By Craig Hammill

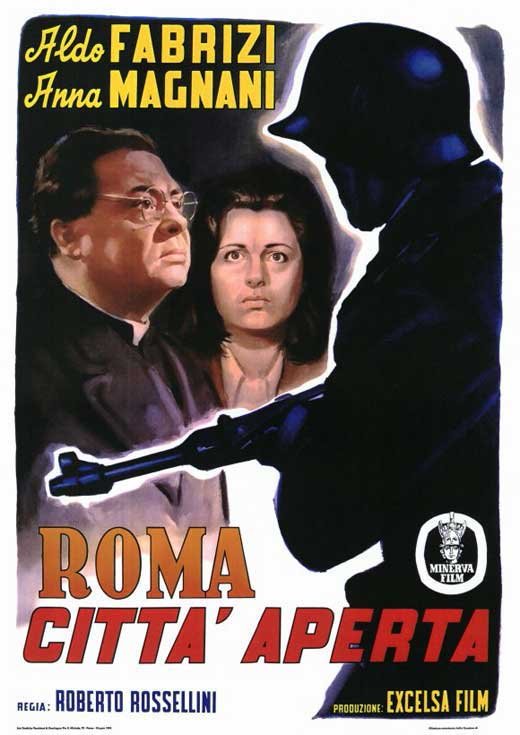

Rome, Open City

(1945, co-written & directed by Roberto Rossellini, co-written by Federico Fellini, Italy)

The most startling part of watching Roberto Rosselini’s Rome, Open City about the famed Eternal City under the World War II Nazi occupation is that it has lost NONE of its power.

A masterwork of the Italian neo-realist post-World War II genre, Rome, Open City tells the story of resistance fighter Giorgio and his attempts to evade capture by the Nazis. Giorgi’s life intersects with that of his friend Francisco, who is about to marry a vibrant good-hearted widow, Pina, and Don Pietro, the Catholic priest who will marry Francisco and Pina the next day.

Like so many great works, the movie takes place across a condensed very powerful few days. The unity of time and place lights up the movie with the violent vitality of Greek tragedy. Paradoxically, the very grim subject matter (and it only gets grimmer as the movie goes on) is also a stubborn celebration of what’s great in all of us.

Sometimes the idea of watching an Italian neorealist movie can be more daunting than the actual experience of watching it. Almost every time this writer has finally committed to screening another must-see movie and braces himself, he is stunned at how cathartic the Cinema is. This is kind of stupid considering that Italian neorealism has inspired the likes of Federico Fellini, Martin Scorsese, Elia Kazan. The genre paved the way for a revolution in filmmaking and acting style that transitioned much of world cinema from a kind of studio-bound classic style to a much grittier, on-location, truthful approach.

American film noir, the Kazan-directed masterpieces of the 1950s like Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, the nascent wunderkind works by TV-trained auteurs like Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayevsky, even a much later cycle of movies like the Lars Von Trier-led Dogme 95 movement all share a kind of DNA with Italian neorealism.

An angry, furious unvarnished look at the unfairness, violence, and tragedy suffered by everyday Italians during the Nazi occupation, the movie is one hundred and five minutes of difficult truth.

The genre is noted for tackling real-life stories without flinching away from the irreducible complexities of human behavior that war and poverty bring out. Many of these classics from Visconti’s groundbreaking 1943 Ossesione to De Sica’s 1948 Bicycle Thieves were shot on real locations with a mix of actors and non-actors, often giving the movies a hybrid fiction-documentary feel. Also, the extreme lack of filmic resources (no money for dollies, cranes, lights) caused Italian neorealist moviemakers to embrace the lack of tools to create a rough, anything to get the shot style that infused the movies with real-life force and vitality.

Rome, Open City, all that acknowledged, is in a class all its own. An angry, furious unvarnished look at the unfairness, violence, and tragedy suffered by everyday Italians during the Nazi occupation, the movie is one hundred and five minutes of difficult truth.

If you’ve never seen it or heard about it … good! You will be stunned by how strong the storytelling and writing are at the same time — you can never fully predict where the narrative is going to go (always the hallmark of the very best writing).

