“Why are you acting like such a fool?”

I nod my head and don’t answer.

I could say something, but why?

Do you want to know what’s in my heart?

From the beginning of time: just this! just this!

Taigu Ryōkan (probably) compiled a list of “Admonitory Words,” and they were likely addressed to himself. The list mainly concerns words themselves and ways they are used that he hoped to avoid, such as talking too much, too fast, too boastingly, too pedantically, repeating oneself, or making glib promises. One thing he sought to avoid was trying to explain something to others that you don’t understand yourself. If I were to heed this advice, I would not write about Taigu Ryōkan, whom I can never hope to understand. And yet here I go.

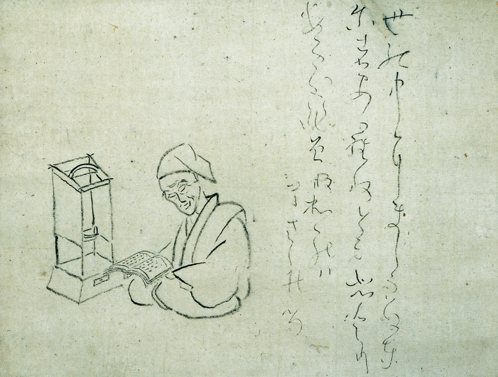

I will not try to explain him, because that cannot be done. I will, instead, talk about him as someone who feels like a kindling spirit to me. I will talk about his beautiful words and calligraphy and the many stories of his life, that shift as quickly and as often as huge contented fish in an ancient pond or long sunbeans in deep woods.

Taigu Ryōkan was (probably) born in 1758 — the same year as Mozart, (and judging from Mozart’s wonderful letters, I see a connection in their childish whimsy and sweetness). He was the oldest son of a village headman, who was a prosperous merchant, well-known haiku poet, and Shinto priest.

Of his youth, Ryōkan wrote, “When I was a lad,/ I sauntered about town as a gay blade, / Sporting a cloak of the softest down,/ And mounted on a splendid chestnut-colored horse./ During the day, I galloped to the city; / At night, I got drunk on peach blossoms by the river./ I never cared about returning home,/ Usually ending up, with a big smile on my face,/ at a pleasure pavilion!” But he had some sort of spiritual change, and rather than taking over his father’s place as a village headman and accepting a life of business and wealth, he shaved his head, renounced the world, and became a Buddhist monk. He became the disciple of a Zen priest called Kokusen at the age of 22, and studied under him for over a decade.

He learned calligraphy and different types of poetry, in Chinese and Japanese. When Kokusen died, Ryōkan set out on a pilgrimage for a few years, and in 1804 he made himself a home in a hut on Mt. Kugami.

“It is not that I do not wish to associate with men,

But living alone I have the better Way.”

Instead of establishing his own temple or preaching, he lived as a mendicant, wandering to the villages near his home and asking for just enough food to survive. He wrote poetry, practiced calligraphy, and lost himself in the beauty of the moon. He spent his days playing with children or drinking sake with woodsmen and farmers. Though he lived a life of austerity, he enjoyed drinking wine and talking about poetry and life, long into the night. Legendarily, on one trip to the tavern to buy sake to share with a friend he disappeared and was found hours later, leaning against a tree, lost in the sublime beauty of the moon. “Stretched out,/ Tipsy,/ Under the vast sky:/ Splendid dreams/ Beneath the cherry blossoms.” And as much as he distrusted words and the way we use them, he spent hours and hours in his hut putting them together as beautiful poetry and practicing calligraphy. He still created.

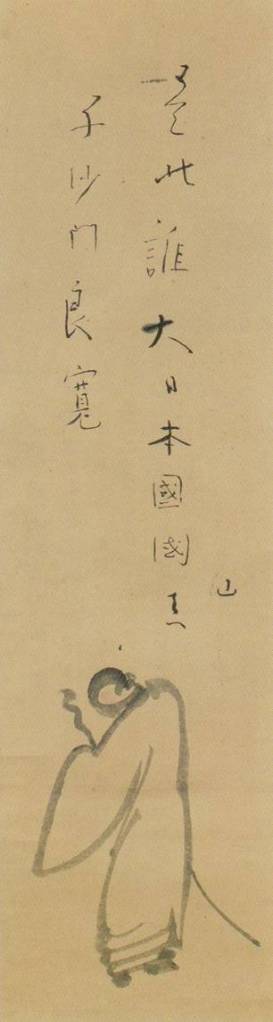

He spent his days walking for miles from village to village and playing games with the children there, who were always happy to see him. He did not consider himself to be a saint or a teacher. “Too lazy to be ambitious,/ I let the world take care of itself./ Ten days’ worth of rice in my bag;/ a bundle of twigs by the fireplace./ Why chatter about delusion and enlightenment?/ Listening to the night rain on my roof,/ I sit comfortably, with both legs stretched out.” And though he wrote many different kinds of poetry, some very formal, some free-style and almost narrative, he did not consider himself a poet, “Who says my poems are poems?/ These poems are not poems./ When you can understand this,/ then we can begin to speak of poetry.” He saw no value in fame, he needed no recognition, and he had no worry for his legacy. “My legacy –/ What will it be?/ Flowers in spring,/ The cuckoo in summer,/ And the crimson maples/ Of autumn…“

