By Jim Poe

This essay originally appeared on Jim Poe’s blog, Under the Paving Stones

“Those of you who follow my writing may have noticed it’s been a bit quiet around here for the last few months. There’s a specific reason for this: almost all of my extra attention and energy has been consumed by following and protesting the war and genocide in Gaza. I haven’t really been able to focus on much else (aside from having to keep it together as a parent). Early on I decided that writing about pop culture just wasn’t a priority during this crisis, so I decided to take a hiatus.

I haven’t even really felt like watching movies or reading or anything if it doesn’t have to do with Palestine. Everything feels weird while thousands of kids are being killed — Christmas feels weird, nice summer days feel weird. Things that used to comfort me seem empty. So much has changed in such a short time — decades happening in weeks. It feels like decades ago that I would think of sitting down to write about Mad Max or Barbie or a Susanna Hoffs novel.

Which sucks, because writing about pop culture has always brought me joy and kept me sane. But it’s like that poem by Marwan Markhoul: in order for me to write about Barbie, the warplanes must be silent.

I’ll get back on the horse and start doing this regularly again soon. I have some things planned, including a review of André 3000’s gorgeous ambient album, a tribute to Jenny Nicholson, and an essay about Bluey. I think when I do get back to it, more of my writing will reflect the new reality, because connecting pop culture to politics is just what I do. For example, I can’t stop thinking about the allusions to Palestinian resistance in Andor, and I think I need to do some writing about that.

But before any of that, I plan to focus more directly on Palestine and culture. That feels most appropriate right now, the best way to feel like myself while engaging with this crisis. I’m starting with this essay about Elia Suleiman’s marvellous Palestine trilogy of films.” – Jim Poe

I first saw Elia Suleiman’s The Time That Remains, the concluding film in his autobiographical Palestine trilogy, when I was working at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival in 2011. It was one of the standout films of my four years at that festival, where I gained a lifelong appreciation of Arab cinema; it really stayed with me and I thought of it often, even before October 7. It’s an important and worthwhile film for many reasons, but the most significant thing about it for me is that it taught me about the Nakba.

The Nakba, which means “catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the bloody ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948. Fifteen thousand people were murdered by Zionist paramilitary forces, and hundreds of thousands were driven out of their homes, becoming history’s largest refugee population at the time. It’s almost embarrassing to admit I’d made it to the age of 40 without much knowledge of the Nakba, but it’s not surprising either, given I was raised in the US as a Christian Zionist. The amount of ideology that Americans have to overcome before they start questioning things is mountainous.

I’d instinctively supported the Palestinian cause since I read about the First Intifada as a rebellious teenager in the late 80s, but I wasn’t really that educated about the history. It’s kind of amazing to consider how many more people would support a free Palestine if they could just know the truth about what happened in 1948.

The Time That Remains is like no other historical drama; it’s a very weird, very enigmatic, very funny film. But it’s unflinching about presenting the violence and injustice of the Nakba — which Suleiman’s parents survived, and indeed their story is at the core of the film’s narrative.

For that reason alone it was huge for me. How many other fiction films depict the Nakba? The only other one I know about is the 2021 Netflix feature Farha (which I haven’t seen). How many others made outside the region even mention it? Are there any at all?

Suleiman’s trilogy — Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996), Divine Intervention (2002), and The Time That Remains (2009) — are universally considered among the greatest Palestinian films and Arabic-language films ever made. What I love about this is how weird they are — I love it when films that defy convention are so widely embraced.

What I love about this is how weird they are — I love it when films that defy convention are so widely embraced.

Suleiman’s trilogy is so striking in the way it sets aside almost any notion of conventional storytelling. There are no other films like these, with their disjointed approach to autobiography; their dreamlike mood; and their wild mix of satire, comedy, and heartfelt meditation on history and oppression. It’s like Suleiman invented his own cinematic language to describe the the absurdity, the farce, and the tragedy of occupation.

Suleiman’s films are not only standouts in Palestinian cinema, but in international cinema as well; they’re worlds ahead of most festival and arthouse fare. I love this kind of weirdness; I don’t want predictable stories and I don’t want things explained to me. I’m tired of festival films that do the same things over and over: I’m tired of static shots and long silences, quirkiness in place of ideas, and minimalism mistaken for depth.

What’s interesting about Suleiman’s style is that he too employs silence and quirkiness — no doubt some of the lesser films I’m speaking of are influenced by him — but his films are so colorful and full of life and have so much more to show us than most of their ilk. Despite how inscrutable they are, occasionally taxing the viewer’s patience, at the same time they’re so funny and appealing and glowing with a warm humanism. For every scene that feels as impenetrable as an experimental short, there’s another one that’s laugh-out-loud funny or genuinely exciting.

Coupled with Suleiman’s wry, observational visual style, it’s as if Keaton had stepped into a Jim Jarmusch film.

As is often noted, silent comedy is an important stylistic reference point for Suleiman — E.S., the protagonist who represents Suleiman himself, and is for the most part played by Suleiman, never utters one word in the entire trilogy. With his wonderfully expressive face and fluid gestures and movements, Suleiman comes on like a modern Buster Keaton — the more so when he’s involved in slapstick capers like comically foiling the Israeli cops who storm into his home in Chronicle of a Disappearance, or pole-vaulting the apartheid wall in The Time That Remains. Coupled with Suleiman’s wry, observational visual style, it’s as if Keaton had stepped into a Jim Jarmusch film.