Co-written by a very young Federico Fellini, Rome, Open City is a mix of humanism, spirituality, earthy realism, and even sudden bouts of humor. A mid-movie sequence finds our resistance hero priest Don Pietro (played pitch-perfectly by Italian great Aldo Fabrizi) knocking out an old man with a frying pan to keep him from talking when Nazis walk into his apartment. But shortly after this much-needed moment of levity, a main character gets shot and killed shockingly. The alternation of devastating violence and quiet moments of connection and transcendence forms a kind of verse-chorus-verse structure that will thread the movie to its very last scene.

And while the movie is an angry movie (in the best possible way), it is also a movie about forgiveness and non-judgment.

Rome, Open City is also blunt, straightforward, and honest with its characters. We meet Showgirls with exploitable opium addictions who sell out boyfriends who don’t love them. Pregnant street-smart widows with juvenile delinquent children who still believe in God at the same time they work to help the underground resistance. There’s even a shocking moment late in the movie when a drunk German commanding officer laughs at an SS Nazi for believing in Hitler’s fascist Aryan master race. The drunk German (rightly) points out that all Nazis have proven is that the Fascists know how to kill and cause entire nations to rebel and fill up with hate.

And while the movie is an angry movie (in the best possible way), it is also a movie about forgiveness and non-judgment. This writer was surprised at how much of the movie, especially the second half, which has hard-to-watch scenes of torture, is about both fighting AND forgiving those you are fighting against. The movie is a powerful illustration of a certain strain of Christianity that views fighting for justice and liberty through real acts as key virtues.

The movie even has a two-part structure that might surprise folks. The first half takes place mostly in and around a Roman apartment building. The second part takes place mostly in the holding cells, torture rooms, and offices of an SS Nazi building. The structure is powerful, dynamic, strong, and surprising.

And finally, as with so much great cinema, the movie’s real glue AND life force are the actors and performances that imbue every scene with almost unbearable life force and emotion. The great Italian actor Anna Magnani, powerful, strong, sensual, earthy, fierce, plays the world-wise and weary widow Pina about to get married to the accepting Francisco. Aldo Fabrizi, a towering figure of post-World War II Italian cinema, plays the resistance-aiding priest Don Pietro with an understated yet powerfully grounded sense of composure and reserve. Their two performances (along with the amazing work of the entire ensemble) ensure that every scene is powerful and memorable.

Movies like Rome, Open City are lightning in a bottle. There’s a reason Rossellini’s masterpiece is considered one of the great works of world cinema. Many respectable, honorable works strive to capture history, human nature, a moment in our recent past or present. Only very few somehow make you feel YOU ARE THERE in the confusion, the dread, the fear, the somber determination, the good and bad moment-to-moment decisions.

While common wisdom often says it’s hard to tell a story with the needed detachment and perspective too close to when the events actually happened, sometimes that closeness catalyzes an immediacy and urgency impossible to recreate further from the big bang explosive moment of the event itself.

Rome, Open City, made just 1-2 years after the events it was based on, has managed to be both eternal and immediate. It is a bold and brutal beatitude. The horror of existence at whose center is nevertheless a sublime beating heart.

Paisan

(1946, co-written & directed by Roberto Rossellini, co-written by Federico Fellini, Italy)

Paisan continues the bold and shocking rhythms of Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. That is to say, the movie is at turns humanist, observant, romantic, serene, funny, brutal, violent, unbearable. Like Jean Renoir in France, Rossellini is a gambler of tone. He seems to understand intrinsically, as Renoir did, that life is NOT one genre. One emotion. One “vibe.” It is instead a horrific sublime cacophony.

Again co-written by a young Federico Fellini, Paisan is a natural progression, sequel to Rome, Open City. Where the first movie dealt with the German occupation of Rome during World War II, Paisan tells the story, in six connected but discrete episodes, of Italy’s liberation by the Allied forces in 1944.

