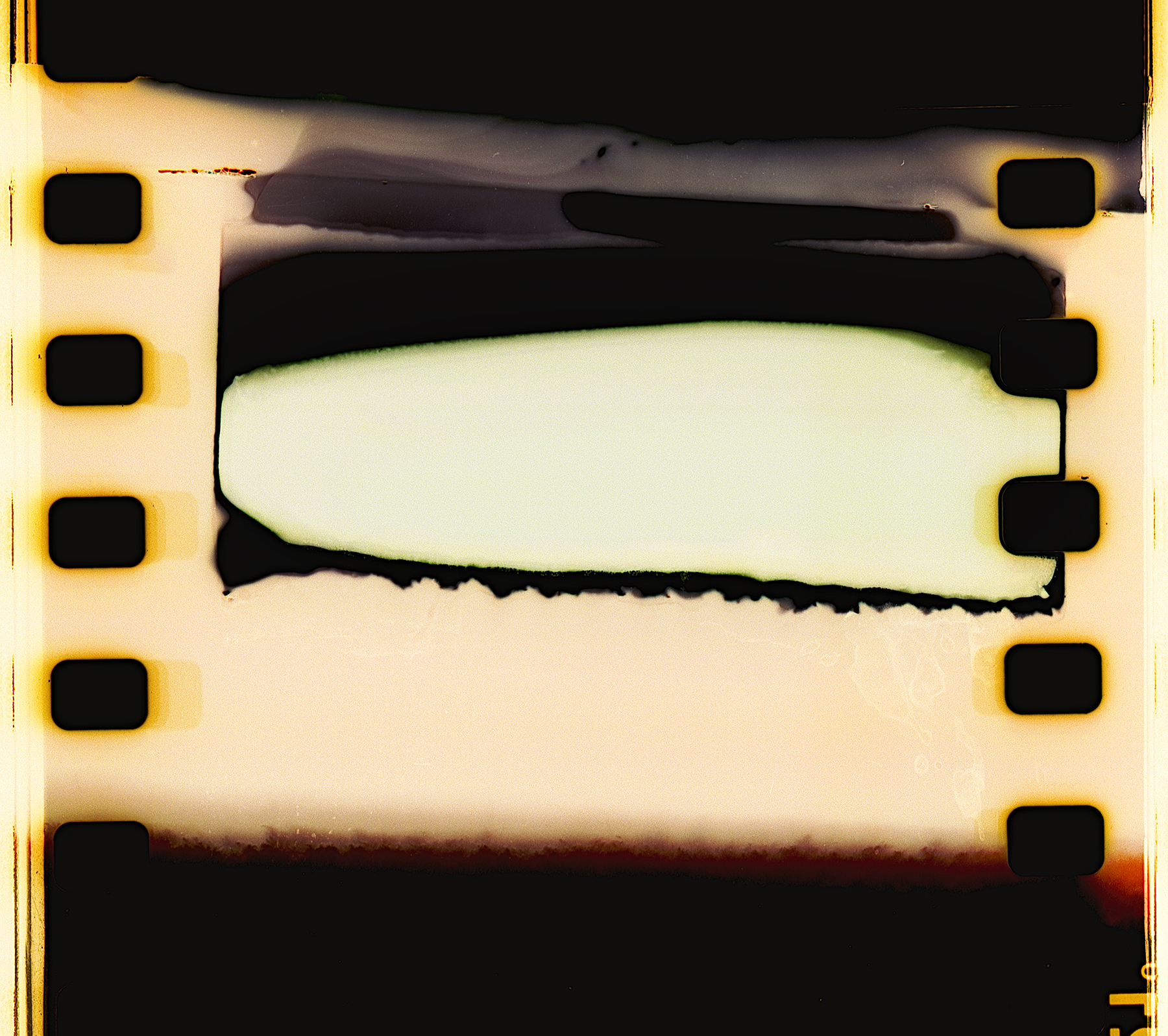

I love the “Everybody’s Happy Nowadays” series, which shows the lost images at the beginning and end of a roll of film. It’s another thing I miss from the analog days … this idea that there’s a limit, that there’s a start and an end to the possibilities, and that when you had a roll of film you had to think about what you’d shoot, and you’d just shoot till the film wouldn’t advance any more. (Now we can take a million pictures with our phones. We don’t have to decide or plan or think of a before or after.) The light itself in the images has a sort of ghostly longing feeling. Can you talk about the process involved with these images? Are they “found” or planned?