In this Guardian interview with Suleiman from 2002, the director said he’d never seen a Keaton film — nor had he seen any films by Jacques Tati, the other director he’s constantly compared to. “My films have a silent movie aspect only because I don’t know much about making films,” he admitted. “So there is a naivete and a literalness that’s similar to the comedies of the silent era.”

I find this both amazing and heartening. I love it when filmmakers arrive at their own style or voice without fawning devotion to the canon; I love that kind of rule-breaking naivety in a visionary filmmaker.

I find this both amazing and heartening. I love it when filmmakers arrive at their own style or voice without fawning devotion to the canon; I love that kind of rule-breaking naivety in a visionary filmmaker.

That said, I think it’s still relevant to bring up Keaton when discussing Suleiman’s work — whether we argue that Keaton’s primal influence filtered down through the other filmmakers who did directly shape his style (he names Jean-Luc Godard, Robert Bresson, and Yasujirū Ozu as his faves), or whether, as Suleiman indicates, it was some kind of cinematic convergent evolution.

But the references don’t all stem from arthouses and film school: Suleiman loves to mash up his styles, and some of my favorite scenes in the trilogy are the wonderful tributes to mainstream Hollywood action movies — such as the sublime bits in Divine Intervention depicting a lone, unnamed Palestinian woman (Manal Khader) as an avenging superhero, with explosions and special effects straight out of The Matrix.

Then again, when he sets aside the absurdism in the opening act of The Time That Remains in order to recount his parent’s experience of the Nakba, it’s as powerful and moving as any historical drama.

Watching the trilogy as the genocide in Gaza unfolded, I found myself wondering if some contemporary viewers might be disappointed by the overall lack of direct polemics about the injustice of the occupation, or surprised by the comical tone. Suleiman’s pranksterish approach might confound some. “What is Suleiman saying with this style of comedy?” asks the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw in his otherwise positive review of The Time That Remains. “It is difficult to tell … Tremendously well-turned though the film is, there were times when I wanted to reach into the screen and shake Suleiman and ask him what on earth he thinks about the situation.”

Suleiman’s absurd sensibility and detached style have led some critics to assume he’s rather aloof about the political turmoil and violence of the occupation — that he presents it as some kind of tragic “both sides” conflict, or that he eschews confrontation. In his review of Divine Intervention, the late Roger Ebert said, “Suleiman’s argument seems to be that the situation between Palestinians and Israelis has settled into a hopeless stalemate, in which everyday life incorporates elements of paranoia, resentment and craziness.” The Guardian’s Bradshaw describes his films as “a cultural and emotional resistance to the Israeli state: not rage, but a defiant buoyancy of spirit, a flower in the gun barrel of oppression.”

That Suleiman collaborated with many Israeli cast and crew in making the trilogy, including his line producer and close friend Avi Kleinberger, would seem to add credence to this interpretation. At times, Suleiman goes out of his way to humanize Israelis: The Time That Remains depicts Suleiman’s father Fuad rescuing an Israeli soldier from the wreckage of a burning vehicle. This could be interpreted as that kind of peace ’n’ love outlook that liberals (including liberal Zionists) cling to. The kicker comes in the next scene: both men lie side by side in the hospital but it’s the Israeli who gets priority attention from the nurse, while she closes the partition on Fuad.

It doesn’t surprise me that liberal critics, even ones I respect like Ebert and Bradshaw, would interpret the films this way — that “both sides” narrative about Palestine is a deeply entrenched trope in the liberal media. But I think they’re off the mark. I think it’s a mistake to miss the anger and resentment lurking beneath the comedy. Contrary to what Bradshaw writes I believe there’s definitely an underlying rage against the occupation in Suleiman’s work. It’s not always obvious amidst the surrealism and slapstick, but then it rises to the surface and you can’t mistake it. Take the amazing scene in Divine Intervention when E.S. drives along a country road eating an apricot, then casually flicks the pit out the window just as he drives by an IDF tank — and the impact of the pit causes the tank to explode in flames. It may be like something straight out of Monty Python, but I don’t know how you can interpret it any other way than as a howl of rage against the occupation.

In The Time That Remains, during the opening act that depicts the Nakba, there’s a scene in which a troop of Zionist militia pass by a Palestinian woman in a Nazareth town square. Some of them are in disguise as Palestinian fighters, wearing keffiyehs, making like they are escorting the rest as prisoners so that they can enter the town unmolested. The woman yells a greeting at them. “Victory is ours!” she cries. “They’ve been brought to their knees!” One of them responds by shooting her in cold blood, leaving her to bleed out and die in the street.

It happens fast — you would miss it if you turned away from the screen for a moment — but it’s significant because it’s the most raw and direct depiction of the genocidal violence against Palestinians in the entire trilogy. It’s a jarring contrast to the more dry and comical tone that dominates the proceedings (such as the later, cutesy scene in which Israeli cops try to shut down a club in Ramallah and end up rapping over the dance beat on their loudspeaker). I think Suleiman included it because he didn’t want the viewer to be lulled into forgetting about the reality of the occupation. It serves as an emotional anchor and gives us a clue as to the horror, outrage, and tragedy that animate the absurdism.