The movie has the narrative progression of the liberation itself. The first story starts in the south on the island of Sicily, where American forces first landed to move northward. And each successive episode takes place slightly more north than the one before. The movie charts the progression of the Allies pushing back the German line/front. By the sixth episode, we are in Italy’s northernmost regions BUT we have crossed behind enemy lines where the Germans, in late 1944, still controlled territory. So there is a progression and escalation of danger and violence, and open combat as well.

The term Paisan refers to the Italian freedom fighters who were anti-fascist and fought the Germans alongside the Allies. Like the French freedom fighters, or really any resistance fighters in any occupied country, Paisans made bold choices with dire consequences. Anyone they came in contact with would be in immediate danger for aiding the subversives against the occupying force.

Fellini, interestingly, had issues writing about the Paisans for this very reason. And yet, he is the co-writer on two of the most powerful Italian movies about the Paisans. It was also here on Paisan that Fellini got a chance to start directing. Rossellini entrusted the young Federico with certain B-roll scenes. One senses the young Fellini’s humorous, humanist touch possibly providing a balance to Rossellini’s own drive for honesty, truth, brutal humanity. Yet Fellini himself adopted this Rossellini-esque strategy of being brutally honest AND openly loving. Both Rome, Open City and Paisan are brutal, shocking, violent movies. But they are also warm movies, a hallmark of Fellini’s great works. And the combination of brutality and emotional warmth is a shockingly effective cocktail indeed.

The six episodes ALL work. Unlike some anthology or episodic movies, the episodes have a uniformity in quality, focus, theme. While you might prefer or remember some over others, there’s not a bad or even mediocre episode in the entire movie (though a few flirt with melodrama).

And the combination of brutality and emotional warmth is a shockingly effective cocktail indeed.

The episodes progress also on themes of love, relationships, understanding amid war until the shocking final episode which we’ll get to in just a moment.

Before that harsh climax, we see American GIs haltingly trying to talk to local Sicilian girls; an African American MP realizing just how poor a young street thief is; an Italian call girl meeting an American soldier who knew her before she resorted to prostitution; a British nurse daring a trip to war-torn Florence to find a former love turned Paisan; a Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic trio of Chaplins spending the night in a monastery with Catholic Franciscan monks (who also turn out to be anti-Semitic and anti-Protestant). This penultimate episode is also the movie’s most quietly comical and it ends on a strange ironic note of both grace and gridlock. Of irresolution.

