Godard filmed Masculin Féminin without a script. Rather, he worked from a notebook full of snippets of dialogue, flashes of inspiration, notes and sketches he’d written the night before shooting. The resulting film is structured and chaotic, uneventful and action-packed, random but wonderfully cohesive. It’s teeming with questions — profound and ridiculous — and with thoughtful disarming vague half-answers. And underneath all the words and ideas the film is very human, capturing our foibles, our nonsense, our violence, and our tenderness. I’ve been thinking about Masculin Féminin so much lately. So much of our lives in America today reminds me of this oddly prescient film, made in Paris over half a century ago.

Masculin Féminin is a film about the culture of youth, the sincere, foolish, self-absorbed search for meaning and identity. Godard, who was thirty-five when the film was shot, approaches the subject as an outsider, a documentarian, at once fascinated, amused, and dismayed by all that he sees. The film shows a clash between passionate revolutionary spirit, actual world events, day-to-day realities, and celebrity pop culture. The characters are famously described as the children of Marx and Coca-Cola. The dialogue is a manic combination of poetry, pop songs, and advertising slogans.

The world is full of violence. From the first scene, everywhere the kids go random strangers around them are shot or stabbed, or stab themselves. One stranger borrows a match from Paul and uses it to set himself on fire to protest the war in Vietnam. And I doubt 1960s Paris was a cauldron of constant violence, but if you read the news it often feels as though 21st-century America is. The intertitles shoot onto the screen with the sound of gunshots, the very words are violent and powerful. And the film is full of words, and the words are muddled and beautiful.

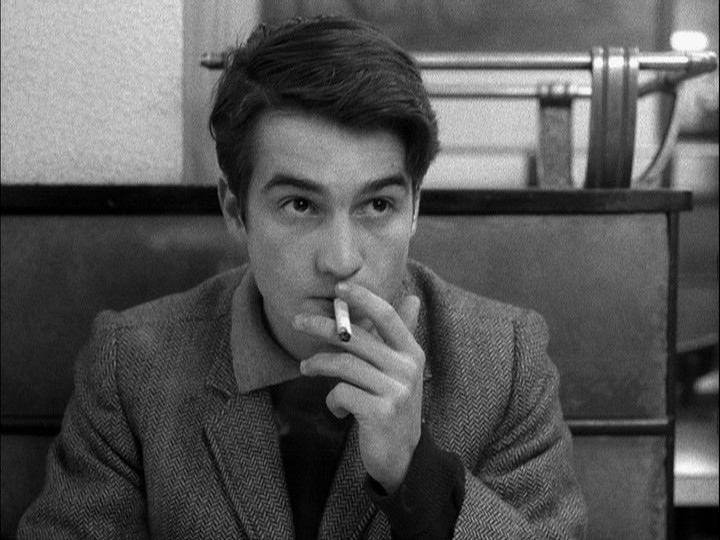

The film tells the story of Paul, a moody would-be philosopher just out of the army, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, and Madeleine, a model who wants to be a singer, played by model-turned-singer Chantal Goya. Godard questioned and reexamined many things in his films, including the way we make films, the way we watch films, the very way we see. He revolutionized filmmaking forever. But one aspect of traditional cinema he seemed pretty happy with was putting beautiful women on the screen. Many of the women in Masculin Féminin are gorgeous and fairly stupid, as Godard demonstrates in one uncomfortable interview after another. Of course, this is Godard, so it’s impossible to say if he sees the girls in a certain way, if he’s showing us that we do, or if it’s all the point of view of his conflicted and lovelorn hero. Perhaps they’re just young, just a product of their culture. And he includes scenes in which Madeleine asks the questions, from off-screen, and Paul is the subject of the unrelenting gaze of the camera, which is oddly touching and affecting, and makes them both seem more vulnerable and human.

Paul is searching for some way to understand the world and his place in it, some way to describe it that he can hold onto, but he realizes as he speaks that this isn’t possible. Paul gets a job as a pollster for the Institut francais d’opinon publique, and in a series of beautiful scenes he wanders the streets of Paris as night falls, with the questions on his surveys playing in his head. His voiceover becomes a litany about the times. About his time and our time, and about time passing. The world is changing as he watches, he himself changes every moment, and though he’s an insufferably pretentious poser at times, there’s something endearing about his struggle. He decides that to be honest is to act as though time didn’t exist. And it’s strangely discombobulating to hear him say this in the context of a movie about youth and time passing, to think about Léaud, the actor, as we’ve seen him grow and age on film, from the child in 400 blows, through scores of films with most of the notable directors in the history of film. It’s strange to think about how little our world has changed — we’re still at war, we still reward shallowness over talent, and we’re still constantly bombarded by a world for sale.

Amidst all the chaos of words and gunshots and advertising jingles, Godard shows us quiet moments of connection and poetry, fleeting but hopeful. Godard has created an eccentric messy portrait of the world around him, it’s complicated, discouraging and ambiguous, but in capturing it he has made it beautiful.

I loved this film. Very important to me growing up. Leaud, in this one and Stolen Kisses, was the ultimate of vulnerable/cool.

LikeLike

Something about seeing him in 400 blows makes me care and worry about him differently.

LikeLike