I agree with you about the finite possibilities of one roll of film as opposed to the “tyranny of choice” available with digital. I think the way we use and think about photography has shifted significantly recently. It used to be that a photograph referred to the past — I was here and I saw this. With phones however, and I see this more with the younger generation who grew up with this, it’s often more of a “I’m here now”, with the images shared in the same moment as they were taken. And then, quite often discarded.

It used to be that a photograph referred to the past — I was here and I saw this. With phones however … it’s often more of a “I’m here now”, with the images shared in the same moment as they were taken. And then, quite often discarded.

The Everybody’s Happy Nowadays series were all “found” on my films. I didn’t plan them in any way. That’s a big part of the appeal of using analogue film, yes it’s slow and expensive, but it does give you moments of magic. When Fuji, Canon etc. make available their cameras, they are designed to make perfect photographs. However, these blurry, light-leaked, abstract artefacts* can sometimes sneak through, in oblivious defiance to the camera’s original intention. Little moments of anarchy.

* I use that term as the dictionary definition: something arising from or associated with an earlier time especially when regarded as no longer appropriate, relevant, or important

I think part of the reason the light is so beautiful to me is that it’s seen as a flaw or a mistake – getting in the way of the subject or ruining the image. But instead it becomes the image, and there’s something poignant about that. Also something about the way it makes us work harder to “read” or make sense of the image. How do mistakes, flaws, technical glitches, find their way into your work?

If I wanted perfection I’d use digital — it’s easier, faster, more accurate etc. Digital is like Switzerland, all very nice and clean but pretty boring. For me, the interesting stuff happens when there’s a bit of chaos and unpredictability. I like to be surprised by what I make, so it’s a big part of the process. I’m often a little slap-dash with my method — mixing photographic chemicals in approximate rather than measured quantities, or just pointing the camera in the rough general direction and I also like to leave dust from the negative or chemical marks from the process on the image.

The camera and photographic process are designed to be invisible, so often a confusion arises. The thing in front of the camera and the photograph itself are conflated into one, when they are two very separate things. The photograph in front of you is really all there is. Including the maker’s marks and any “mistakes” on the image, helps remind us of this.

It’s interesting and somewhat sad to me that they’ve invented apps to mimic these imperfections and make our slick digital images and videos look older. Apps that mimic super-8 films, with scratches and camera flares, or IG filters meant to look like washed-out 70s film or daguerreotypes or images from other eras. It’s a sort of manufactured nostalgia that breeds sentimentality rather than emotion. How do you feel about advances in digital photography, and about apps and filters that alter the image in these ways?

Yes it’s boiling down analogue photography to a particular look or style that is added to your image. That’s a very surface-level thing. One of the reasons I use analogue is because the process is as important as the final image. With a one-click filter you’ve missed all that out. Also, I think it’s interesting that digital camera makers and the photography apps are making these filters available, it’s almost as if they instinctively know that digital is missing something.

At the same time, I like to think about movements like the French New Wave, when irreverent rebels took advantage of cheaper and lighter equipment to lay bare the conventions and means of production that had formed such a stodgy and stifling film industry. Do you see the potential for digital photography/phone photography and video, which is so much more accessible to everyone, to have this same revolutionary impact? Or is it too late?

Yes, well digital isn’t all bad! I use it every day just like most people. And I do think broadly speaking that digital has put the “means of production” into so many more hands than before. Plus the ability to share means we can see into the lives of people from everywhere and anywhere. So I think it has already been revolutionary.

Which brings us to your manifesto, (which reminds me of the passionate writing in the Cahiers du Cinema by filmmakers who felt a responsibility to shape the language of film) with your call to action for “… artists and photographers [to] remind us of both the illusion that photography creates and the magic upon which it is built. The challenge now is for artists and photographers to show us not only this world and how it affects our day-to-today life, but how it informs our understanding of all that we see.” I see in your photography a demand for the viewer to question how we read a photograph, and, in turn, what we notice in the world around us, by defying expectations, reframing the composition and the conversation. How do the ideas in your manifesto inform your own work?