There’s no exaggeration whatsoever, either; from what I’ve read it was far, far worse. Reading about the Nakba will give you nightmares. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this scene reminds me of the summary execution of the old Jewish man by a Nazi officer in Schindler’s List.

In that 2002 Guardian interview, responding to a controversy in which something he said at Cannes was interpreted as opposing Palestinian statehood, Suleiman flatly states that he wants a free Palestine from the river to the sea, doing away with any notion that he sees it as a “both sides” thing:

“I want an end of occupation. That is what a Palestinian state should mean. I oppose the notion of statehood as it stands at the moment. And yes, I do think that Israel should cease to exist as a state for the Jewish people and commence to be a democratic, secular state for all its citizens, and that includes the one million or so Palestinians living there who are marginalised, with racist practices against them. What I want to see is this: no religion, multi-national, open borders.”

You can’t say it more clearly than that — and with the unprecedented mass movement for Palestine that has erupted around the world in the wake of October 7, more people than ever support that position. A free Palestine is a demand no longer relegated to the margins.

Chronicle of a Disappearance, the trilogy’s opener, is about Suleiman’s return to his home of Nazareth after years spent in exile in London and New York. That’s the logline anyway; the experience of watching it is far more disjointed than that suggests. It’s less a story and more a series of vignettes about life in Nazareth and Jerusalem with not much discernible structure. At times it feels like an observational documentary — Suleiman’s parents, Fuad and Nazira, play themselves, and among the locations is their real home in Nazareth. At other times it’s like a dream.

It tests the viewer from the opening scene, establishing an experimental feel with a close-up of Fuad sleeping in his recliner that goes on far longer than you expect. Listening to the sound of his breathing and watching the wrinkles on his face for several minutes creates an almost trancelike mood. This is followed by Suleiman’s aunt (Juliet Mazzawi) sitting in his parents’ living room and addressing the camera in an extended single shot, telling a hilariously bitchy and raunchy story about a family member and her dramas, before she and Nazira head off to a funeral.

Forgive me for such an obvious point — Suleiman hardly ever spells things out this directly — but this level of intimacy with an elderly Palestinian family in their home, in what amounts to documentary footage, is a political statement in and of itself. Palestinians are not only subject to racist dehumanization in the Western media, but they’re seen as a monolith — just a cluster of nameless foreigners who are defined only by anger or tragedy or grief (depending on how much compassion the viewer might have).

Suleiman’s dad looking like my grandpa or anybody’s grandpa taking a nap; his aunt’s rambling, salty story, sounding like anybody’s salty auntie: these are the human beings the Zionists don’t want you to know about. The simple fact of how few films have ever been produced by the tiny Palestinian film industry shows the significance of these human portraits — however abstractly Suleiman renders them.

As low-key as they are, these intimate moments will come to have significance by the time the trilogy is done and we know more about their stories. Fuad and Nazira both survived the Nakba. Their moments of peace, the small details of their lives, are framed by historic catastrophe, if not overshadowed by it.

But also their home looks nice in a midcentury working-class way, and it’s obvious they have hopes and dreams and tastes and perspectives that stand quite apart from the political situation. It’s awful to contemplate how historic injustice imposes itself on ordinary people who just want to live their lives. This tension is one of the main themes of the trilogy.

In the first half of Chronicle, titled “Nazareth Personal Diary,” the narrative and documentary modes intertwine. In some cases we’re not sure if what we’re seeing is observed or staged; I imagine it’s both in some cases. A fishing trip with several men on a boat doesn’t add to the narrative but it’s nice just to spend time with them — and one bit of dialogue between them gets one of the film’s biggest laughs. I get the feeling they might be Suleiman’s real mates and he asked to tag along and film them. The scenes featuring E.S. (in his leather vest and shades looking very much like a New York hipster who just got off the plane) hanging out with the proprietor (Jamal Daher) of a tacky gift shop in Nazareth are likewise chill and enjoyable even if there’s nothing going on. The Jarmusch influence here is very strong. In place of a plot, it feels like the film is something that’s happening to you; it’s very pleasant to be pulled into its meandering vibe.

Later, in The Time That Remains, we get the backstory about the gift shop: Jamal is Suleiman’s old friend in real life. Suleiman didn’t see him for years while he was in exile after fleeing Israeli security forces as a teen (I think this is the disappearance the title refers to). So there’s a real-life emotional resonance there that isn’t obvious at first, and that makes the hybrid-documentary mode especially valuable.

Other scenes in Chronicle involve an extreme detachment that’s sometimes comical, sometimes eerie, such as the running gag of two brothers getting into a physical altercation in the parking lot of the gift shop. These scenes, which, again, are not connected to anything else in the story, are shot from a distance (from a nearby rooftop) so that you can’t see the men’s faces or hear what they’re arguing about. Instead the viewer is meant to meditate on the absurdity of human conflict.

Meanwhile, E.S. is strangely decentered, wandering in and out of the proceedings like a ghost; if you didn’t know he was played by the director you wouldn’t even know the film is about his life story.

The early scene that foregrounds E.S.’s silence is so brilliant and laugh-out-loud funny: he’s introduced at a conference in Jerusalem, and the host tells the assembled audience that E.S. will talk about “his film’s subject, his narrative technique, and the cinematographic language he’ll be using.” But as he takes the podium and opens his mouth to speak, the mic emits squalling feedback. As a tech tries to fix it, the audience begins to lose interest, leading to disorder in the conference hall and the cancelling of the talk. There will be no speaking for E.S., here or anywhere in these films.

