By Alice Courtright

This past fall, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented an enormous exhibition on the life and legacy of Alvin Ailey, who lived from 1931 to 1989. Ailey, an extraordinary creative, dancer, and choreographer, was celebrated for his impact on modern dance, the boundary-breaking opportunities he gave black artists, and his commitment to creating innovative, delightful, and truth-telling dances, like Cry, Pas de Duke, and Survivors.

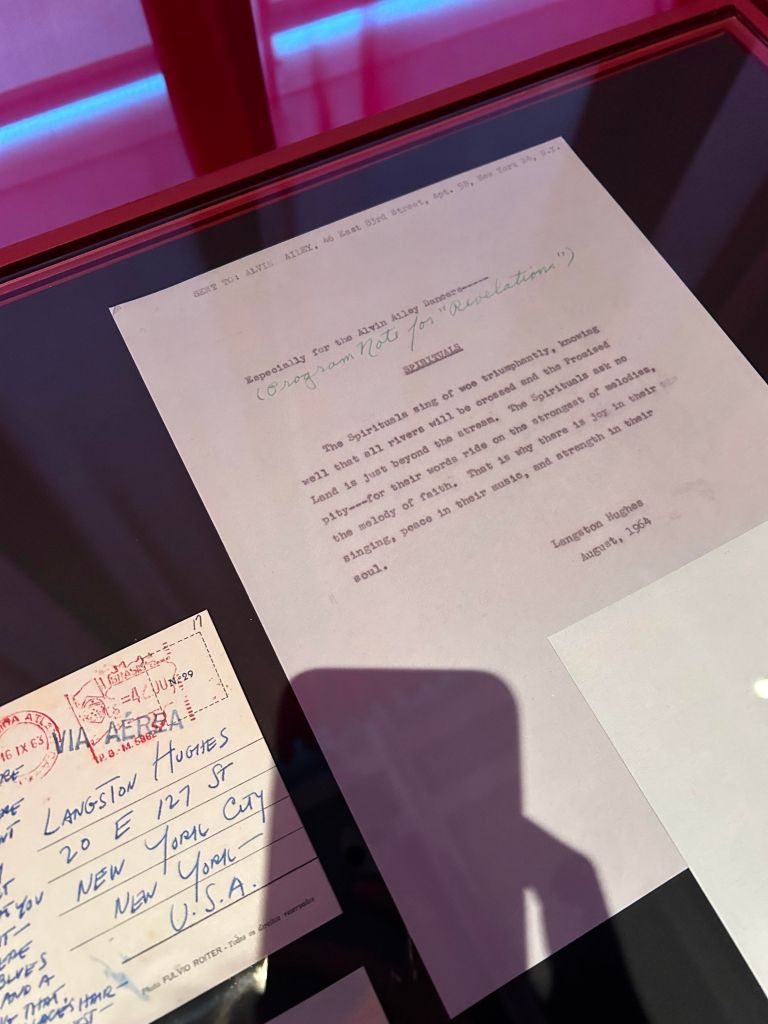

In a back wing of the exhibit, there were long glass display cases filled with Ailey’s notebooks and letters. Ailey had a wide circle of collaborators and influences, including Judith Jamison, Nelson Mandela, Hart Crane, Katherine Dunham, and James Agee. Postcards and journal pages revealed the breadth of his correspondence and reading.

One striking document was from Langston Hughes, designated “Especially for the Alvin Ailey Dancers” on the topic of spirituals, dated August, 1964. The Black Church, which was a major element of Ailey’s southern childhood, featured prominently in his dances. Hughes’ letter, written on a typewriter, was a program note for Revelations, which premiered in 1960. Hughes wrote, “The Spirituals sing of woe triumphantly, knowing well that all rivers will be crossed and the Promised Land is just beyond the stream. The Spirituals ask no pity — for their words ride on the strongest of melodies, the melody of faith. That is why there is joy in their singing, peace in their music, and strength in their soul.”

Revelations opens with nine dancers center stage, dressed in loose clothing and looking to heaven. They stretch their hands up to the sky and move in and out of a close formation as the spiritual “I’ve Been ‘Buked” plays. The dance is mournful, and the movements are serious and confident — they ask for no pity. There are no backlights, no distracting stage design. The dancers’ faces are set with strength and grace and their bodies move as witnesses to the lines of the old song: “Children, there is trouble in this world.”