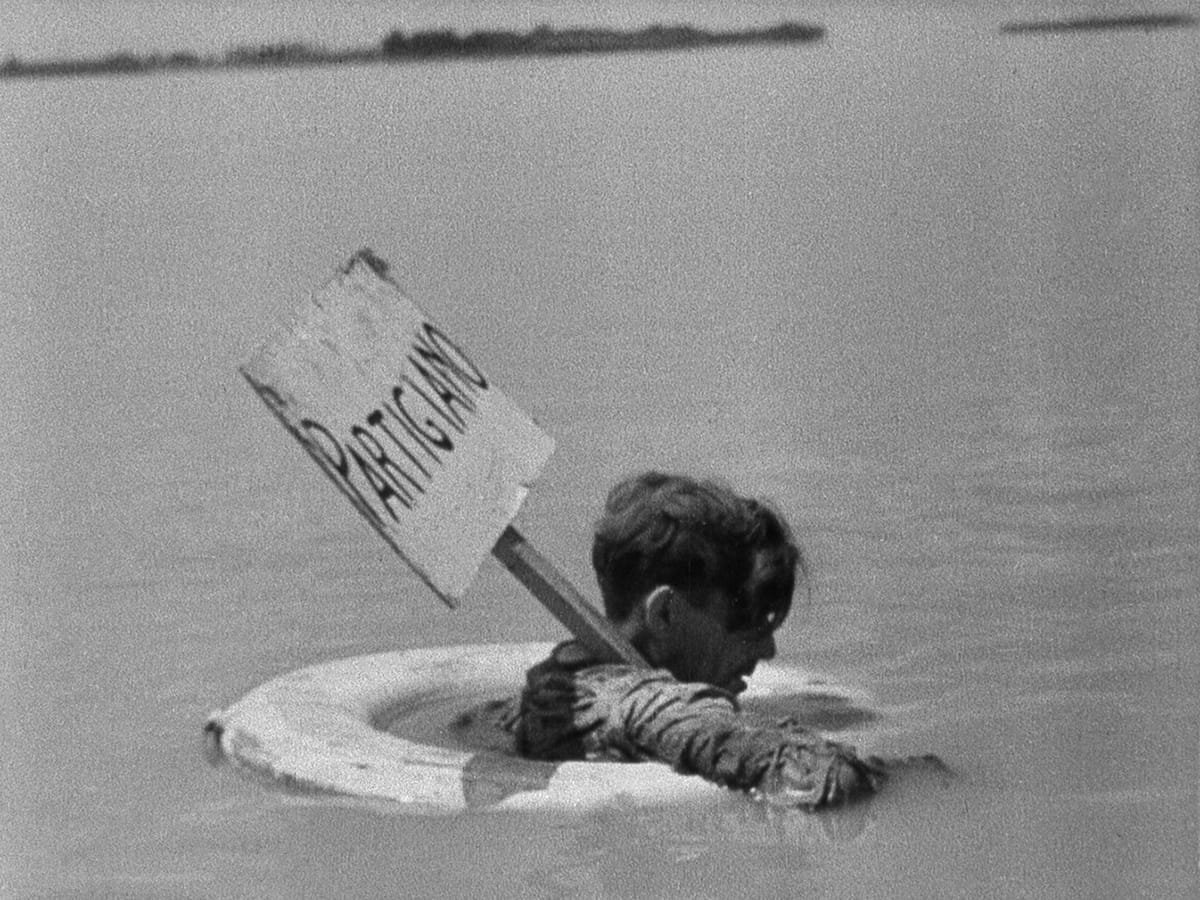

And then … we get the final episode which opens on a famous shot of a dead Paisan floating in the Po river with a sign calling him out as a Paisan. In the eyes of the Germans, a traitor.

This final story is NOT cynical. But it is unbearably brutal. We follow Paisans and American OSS (the precursor to our CIA) surrounded by Germans. When locals help the Paisans and Americans with food, they are repaid by being executed by German soldiers for assisting the enemy. This results in an unbearable image of a toddler wailing amongst the bodies of his slain mother and father.

And the very end of this episode, which we won’t spoil here, has a very rough scene that may have been an inspiration for an equally brutal section of Martin Scorsese’s Silence. But what this final episode drives home is that Paisans WERE NOT even afforded the basic rights given captured soldiers by the Geneva convention. Captured soldiers who, under international law, had to be kept alive as POWs. The Paisans were simply viewed as “outlaws” and treated little better than rabid dogs.

For the Italians, fighting for the liberation of their own country, IN their own country, there often was no reward, no liberation, no grace. In fact, the fight came with humiliation, degradation, and trauma.

And so the movie ends on a deep irony. That for the Italians, fighting for the liberation of their own country, IN their own country, there often was no reward, no liberation, no grace. In fact, the fight came with humiliation, degradation, and trauma.

Rossellini is quoted as saying that his commitment in these movies and some of his later works was to truth as best as he could film it. This in some ways might be his definition of Italian neorealism, the genre he helped define.

This commitment makes these movies stand out. Both Rome, Open City and Paisan are still shocking in their unflinching portrayal of the suffering, death, injustice, horror, compromises of war. Paisan also finds a way to comment meaningfully on things like racism, anti-semitism, poverty, survival, hypocrisy, spirituality.

There is a kind of cinematic essence in the best of the humanist moviemakers. Renoir, Ford, Fassbinder, Kurosawa, Fellini, Rossellini, Mike Leigh, Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao Hsien, among others, at their best, achieve a kind of pure cinema through the depth of their understanding of human nature. Though all these moviemakers are skilled movie craftspeople, it is their psychological insight that elevates their work to the ranks of the very best.

Paisan is occasionally melodramatic but it is not sentimental. It is a movie about the horrors of war and the occasional grace notes of triumph that still ring out. Made so close to the actual events themselves (Paisan was made just one year after the war ended), the movie has an immediacy and truth that feels like it could only have come from people who had JUST lived the experience they are now recreating. Who still had the fresh wounds and memories of exactly HOW IT WAS. This too might be at the heart of Italian neorealism. These masterpieces, made in the 1940s and early 1950s, are about experiences being lived daily by those who made the movies.