What’s the significance of this silence? Is it commentary on the real-life silencing of Palestinian voices? Or is it something more whimsical on the part of Suleiman, just an affectation that amused him so much he decided to run with it? My guess is a bit of both.

The commentary gets somewhat more direct during the second half of the film, “Jerusalem Political Diary,” even as everything gets wackier. The tone completely shifts from hybrid-doc to spoof as E.S. falls in with a mysterious woman, Adan (Ola Tabari), who seems at first to be a terrorist, but turns out to be more of an agit-prop prankster on a mission to sow as much confusion as possible in the Israeli authorities. In the climactic scenes, Adan uses a found police walkie-talkie to send the cops on a wild goose chase like something out of The Pink Panther or Airplane!, regaling the Israelis with a crass version of their own national anthem.

One of my favorite gags in the film is one of the silliest: sneaking around Adan’s underground lair, E.S. finds what seems to be a pistol; it turns out to be a cigarette lighter. Mel Brooks couldn’t have done it better.

This sense that the Israeli forces are clowns, and not the brutal oppressors they really are, recurs throughout the trilogy. I don’t think Suleiman means to make too much light of the situation; I think the levity is his way of poking holes in the ideology of the occupation, and depicting it for the fiasco that it really is beneath all the violence. That said, it was pretty weird watching these comedic shenanigans while a genocide unfolded. Things feel very different now.

“It’s not about getting people to learn about Palestine, because I think that they learn about Palestine when they laugh. They become a little bit Palestinian, just by that.”

In the 2002 Guardian interview, Suleiman explained the comedy in his films this way: “It’s not about getting people to learn about Palestine, because I think that they learn about Palestine when they laugh. They become a little bit Palestinian, just by that.”

Divine Intervention takes the political commentary and satire of the second half of Chronicle and develops it more fully. But, because Suleiman never does anything straightforwardly, before it does anything else it gives us one of the weirdest and funniest things I’ve ever seen onscreen: a man dressed as Santa Claus (George Ibrahim) being chased by a gang of youths in the countryside outside of Nazareth. After some bumbling slapstick, the youths catch up to Santa and stab him to death. It’s an unforgettable image in a film full of them.

For a filmmaker who calls himself “naive,” Suleiman is so assured and dare I say masterful here with his mix of comedy, satire, documentary, politics, and surrealism. Take the amazing early scene in which a man methodically lines up empty glass bottles on his rooftop in Nazareth, just so he can hurl them in a fit of rage at the police when they arrive. Again, it’s shot with that extreme detachment; we watch him from a distance, bringing the bottles from downstairs a few at a time with obsessive persistence.

The seething anger and frustration beneath the comedy is an important theme. In many ways the entire trilogy is about anger, and futility. At the start of the film, E.S.’s father (this time played by an actor, Nayef Fahoun Daher) waves at everyone he sees as he drives along in Nazareth while cursing under his breath at them (“What an asshole … What a cuckold … Fuck your sister-in-law … Fuck your mother’s sister”). Two neighbors engage in a bitter little war of throwing their garbage into each other’s yards. The same man who threw the bottles at the cops recounts an acerbic tale about his brother beating up someone who was blocking his driveway.

This is the human condition; people can be this petty everywhere you go. But also these are the kind of resentments and frustrations that fester when your homeland has been taken away from you.

While Divine Intervention doesn’t have anything resembling a conventional story, two roughly sketched narratives thread the satire. In one, E.S.’s father is hospitalized with a heart attack. From what I’ve read in interviews this is at least loosely based on real life.

The other narrative is a completely silent romance between E.S. and the unnamed woman played by Manal Khader. E.S. lives in Jerusalem and the woman lives on the West Bank, in Ramallah; so in order to carry on their affair they must meet at a checkpoint. Their furtive meetings in E.S.’s car, caressing each other’s hands in silence while they watch the Israeli soldiers bully and harass others passing through the checkpoint, are a sensual, funny, and poignant satire of the dystopian barriers that divide Palestinians from each other.

