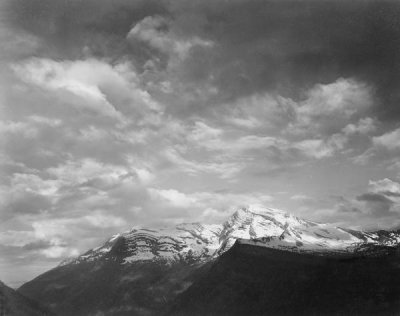

One day last week was, supposedly, the coldest day in years, and we even had a fairly substantial amount of snow. I like a cold spell in winter. It feels cleansing. The summer after a mild winter always feels extra swampy and teeming. And extreme cold feels surreal and other-worldly. It feels alive. It feels like another reminder that the world and everything in it is so much vaster than our human understanding and so far beyond our control. Though, of course, our actions affect it all.

These cold spells always remind me of Faulkner’s strange and beautiful Wild Palms, in which a couple, Charlotte and Harry, strive to escape conventional morality and propriety. “They had used respectability on me and … it was harder to bear than money. So I am vulnerable in neither money nor respectability now and so They will have to find something else to force us to conform to the pattern of human life, which has now evolved to do without love — to conform, or die.” The story starts in Chicago, and it’s plenty cold there. The city in winter “herds people inside walls,” so they escape farther west and take a job in a mine in Utah, in a winter so severely cold that their underwear freezes like iron ice and their breath freezes like fire in their lungs.

The landscape is wild, the people they meet are wild, and “… now they had both become profoundly and ineradicably intimate with cold for the first time in their lives, a cold which left an ineffaceable and unforgettable mark somewhere on the spirit and memory … The cold in it was a dead cold. It was like aspic, almost solid to move through, the body reluctant as though, and with justice, more than to breathe, live, was too much to ask of it.” It’s elemental, and it has stripped them down till they’re raw and vulnerable, and seem to have only each other in the world. Which was what they wanted, but more than they bargained for. “Excuse me, mountains. Excuse me, snow. I think I’m going to freeze.”

[They end up in dry, hot, and dusty New Orleans. He botches her abortion, she dies, he goes to prison. Worth a re-read in this day and age. Though this is not about that.]

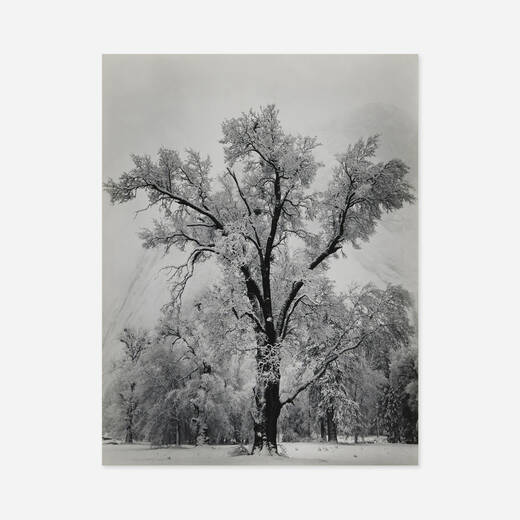

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about accounts I’ve read of storms in the Midwest back in the days of pioneers and homesteaders. The extreme cold of this landscape is also part of our mythology. I’ve read letters home from people making the journey out west — of blizzards that last for days and bury entire flocks of cattle, entire houses, and towns. Snow that makes its way into houses made of sod or held together with mud or dug into a hillside. They didn’t fear losing power, because they didn’t have it to begin with, and it must have been hard to keep their fire going and their wood dry for days and days on end. I think of The Long Winter, by Laura Ingalls Wilder. These books are a part of our mythology, too. Like all of our origin stories as a country, these are flawed and problematic at times, but they have a strange stark power to them as well.

I didn’t read the Little House on the Prairie books until I was an adult, but when I finally came to them they spoke to me in a strange way. I read them at an odd point in my life — I was far from home, by myself, feeling a little lost and lonely and down. Something about the simplicity of the tales appealed to me. The work of the characters was so hard and so endless and they faced it with such energy and thrift and cheerfulness. When they had nothing they found something to be thankful for, they found a way to make themselves what they needed. I love the straightforward yet disarmingly eloquent language and the detailed descriptions of everyday activities, so strangely fascinating to us now, though they must have seemed dreary and dull enough at the time. I thought of these books again during the pandemic, when we were all a bit stuck with the same people in the same place, making do. Making do is part of the American myth, too.