Rossellni never looks away. He never flinches. But he never misses an opportunity to celebrate what’s good in humanity either.

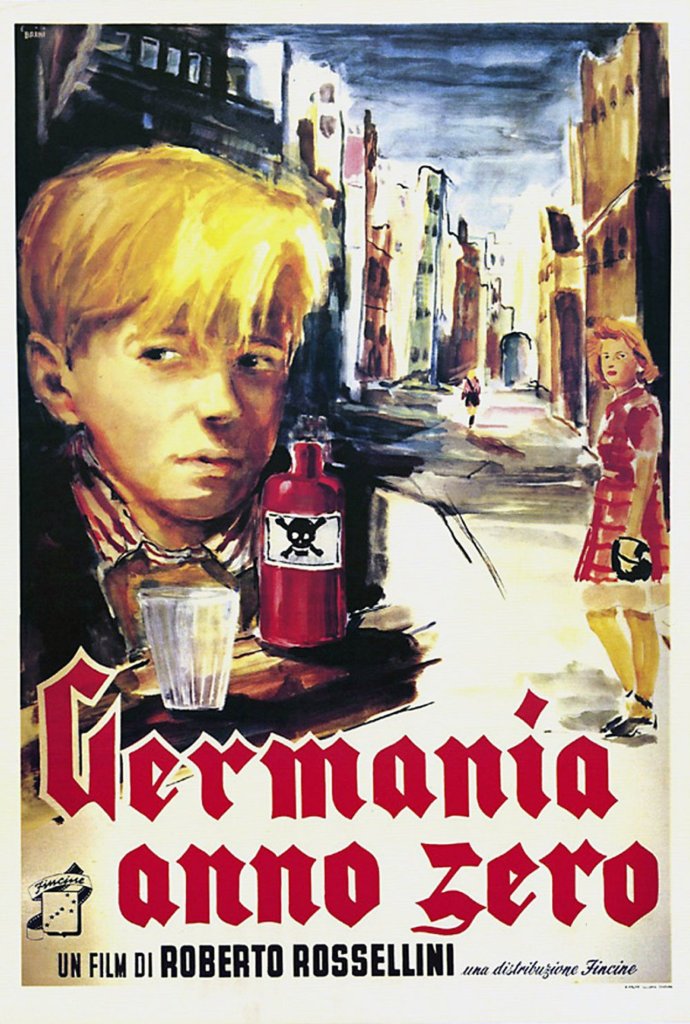

Germany Year Zero

(1948, written and directed by Roberto Rossellini, France/West Germany/Italy)

It should not be a shock that Germany Year Zero is the most brutal Rossellini movie of his War World II trilogy.

Despite having watched a woman gunned down in the street, a man tortured to death, and a priest executed in Rome, Open City, despite having seen two budding lovers killed and then entire families executed in Paisan, the experience of watching the brutal, unsentimental Germany Year Zero still grabs you.

Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero follows a young German boy, Edmund, as he wanders a bombed-out post-World War II Berlin, trying to find ways to help his struggling family. As so many similar families struggle in the immediate aftermath of the war. Edmund’s father is sick and ailing in bed. His older brother, Karl-Heinz, a German soldier, hides from the police and refuses to help the family for fear of being arrested. His sister Eva flirts with the boundaries of being a call girl, escort, girlfriend to get money, cigarettes, resources for the family.

The movie continues Rossellini’s commitment to showing things movies were not supposed to show. The five or six families who all share the same apartment are mean and petty to each other. Edmund encounters a former school teacher who is clearly a pedophile who procures young teenage boys for another pedophile. Edmund’s friends, if you can call them that, include a barely adolescent girl who seems okay trading sex for the meanest of attentions from other street boys.

You know this will be a rough ride when the opening scene is of Germans digging graves for money who chase away Edmund because they see him as competition.