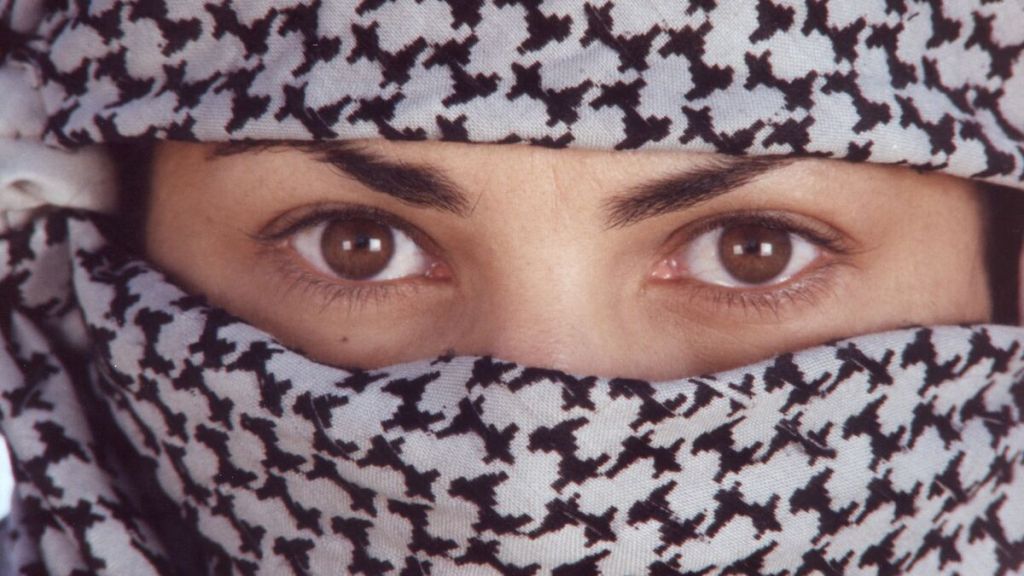

The woman is also the subject of some of the most thrilling and memorable scenes in the entire trilogy. In a series of setpieces that both satirize and pay tribute to Hollywood action movies, the woman becomes a symbolic figure of Palestinian resistance, expressed in a persona resembling a superhero. In one scene, she strides nonchalantly right through a checkpoint, stylish in her dress, heels, and shades; while Israeli soldiers gape at her helplessly. Whether through telekenetic superpowers, or perhaps the divine intervention referenced in the title, the guard tower collapses, and the soldiers scramble away as she walks on unperturbed in slow motion — a sly reference to the “walking away from explosion” Hollywood trope.

I also love the track that’s playing during this scene: “Joi” by Fingers. It’s a soaring progressive-house breakbeat anthem with Sufi-influenced vocals by British singer Susheela Raman. I love that Suleiman incorporates so much electronic music throughout the trilogy.

Even better is the dreamlike climactic scene in which the woman confronts a group of Israeli cops who attempt to shoot and kill her, only for her to reveal herself to be some kind of invincible being. This scene is even more overtly influenced by The Matrix, X-Men and other blockbusters of the era. I find that so delightful: one of my favorite things in life is when arthouse films borrow from genre pictures (and vice versa).

Here, Suleiman employs imagery of Palestinian resistance and recontextualizes it like it’s a comic book. The woman’s kheffiyeh becomes a whiplike weapon, which she uses on her foes like Indiana Jones. Then she has a Captain America moment with a bulletproof shield in the shape of Palestine.

At one point, floating in the air, she stops the bullets aimed at her as if she was Magneto, and they circle her head like a golden crown or a halo — so that the scene suddenly takes on religious (divine) symbolism.

The whole scene is so cheeky and offbeat — the choreography of the cops as they approach her, guns drawn but making moves like they’re in an MTV video, is high comedy, balancing out the popcorn-movie excitement. At the same time it’s so politically adamant: when she dispatches all her enemies the ground transforms triumphantly into a Palestinian flag. It’s without a doubt the greatest fictional depiction of Palestinian resistance I’ve ever seen onscreen. Why shouldn’t real-life resistance get the Hollywood fantasy treatment? It’s awesome and so inspiring.

But perhaps the film’s most iconic scene is the one in which E.S. releases a balloon with Yasser Arafat’s face on it, and the balloon floats over the checkpoint and away towards Jerusalem, causing pandemonium amongst the soldiers. Along the way it flies over a number of Palestinian icons including the Dome of the Rock. The balloon obviously represents Palestinian freedom — floating over barriers, going wherever it will, untouched by the frustrated occupation forces — expressed in the most buoyant, childlike, whimsical way. The reference to the classic children’s film The Red Balloon makes it that much more delightful.

The music laid over this scene cracks me up: it’s composer Marc Collin’s loungey main theme from French heist flick Les kidnappeurs, which became a late-90s Café Del Mar chillout standard. The juxtaposition of the childlike balloon, Arafat’s smiling face, the ancient monuments of the Old City, and the sleazy lounge electronica with its John Barry and Ennio Morricone influences is just sublime.

After all the quirkiness and abstraction of the first two films, the first act of the The Time That Remains, detailing Suleiman’s family history during the events of 1948, finds the director operating in a mode that’s as close as he comes to convention.

And the thing is, that’s refreshing. This may sound weird but it reminds me of when Sonic Youth, who were so brilliant at noise and experimentation, started applying themselves to writing songs with more structure and broad appeal. Those songs kicked ass. The noise informed the structure, if that makes sense, and made it more thrilling.

This part of the film is as riveting and powerful as any historical epic by Spielberg, Coppola, or Scorsese — in some ways more so, because the story of the Nakba had never been told on the big screen like this.

Fuad is now played by the iconic Saleh Bakri, who’s starred in many other great Palestinian films including Annemarie Jacir’s classics When I Saw You and Wajib (the latter is one of my favorite films of this century; I wrote about it a couple of years ago for Australian national broadcaster SBS).

The opening act follows the young Fuad as he desperately attempts to organize resistance to the Haganah, the Zionist militia encroaching on Nazareth. The young Nazira is depicted here too (played by Samar Oudha Tanus). In a lovely and moving scene, Fuad receives a letter from her telling him that she’s fled with her family to Jordan; and pleading with him to lay down his arms to save his life, and to keep her in his heart. Moments later he sees them driving away, Nazira staring at him longingly out the window of the car.

Fuad is a gunsmith, and thus both a crucial figure in the resistance and a prime target of the Zionists. As Nazareth is being overrun and Fuad goes into hiding, he bravely risks his life to save a fellow fighter who’s been shot. The result is that he’s captured and taken prisoner, a fate that could symbolically represent that of all his people.