Like Faulkner’s Wild Palms, Ingalls’ books also capture the moodiness and mystery of some force that comes from nature that is bigger than anything we understand. As with Faulkner, the elements become almost a character in the narrative — a force that shapes lives. But, of course, in the series of books Ingalls wrote, the narrator is Laura, herself, recounting her childhood memories. She’s moved by all of the strange actually awesome ways that nature works. And she relates the story of them, she shares them with us, with a simplicity and rawness and unexpected poetry that might have gotten more attention if she’d been a man. I love Laura’s strange thoughts and the beautiful way that she expresses them. I love the fact that even at the time they found her strange. In an isolated world of stark strangeness, her odd poetry stood out, even to her family.

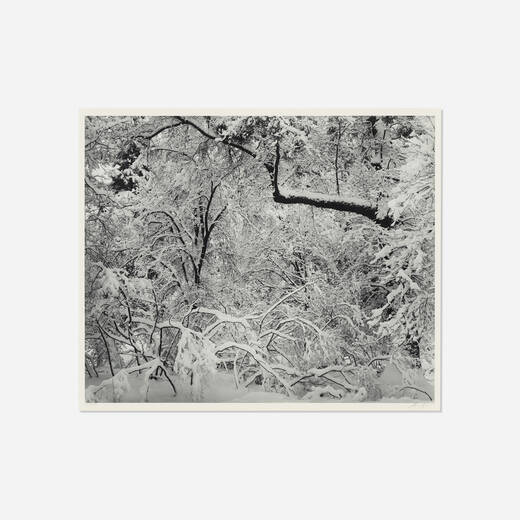

In one passage from The Long Winter, she recounts the surreal tale of a huge storm that buries them in snow and freezes the heads of an entire herd of cattle to the ground. When Laura relates the story to her mother and sister they find it so strange they think she invented it, ‘”It must be one of Laura’s queer notions,” Mary said, busily knitting in her chair by the stove. “How could cattle’s heads freeze to the ground, Laura? It’s really worrying, the way you talk sometimes.”‘

Outdoors the sun-glitter hurt her eyes. She breathed a deep breath of the tingling cold and squinted her eyes to look around her. The sky was hugely blue and all the land was blowing white. The straight, strong wind did not lift the snow, but drove it scudding across the prairie.

The cattle were standing in sunshine and shadow by the haystacks-red and brown and spotted cattle and one thin black one. They stood perfectly still, every head bowed down to the ground. The hairy rednecks and brown necks all stretched down from bony-gaunt shoulders to monstrous, swollen white heads.

“Pa!” Laura screamed. Pa motioned to her to stay where she was. He went on trudging, through the low-flying snow, toward those creatures.

They did not seem like real cattle. They stood so terribly still. In the whole herd there was not the least movement. Only their breathing sucked their hairy sides in between the rib bones and pushed them out again. Their hip bones and their shoulder bones stood up sharply. Their legs were braced out, stiff and still. And where their heads should be, swollen white lumps seemed fast to the ground under the blowing snow.

On Laura’s head the hair prickled up and a horror went down her backbone. Tears from the sun and the wind swelled out her staring eyes and ran cold on her cheeks. Pa went on slowly against the wind. He walked up to the herd. Not one of the cattle moved.

For a moment Pa stood looking. Then he stooped and quickly did something. Laura heard a bellow and a red steer’s back humped and jumped. The red steer ran staggering and bawling. It had an ordinary head with eyes and nose and open mouth bawling out steam on the wind.

Another one bellowed and ran a short, staggering run. Then another. Pa was doing the same thing to them all, one by one. Their bawling rose up to the cold sky. At last they all drifted away together. They went silently now in the knee-deep spray of blowing snow.