I wrote the manifesto when I was asked to do an artist’s talk. I thought it would be an interesting way to approach it and also for me to get clear in my own mind why I do what I do. I also have a shorter personal manifesto that informs my work more directly. It includes statements such as “By engaging with the physical material in front of you, you are in the moment, only now exists.” Just to keep me on track. I like limitations (less choice) and so another statement reads, “All new projects must be named after a Buzzcocks song.”

One of the ways your work provokes questions is the sense of subject or focus. In Dislocation, for instance, we’re not looking at the buildings or the people but above them or beyond them, to things that are more fleeting, often on their way out of the frame – birds, clouds, planes. You find a space outside of the human realm, in a way, or a pocket in it. Or in many of the series we’re not looking at a traditional subject at all, but almost seeing the process itself. How do framing, point of view, angle, provoke us to read the world and our place in it in a different light? In general, with all of your work of different degrees of abstraction, how do you approach the notion of “subject” in your work?

Well I guess I have two approaches. One is the more abstract photography where it’s as much about the process as the result and then there’s the more traditional camera + subject. With the latter I’m still thinking about process but also there’s an undeniable thing in the photograph. However, it’s more about a mood or a feeling, than the thing itself. I’m trying for a more dream-like quality, that why my framing and angles are sometimes a bit “off.” In my Dis-location series the title is taken quite literally, I wanted the feel of an old movie that is slipping on and off the projector.

I’m trying for a more dream-like quality, that’s why my framing and angles are sometimes a bit “off.” In my Dis-location series the title is taken quite literally, I wanted the feel of an old movie that is slipping on and off the projector.

It sometimes seems to me that most good art, and certainly much photography, is about time passing. In the instance of photography in particular, it’s often seen as a way to freeze a moment in time, to capture it. In your manifesto you say, “Photographs don’t exist. They are like a scar we carry with us or like footsteps in the sand. They carry the trace of a past event but they themselves – the paper, the chemicals or the glowing pixels can only exist in the present – an ongoing now.” Some of your chemigrams, as I understand it, change or fade even as you create them. Can you talk about the notion of the passing of time, memory, anticipation, in your work and photography in general?

There are many “times” in photography. There’s the time the photograph is taken, the time it is developed or digitally finished and the time in which it is viewed by someone, all of these making connections through time. And with physical prints there’s the aging of the photograph itself. Becoming worn and faded by light.

When I create a chemigram there is a much longer moment of time, an extended now, a process that can last a few hours — kind of like a long exposure photograph capturing a longer period of time. When someone looks at that finished image they can escape the photographic sensation of “that happened then” as they can only see the thing in front of them. A piece of paper with some shapes and colours. I guess it’s an attempt at a zen-like state of paying attention to the now.

In Breakdown you talk about capturing an expression of energy, and somehow I misread the next bit to be “not unlike a ghost,” which made me think of those old photographs in which mystics and seers pretended they could photograph ectoplasm. But also, of course, of punk music, something vital and urgent, brutal and basic. How does your musical sensibility play its way out in your work?

Ha ha – the ghost in the machine. I think the line is “not unlike a guitarist using feedback…” but a ghost could work too. Actually, I have an old series of smoke images, distorted to look like ectoplasm!

To answer your question though, I think it’s the punk rawness and the no-bullshit approach I try and apply to my work. I love looking at art and listening to what others think about it too, but I do get a gut reaction to the arty-wank speak you often see. Don’t hide your work behind incomprehensible jargon, it’s alienating and elitist. Just be honest and let it speak for itself.

“I am an experimental photographer working with both analogue and digital mediums. Through my work I’m looking to find a balance between chance and control, and between; construction and destruction, signal and noise and ultimately, life and death. I embrace the accidents and errors as they not only remind us how vulnerable and delicate we are, they can often show us something new. It is at the point of breakdown that the medium begins to reveal itself. Through glitches and mistakes we get to see the base elements, the very construction of the material that creates those illusions of reality, the apparatus of photography itself.“

See more of Mark Tamer’s work on his website and on Instagram at unreelcity.

Categories: featured, featured photographer, interview, photography