Despite the more straightforward approach in the first act, Suleiman’s sense of the absurd is still in effect, only now it’s employed with more purpose than ever. A scene in which the Haganah loot a house is played with a certain amount of comedy, as the soldiers handle the furniture with exaggerated delicacy while a stolen phonograph blares.

In this 2009 Guardian interview, Suleiman says he improvised this scene based on testimony from an elderly Nazareth woman whose home they filmed in. “She showed me bullet holes in her house. She had brought stuff from Beirut on her honeymoon, and then the Haganah arrived and started to take it. I said, ‘I’m gonna take revenge for you.’”

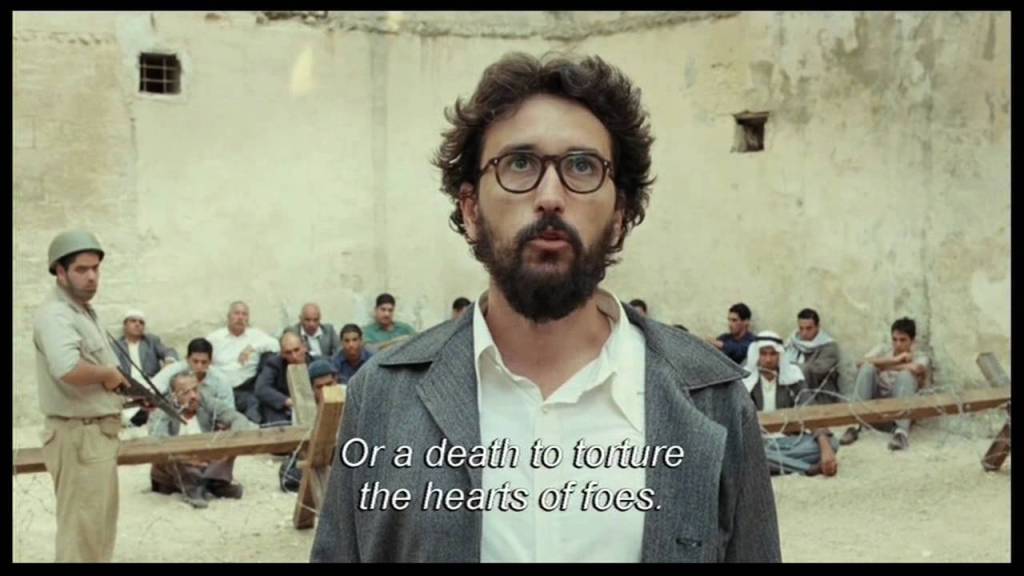

In a wrenching scene, a poet who has been taken prisoner (Alex Bakri) reads his captors an indictment of the catastrophe before abruptly shooting himself: “I want no life if we’re not respected on our land.”

In that Guardian interview, Suleiman says he urged his father to tell the story of his experiences during the Nakba after he became sick. It’s obvious from the results onscreen that Suleiman takes a great deal of pride in his dad’s role in the armed resistance. Fuad is presented as a reluctant hero who never willingly gave up fighting for his country even in the face of defeat. In contrast to Fuad’s courage and resolve is a farcical scene in which the mayor of Nazareth and local religious leaders capitulate all too easily to the invaders.

Bakri’s performance is outstanding, with his mixture of determination, apprehension and, in the long years after the Nakba, fatigue and resignation. In these later scenes, set in the 1960s and 70s during Suleiman’s boyhood, the middle-aged Fuad is a withdrawn man prone to silence and rumination; he also suffers from poor health. He and his family still live in their home in Nazareth, having avoided the fate of the hundreds of thousands of refugees. Though they are poor, it seems like a nice home and their life doesn’t look terrible. Even so the emotional and psychological devastation of being colonized takes its emotional toll, on the young family and everyone they know. Nazira writes letters to family in Jordan that she knows she’ll never see again. There’s a running gag in which a neighbor regularly threatens to immolate himself in the street, obliging a weary, cynical Fuad to intervene and prevent the suicide each time.