Laura is spooked by the experience, “She was not able to tell Ma and Mary what she felt. She felt that somehow, in the wild night and storm, the still-ness that was underneath all sounds on the prairie had seized the cattle.” Laura is bewildered by the mystery of the world around them, but to others, the relationship to the cold is one of conflict. The freezing weather is a character in the story, it is an enemy to be overcome. And Laura’s father is the same way, he hears the strange voices of the elements, too, and he sees the signs. He sees the challenges of survival as a darkness, and he works hard to keep the darkness away from his family. Pa rose with a deep breath. “Well, here it is again.” Then suddenly he shook his clenched fist at the northwest. “Howl! blast you! howl!” he shouted. “We’re all here safe! You can’t get at us! You’ve tried all winter but we’ll beat you yet! We’ll be right here when spring comes!”

Laura’s future husband Almanzo also sees the world around them and the elements as almost living things:

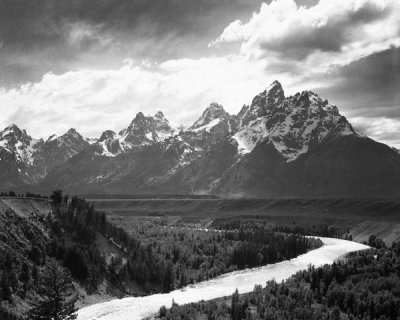

“But he had a feeling colder than the wind. He felt that he was the only life on the cold earth under the cold sky; he and his horse alone in an enormous coldness.

“Hi-yup, Prince!” he said, but the wind carried away the sound in the ceaseless rush of its blowing. Then he was afraid of being afraid. He said to himself, “There’s nothing to be afraid of.” He thought, “I won’t turn back now. I’ll turn back from the top of that next slope,” and he tightened the reins ever so little to hold the rhythm of Prince’s galloping.

From the top of that slope he saw a low edge of cloud on the northwestern sky line. Then suddenly the whole great prairie seemed to be a trap that that knew it had caught him.”

In my mind, perhaps the elements and the land feel so hostile to the Ingalls because they weren’t supposed to be there in the first place. Over the course of the series, the Ingalls are living out the promise of manifest destiny — the idea that white Christians were chosen by their god to spread their religion and their morality across the country. They believed that they had some sort of claim to the land regardless of who lived there when they arrived. Laura is confused by this, though her parents accept it as given.

“Oh I suppose she went west,” Ma answered. “That’s what Indians do.”

“Why do they do that, Ma?” Laura asked. “Why do they go west?”

“They have to,” Ma said.

“Why do they have to?”

“The government makes them, Laura,” said Pa. “Now go to sleep.”

…

“Will the government make these Indians go west?”

“Yes,” Pa said. “When white settlers come into a country, the Indians have to move on. The government is going to move these Indians farther west, any time now. That’s why we’re here, Laura. White people are going to settle all this country, and we get the best land because we got get here first and take our pick. Now do you understand?”

“Yes, Pa,” Laura said. “But, Pa, I thought this was Indian Territory. Won’t it make the Indians mad to have to—–”

“No more questions, Laura,” Pa said, firmly. “Go to sleep.””

When you approach the land that you want to build a home on as something to be conquered and overcome rather than something to understand and appreciate, it only makes sense that it will reject you on some natural and spiritual level. When you remove or raze the wildlife, ruin the balance of nature, destroy or shut out the beauty and the speaking voice of the trees and the sky, even of the cold and the snow, you might feel that the spirits are speaking cruelly to you. For many settlers, though they needed to adapt, they were bringing methods of farming and building homes from a different environment and trying to conform the land to their needs, their customs, and their expectations. They were expecting their god to provide for them, and to preserve them, and to herald them as they drove further and further west claiming everything as their own by right. But perhaps they weren’t listening to the voice but, rather trying to block it out.

The parallel story in Wild Palms, The Old Man tells a tale of the flooded Mississippi — a flood of biblical proportions. As Faulkner describes it, with convicts traveling the road in a truck, watching the strange movement of the water, it has a strong sense of The Man doing something, and nature overwhelming that decision with its own bewildering power. Things don’t go well. Most religions have a story of a flood. We hear what we want to hear, but as the waters rise and the earth gets warmer and we are slowly killing it, perhaps we need to hear a different message from nature or from our god, however we think of god. Maybe the message has been there all along, but we heard it wrong.

Categories: featured