(Blow Up My Town, Chantal Akerman, Belgium, 1968)

By Adrian Martin

November 1968. At the age of 18, Chantal Akerman made Saute ma ville in her hometown of Brussels, just for herself, for the fun of it. The previous year, she had entered INSAS film school and dropped out within three months. There is a photo of her on the shoot in her 2004 book Autoportrait en cinéaste (“self-portrait as a filmmaker”), standing on the terrace that remains off-screen in the film itself, outside the small kitchen that provides the only location.

She made it, then she went to Paris; the single reel sat in a Belgian laboratory for two years (as Philippe Garrel’s L’Enfant secret did in a French lab a decade later), because she couldn’t afford to pay the bill to claim it. It was only in 1970, when Eric de Kuyper (who became her lifelong friend and collaborator) wished to screen it on his TV show devoted to experimental cinema, that Saute ma ville left its solitary confinement.

A kitchen so small it really allows only two angles, from one end facing the door, and the counter-angle from the other end. (Walking into the camera and blacking out the frame expedites the cuts between angles.) There’s clearly something about Belgian kitchens, or at least the ones that Akerman gravitates to: this one in Saute ma ville, Delphine Seyrig’s in Jeanne Dielman(1975), and her own mother’s in her final film No Home Movie (2015) all look uncannily the same, especially tile-wise, and in their claustrophobic shape. “Domestic space”, as Akerman jokes in Autoportrait, is her specialty.

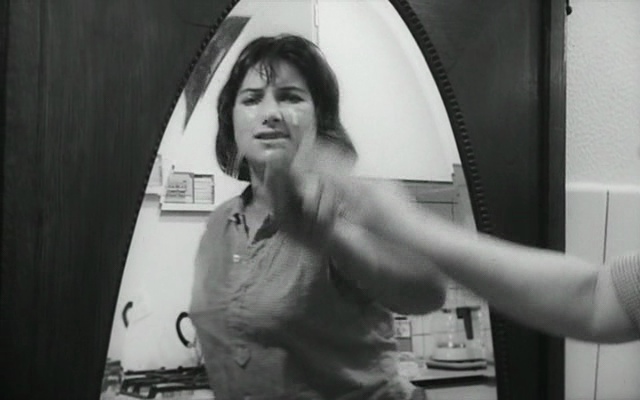

In her debut, Akerman bursts forth both (as it were) behind and before the camera. It’s a récit, a tale, as a starkly printed word on-screen announces. After a brief street intro reminiscent of many a Nouvelle Vague film (and a dedication “pour Claire”) followed by a frantic contest pitting stairs against elevator, Akerman enters this little kitchen through its door, and seemingly locks it. Then the kitchen immediately becomes a whole world. A world of performance-art-style actions and activities – a field that Tsai Ming-liang will later mine extensively in his films.

Across 12-and-a-half minutes, she cooks, she eats, she mops the floor, she shines her shoes. A cat gets thrown into the frame, and is then thrown out of it. Chantal assiduously covers over the air-gaps along the door, effectively walling herself in like Walerian Borowczyk’s Blanche – but without any patriarchs of Church or State wielding the tape.

Eventually, there’s some Dionysiac dancing with spilt milk. Maybe she looks for a job in the newspaper ad section, then abandons the idea; who knows? Then she starts popping balloons, lighting things on fire, and setting the gas of the oven going as well. Boom, it’s suddenly all over: the woman, her space, her town, the world. Why not?

Eating spaghetti alone in one’s kitchen, as Akerman also notes in Autoportrait, is both a funny and a sad image to contemplate. Ordinary, everyday, “flat” as she loves to say. But here the action swiftly turns toward the chaotic, the burlesque. Jonas Mekas called it her “Chaplin film”. Akerman always declared her natural clumsiness, her maladaptation to daily life (I saw this in action myself at several film festivals – embracing her clumsiness was her way of having an evident, un-negatable place in the world). Here, it becomes the substance of gags: throwing everything onto the floor, including a bucket’s worth of water, before cleaning it; using the polish to blacken not only her shoes but her legs, in a continuation of the gesture.

To clean a mirror (alert: major Akermanian motif) just as a way to dirty and fog it up more. This crazy work-around logic of the domestic space will re-emerge in the splendid The Man with the Suitcase (1983), also starring Akerman.

“Saute ma ville was already a response to Jeanne Dielman”, she said – before its time, in reverse causality. No alienation, only comedy and play. Anarchy: even the idea of suicide is a joke. We critics love to retrospectively grab onto the first works of great directors and demonstrate that “everything was there”, in embryo or even well-developed, already. That means we have to acknowledge the fact that even her death is foretold there. You gotta laugh. “In Saute ma ville, Chantal laughs at everything”, remarks one of her fetish-actors, Sylvie Testud. “Even her own disappearance”.

“There are several ways to make explosives. What does the job here relies on the principle of compression – within a too strict, too rigid space – of an accumulation of unstable elements, to the point where over-fullness makes everything violently explode. It’s 1968, right?” – Jean-Michel Frodon, on one of his better days. He suggests that the film previews that materiality of Akerman’s cinema which “forms symptoms, perhaps signs – but of what?” Of what, indeed?

Answers will always be forthcoming on that question. In March 2020, prime pandemic, Saute ma ville is taken by Matt McKinzie on the site Pop Matters as an allegorical example of “the art of social distancing”, a film “directly reflecting our current state, serving as a meditative text on the art of staying at home”. Whatever. “Perhaps we’re going mad”, he writes. “Perhaps we’re reclaiming a limited space and transforming it by our own will”. But the dreamy (or scholarly) equivocation of perhaps is not the mode of Saute ma ville. It’s a brute, mad, childlike reality.

Tellingly, the soundtrack didn’t get heard by that pop-mattering champion. The aurality is wild: it’s Akerman watching the reel play through and accompanying it with what Raúl Ruiz called “mouth music”, which is what he produced from his body when he did something very similar to fill the absent soundtrack of his re-found debut short, La maleta (1963), in 2008.

With Akerman, it’s more on the register of singing than murmuring, but all bases are covered: humming, manic “dramatic” music, out-of-sync Foley effects (“scratch” for match-lighting, “bang bang” for balloon-bursting), nutty “mickey-mousing”. And a few big holes of stark silence, too, no “atmos” track. A kind of dream of what a movie soundtrack should be, playing in her head and expelled through her vocal chords. Pure amateur cinema.

The voice is there, over black, before the images start, and it stays on past the end (the looped explosion sound) to read out the few technical credits (including editor Geneviève Luciani with whom she would work until 1974) – just like Orson Welles used to do in the early 1940s. And she sings a bit more, too.

May ’68, March ’20? Forget about the symptoms, the signs and the allegories. Mop your floor, eat your spaghetti, blow up your town.

Adrian Martin is an Australian film and arts critic. He now lives in Malgrat de Mar in Spain. His work has appeared in many magazines, journals, and newspapers around the world, and has been translated into over twenty languages See more of his work on his site Film Critic: Adrian Martin. To fund the ongoing existence and updating of his wonderful website, support it through Patreon.