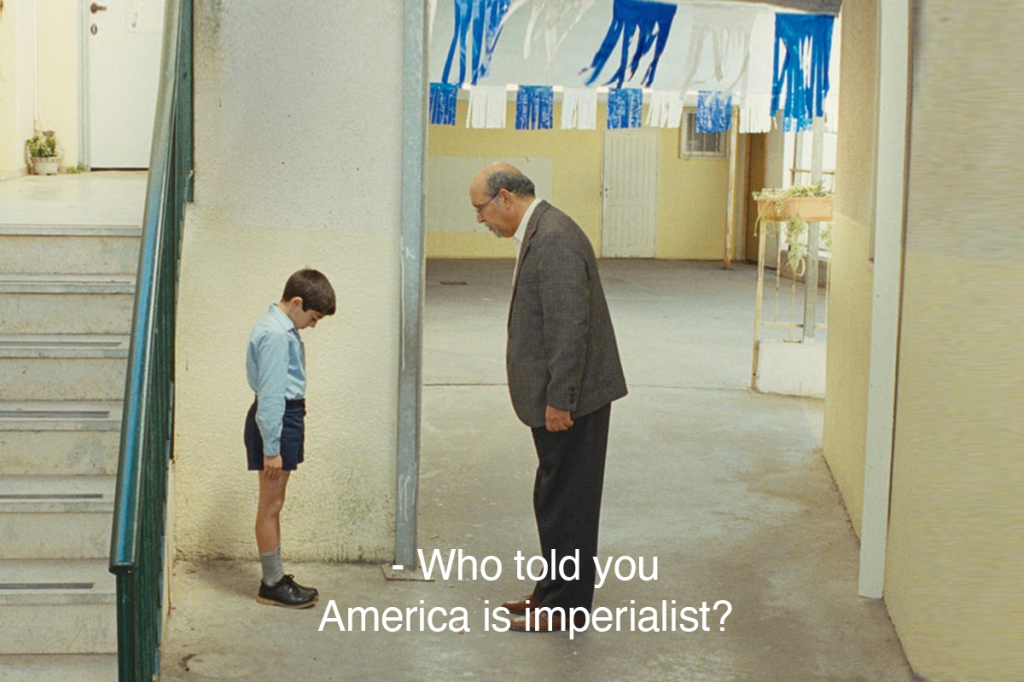

The absurdity of the occupation is shown most poignantly when the young E.S. (played by Zidane Awad) attends an Israeli-run school in Nazareth. A group of Palestinian girls are made to sing the Israeli national anthem at an event for a visiting dignitary; their rote, wooden performance contrasted with the garish display of Israeli flags is both funny and terribly sad.

But the indoctrination doesn’t work on E.S.; he repeatedly gets in trouble for political subversion. “Who told you America is imperialist?” asks the principal. It’s never answered onscreen, but we know it was his dad.

There’s a hilarious bit in which the schoolchildren watch Spartacus in class, and a teacher desperately attempts to block the screen during a steamy love scene between Kirk Douglas and Jean Simmons. It’s wonderful to ponder the childhood influence of this great classic of leftist cinema about a Roman slave revolt on Suleiman’s filmmaking and politics.

(If you’re ever at a cinema trivia night and the question is, “What does The Time That Remains have in common with Clueless?,” now you know the answer: they both interpolate Spartacus.)

Fuad’s escape is fishing on the ocean — but even here he finds no peace. Another running gag (there are lots of them — repetition is key to Suleiman’s style) involves Fuad and a friend being interrupted by Israeli soldiers every night they go out fishing, again and again, and asked who they are and whether they have their ID cards. The tone is friendly enough (“Any fish?”), but the implication is clear: this is no longer their land and they don’t really belong here. Given that the sea is one of the terms in the famous and controversial protest slogan, this is a quietly poignant bit.

The Time That Remains is a gorgeous film: cinematographer Marc-André Batigne suffuses both the historic and contemporary scenes with Mediterranean sunlight and bright, cheery pastels. These sunlit pastels are everywhere you look: in the home interiors with their charming midcentury decorating, and in the Nazareth exteriors, with their pleasant gardens and cozy streets. It’s such a soothing, refreshing contrast with the muddy brown visual approach of many other modern historical dramas. There’s a wholesome sense of warmth and abundance, which contrasts with the anger, frustration and violence depicted in the story.

It occurs to me that this beauty and sense of abundance is not only a cinematic choice but a political one too. The idea that Palestine was a desert, a wasteland, a terra nullius before it was colonized; and the idea that in modern times it’s a mismanaged ghetto that would collapse without Israeli settlement and control, are important components of Zionist ideology. The early scenes of The Time That Remains show us a beautiful and rich land where people had nice homes and gardens and lives to live — before it was invaded and stolen from them.

In a very deliberate bit of symbolism, a group of captive fighters are detained by the Hagenah in an olive grove (olive trees are a symbol of Palestinians’ belonging to the land).

The film also de-Orientalizes Palestine; as depicted here, Palestine before the Nakba has more in common with Italy or Greece or other places in the Mediterranean region than it doesn’t. The kitchens and gardens look like those you would find in any warm climate anywhere.

In fact, the scenes set in 1940s Nazareth reminded me quite a bit of those set in Sicily in the same era in The Godfather. Later we realize this influence is overt when a comedic bit involves a character whistling Nino Rota’s famous Godfather theme.

Things come full circle in the final act when Suleiman recreates the homecoming that he documented in Chronicle. I’ll be honest: these scenes played better the first time I saw the film than they did more recently after watching the rest of the trilogy. The sense of aimlessness, with E.S. hanging out at the gift shop yet again, and his baleful eyes staring silently at the camera as he haunts his childhood home, are certainly imbued with emotion (Suleiman hugging Jamal after years apart is lovely), but they felt ever so slightly self-indulgent compared to the more forthright approach in the historic sections of the film. I found myself wishing it could have continued in that vein.

I’ve spent most of this essay defending Suleiman’s quirky, unconventional approach in this trilogy, but I feel it falters slightly towards the end. To continue my ridiculous Sonic Youth analogy, it reverts to noise when it could have used a bit more of that structure.