When he became too ill to live alone, he moved in with a patron where he fell in some kind of love with Teishin, the young nun who took care of him. Apparently from the moment they first met they were delighted with each other’s company, and they wrote a series of poetry back and forth to each other. In one called Teishin, he says, “’When, when?’ I sighed./ The one I longed for/ Has finally come;/ With her now,/ I have all that I need.” She was with him when he died, sitting up, as if falling asleep. On his death bed, he gave her this poem, “Now it reveals its hidden side/ and now the other—thus it falls,/ an autumn leaf.”

There are a million stories about Taigu Ryōkan, and they have shifting significance for the people who tell them. People find different meanings in his words and his silence, his action or lack of action. We find the meaning we need to find in the stories of his life.

Most stories of Taigu Ryōkan change in the details wherever you find them, but the substance of them is the same, and they reveal a portrait of a man who was generous and kind to all things and all people. He greeted everyone pleasantly with a smile, and bowed to anyone who labored. “In the morning, bowing to all;/ In the evening, bowing to all./ Respecting others is my only duty–” He supposedly set lice inside his clothes to keep them warm in winter, and always left a leg bare to feed the mosquitoes in summer. He cut a hole in the floor of his hut to allow a bamboo shoot to grow, and may have burnt his hut down trying to make a hole in the roof for it when it grew larger. Famously, when a thief tried to rob him he regretted that he had nothing to steal. He gave the thief his clothes, and then sat naked staring at the moon, wishing he could have given it, or at least the beauty of it, to the thief. “The thief left it behind:/ the moon/ at my window.“

Although he never proselytized, the stories tell that he changed people just by being with them. When he stayed somewhere as a guest, although he never spoke to his hosts about how they should live or believe or conduct themselves, wherever he stayed people felt happier and more peaceful, the household more harmonious. The house smelled pleasant and felt peaceful for some time after he left.

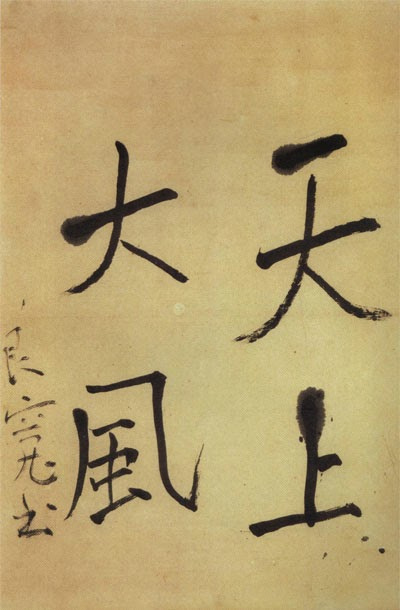

Taigu, a name he gave himself, means “great fool.” The word “fool” has meant many things over the centuries, but for Ryōkan, it seems as though being a fool gave him freedom from everything. A fundamental, simple, profound freedom. And somehow, unfettered and untethered, aside from it all, he discovered something I certainly have no words for, though he did. A freedom from relating everything he experienced to his own state of being, a freedom from even thinking about himself long enough to wonder if he had achieved enlightenment. Depth, weightlessness, peace, understanding, utter lack of understanding, essential humanity, a reflection on the complete absurdity and inconsequentiality of humanity.

We are nothing compared to the changing of the seasons, the working of nature, the animals, the elements. We can’t explain it and don’t need to understand it or even try. “The winds have died, but flowers go on falling;/ birds call, but silence penetrates each song./ The Mystery! Unknowable, unlearnable./ The virtue of Kannon” We don’t need to think about ourselves. We do not need many things.

You Do Not Need Many Things

My house is buried in the deepest recess of the forest

Every year, ivy vines grow longer than the year before.

Undisturbed by the affairs of the world I live at ease,

Woodmen’s singing rarely reaching me through the trees.

While the sun stays in the sky, I mend my torn clothes

And facing the moon, I read holy texts aloud to myself.

Let me drop a word of advice for believers of my faith.

To enjoy life’s immensity, you do not need many things.