In the spirituals, singing of woe triumphantly reflected both the brutal realities of slavery and the sustaining promises that pointed boldly toward a future of freedom and dignity and joy. As Frederick Douglass wrote in his autobiography, “Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” But there was more at work moving along the prayerful lines of the spirituals: there was an insistence on change. Douglass said, “A keen observer might have detected in our repeated singing of ‘O Canaan, sweet Canaan, I am bound for the land of Canaan,’ something more than a hope of reaching heaven. We meant to reach the North, and the North was our Canaan.”

In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, Ailey interpreted the spirituals for the challenges of his own time, and for the hopes he had for himself, his country, and the world. His dances are beloved not only as pillars of the modern dance movement, but because, in line with the spirituals, they are witnesses to a man who reimagined the intractable problems of his time through art with both honesty and hope.

Today, the voices singing of and documenting woe, whether it be sociological, environmental, or political, are rarely, as Hughes puts it, triumphant. Visions of a future are crushed under the horrors of the present. The contemporary theologian Willie James Jennings understands why: “Such an invitation to life together may seem ridiculous in face of the brutal operations of statecraft, where threat and counter-threat are the shared currency of nations and groups.” But, he pivots, “What we need now, however, is a different calculus of the imagination. Configuring a space of hope has real-world consequences.”

The 20th-century German philosopher, Edith Stein, wrote extensively on the relationship between the impossible challenges of the current moment and the contrasting possibilities hidden in the infinite. She wrote, “Hope puts the memory into emptiness since it occupies it with something that one does not possess.” But emptiness for Stein, who was murdered in Auschwitz in the Second World War, was not a kind of sentimental forgetfulness. Rather, emptiness is a form of “dryness” that humbles the soul with honesty and a growing sense of personal limitation and corruption. This purgative dryness, writes Clement Harrold, can be equated with a kind of “dark night of the senses… into which the soul freely enters in order to be freed from all disordered attachment to the things of this world.” The result of Stein’s emptiness bears the fruit of new angles of inquiry, a reimagining of problems and crises that seem stuck in paralysis or cycles of violence.

In our age of environmental collapse, socio-political polarization, and brutal warfare, the jazz composer Andromeda Turre has created a new album that pulls the listener into “a dark night of the senses” and configures a space of hope. In From the Earth, Turre, who is the daughter of jazz legends Akua Dixon and Steve Turre, offers the listener compelling tales of ecological hardship — borne by humans and nature alike — and a glimpse of a different kind of reality, one hoped for but not yet seen.

“Artists like Billie Holiday, Max Roach, Gil Scott Heron, and Nina Simone have preserved the practice of jazz as oral history — an afro-diasporic tradition that traces its lineage back to the Griots of West Africa, through the work songs of the enslaved, spirituals, blues and jazz.”

In a recent interview, Turre said, “Jazz is a music steeped in tradition. Artists like Billie Holiday, Max Roach, Gil Scott Heron, and Nina Simone have preserved the practice of jazz as oral history — an afro-diasporic tradition that traces its lineage back to the Griots of West Africa, through the work songs of the enslaved, spirituals, blues and jazz. Each generation of jazz has artists that have reflected the struggles and hopes of their time, a legacy I hold dear and carry forward through my own creative practice.”

From the Earth is composed of four jazz concertos that each reflect a different realm of planetary life: the geosphere, cryosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere. The album begins with otherworldly sounds and chimes, and the prophetic call (voiced by poet Betty Neals) to listen to the heart, “the unifying axis of the spheres,” which acts as a connecting guide through the four concertos. Neals invites the listener to “put aside the place where dreams lie rotted. Let the laughter live a little.” The album, from the first, is an invitation to receive, listen, imagine differently, and prepare to be left “worn out, but satisfied.” From the Earth isn’t a panoply of wishful thinking, but points toward what John Lewis called in Carry On a “more peaceful society,” one that must come about from the inner transformation of each citizen.

“Despite everything that we see with our eyes, what are we feeling and imagining for the future of humanity and the future of Earth? I’m envisioning and embodying a call home to nature, where we are connected, and where humanity understands and remembers that we are nature, and that we’re a part of the earth. We don’t live on it, we live with it. And so, the hope of that dream of mine is what I tried to weave through From the Earth.”