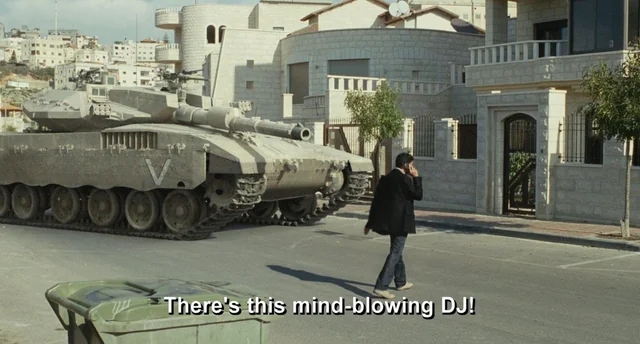

Suleiman is at his best in these late passages when he gets away from cruising in self-referential mode and instead combines his inspired visual humor with incisive political points. Perhaps the most famous shot in the film is the one in which a man is tracked by the gun of an IDF tank as he walks back and forth on a street in Ramallah, engrossed in a conversation on his mobile (“There’s this mindblowing DJ!”) and ignoring the tank. Suleiman has said this is also based on a true story: a man in Ramallah told him that this really happened to him during the Second Intifada. Suleiman cast him on the spot to recreate it onscreen (though he added the phone call as “a bit of burlesque”).

There’s also a wonderful bit with the emergency staff at a hospital vying with IDF soldiers over an injured militant on a gurney. One group runs with the gurney in one direction, only for the soldiers to run him back in the other direction, presumably to keep him under arrest, and this keeps going back and forth, over and over. It’s shot from a distance, looking into the window of the corridor like it’s a fish tank. It’s uproarious and silly enough to be, again, worthy of Mel Brooks; but of course it’s also an indictment of the dehumanization that Palestinians face, even in injury and death.

So, I said what I said about the second half of the film, but don’t get me wrong: the final scenes of The Time That Remains are very poignant in depicting Nazira’s declining health and her son’s gentle and loving (but of course always silent) interactions with her.

I gather Nazira passed away before the film was made because this time in her old age she’s played by an actor (Shafika Bajjali), and a title card at the end dedicates it to her and Fuad. This is the meaning of the film’s title, I believe: Suleiman’s efforts to find time what time he could with his parents in their last years after his return from exile.

It hits me that time must be different for an occupied people. Like all their generation, Nazira and Fuad saw the invasion of their country when they were young, before spending decades living with the disastrous consequences. Then they died without seeing its liberation. That’s a bitter and absurd thing that no one should have to go through in their life.

It’s to Suleiman’s credit as an artist that he was able to take this bitterness and craft a series of films filled with so much comedy, love, beauty, adventure, humanism, and political insight, along with the anger and frustration. I don’t think it’s right to say he transcended the anger — that would be a liberal cop-out. Instead I’d say he put the anger to use and made something transcendent. He managed to tell not only his own life story, but also, in his own skewed, oddball, meandering way, that of his beloved parents — and all of it framed in such a way that it tells something about the story of a nation fighting for its liberation.

“My name is Jim, and I‘m a writer, DJ, presenter and activist based in Sydney. I’m originally from the U.S.; I was raised in Oregon, graduated from high school in Georgia, attended the University of Southern California, and then lived in New York City for most of my adult life before moving to Sydney in 200. I studied cinema/TV at USC. I’ve worked as a club DJ, an organic farm worker, a produce manager, a freelance writer & journalist and a film publications editor, among many other things. My resume is checkered to say the least.

My writing on film, music and politics has been published by the Guardian, SBS Australia, Jacobin Magazine, Junkee, and Overland Literary Journal, to name a few, along with a bunch of websites that have since been taken down. I host Classic Album Sundays Sydney, a monthly all-vinyl hi-fi listening party.

I’m a passionate music fan and record collector. When I play out I usually play house, techno and disco; but I’m also way into indie, postpunk, electronica and ambient, country, soul, reggae, quality pop, and so much more. Though I’m 50 I usually prefer new music to old; I’m young at heart and suspicious of nostalgia.

I studied film production, and I enjoy making the odd experimental short, but I always had more of a feel for film theory and criticism. My tastes in film are what I would call “highbrow/lowbrow.” I love social realism, slow and experimental cinema; and I love genre pictures — fantasy, sci-fi, horror and action. I love Jafar Panahi and Kelly Reichardt as much as I love Star Wars and kung-fu flicks and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

I’m a dad and a househusband. Parenting is central to my life and also informs my politics, shaping my views on social reproduction and feminism. I haven’t written about parenting very much but I plan to do so at some point soon.

I was diagnosed with autism two years ago. It’s been immensely rewarding, but also challenging and a bit scary, to come to terms with that in middle age — to find out (late, but better than never) that there’s an explanation for why everything always seemed so hard, why I’ve never fit in anywhere in this society, and why I’m such an obsessive weirdo. The politics of neurodiversity and disability have become very important to me very suddenly. Again, I haven’t written about it much, but you can expect that I will.

As I said, I’m a socialist, and more specifically I’m a Marxist, and my politics are of a revolutionary nature. I may or may not write at length about Marxism here, but Marxism informs everything for me.

As you can see I have a lot of seemingly divergent interests, and you may wonder how they all come together. I don’t know how to explain it myself. Why is it that I might review Black Widow one week, My Bloody Valentine the next, and a graphic novel about Rosa Luxemburg the next? All I can say is the connections become more clear to me at lucid moments, like when I read about how important art was to the Paris Commune; or when it hits me how much the history of house music was shaped by the Stonewall uprising; or when I remember that George Lucas based his fictional Rebellion on the Viet Cong.

Also, I don’t know how to be anything but myself (that’s an autistic trait as I’ve discovered!), and these are the things that made me.” – Jim Poe

See more of Jim’s writing where this essay originally appeared, on his blog called Under the Paving Stones