Germany Year Zero goes beyond being brutal and ends up despairing. But how could it be anything else? These experiences and scenes almost certainly did happen in the immediate post-war aftermath.

The movie is a masterpiece.

Rossellini had just lost a son, Romano, to appendicitis. He dedicates the movie to his memory. And in interviews, Rossellini stated that he cast teenage circus acrobat Edmund Moeschke as young Edmund because of his similar appearance to his own son. Now what does that mean? It’s hard to even parse out. Why would you make such a bleak movie with the lead acting as a kind of surrogate for your just deceased son and then put that surrogate narratively through unspeakable horrors?

The movie almost feels like a proto Lars Von Trier movie a la The Idiots or Dancer in the Dark in that our lead goes through ever-increasing miseries yet feels almost angelic.

As hard as the movie is to bear, it becomes even more unbearable in its final twenty minutes. Edmund makes a misguided gut-wrenching choice with dire consequences. We won’t spoil it here as, in many ways, it is what the movie is all about. But it’s such a shocking decision that you wrestle with it.

Here, in Germany Year Zero, Rossellini almost seems to be trying to make a movie as an act of forgiveness.

It’s also clear once you watch all three movies in the trilogy that Rossellini, like a lot of Europeans, has a lot of fury at the Germans. Here, in Germany Year Zero, Rossellini almost seems to be trying to make a movie as an act of forgiveness. He knows the regular Germans are suffering as much as anyone. He shows it. The director has compassion … real love for Edmund, Eva, Karl-Heinz, and their father. Rossellini observes the daily struggles of the Germans and sees the iniquity in it.

And still, we get several characters, like the Nazi pedophile school teacher, who echo similar portrayals of Nazis in Rossellini’s Rome, Open City. That is to say, portrayals so one-dimensionally evil they border on being caricatures.

But when the entire world has had to suffer at the hands of a destructive, elitist, psychotic ethos can you blame the injured for not being magnanimous?

The power of the movie, and it is a powerful movie, lies in its central truth. How can you expect children to function in the world when all the adults around them have been weak, petty, or psychotic?

The power of the movie, and it is a powerful movie, lies in its central truth. How can you expect children to function in the world when all the adults around them have been weak, petty, or psychotic?

Edmund never has a real chance because the people he holds the most dear have let him down. His father has a clear-eyed view of what’s going on but his physical sickness mirrors his decades-long moral weakness. The father says “We had a chance to stop them (the Nazis) and we did nothing.” Edmund’s brother bought into the Nazi lie and fought as a German soldier. Now he hides in cowardice. Edmund’s teacher, who Edmund naturally would be inclined to trust, is a terrified ex-nazi who still finds time to paw sexually at children. And in fact, it is something this teacher says that causes Edmund to make a horrible decision.

Edmund wanders a bombed-out, rubble-strewn apocalyptic Berlin landscape. It just as well could serve as a metaphor for his inner state.

There is a rigor and anger to Germany Year Zero that feels like Italian neorealism as sharpened razor. As a vise we have to put our head in. The movie reminds you — oh yeah, this is what movies can be when the moviemakers have the craft, anger, work ethic, and genius to put all the elements into the imperfect furnace of movie creation and somehow use the pressure to create a diamond.

Late in the movie, in the depths of existential terror, Edmund stumbles upon a church organist playing a hymn in a bombed-out cathedral. Other passers-by, suffering their own traumas, all stop and listen. It is an amazing moment. And then everyone moves on.

Now at the end of the World War II neorealist trilogy, it is clear why these movies inspire so many. Even almost eighty years later, there is something naked, intense, daring about these works. Of course, they would inspire a Scorsese, a Kazan, an Ingmar Bergman. Movies up until that time had mostly still bought into the notion that movies should entertain. If they were daring or topical, they would still find a way to stumble into a happy ending or provide enough theatrical artifice to make the suffering depicted palatable. A dose of sugar to make the medicine go down.

There are no doses of sugar in these movies. There are moments of grace. Which also happen in real life. But those moments co-exist with horror.

Craig Hammill is the founder/programmer of Secret Movie Club. This article first appeared there. See more on facebook and Instagram.