Turre described her intentions for the album to me: “Despite everything that we see with our eyes, what are we feeling and imagining for the future of humanity and the future of Earth? I’m envisioning and embodying a call home to nature,” she said, “where we are connected, and where humanity understands and remembers that we are nature, and that we’re a part of the earth. We don’t live on it, we live with it. And so, the hope of that dream of mine is what I tried to weave through From the Earth.”

In her ballad, “Hydrosphere,” Turre sings, “It’s time to start a new day. It’s time to come alive.”

From the Earth is fully grounded in moral and political thinking, where there is united civic and ecological healing. The songs testify to the complex realities of ecological hardship, especially how the burden of environmental devastation is borne most heavily by disenfranchised communities of color. In Turre’s song, “Ms. Margaret’s Lament,” she sings, “Walk a mile in another’s shoes, you’ll be singing out the blues.”

Activist Ms. Margaret Gordon describes the smog in West Oakland, California, and the truck lines that move through residential neighborhoods due to zoning laws, sometimes ten thousand trucks in a day. The trucks emit so much pollution that windows cannot be opened and are covered with a film. Turre belts, “What if we all had to stay in the bed we lay, in the mess we made? We’d figure a way.”

Ms. Margaret, the co-founder of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, describes the crisis of asthma over the smooth drums and bells, “You know that one out of five children in Oakland to the flatlands goes to the emergency hospital from the ages of 0-5… Fifty percent of the children have inhalers. Before they go out to play at recess they have to use inhalers. And then when they come back in.”

Turre conceived of the album on a trip to Iceland, where she was standing inside a glacier. She wondered, “How can I get more of humanity to feel this connection to the earth?” Turre, who trained as a vocalist at the Boston Conservatory and Berklee College of Music, dancer at the Ailey School, pianist, activist, and composer, opened her skills toward these mysterious and transcendent questions. For as Charles Marsh said for the Project on Lived Theology, “Hope and miracle and mystery animate the protest against cruelty, focus moral energies, and heighten discernment of those places in the world that cry out for our healing and wholeness.”

From the Earth is full of reverence for human and ecological intelligence, which animates the protest on behalf the suffering planet and its living creatures. On one moving track, “Cryosphere,” Turre sings for the melting ice. An iceberg laments its falling cliffs. Turre sings the haunting lines,

I’ve seen the others fall

And always felt invincible

But now, it’s happening to me.

Will you remember me?

My cliffs and all their glory.

This feels so incomplete

A consequential story.

The grief and honesty of From the Earth are bound up with rhythms and stories of hope and joy. In “Sin Agua No Hay Vida” [Without Water There’s No Life], there’s the buoyancy of Latin jazz and the words of Dr. Gladys M. Canals, an environmental educator in Puerto Rico. In the song “Grandmother’s Permission,” Dr. Jifunza Wright-Carter, co-founder of the Black Oaks Center in Illinois, speaks about the harmony of soil microorganisms, where resources are not vied for but shared. Turre sings behind Dr. Wright-Carter’s voice, inspired by Abbey Lincoln’s moving, wordless vocals in “Tryptic: Prayer, Protest, Peace,” which Lincoln created with Max Roach (on drums) in response to the apartheid laws in South Africa. One wild song, “Amulena,” came to Turre in a dream, in which she was running with a herd of caribou. Inspired by Meredith Monk, who often sings without lyrics, Turre included on the track the glossolalia transcribed from the dream. There’s a sense of mysterious victory at play in Turre’s songs of climate lament, a trust and joy in a coming future that we must imagine and realize together.

From the Earth concludes with the anthem, “Critical Mass.” Turre sings her lyrics with a chorus of intergenerational voices behind her. “We have this moment, we have been chosen to hear this song and sing along.” The invitation echoes across the ages. Out of a deep tradition of triumphant woe comes a new voice, singing us into the future, inviting us to join in the song.

About the author: I was born in New York City in 1988. I studied English literature at Yale University and theology in Sewanee, Tennessee. I served as a school chaplain and teacher before devoting myself to family life. My husband, Drew, is a parish priest, and we have three daughters, who are my joy. We live in Hong Kong, where I love to learn about the arts, the natural world, and the movements of grace. When I can, I read and write about these things. See more of Courtright’s work at alicecourtright.com.

This is a fine post, evocative and compelling. You speak the truth which is no small thing. Thank you.

LikeLike