Yes, I’m Truly A Dunce

Yes, I’m truly a dunce

Living among trees and plants.

Please don’t question me about illusion and enlightenment —

This old fellow just likes to smile to himself.

I wade across streams with bony legs,

And carry a bag about in fine spring weather.

That’s my life,

And the world owes me nothing.

At Master Do’s Country House

Two miles from town, I meet an old woodcutter

and we travel the road lined with huge pines.

The smell of wild plum blossoms

drifts across the valley.

My walking stick has brought us home.

In the ancient pond – huge, contented fish.

Long sunbeams penetrate the deep woods.

And in the house – a long bed

all covered with poetry books.

I loosen my belt and robes,

copy phrase after phrase for my poems.

At twilight, I walk to the east wing –

spring quail startle into the air.

Tramping for miles I come upon a farm house

as the great ball of sun sets in the forest.

Sparrows gather near a bamboo thicket,

flutter about in the closing dark.

From across a field comes a farmer

who calls a greeting from afar.

He tells his wife to strain their cloudy wine

and treats me to his garden’s feast.

Sitting across table we drink each other’s health

our talk rising to the heavens.

Both of us are so tipsy and happy

we forget the rules of this world.

Too confused to ever earn a living

I’ve learned to let things have their way.

With only three handfuls of rice in my bag

and a few branches by my fireside

I pursue neither right or wrong

and forget worldly fortune and fame.

This damp night under a grassy roof

I stretch out my legs without regrets.

No Mind

With no mind, flowers lure the

butterfly;

With no mind, the butterfly visits

the blossoms.

Yet when flowers bloom, the butterfly

comes;

When the butterfly comes, the

flowers bloom.

Dreams

in this dream world

we doze

and talk of dreams —

dream, dream on,

as much as you wish

First Days Of Spring – The sky

First days of Spring-the sky

is bright blue, the sun huge and warm.

Everything’s turning green.

Carrying my monk’s bowl, I walk to the village

to beg for my daily meal.

The children spot me at the temple gate

and happily crowd around,

dragging to my arms till I stop.

I put my bowl on a white rock,

hang my bag on a branch.

First we braid grasses and play tug-of-war,

then we take turns singing and keeping a kick-ball in the air:

I kick the ball and they sing, they kick and I sing.

Time is forgotten, the hours fly.

People passing by point at me and laugh:

“Why are you acting like such a fool?”

I nod my head and don’t answer.

I could say something, but why?

Do you want to know what’s in my heart?

From the beginning of time: just this! just this!

In My Youth I Put Aside My Studies

In my youth I put aside my studies

And I aspired to be a saint.

Living austerely as a mendicant monk,

I wandered here and there for many springs.

Finally I returned home to settle under a craggy peak.

I live peacefully in a grass hut,

Listening to the birds for music.

Clouds are my best neighbors.

Below a pure spring where I refresh body and mind;

Above, towering pines and oaks that provide shade and brushwood.

Free, so free, day after day —

I never want to leave!

Reply To A Friend

In stubborn stupidity, I live on alone

befriended by trees and herbs.

Too lazy to learn right from wrong,

I laugh at myself, ignoring others.

Lifting my bony shanks, I cross the stream,

a sack in my hand, blessed by spring weather.

Living thus, I want for nothing,

at peace with all the world.

Your finger points to the moon,

but the finger is blind until the moon appears.

What connection has moon and finger?

Are they separate objects or bound?

This is a question for beginners

wrapped in seas of ignorance.

Yet one who looks beyond metaphor

knows there is no finger; there is no moon.

Returning To My Native Village

Returning to my native village after many years’ absence:

I put up at a country inn and listen to the rain.

One robe, one bowl is all I have.

I light incense and strain to sit in meditation;

All night a steady drizzle outside the dark window —

Inside, poignant memories of these long years of pilgrimage.

At Dusk

at dusk

i often climb

to the peak of kugami.

deer bellow,

their voices

soaked up by

piles of maple leaves

lying undisturbed at

the foot of the mountain.

Blending With The Wind

Blending with the wind,

Snow falls;

Blending with the snow,

The wind blows.

By the hearth

I stretch out my legs,

Idling my time away

Confined in this hut.

Counting the days,

I find that February, too,

Has come and gone

Like a dream.

Midsummer

Midsummer —

I walk about with my staff.

Old farmers spot me

And call me over for a drink.

We sit in the fields

using leaves for plates.

Pleasantly drunk and so happy

I drift off peacefully

Sprawled out on a paddy bank.

When All Thoughts

When all thoughts

Are exhausted

I slip into the woods

And gather

A pile of shepherd’s purse.

Categories: featured, literature, Nature, poetry, why I love